RAB - ED Evaluation for Cardiac Chest Pain

advertisement

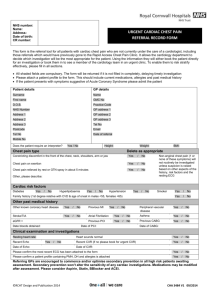

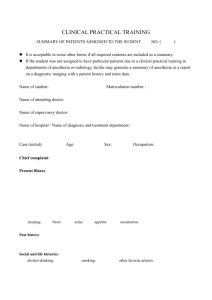

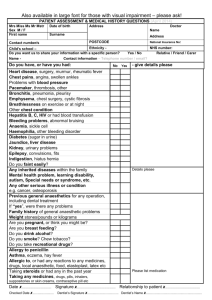

Emergency Medicine Patient Safety Foundation Newsletter The Evaluation for Cardiac Chest Pain in the ED – A Risk Management Approach Robert A. Bitterman, MD, JD, FACEP The objective of this article is to provide a practical, scientifically sound, risk management based approach to the evaluation and management of chest pain in the ED to enhance patient safety and minimize litigation losses from missed acute myocardial infarctions (AMI). Introduction: Chest pain is one of the most common complaints seen in the ED - approximately 7 million persons present to an ED annually with chest pain, representing 5 to 8% of all ED visits; [1,2,3] and coronary artery disease (CAD) is the leading cause of death in the United States - accounting for roughly 20% of all deaths each year. [ 27, 28 ] About 50% of chest pain patients presenting to the ED are hospitalized or admitted to a chest pain observation unit, and about 70% of those patients not discharged from the ED are subsequently shown to not have acute cardiac disease. [ 2, 4,18 ] Missed acute myocardial infarction causes by far the largest litigation losses for emergency physicians, approximately 30-35% of all dollars paid out in malpractice claims, though it accounts for only 10-12% of the total number of malpractice cases. [ 26, 31, 42, 47 ] It has been estimated that emergency physicians miss 2 to 6% of AMIs that present to the ED, doubling the mortality compared to patients admitted to the hospital. [21, 29, 30, 32] Furthermore, this incidence has remained relatively unchanged over the past two to three decades, except in larger centers with chest pain observation units and availability of 24/7 cardiology back-up. Recent studies provide evidence that these 'chest pain units' markedly reduce missed cardiac ischemic presentations and litigation losses. [ 22 ] The combination of the frequency of chest pain presentation, the high lethality of cardiac disease, and the risk of potentially large settlements in cases of missed AMI make this an especially important interest to the EP. Why don’t emergency physicians do a better job of diagnosing AMI and preventing litigation losses related to this entity? * * This article will not address other life-threatening diseases which must be considered in the evaluation of all patients with chest pain, such as pulmonary embolism or aortic dissection. General approach: In addressing the problem of missed MIs in the ED, the first step is to identify why cases were lost in litigation or settled with payment to the plaintiffs. After determining the area of loss and the reasons for the losses, EDs must then implement policy, procedure, and system changes to eliminate, or at least minimize litigation losses. In other words, we have to change the physician behavior which currently leads to litigation. Physician behavior modification is always, to say the least, a ‘challenge’. Available modalities to deliver the desired change include: Educate providers. (Triage, nurses, emergency physicians, ancillary personnel, cardiologists, etc.) Monitor performance, provide feedback, and continually improve performance. (CQI, audits and feedback, but ultimately this is classical peer pressure.) Motivate physicians via financial incentives. (From an insurance company perspective this tool to change physician behavior, or to penalize those who do not change to meet expected standards of behavior, includes increasing the cost of liability insurance, increasing deductibles or decreasing the amount of coverage, or potentially denying insurance altogether.) Education and CQI do work to some degree, though the effects are often transient; but as one of my mentors use to opine “‘You take their money’ is the strongest way to effectively change physician behavior”. However, if one intends to utilize financial inducements, whatever the form, then it is important to clearly set expectations in advance, so that all parties know exactly what is expected of them and the exact consequences for non-conformance. This is especially relevant when the owners of the insurance company are the very physicians whose performance is being monitored and judged. (Parenthetically, it should be noted that ‘physician behavior’ that leads to lawsuits is predominantly the physician’s attitude, interpersonal & communication skills, and documentation skills rather than the physician’s medical practice skills, but this paper will address only the medical practice aspect of dealing with chest pain in the ED.) Identify reasons for litigation losses. Unfortunately, a review of the medical literature and insurance case analysis leads to an inescapable conclusion: most missed AMIs are due to outright physician error. This also means, to look on the positive side, that opportunities exist to increase patient safety and decrease malpractice losses. The typical errors noted at litigation include: 2 1. History and physical examination errors. In about 25% of litigated cases the emergency physician simply missed relatively obvious historical and physical findings related to ischemic cardiac disease. [ 31 ] Retrospective reviews of the medical records reveal classic findings such as progressive exertional chest pain, patients with known cardiac disease describing typical ischemic pain, chest pain stories in the EMS or nursing records not seen or ignored by the physician, or an abnormal pulse or abnormal vital signs coupled with the chest pain presentation. Physician also frequently fail to get a good history for the location, duration, and severity of the pain, and presence of associated symptoms such as diaphoresis, dyspnea, palpitations, weakness, or syncope. 