2012 Eviction Defense Manual

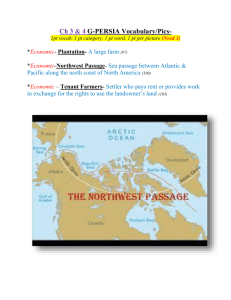

advertisement