Conceptions, Methods, Techniques and

advertisement

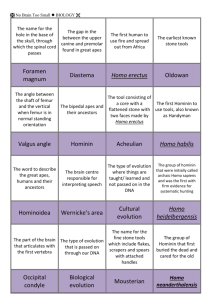

Conception.doc Über Prof.Dr. G.D. Neuhäuser, Dresdener Str.24, 35440 Linden Leihgestern email: gdneuhaeuser @ gmx.de Sehr geehrter Herr Neuhäuser, Conceptions, Methods, Techniques and Traditions in the Early Palaeolithic An Old World’s view on human’s being and human’s early history Lutz Fiedler It will not be discussed again tool using, tool connected insights and strategies of animals in this paper. Behaviour of animal and human has the same basis and can not be divided clearly at this point (Corbey 2005). This is the case if we look at the earliest artefacts from Koobi Fora at Lake Turkana in East Africa (2.5 to 2.6 my years old). Most of them are smashed and battered stone fragments only characterized by more or less useful cutting edges (Bunn, Harris, Isaak et. al. 1980). But technology developed from that period of Koobi, what can be seen in the Early Oldowan tool kit: Artefacts were generally produced by a well defined flaking technology (Leakey 1971). The knowledge of this early technology spread from South Africa over East and Northwest Africa (Sahnouni 1998 a – b) to Southern Europe (Roe 1995) and Asia (Gabunia et. al. 1999). What was the reason for this wide distribution? Had man virtually some kind of instinct for a special way of stone working at that time, or was it more? Stone tools were not produced because man had the ability for appropriate striking techniques. Tools were produced with the clear intention to use them for foreseeable approches. In this way they belong to the social conception of live. This means, that all members of early human groups know what tools are, how they were manufactured, how they have to look and for what reason they have to be produced. This means tradition in a communicative system. Tool production, tool use, and tool necessity were stored in memory as »pictures in the brain«. These abstract, “neuronal” images could than be realised virtually in all similar situations of live (Fiedler 1993, 1997, 2002 a-b). It is not possible to state that vocal language is essential to continue such a tradition. But thinking and acting in logical lines or steps toward a defined goal is the basis for the grammatical structure of language (Fiedler 1993). Words can be compared with tools. Pretty much like words tools are classified for special reasons. Desired results of work can be managed only with the right tools in a correct, logical order of use. So work has a special, object connected grammar (Wittgenstein 1953). To understand a process of work means to understand what I do as well as to understand what another person does while working. This is a way of self-awareness (or self perception) and it is the basis for communication, too. Oldowan tools are classified into several functional types: cutting tools, scrapers, chopping tools, drills, anvils, and hammer stones (Leakey 1971, Leakey & Roe 1994). The archaeologist’s typological classification, based on morphology, contains hammer-stones, simple cores, diskoide cores, polyhedrons, spheroids, flakes, denticulates, notched pieces, borers/drills, unifacial worked choppers, bifacial worked chopping tools, chisel like punches, proto-bifaces, and pitted anvils. All these tools are related to special tasks. Most of them are to be seen in a wider range of such activities: A hammer stone serves to produce flakes, a flake is the blank for a denticulate, a denticulate serves as a scraper for wood working, a wooden digging stick is necessary for the group’s supplements and subsistence. Under these the various Oldowan too types and their relations are representing variable resp. structured working processes and they speak for a social pattern emerging in human groups, relying on communication about effort, time as well as participation. This is different from most tool using seen in animal behaviour. It is a special human system of life, and it could be called protocultural. The Oldowan stage of culture ended about 1.8 my years ago. In Bed II of the Olduvai Gorge geological sequence it changed its character toward