2. EKG interpretation errors. In about another 25% of litigated missed MI cases, the emergency physician flat-out misread the EKG. Some of these misinterpretations were obvious, such as significant ST elevation or T-wave inversions; some were subtle yet still clearly misread. In other cases the physician failed to compare the EKG with an available prior EKG which would have revealed new changes suggestive or diagnostic of acute disease. Some studies suggest that non cardiologists have a miss rate for detecting acute ischemia on an EKG of up to 20%. [ 31, 32 ] One particularly interesting study showed that 8% of emergency medicine and internal medicine residents couldn't diagnose a straightforward "tombstone" acute MI on EKG, and that an amazing 58% couldn't even diagnose complete heart block. [ 77 ] 3. Failure to detect 'atypical' presentations of cardiac ischemia. 'Atypical' presentations can delay or obscure the diagnosis of AMI, making life very difficult for emergency physicians. Up to 25 to 40% of patients with an AMI may have no chest pain, instead presenting with weakness, nausea/vomiting, dyspnea, or pain elsewhere, such as abdominal pain, back pain, shoulder pain, or jaw pain. [ 39 ] It is common for elderly patients with AMIs, particularly inferior MIs, to present with abdominal pain rather than chest pain. All patients over the age of 50 with abdominal pain not due to an obvious etiology should receive an EKG as soon as possible. Even when 'chest pain' is present, physicians fail to appreciate how often pain perceived as 'atypical' is actually pain caused by cardiac ischemia. 'Burning pain', generally associated with esophagitis, may occur in 40% or more of patients with AMI or unstable angina, and is actually more common than crushing-type pain in intermediate-risk patients. [ 49 ] Only 20-50% of AMI patients will describe their pain a 'pressure' like. A number of studies demonstrate that at least 40% of patients with AMI present with 'atypical' chest pain, and that the presence of 'typical' vs. 'atypical' chest pain has no predictive value for AMI in the ED. [45, 65, 66 ] Also, sharp pain, stabbing pain, ache pain, dull pain, pain lasting seconds, minutes or hours, pain without radiation, pain with radiation to odd areas have all each been associated with a greater than 10% rate of the AMI patient's presenting pain. [45, 49, 65, 66] In fact, the emergency physician's perception of the usual pain presentation of cardiac ischemia probably hampers recognition of AMI in the emergency department. 3 Patient populations at particular risk for missed AMI include men under the age of 40 or 45 (up to 10% of AMIs occur in patients younger than 45 years of age), women under the age of 55, minorities/patients of ethnic backgrounds, elderly patients, and patients with 'atypical' pain. [ 8, 11, 15, 17, 19, 31, 32, 33, 34 ] In summary, 'atypical' presentations of cardiac disease are actually much more typical than many emergency physicians, particularly less seasoned emergency physicians, fully appreciate. [ 44 ] 4. Failure to appreciate known science related to the diagnosis of AMI. Other factors present in cases of missed AMI in the ED include misunderstanding the role of risk factors, over-reliance on bedside maneuvers, or inapt diagnostic testing to rule out cardiac ischemia. (a.) Risk factors It is common practice to assess traditional risk factors of diabetes, hypertension, smoking, hypercholesterolemia, and family history in patients presenting to the ED with chest pain. However, these risk factors were identified as predictive of developing CAD over decades; they have not been firmly associated with or predictive of cardiac ischemia in the setting of acute chest pain in the ED (though diabetes may be somewhat predictive). Studies have shown that particularly in lower risk patients (the ones often missed in the ED) CAD risk factors are of little value in the evaluation of chest pain. [ 67, 68 ] Furthermore, the absence of risk factors does not exclude acute cardiac ischemia as the cause of a patient's chest pain. (Cocaine use (and perhaps amphetamine use) should also be elicited in the history and considered a risk factor; the ramifications of cocaine are addressed separately below.) (b.) Bedside Maneuvers (1.) Chest wall palpation. Chest tenderness, including reproducible chest wall pain from palpation, is common in patients with ACS or AMI. Various studies have show that 6 to 20% of patients admitted with confirmed AMI will have chest wall tenderness on their initial exam in the ED. [20, 32, 45] The presence of chest wall pain certainly does not eliminate the possibility of AMI. (2.) GI cocktails. GI cocktails can relieve 'chest pain', even in patients with myocardial infarction, and their use is unreliable in differentiating GI from cardiac causes of a patient's chest pain. [ 55 ] The majority of patients with chest pain due to AMI will report some relief of their chest pain after the administration of a GI cocktail, and a significant percentage of those with AMI will report complete relief of their pain with a GI cocktail. [ 49, 55 ] Relief of pain with a GI cocktail is absolutely not diagnostic. 4 (3.) Administration of nitroglycerine (NTG). Many physicians believe that relief of pain by sublingual NTG helps differentiate cardiac from non-cardiac causes of chest pain. Not true; in fact in one study 88% of patients with cardiac chest pain responded to NTG, but 92% of patients with non-cardiac chest pain also responded favorably. Relief of chest pain by sublingual NTG does not rule in cardiac disease. [ 70 ] (c.) Diagnostic testing (1). EKGs. Over half of all patients who present with acute myocardial infarction initially have a non-diagnostic EKG. Therefore, a negative initial EKG does not mean the patient does not have ischemic cardiac disease. [ 37, 38 ] Serial EKGs should be done at specified intervals or whenever the patient's symptoms change, such as the pain increases, the pain reoccurs, or diaphoresis or shortness of breath become evident. [ 39 ] Emergency physicians should never rely on a single EKG to rule out an AMI; it is not a sensitive test. Serial exams do improve detection of AMI. [ 38, 39 ] (2.) Cardiac enzymes/biomarkers. Currently available serum cardiac