colonials.alabaster.vases

advertisement

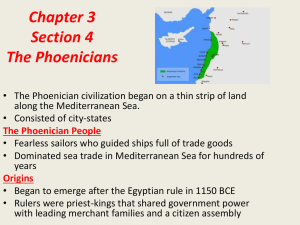

Title: Colonials, merchants and alabaster vases: the western Phoenician aristocracy Author(s): Jose Luis Lopez Castro Source: Antiquity. 80.307 (Mar. 2006): p74. Document Type: Article Abstract: Long characterised as merchants in pursuit of metals, the Phoenician settlers an the Iberian peninsula are here given an alternative profile. The author shows that a new aristocracy visible in the archaeology of bath cemeteries and settlements, was engaged in winning a social advancement denied it at home in the east. In particular, the Egyptian alabaster vases found in Spain, far from being the products of pillage or trade, were appreciated as prestige objects which often ended their days as receptacles far high status cremations. Keywords: Iberia, Egypt, Phoenician, alabaster, burial rites Full Text: Introduction The image of the Phoenicians offered in the Odyssey (13,272; 14, 287 ff.; 15,415 ft.) is of robbers and slave-traders motivated only by profit, and it is an image that has been embraced over two centuries of western scholarship. The association between Phoenicians and trade is powerful and well established (Liverani 1998). According to Greek written sources (Herod. IV, 152; Diod. V, 35, 4-5; Strab. III, 2, 9) the main reason which led Phoenicians to found new settlements in North Africa, Sicily, Sardinia, Spain and Portugal was the search for metals (Figure 1). The 'trade paradigm', as this predominant view could be called, has been sustained by European archaeologists and historians: the archaeological data relating to Phoenician colonisation are explained in terms of trade, settlements are interpreted as production sites and their inhabitants as merchants. Current scholarship assumes that Phoenician and Greek merchants initiated relationships with Late Bronze societies in Sardinia, Etruria and Tartessos during the Archaic period, resulting in the creation of 'orientalised' aristocracies (Bernardini 1982; Bisi 1984; Torelli 1981:69 ft.; Bartoloni 1984; Rathje 1984; Aubet 1984). However, less attention has been given to the social context of the Phoenician colonisers themselves. We know that aristocracies existed in eastern Phoenician cities (Tsirkin 1990: 33) and it seems logical that they should be reproduced in the west. The purpose of this paper is to see how far this might be reflected in the archaeological evidence; and, in effect, many different productive activities and stratified social groups are revealed in a society that is by no means exclusively mercantile. [FIGURE 1 OMITTED] Literary evidence for a western Phoenician aristocracy The existence of a social elite in Phoenician Levant is evidenced by some written sources. The treaty between the Assyrian king Asarhaddon and Ithobaal king of Tyre in an inscription dated to the early seventh century BC mentions a Tyrian king, as well as 'the men of the land of Tyre', as representing the city. It is significant that in the text these 'men', like the king, were able to own ships (Pettinato 1975:151 ff.). They could be interpreted as members of a higher social stratum who occupied the main religious and administration posts below the royal family (Tsirkin 1990:33 ff.) and directed sea traffic and long distance trade. Ezekiel's Against Tyre (Ezekiel 26: 16) and Isaiah in his Tyre Oracle (Isaiah 23: 2-8) mention 'sea princes' referring to the rich men who directed the economical activity of the town, and could be equated with the 'men of the land of Tyre'. This Tyrian elite has also been interpreted as consisting of 'private' merchants who initiated colonial expansion, independent of the royal palace (Bondi 1979, 1988a: 355-7; Aubet 1987). They can be seen as an 'aristocracy of merchants' with power and wealth based on trade (Bondi 1988b: 249). The story of the foundation of Carthage by Queen Elisa (Just. XVIII: 4-6) shows that Elisa, who belonged to the royal dynasty, did not travel alone: a group of 'the main citizens' of Tyre accompanied her in the expedition. Classical tradition has transmitted the name of some of the high ranking companions: Bitias, commander of the Tyrian fleet (Serv., Ad Aen. I: 738) and Barcas, the ancestor of the famous Carthaginian family of the Barca (Sil. Ital., Punica I: 72-5). An inscribed gold medallion found in a rich Carthaginian grave at Douimes and dated to 725 BC has been interpreted as belonging to a person of aristocratic position, Yada'milk son of Pidiya (Krahmalkov 1981; Gras et al. 1991:174 ft.). These were forerunners of the later Carthaginian aristocracy whose existence is well attested (Gunther 1993). A group of 'servants', once dependents of the Tyrian king Pygmalion, were also included in Elisa's expedition (Just. XVIII, 4, 12 ff.). These may have been slaves, or