the Lower Acheulian (or Early Acheulian; Leakey 1971, Leakey & Roe 1994, Stiles & Patridge 1997). Most of the Acheulian tools have a much stronger defined shape, especially the cleavers, hand axes (bifaces), picks, and knifes (Clark 1970). So it is possible to say that the abstract, held in mind tool models were more complex than in Oldowan times (Fiedler 1998 a-b, 2002). A handaxe, for example, was not easy to realize. The producer (or another member of his group) of such a tool had to look out for the appropriate raw material. He had to know where in the home range it could be found. He also had to look for good hammer stones and for bones or ivory as ‘soft’ hammers. His first work was to split off a heavy flake (much more than 20 cm in diameter) as a blank for the final handaxe. Prepared flakes without the former cortex of the rock are better than simple cortex flakes. Thus, preparation normally starts before flaking off the blank (fig. 1 -2). The experienced person who strikes off such a flake has to have a lot of control over his work. This requires mastering of several components: the hammer stone’s weight, the strength of the blow, the point where the hammer stone should hit the block of rock, the angle of the striking direction, and the underground on which the struck off flake falls down. Working out a handaxe on a flake blank starts with heavy blows along its edge. In this way the planned handaxe gets its first rough shape. Then the blank has to be turned to its backside and must be flaked in the same manner. The rough out now has a crude ovate contour. After correcting the shape with several other blows the kind of hammer must be changed. A smaller one or a so called soft hammer of ivory or bone is necessary. From now on the producer has to split off a series of flat and thin flakes to form both, a sharp cutting edge around the contour and flat surfaces on both sides of the tool (Fiedler 2007). After completion the handaxe has an elongated ovate shape and more or less two straight cutting edges down from the tip to the basis. Such a handaxe serves for butcher carcasses of large game like elephants, rhinos or hippos. It can also be used for wood working, carving, scraping and cutting. On the African Plains, where raw material for stone tool production was rare, hand axes carried by the hunters also have served as cores for the exploitation of light duty flakes (Fiedler 2002 a). Millions of such elaborated Acheulian hand axes have been found in Africa, Asia and Europe until now. The question is, why all that labour-intensive work for a simple cutting tool? A simple, heavy sharp flake could certainly have fulfilled nearly all the requirements of such a handaxe! The reason for this must be cultural tradition. Some of the»pictures in the brain« have developed more and more to determine imperative symbols: A butchering tool for big game has to look like a real handaxe. In this way it was manufactured by fathers, grandfathers, and all the – mythological – ancestors. In doing so, the world could be held in an important balance. Another cultural reason is identity, because every person who is able to fulfil the traditional tasks is a good and appropriate member of the society. It is necessary for each individual to belong to his human group and it is forced to do things in the right way. These facts and not technological abilities of the early humans can explain more than one million years of the Acheulian culture. Technological changes and innovations are seen as dangerous for man and world. An imperative cultural pressure and feeling of safety were in balance throughout longest period of human’s being (Fiedler 2002 a). Progress came slowly and appeared only quiet (Clark 1991, 1999). What was valid for hand axes can be applied to cleavers, wooden spears, fire places, huts, hunting methods, and the social organization. All the different archaeological findings from the Acheulian period bear witness of an extremely slow development. Changes came late, about 400.000 years ago, when the Levallois technique become in use in the world of the Upper Acheulian. From than on - in the Middle