markers, particularly troponins, are extremely sensitive and specific for myocardial injury when used correctly. A common error made in the ED is to do a single set of biomarkers and fail to obtain a second set 8 or 12 hours later. Biomarkers may not turn positive for a number of hours after the patient with an AMI presents to the ED (for example, troponins have sensitivities of 50% within the first four hours of symptoms but are not positive in greater than 95% of AMI patient until 8 hours following symptom onset. [ 36, 40, 43, 46, 69, 71, 72 ] Thus a single measurement of biomarkers upon presentation to the ED is poorly sensitive and inadequate to rule out myocardial infarction. If your suspicion is high enough to order enzymes in the first place, your logic should remain consistent by doing serial levels over at least an 8 to 12 hour period. (An exception may be in patients of low clinical risk with a normal EKG and a negative set of enzymes drawn more than six hours after the pain ceased.) [ 36, 46, 69, 71, 72 ] It is also important to recognize that the measured time interval to expect a rise in the biomarkers, or to repeat the biomarkers, should start at the end of the patient's last episode of pain, not at the initial onset of the patient's pain. Many patients have stuttering episodes of symptoms/pain which may represent ischemia, not injury, and it may be only the last episode of pain that represents the infarction that will give rise to the biomarkers. Furthermore, biomarkers cannot identify most patients with unstable angina - a particularly problematic issue for emergency physicians. Only a third of patients with unstable angina will have positive biomarkers in the first 24 hours of their presentation. The ED will have to depend on provocative stress testing to diagnose most of these patients. [ 14, 73, 74 ] 5 5. Summary of reasons for litigation losses. What all this boils down to is that emergency physicians must accept and acknowledge that we are not very good at clinically determining whether acute cardiac ischemia is the etiology of a patient's chest pain. The standard approach of H&P, a single EKG, and chest x-ray evaluations in the emergency departments leads to the 2 to 6 percent missed acute myocardial infarction rates. Society, through the lessons of litigation has proclaimed that a failure rate of 2-6% is simply unacceptable, even if that is the standard of care in many communities. This is particularly so when today the tools and the science exist, at reasonable risk and cost to the patient, to reduce this error rate down into the 0.2 to 0.6 percent range. In other words, standard acceptable practice in many emergency departments across this country is no longer acceptable and must be changed. Unless the emergency physician can definitively determine that the etiology of the patient's chest pain is something other than AMI (E.g., pneumonia, Herpes Zoster, pneumothorax, broken ribs, GSW to the chest, etc), the pain should be assumed to be cardiac in origin until ruled out by appropriate diagnostic intervention in the ED or inpatient setting (observation, serial EKGs, serial biomarkers, and potentially cardiac stress testing.) [ 48 ] 'Atypical chest pain' or 'non-cardiac chest pain' is an exceedingly high risk diagnosis and should be avoided like the bird-flu. In fact, a very scary 15-25% of patients diagnosed in the ED with undifferentiated chest pain prove to have acute coronary ischemic disease within 30 days. [ 23, 37 ] Unexplained chest pain is due to cardiac disease until you prove otherwise! _________________________________________________________ Table 1. Scientific Truisms Related to Diagnosing AMI in the ED. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Absence of risk factors does not exclude an AMI. Relief of pain by a GI cocktail does not rule out an AMI. Chest wall tenderness does not rule out an AMI. Lack of a response to NTG is not helpful in ruling out an AMI. A single normal EKG does not rule out an AMI. One set of negative cardiac enzymes does not rule out an AMI. _________________________________________________________ What Emergency Physicians and Hospitals Must Do to Address Chest Pain in the ED. The following issues must be addressed by every hospital emergency department: 6 1. Design systems protocols that are practical, reproducible, dependable, and minimize error rates. Each hospital must examine its own resources and availability of physician expertise to determine its approach to evaluating and treating patients presenting with chest pain. Resources that need to be taken into account include chest pain observation units, biomarker measuring capabilities, electronic availability of old EKGs, continuous ST monitoring, availability of inpatient or outpatient provocative stress testing, availability of on-call cardiologists, and the facilities interventional cardiac capabilities. The systems the hospital establishes and follows should be the product of a team initiative, including emergency physicians, cardiologists, nursing, and hospital administration. The ED should carefully identify written recommendations as ‘guidelines’ only, specifically stating that they are NOT policies, protocols, or intended as a standard of care or the hospital medical screening process. (This is necessary to avoid litigation for malpractice due to ‘failure to follow your own rules’ or litigation under EMTALA for ‘failure to provide an 'appropriate' medical screening examination’.) 2. Establish criteria for triage nurses to initiate the ED's ‘chest pain guidelines’. Implementation of liberal chest pain triage guidelines, which primarily lead to earlier performance and physician reading of an EKG, significantly reduce the time between arrival and decision to treat. [ 75 ] An example of triage criteria may include: All patients over age 30 with undifferentiated chest pain are placed in high acuity areas of the ED, an EKG is done immediately, and the EKG is interpreted by the emergency physician within 10-15 minutes of the patient's arrival. 