people with a dependent position like theger (Heltzer 1987), or free men like the 'sons of Tyre' mentioned in inscriptions (Tsirkin 1990: 33) or persons equivalent to the Tyrian 'men of the king', specialised personnel working for the palace (Tsirkin 1990: 34 ff.). Similarly, the great priest of Ashtart in Cyprus agreed to join the expedition with his family on the condition that he was permitted to keep the position of great priest of the goddess for his family (Just. XVIII: 5, 2) that is to say, to keep his privileged situation in the new city. Members of the local population are also known to have worked in the western colonial centres (Whittaker 1974: 70; Lopez Castro 1995: 45-6; Martin Ruiz 2000). Clearly, the foundation of a colony needed artisans and workers--producers to maintain nonproducers and to reproduce in the new colony their privileged social and economic position. Archaeological evidence--ranking in cemeteries Investment in tombs, the development of funerary rituals and the social value of the elements of the grave goods are the main variables to analyse social differentiation in a given society, at the same time contrasting it with evidence from settlements (Chapman et al. 1981; Lull & Picazo 1989). Wealthy graves and grave goods and particular mortuary practices reflecting ostentation and luxury were prevalent in Archaic Mediterranean aristocracies (Ampolo 1984: 470-2) and should be useful for defining colonial aristocracies too. The so-called western Phoenician necropoleis of the eighth and seventh centuries BC notably contain a relatively small number of graves, in relation to the populations implied by the settlements, and there are almost no poorly furnished graves among them. In Almunecar, the ancient Sexs, 22 graves of the eighth and seventh centuries BC were excavated in the cemetery of Cerro de San Cristobal (Pellicer 1963), but the Phoenician settlement could occupy some hectares inhabited by several hundreds of people. Another Sexitan cemetery, at Puente de Noy, contained only two chamber graves of the seventh century (Molina et al. 1981; Molina & Huertas 1985), followed by almost two hundred burials dating from the fifth to first centuries BC. Five chamber tombs at Trayamar (Schubart & Niemeyer 1976) can be associated with the eighthseventh century settlement at Morro de Mezquitilla (Schubart 1986) which extended over two hectares and was occupied by an estimated 300-500 people. In the neighbouring settlement of Chorreras (Aubet et al. 1976) of 1.5 hectares, inhabited in the eighth and seventh centuries BC, there are only a couple of graves excavated at Lagos (Aubet et al. 1991). There seems to be a small number of rich graves serving several generations of colonists. This may be contrasted with the situation in the east where Phoenician cemeteries are extensive, with a marked ranking of tombs (Prausnitz 1982; Sader 1995; Mazar 2000, 2001). Restricted access to funerary honours and rituals in the western Phoenician cemeteries in the eighth and seventh centuries should imply social segregation. The known wealthy graves should belong to an elite of non-producers. The poorer tombs corresponding to the mass of the population should be localised in other places, as for example the Puig des Molins cemeteries in Ibiza island, dated to the late seventh century BC (Costa et al. 1991; Gomez 1990), or the cemetery at Rachgoun in Argelia, dated to the late seventh and early sixth centuries BC (Vuillemot 1955). Both contained a number of burials without elaborate funeral rites. More socially representative cemeteries, with hundreds of burials both rich and poor, appeared in the Iberian peninsula only from the late seventh and sixth centuries BC to the Roman conquest. These can be attributed to the formation of the western Phoenician city-state (Schubart & Arteaga 1990; Lopez Castro 2002, 2003). We could suggest that different cemeteries serving the same settlement, particularly those featuring collective tombs, could belong to different aristocratic groups or to segmented families belonging to the original Tyrian aristocratic group. Tombs, grave goods and burial rite There are three main types of wealthy western Phoenician graves: chamber tombs built with stone blocks, with an access corridor or dromos, for example Trayamar, Jardin (Schubart & Maas 1995) and Puente de Noy; Hypogea, with a corridor or pit leading to a chamber excavated in the bed-rock, for example in Puente de Noy and Villaricos (Siret 1908; Astruc 1951), and pit graves, with a little cave excavated in the bed rock, as at Cerro de San Cristobal and Lagos (Figure 2). Funerary monuments like the sculpture of a lion found in Puente de Noy (Almagro 1983) are other indicators of social rank. [FIGURE 2 OMITTED] The principal burial rite is cremation, in contrast