Palaeolithic innovations happened to be faster and faster until to the beginning of the Upper Palaeolithic, 40.000 years ago (Fiedler 2009). The coherence of Lower Palaeolithic groups based on two facts: their biological relationship and their techno-social environment. This environment represents an important system in some distance to nature, and by using systematic approaches it allows to ‘instrumentalize’ the world around or to organize some control about resources, i. e. exploitation of raw material, game, fire etc. In addition it has an important impact on the group’s behaviour. What does this mean for understanding early human being, particularly in regard to cognition, intelligence, communication, planning, and comprehension of existence? A well functioning techno-social system like the Acheulian have to be stored in mind by all members of the society by means of a huge amount of connected details. These details are specific elements of all the indivisible system: home range, animals, plants, resources, dangers, hunting, social range, social behaviour, tool types, tool manufacturing, tool use, fire, food preparation, food sharing, dwelling construction, preparing of hide, clothing, transport, and so on. There are many objects and a lot of functions or actions, to keep in mind as neuronal pictures and abstract scenarios. Everybody has to have very similar, comparable images of these affairs, related to the system’s function (Cassirer 1944). So it has to be communicated. The amount of Acheulian images and their network can not be communicated without gestures, vocals, symbols, language. Imaginated and abstract objects or situations (like mountains, rivers, bushes or stones for example) as well as functions (like hunting, gathering, sharing, manufacturing for examples) are put above all real possibilities of their virtual appearances. This gives man the distance necessary for thinking and talking about affaires, and for planning. In the Acheulian system the abstract and symbolic tool types, methods of manufacturing, and aims of tool production could be realised as virtual objects and actions. In analogy to this all other abstract phenomena had their counterpart in reality. Vocal symbols between abstraction and reality should have existed as spoken language, too. In this way the Acheulian system was realised and represented permanently by every individual and in the whole community. Therefore, we cannot state that abstract or symbolic representation and the realisation of symbols are characteristics of anatomical modern man only. It is a characteristic ability of man since his first appearance two million years ago. Some archaeologists hesitate to call the Acheulian a culture. They prefer to call it a techno-complex, because of its neutrality. This means that the term culture in relation to Palaeolithic findings is a doubtful one in science, culture seem to be a phenomenon of recent societies, especially the own one. But the scientific view on artefacts is a view on technology, forms and styles, what means a view on conceptions and knowledge of ancient societies. Conceptions, methods, techniques, symbol supported knowledge, communication, and tradition together are what we call culture (Cassirer 1944). References: Bunn, H., J. Harris, G. Isaak et. al. 1980: Fx Jj 50: An Early Pleistocene Site in Northern Kenya. World Archeology 12/2, 109-136. Cassirer, E. (1944): An Essay on Man - An Introduction to a Philosophy of Human Culture, New Haven. Yale University Press 1972. Cassirer, E. (1944): Versuch über den Menschen. Einführung in eine Philosophie der Kultur. Aus dem Engl. übers. von R. Kaiser, Hamburg 1996. Clark, J.D. 1970: The Prehistory of Africa. London. Clark, J.D. 1991: Stone artifact assemblages from Swartkrans, Transvaal, South Afrika. In: J.D. Clark (Hrsg.), Cultural beginnings. Approaches to understanding early hominid life-ways in the African savanna. RGZM Monographien 19, 137-158. Clark, J. Desmond 1999: Cultural Continuity and Change in Hominid Behaviour in Africa During the Middle to Upper Pleistocene Transition. In: H. Ullrich (Hrsg.), Hominid Evolution. Lifestyles and survival strategies. Gelsenkirchen/Schwelm, 277292. Corbey, R. 2005: The Metaphysis of Apes. Negotiating the Animal-Human Boundary. New York. Fiedler, L. 1993: Zur Konzeption des Altpaläolithikums. Technik, Planung und Sprache im System der Kultur. Ethnogr.