3. Establish nursing guidelines as part of the hospital's ED 'chest pain guidelines'. Nursing guidelines, once the triage criteria are initiated, may include: 1) 2) 3) Place patient in monitored bed. Attach cardiac monitor and pulse oximeter. Administer oxygen if O2 saturation < 95%. 7 4) 5) 6) 7) Establish IV access (saline lock) and draw bloods. Take vital signs. Perform an EKG and obtain old EKGs. Perform nursing assessment. If an EP is not immediately available, the nurse may do the following based on clinical judgment: 8) 9) 10) 11) 12) Administer 325mg ASA PO (If not ASA allergic & not taken ASA w/in 12 hrs.) NTG 0.4mg SL q. 5 minutes, titrate to pain up to 3 doses if BP remains stable. Order cardiac enzymes (CK-MB and troponins). MSO4 - 2 mg IVP if NTG ineffective in relieving pain and BP stable. Order portable CXR. 4. Establish clinical risk stratification parameters to guide evaluation and management algorithms. The American College of Emergency Physicians, the American Heart Association, the American College of Cardiology, and others have all published guidelines for the management of ACS in the ED. [ 50, 51, 52, 53, 54 ] Unfortunately, the evidence basis for various diagnostic approaches and risk stratification for ED patients is quite meager, and there is little data showing a level of risk that is so low that no testing is warranted. Missing an AMI can result in high mortality and high medical-legal liability, so the threshold for testing patients to improve the sensitivity of our evaluations should be very low. Thus, all protocols for evaluating patients with chest pain are designed to sensitive in capturing patients with acute ischemic disease. Using the H&P, CXR, and EKG patients can be stratified as having high, intermediate, or low probability of CAD. One practical approach, designed by the Medical College of Virginia, [ 69 ] uses a five-level stratification. Level 1 patients have ST segment elevation indicating emergent reperfusion. Level 2 patients (high-risk) have known CAD with typical symptoms, transient ST segment elevation, ST depression, or positive biomarkers. The ED management of Level 1 and 2 patients is straightforward and involves admission and consultation with cardiology. Level 3 patients (intermediate-risk) have a moderate probability for unstable angina, are now pain free, and have a normal or non-diagnostic EKG. Level 4 patients (low-risk) have a low probability for unstable angina and a normal or nondiagnostic EKG. Level 5 patients have clinically determined non-cardiac chest pain (i.e., a definitive diagnosis for their pain and can be discharged from the ED without further testing). The Level 3 and Level 4 patients, the intermediate-risk and low-risk patients, benefit the most from ED chest pain testing protocols. 8 5. Utilize chest pain testing protocols for intermediate and low-risk patients. These protocols are typically done by the emergency physicians in a 'Chest Pain Center' or unit within the hospital's ED. These patients have a non-diagnostic EKG, a negative chest xray, and no obvious non-cardiac etiology for their chest pain. If at any time in the protocol, patients develop EKG changes, positive cardiac markers, arrhythmias, deteriorate clinically, or have recurrent ischemic pain they should be reassessed and promptly admitted to the hospital. They protocols include observation, serial EKGs (and continuous ST segment monitoring in some hospitals), serial biomarkers, and provocative cardiac stress testing prior to discharge from the ED in patients who rule out for AMI by the serial studies. 6. What if you do not have a 'Chest Pain Center' in your ED? Many hospitals, particularly smaller hospitals, do not have chest pain centers to observe patients, perform serial EKGs and biomarkers, or conduct stress testing for cardiac disease before discharge from the hospital. They must utilize one of their usual ED beds to perform any serial exams or testing of their chest pain patients, and typically do not have access to immediate in-hospital stress testing. Otherwise, they must admit all these patients (which creates a whole set of different problems). Patients with clinically low-risk acute chest pain (Level 3 and Level 4 patients) for less than 12 hours with a normal EKG and a negative troponin taken at least 6 hours after the end of the pain can be safely discharged home for urgent outpatient stress testing. The risk of shortterm major cardiac events in this population is very low. [ 69, 76, 41 ] 7. Younger patients with chest pain present a unique subgroup of patients with chest pain. Patients younger that 40 years of age account for 14-15% of ED visits for chest pain and 48% of all AMIs annually, or about 40,000 AMIs per year. Approximately 5% of all patients less than age 40 presenting to the ED with chest pain are diagnosed with an ACS. [ 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 35 ] Smoking is the most prevalent risk factor in this group and a positive family history the second most prevalent factor. [ 10, 11 ] Adults younger than 40 years old without known cardiac disease who have either no cardiac risk factors or a truly normal EKG have a < 1% risk of ACS or a 30-day adverse cardiovascular event. (Cocaine users are excluded.) Adding a set of negative cardiac markers would reduce the risk of initial diagnosis of ACS or 30-day adverse cardiovascular events to < 0.2%. [ 12, 24, 25 ] Chest pain patients under age 40 with normal EKGs and no prior history of IHD may be suitable for early discharge. This rule was 98.8% sensitive and 32.5% specific in a study 9 population 769 patients, but remains to be validated by a larger, more detailed prospective study so it should not be incorporated into any hospital protocols yet. [ 23, 25, 41, 13 ] This means the rule would identify 98.8% of those who would develop an ACS within 30 days of discharge from the ED. The rule could eventually be used to limit unnecessary admissions and refer selected young patients for outpatient evaluation of their chest pain syndromes. 8. Establish EKG parameters. All patients, regardless of age, with unexplained chest pain should get an EKG. All patients over the age of 50 with abdominal pain not due to an obvious etiology should get an EKG. The hospital must be able to retrieve old EKGs in a timely fashion, preferably immediately in electronic format. Utilize instantaneous computer readings of the EKGs to help EPs diagnose acute MIs. Do not rely on a single EKG; serial exams improve detection. Left bundle branch block (LBBB) obscures the EKGs findings of ischemia. It is quite difficult, some say impossible, to diagnose MI in the presence of a left bundle; you must rely on cardiac markers and observation in such patients with chest pain. Left ventricular hypertrophy with early repolarization changes is a high-risk EKG. Ischemia may be misdiagnosed as early repolarization changes. 9. Establish cardiac biomarker parameters the ED will utilize to rule out AMI. The hospital must decide which biomarkers to use and the interval for serial testing, regardless if done in a chest pain center (CPC) or in the ED if the hospital doesn't have a CPC. There is no set standard for biotesting, though most common is the combined use of CK-MB and one of the troponins. It is traditionally felt that both of these markers require at least 6-9 hours following the onset of chest pain to be maximally reliable in identifying AMI. Most hospitals use an interval of at least 8 hours, preferably 12 hours, before repeating measurement of the biomarkers, though some of the newer protocols are studying the use of 90 to 180 minute time frames for clinically low-risk patients.[ 23, 25 ] 10. Decide how to handle patients presenting with chest pain after using cocaine. Chest pain associated with the use of cocaine is quite common, but few patients actually have an AMI (~ 6%) and the in-hospital mortality rate is less than 1%. [ 57, 58, 59, 61 ] However, 10 cocaine causes up to 25% of AMIs in patients aged 18-45, and cocaine users are 7 times more likely to suffer an AMI than non-users. There are no historical features that differentiate cocaine-associated AMI from non-cocaine-related AMI. [ 57, 63 ] Most patients with cocaine-associated chest pain continue to use cocaine on a regular basis, even after hospitalizations to rule out AMI. [ 64 ] Many have little or no idea of the cardiac dangers linked to cocaine use, such as AMI or aortic dissection, though education is usually ineffectual. Many facilities do not conduct stress testing on ED patients with chest pain believed to be due to cocaine use. [ 60, 69 ] The rate of positive stress tests is very low in this population and the number of false positives relatively high, which may lead to significant complications related to invasive diagnostic procedures. If no evidence of ischemia, AMI, or cardiovascular complications are present initially or develop over a 8-12 hour observation period (including negative serial EGKs and biomarkers), then it is reasonable to discharge these patients home without stress testing. [ 59, 60, 62] The risk of death or AMI during the 30 days post discharge is very low, even in those patients who continue to use cocaine. [ 61, 56 ] The patients should be referred to their own physicians for further follow-up or outpatient stress testing at a later time. [ 61, 56 ] 11. Decide whether to offer provocative cardiac stress testing. Determine if your facility will employ stress testing to evaluate ED chest pain patients prior to discharge. If not an option at your facility, then determine if outpatient stress testing is available in your community and within what time frame. Some clinical situations may call for stress tests within 72 hours of the ED visit; others within 30 days. Recognize the sensitivities, specificities, and limitations of the various methods of cardiac stress testing used at your particular facility. 12. Establish an ED chest pain chart documentation audit tool and CQI program. (A sample audit tool is included in Appendix A.) The intent is to provide regular feedback (and peer pressure) to the emergency physicians and department as a whole. This includes providing continuous quality improvement programs, reviewing EKGs, reviewing protocols, as well as providing system driven templates to produce adequate histories and physicals and risk management templates to drive behavior. 13. Establish on-going education regarding the evaluation of chest pain patients in the ED. 11 For example, collate a series of EKGs demonstrating the various presentations of typical and subtle changes of acute cardiac ischemia and infarction, and use them to teach emergency physicians how to diagnosis acute ischemic syndromes. 14. Decide whether to use financial incentives to drive physician behavior within the group and/or via the physician's of group's malpractice liability insurance carrier. Conclusion: Chest pain is often a difficult diagnosis and missing ischemic cardiac etiologies leads to catastrophic results. Unexplained chest pain should be considered to be due to cardiac disease until you prove otherwise. In this low-probability – high mortality and high medical-legal liability medical decision making process, the emergency physician should err on the side of patient safety. Keep these patients for serial observation, serial testing and examinations, admission, or cardiology evaluation. Table 2. Missed Myocardial Infarction: Litigation Prevention Tips 1. Chest pain is due to cardiac disease until you prove otherwise. Unless you can definitively determine the cause of the patient's chest pain, you should initiate a cardiac work-up. 2. Atypical presentations are actually very common! Most patients diagnosed with an AMI do not present with 'classic' symptoms. Be especially leery in women under the age of 55, men under the age of 40 or 45, patients of ethnic backgrounds with 'atypical' pain, and the elderly. 3. Risk factors and family history should be documented in the medical record. 