-Archäolog. Zeitschrift 34, 1993: 1-15. Fiedler, L. 1997: Die materiellen Zeugnisse des Altpaläolithikums und ihre kulturelle Interpretation. In: L. Fiedler (Hrsg.) 1997: Archäologie der ältesten Kultur Deutschlands. Ein Sammelwerk zum älteren Paläolithikum, der Zeit des Homo erectus und des frühen Neandertalers. Materialien zur Vor- u. Frühgeschichte von Hessen 18, 364-367. Fiedler, L. 1998 a: Conception of Lower Acheulian tools. In: E. Carbonell, J.M. Bermúdez de Castro, J.L. Arsuaga & X.P. Roddriguez 1998 (edts.): The First Europeans: Recent discoveries and current debate. Burgos, 117-136. Fiedler, L. 1998 b: Conception of Lower Acheulian tools. A comparison of three sites of the Early Handaxe Culture and it's aspect of behaviour. Anthropologie 36/1-2, 69-84. Fiedler, L. 1999: Repertoires und Gene - der Wandel kultureller und biologischer Ausstattung des Menschen. Germania 77, 1-37. Fiedler, L. 2002 a: Form, Funktion und Tradition; die symbolische Präsenz steinzeitlicher Geräte. Germania 80, 405-420. Fiedler, L. 2002 b: Artefakte, Denken und Kultur. In: Tides of the Desert. Beiträge zu Archäologie und Umweltgeschichte Afrikas zu Ehren von Rudolph Kuper. Africa Praehistorica 14, Köln; 427-436. Fiedler, L. 2002: Vom Bild im Kopf zur Darstellung. In: L. Fiedler & A. Müller-Karpe (Hrsg.), Marburger Beiträge zur Prähistorischen Archäologie Nordafrikas. Kleine Schriften aus dem Vorgeschichtlichen Seminar Marburg 52. Marburg, 9-21. Fiedler, L. 2003: Was ist Paleo-Kunst? Kommentar zu R. Bednarik, The Earliest Evidence of Palaeoart. Rock Art Research (2003), 3-28. Fiedler, L. 2005: Der Urmensch als Modell des Urmenschlichen oder der anthropologische Mythos der Fakten. Erwägen Wissen Ethik 16, Heft 1, 106-109. Fiedler, L. 2007: Von klein bis groß - das Faustkeilkonzept. Fundberichte aus Hessen 42./43. (Jahrgang 2002/2003), 1-30. Fiedler, L. 2008: Beliebigkeit im kognitiven Raum? Kritik am Hauptartikel von M.N. Haidle (Kognitive und Kulturelle Evolution). Erwägen Wissen Ethik. Streitforum für Erwägungskultur 192,170-172 (Lucius et Lucius, ISSN 1610-3696). Fiedler, L. 2009: Die Steinartefakte: Formen, Techniken, Aktivitäten und kulturelle Zusammenhänge. Die mittelpaläolithischen Funde und Befunde des Unteren Besiedlungsplatzes von Buhlen, Band II. Fundberichte aus Hessen – Beihefte 5,2 Selbstverlag des Landesamtes für Denkmalpflege Hessen, Wiesbaden (2009). Gladilin, V.N. und V.I. Sitlivy 1987: On the Pre-Oldowan Developement Stage of the Society. Anthropologie 25/3, 193-204. Gabunia, L.K., O. Jöris, A. Justus, D. Lordkipanidze, A. Muschelisvili, M. Nioradze, C.C. Swisher III & A.K. Vekua - unter Mitarbeit von G. Bosinski et al. 1999: Neue Hominidenfunde des altpaläolithischen Fundplatzes Dmanisi (Georgien, Kaukasus). Archäologisches Korrespondenzblatt 29, 451-488. Leakey, M.D. 1971: Olduvai Gorge. Vol. 3, Excavations in Beds I and II, 1960-63. Cambridge. Leakey, M. & D.A. Roe 1994: Olduvai Gorge. Vol. 5, Excavations in Beds III, IV, and the Masek Beds 1998-1971. With Contributions by P. Callow, R.L. Hay, P.R. Jones, Celia K. Nyamweru and D. A. Roe. Cambridge. Roe, D.A. 1995: The Orce Basin (Andalucía, Spain) and the Initial Palaeolithic of Europe. Oxford Journal of Archaeology 14, 1-13. Sahnouni, M. 1998 a: The Lower Palaeolithic of the Maghreb. Excavations and analyses at Ain Hanech, Algeria. BAR International Series 689, Oxford. Sahnouni, M. 1998 b: The Site of Ain Hanech Revisited: New Investigations at this Lower Pleistocene Site in Northern Algeria. Journal of Archaeological Science 25,1083-1101. Stiles, D. N. & Partridge, T. C. 1997(?): Results of Recent Archaeological and Palaeoenvironmental Studies at the Sterkfontein Extension Site. South African Journal of Science 75, 346352. Wittgenstein, L. 1953: Philosophical Investigations. Oxford. Adresse: Prof. Dr. Lutz Fiedler Freiherr-vom-Stein-Strasse 10 D-35085 Ebsdorfergrund