4. GI cocktails are NOT helpful in ruling out cardiac ischemia. Relief of pain with a GI cocktail is not diagnostic of a gastrointestinal etiology for the patient's pain; as many as 20% of patients with an AMI get absolute total relief with a single GI cocktail. 5. Chest wall pain is relatively common with an AMI, and even ‘reproducible’ chest pain with chest wall tenderness does not rule out an AMI. 6. EKGs are critical - the old, the new, and the newly repeated. Retrieve old EKGs for comparison in a timely fashion, preferably immediately in electronic format. Utilize instantaneous computer readings of the EKGs to help EPs diagnose acute MIs. Do not rely on a single EKG; repeated exams improve detection. 12 Left bundle branch block (LBBB) obscures the EKGs findings of ischemia. It is quite difficult, some say impossible, to diagnose MI in the presence of a left bundle; you must rely on cardiac markers and observation in such patients with chest pain. Left ventricular hypertrophy with early repolarization changes is a high-risk EKG. Ischemia may be misdiagnosed as early repolarization changes. All patients, regardless of age, with unexplained chest pain should get an EKG. All patients over the age of 50 with abdominal pain not due to an obvious etiology should get an EKG. Collate a series of EKGs demonstrating the various presentations of typical and subtle changes of acute cardiac ischemia and infarction to teach the emergency physicians how to diagnosis acute ischemic syndromes. 7. Cardiac enzymes/biomarkers should be done whenever you lack a definitive reason for the patient's chest pain, and one set of enzymes is inadequate to rule out a myocardial infarction. Once you've clinically decided to order enzymes, your logic should remain consistent by doing serial levels over at least an 8 to 12 hour period. (Exceptions may be in patients of low risk with a normal EKG and a negative set of enzymes drawn more than six hours after the pain onset.) 8. Cocaine chest pain is common, particularly in inner city hospitals, but cocaine may also induce or be associated with an AMI. Serial enzyme testing with outpatient provocative testing may be a safe strategy in these patients. 9. Symptom changes in the emergency department, such as any recurrence of symptoms, worsening of symptoms or changes in symptoms warrant repeated EKG and reassessment of the patient (and documentation in the medical record). 10. When in doubt, don’t let them out! Err on the side of patient safety by keeping patients for serial observation, serial testing and examinations, admission, or cardiology evaluation. Chest pain is often a difficult diagnosis and missing ischemic cardiac etiologies results in high morbidity, high mortality, and high litigation losses. ____________________________________________________________________________ End of Table 2. ____________ 13 Appendix A. Sample ED Chest Pain Evaluation Chart Documentation Audit Tool: (Each of these is essentially a yes/no decision which can be audited for presence or absence of documentation in the ED medical record. Audits could include all the parameters, some of the parameters, or even other indicators unique to specific situations such as ‘administration of ASA in any patient diagnosed with acute ischemia/infarction’ – yes/no. The Sample Audit Tool primarily addresses the evaluation of patients presenting with chest pain. A different audit tool could be used to assess the treatment provided to those patients presenting with chest pain who are diagnosed with an AMI in the ED, addressing such items as the administration of ASA, O2, nitrates, beta-blockers, heparin, and door to cath lab times, etc.) Chest Pain Pain still present in ED Radiation Quality Same as past IHD pain (if past history of CAD) Duration Exertional pain Rest pain Nocturnal pain Associated symptoms SOB Diaphoresis N/V _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ Risk Factors History of CAD DM HTN Hyperlipidemia Family history Smoking Cocaine Amphetamines _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ Physical Exam Vital signs Pulse ox Heart exam Lungs exam ABD exam Peripheral pulses LE – DVT assessment _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ 14 CHEST PAIN Audit Tool - page 2. Diagnostic Studies EKG (s) Old EKGs reviewed Repeat EKG Door to EKG interpretation < 15 minutes CXR Cardiac enzymes Repeat cardiac enzymes 8-12 hours apart (If indicated) Medical Decision Making (MDM) Present in ED medical record Risk stratification evident Cardiology consulted for abnormal EKG/biomarkers, or other indications Treatment initiated for abnormal physical findings, vital signs, EKG, or biomarkers (see 'AMI Treatment' Audit Tool) Logically consistent conclusion Documented patient ‘stable’ or ‘unstable’ at disposition. Disposition Chest Pain Unit Admission Discharge – included appropriate DC instructions. Follow-up outpatient stress test arranged, if indicated _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------References. 1. McCaig LF, Burt CW. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2001 Emergency Department Summary. Advance Data from Vital and Health Statistics; No. 335. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, 2003. 2. Kontos MC, Jesse RL. Evaluation of the emergency department chest pain patient. Am J Cardiol. 2000; 85:32B–9B. 3. American Heart Association. 2000 Heart and Stroke Statistical Update. Dallas, TX: American Heart Association, 1999. 4. Goldman L, Cook EF, Johnson PA, Brand DA, Rouan GW, Lee TH. Prediction of the need for intensive care in patients who come to emergency departments with acute chest pain. N Engl J Med. 1996; 334:1498–504. 15 5. Lamm G. The epidemiology of acute myocardial infarction in young age groups. In: Roskamm H (ed). Myocardial Infarction at Young Age. Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag, 1981. 6. Fournier JA, Sanchez A, Quero J, Fernandez-Cortacero JA, Gonzalez-Barrero A. Myocardial infarction in men aged 40 years or less: a prospective clinical-angiographic study. Clin Cardiol. 1996; 19:631–6. 7. Fullhaas JU, Rickenbacher P, Pfisterer M, Ritz R. Longterm prognosis of young patients after myocardial infarction in the thrombolytic era. Clin Cardiol. 1997; 20:993–8. 8. Uhl GS, Farrell PW. Myocardial infarction in young adults: risk factors and natural history. Am Heart J. 1983; 105:548–53. 9. Chouhan L, Hajar H, Pomposiello JC. Comparison of thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction in patients aged <35 and >55 years. Am J Cardiol. 1993; 71:157–9. 10. Wolfe MW, Vacek JL. Myocardial infarction in the young. Chest. 1988; 94:926–30. 11. Kanitz MG, Giovannucci SJ, Jones JS, Mott M. Myocardial infarction in young adults: risk factors and clinical features. J Emerg Med. 1996; 14:139–45. 12. Klein LW, Agarwal JB, Herlich MB, Leary TM, Helfant RH. Prognosis of symptomatic coronary artery disease in young adults aged 40 years or less. Am J Cardiol. 1987; 60:1269–72. 13. Negus BH, Willard JE, Glamann DB, et al. Coronary anatomy and prognosis of young, asymptomatic survivors of myocardial infarction. Am J Med. 1994; 96:354–8. 14. Hamm CW. Cardiac biomarkers for rapid evaluation of chest pain. Circulation 2001;104;1454-56. 15. Walker NJ, Sites FD, Shofer FS, Hollander JE. Characteristics and outcomes of young adults who present to the emergency department with chest pain. Acad Emerg Med. 2001; 8:703–8. 16. Hollander JE, Valentine SM, Brogan GX Jr. Academic associate program: integrating clinical emergency medicine research with undergraduate education. Acad Emerg Med. 1997; 4:225–30. 17. Hollander JE, Lozano M Jr, Goldstein E, et al. Variations in the electrocardiograms of young adults: are revised criteria for thrombolysis necessary? Acad Emerg Med. 1994; 1:94–102. 18. Selker HP, Griffith JL, D'Agostino RB. A tool for judging coronary care unit admission appropriateness, valid for both real-time and retrospective use. A time-insensitive predictive instrument (TIPI) for acute cardiac ischemia: a multicenter study. Med Care. 1991; 29:610. 19. Goldman L, Cook EF, Brand DA, et al. A computer protocol to predict myocardial infarction in emergency department patients with chest pain. N Engl J Med. 1988; 318:797–803. 20. Lee TH, Ting HH, Shammash JB, Soukup JR, Goldman L. Long-term survival of emergency department patients with acute chest pain. Am J Cardiol. 1992; 69:145–51. 21. Christianson J, Innes G, et al. Safety and efficiency of emergency department assessment of chest discomfort. CMAJ 2004;170:1803-07. 22. Zalenski RJ, Rydman RJ, Ting S, et al. A national survey of ED chest pain centers in the United States. Am J Cardiol 1998;81:1305-09. 23. Christenson J, Innes G, et al. A clinical prediction rule for early discharge of patients with chest pain. Ann of Emerg Med 2006;47:1-10. 24. Marsan R, Shaver K, et al. Evaluation of a clinical decision rule for young adult patients with chest pain. Acad Emerg Med 2005;12:26-31. Confirmed an earlier study … See Walker NJ, Sites FD, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of young adults who present to the ED with chest pain. Acad Emerg Med 2001;8:703-708. 16 25. 'Vancouver Chest Pain Rule'. See Christenson J, Innes G, McKnight D, et al. A clinical prediction for early discharge of patients with chest pain. J Ann Emerg Med 2005;08:78; and Christenson J, Innes G, et al. A clinical prediction rule for early discharge of patients with chest pain. Ann of Emerg Med 2006;47:1-10. 26. Henry G. Patient Expectations. In: Henry G, Sullivan D, eds. Emergency Medicine Risk Management: A Comprehensive Review. 2nd ed. Dallas, TX: American College of Emergency Physicians; 1997:5. 27. Lee TH, Golden L. Evaluation of the patient with acute chest pain. N Engl J Med 2000;342:11871195. 28. Zalenski R, Shamsa F, Pede K. Evaluation and risk stratification of patients with chest pain in the emergency department. Emerg Med Clin North Am 1998; 16:495-517. 29. Aufderheide TP, Brady WJ, Gibler WB. Acute Ischemic Coronary Syndromes. In: Marx JA, Hockberger RS, Walls RM, eds. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine St. Louis: Mosby; 2002:1011-1052. 30. Rosamond WD, Chambless LE, Folsome AR, et al. Trends in the incidence of myocardial infarction and in mortality due to coronary artery disease, 1987-1994. N Engl J Med 1998;339:861-867. 31. Lee TH, Rowan GW, Weisberg MC, et al. Clinical characteristics and natural history of patients with acute myocardial infarction sent home from the emergency room. Am J Cardiol 1987;60:219-224. 32. McCarthy BD, Beshansky JR, D’Agostino RB, et al. Missed diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction in the emergency department: Results from a multicenter study. Ann Emerg Med 1993;22:579-582. 33. Bertolet BD, Hill JA. Unrecognized myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Clin 1989;20:173-182. 34. Rusnak RA, Stair TO, Hansen K, et al. Litigation against the emergency physician: Common features in cases of missed myocardial infarction. Ann Emerg Med 1989;18:1029-1034. 35. Maggioni AP, Maseri A, Fresco C, et al. Age-related increase in mortality among patients with first myocardial infarctions treated with thrombolysis. N Engl J Med 1993;329:1442-1448. 36. Hamm CW, Goldman BU, Heeschen C, et al. Emergency room triage of patients with acute chest pain by means of rapid testing for cardiac Troponin T or Troponin I. N Engl J Med 1997;337:16481653. 37. Pope JH, Aufderheide TP, Ruthazen R, et al. Missed diagnosis of acute cardiac ischemia in the ED. N Engl J Med 2000;342:1163-1170. 38. Brush JE, Brand DA, Acampora D, et al. Use of the initial electrocardiogram to predict in-hospital complications of acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 1985;312:1137-1141. 39. Fesmire F, Percy R, Bardoner J, et al. Usefulness of automated serial 12-lead ECG monitoring during the initial emergency department evaluation of patients with chest pain. Ann Emerg Med 1998;31:3. See also Emerg Med Clin NA 2001;19:269; more than half of AMI patients over the age of 85 do not have chest pain as a presenting complaint. 40. Lau J, Ioannidis JP, et al. Diagnosing acute cardiac ischemia in the emergency department: a systematic review of the accuracy and clinical effect of current technologies. Ann Emerg Medicine 2001 May;37(5)453-460. 41. Ng SM, Krishnaswamy P, et al. Ninety-minute accelerated critical pathway for chest pain evaluation. Am J Cardiol 2001;15:611-617. 42. Karcz A, Korn R, Burke MC, et al. Malpractice claims against emergency physicians in Massachusetts: 1975-1993. Am J Emerg Medicine 1996 Jul;14(4):341-345. 17 43. Evaluation of Technologies for Identifying Acute Cardiac Ischemia in Emergency Departments. Summary, Evidence Report/Technology Assessment: Number 26. AHRQ Publication No. 00Medicine031, September 2000. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/epcsums/cardsum.htm. 44. Camargo CA, Lloyd-Jones DM, Giugliano RP, et al. Characteristics and prognosis of patients with acute myocardial infarction who present with atypical symptoms. Ann Emerg Med 1998;32:supplement. 45. Panju AA, Hemmelgarn BR, Guyatt GH, et al. The rational clinical examination. Is this patient having a myocardial infarction? JAMA1998Oct 14;280(14):1256-1263. 46. Karras DJ, Kane DL. Serum markers in the ED diagnosis of AMI. Emerg Med Clin N Am 2001;19:321-337. 47. Katz DA, Williams GC, et al. Emergency physicians' fear of malpractice in evaluating patients with possible acute cardiac ischemia. Ann Emerg Med 2005;46:525-535. 48. Sullivan, DJ. Missed Myocardial Infarction: Mimimizing the Risk. ED Legal Letter 1996;7:45-56. 49. Bennett JR, Atkinson M. The differentiation between esophageal and cardiac pain. Lancet 1996;2:1123-1127. 50. Practical Implementation of the Guidelines for Unstable Angina/Non-ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction in the Emergency Department – An AHA Scientific Statement, Circulation, 24 May 2005, pp 2699-2710, and Annals of Emergency Medicine, August 2005, pp 185197. 51. ACC/AHA 2002 Guideline Update for the Management of Patients With Unstable Angina and NonST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction, American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association websites, pp 1-78. 52. 2004 ACC/AHA Guidelines for the Management of Patients With ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction: Implications for Emergency Department Practice, Annals of Emergency Medicine, April 2005, pp 363-376. 53. Clinical policy: critical issues in the evaluation and management of adult patients presenting with suspected acute myocardial infarction or unstable angina. American College of Emergency Physicians. Ann Emerg Med2000May;35(5):521-525. 54. Are We Putting the Cart Ahead of the Horse: Who Determines the Standard of Care for the Management of Patients in the Emergency Department? Annals of Emergency Medicine, August 2005, pp 198-200. 55. Wrenn K, Slovis CM, Gongaware J. Using a “GI cocktail”:A descriptive study. Ann Emerg Med 1996;28:104-105. 56. Weber JE, Shofer FS, Larkin GL, et al. NEJM 2003;348:510-517. 57. Lange RA, Hillis RD. Cardiovascular complications of cocaine use. NEJM 2001;345:351-8. 58. Hollander JE, Hoffman RF et al. Cocaine associated myocardial infarction: mortality and complications. Arch Intern Med 1995;155:1081-6. 59. Hollander JE, Hoffman RS, Gennis P, et al. Prospective multicenter evaluation of cocaine-associated chest pain. Acad Emerg Med. 1994; 1:330–9. 60. Kushman SO, Storrow AD, Liu T, et al. Cocaine associated chest pain in a chest pain center. AM J Cardiol 2000;85:394-6, A10. 18 61. Weber JE, Chudnofsky CR, Boczar M, et al. Cocaine associated chest pain: how common is myocardial infarction? Acad Emerg Med 2000:873-7. 62. Hollander JE, Levitt MA, et al. The effective recent cocaine use on the specificity of cardiac markers for diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J:1998;135:245-52. 63. Qureshi AI, Suri MF, et al. Cocaine use and the likelihood of nonfatal myocardial infarction and stroke. Circulation 2001;103:502-06. 64. Hollander JE, Hoffman RS, Gennis P, et al. Cocaine-associated chest pain: one-year follow-up. Acad Emerg Med 1995;2:179-184. 65. Lee TH, et al. Acute chest pain in the emergency room: identification and examination of low risk patients. Arch Intern Med 1985;145:65-69. 66. Gupta M, Tabas JA, Kohn MA. Presenting complaints of patients with MI who present to an urban, public hospital emergency department. Ann Emerg Med 2002;40:180-186. 67. Singh R, Tiffany B, et al. The utility of the traditional coronary artery disease risk factors in riskstratifying patients presenting to the ED with chest pain. Acad Emerg Med 2002;9:398-a 68. Jayes RL, Beshansky JR, D'Agostino RB, et al. Do patient's coronary risk factors predict acute cardiac ischemia in the ED? J Clin Epidemiol 1992;45:621-626. 69. Bean DB, Roshon M, Garvey JL. Chest pain: diagnostic strategies to save lives, time and money in the ED. Emerg Med Practice. 2003;5:1-30. 70. Shry EA, Dacus J, et al. Usefulness of the response to sublingual nitroglycerin as a predictor of ischemic chest pain in the ED. Am J Cardiol 2002;90:1264-1266. 71. Bakker AJ, Koelemay MJ, et al. Troponin T and myoglobin at admission: value of early diagnosis of AMI. Eur Heart J 1994;15:45-53. 72. Bakker AJ, Koelemay MJ, et al. Failure of the new biochemical markers to exclude AMI at admission. Lancet 1993;13:1220-1222. 73. Chandra A, Rudraiah L, Zalenski RJ. Stress testing for risk stratification of patients with low to moderate probability of acute cardiac ischemia. Emerg Med Clin N Am 2001;19:87-103. 74. Green GB, Beaudreau RW, et al. Use of Troponin T and CPK-MB subunit levels for risk stratification of ED patients with possible myocardial ischemia. Ann Emerg Med 1998;31:19-29. 75. Higgins GI, Lambrew CT, et al. Expediting the early hospital care of patients with nontraumatic chest pain: impact of a modified ED triage protocol. Am J Emerg Med 1993;11:576-582. 76. Hamm CW, Goldmann BU, et al. Emergency room triage of patients with acute chest pain by means of rapid testing for cardiac troponin T or troponin I. NEJM 1997;4:1648-1653. 77. Berger JS, et al. Competency in EKG interpretation among internal medicine and emergency medicine residents" Am J Med 2005;118:873. 19