with eastern Phoenician rituals that used mainly inhumation (Martin 1978: 252; Bienkowski 1982: 84-7). Cremation in some ancient societies has been said to signify heroes and members of royalty (Bonnet 1988: 110) and cremation in Phoenician society has been proposed as a 'heroisation' of the deceased. Death by fire could attribute a heroic character to Carthaginian individuals linked to royalty or aristocracy, such as Queen Elisa (Just. XVIII, 6, 6) or Amilcar, the commander defeated in Himera in 480 BC (Herod. VII, 167; Grotanelli 1983; contra Bonnet 1988: 173-4). Cremation remembers the rituals of Melqart, the Tyrian god whose origins derive from royal ancestors. He was resurrected in the egersis, the annual ritual and feasts in Tyre (Bonnet 1988:107-10) and was considered 'the Lord of fire' (Ribichini 1985: 46-7). Melqart is implied in the theophore name hnmlk, which belongs to the deceased and is depicted on one of the alabaster jars used as a cinerary urn in Almunecar (Lipinski 1984: 126-7). An iconographic representation of the destination expected for the deceased is found on a medallion from burial 4-d of the Trayamar group of chamber tombs, which shows the divine residence in a mountain flanked by two falcons under the divinity symbolised by the crescent disc (Culican 1970a: 33-5). Although it is not possible to demonstrate the direct emulation of Melqart by incineration, there are many resemblances that can suggest the apotheosis of deceased individuals of high social rank. Among the grave goods, we find amphorae containing oil and wine, jugs to serve the wine and dishes to serve the food, imported Greek kotyloi to drink wine and alabaster vases for scented oil. All these elements can suggest funerary offerings of food and the celebration of funerary libation and banquets (Rathje 1991) of which we have iconographical representations in Cyprus (Culican 1982). The deposition of many fragments of dishes of red slip pottery in the fill of the pit of the hypogeum 1E of Puente de Noy (Molina 1983) could be interpreted as a ritual of this kind. Other prestige elements are gold or silver jewels like medallions, rings and objects like Egyptian-style scarabs mounted in rings. Alabaster jars and social status The usual container for cremated human remains was the alabaster jar. Around fifty alabaster jars and twenty fragments, dated to the seventh century BC, have been recorded in Phoenician colonial and some Tartessian sites in the Iberian Peninsula (Figures 3 and 4). Other than some fragments of alabaster and other stone vases found in settlement areas in Toscanos and Morro de Mezquitilla, the alabaster jars in the Iberian Peninsula are found in burials (Lopez Castro 2001-2002:144 ff.). Many of them are original Egyptian-made jars, such as the Almunecar group which includes jars with hieroglyphic inscriptions of Pharaohs of the XXII, XXV and XXVI dynasties (Gamer-Wallert 1978, Padro 1980-1985, 1984). The discovery of royal Egyptian alabaster jars in Almunecar (Figure 5) have prompted different explanations, all them so far conforming to the 'trade paradigm'. Pillaging or trading with stolen objects is explicit or implicit in almost all the hypotheses, for example pillage of the Egyptian royal tombs of Tinis (Maluquer 1963: 59; Gamer-Wallert 1973: 408, 1978: 224-5) or pillage of the royal storerooms in the palace of king Abdimilkuti of Sidon, in the Asarhaddon campaign of 677 BC and subsequent Phoenician trade of the booty (Culican 1970b: 30-1). In another hypothesis, Phoenician merchants obtained the alabaster jars from Assyrians out of the booty gained after the second invasion of Egypt in the first third of the seventh century BC (Pernigotti 1988: 275-6). There are several objections to these interpretations, including matters of chronology (Padro 1984:13; Aubet et al. 1991: 21). The pillaging of the palace of Abdimilkuti of Sidon by the Assyrians was more recent than some of the tombs of Almufiecar, now dated to the eighth century (Negueruela 1981; Aubet et al. 1991:21; Mederos & Ruiz 2002) and the same argument can be applied to the second Assyrian invasion of Egypt. In any case, there have been too many single alabaster jars found in the Iberian peninsula for them all to have been stolen. [FIGURES 3-5 OMITTED] In ancient Egypt, alabaster objects were one of the main status symbols as presents of the pharaohs to the gods or to other kings. Alabaster was worked from Old Kingdom times (Breasted 1903: II, 323) but it was in the New Kingdom that alabaster objects were widely employed (von Bissing 1939). As well as funerary vessels, the stone was used to make divine and royal statues (Breasted 1903: II, 906; IV, 302,988 and 988I, n.a) or employed as a noble material to build the residences, altars or thrones for gods and pharaohs (Breasted 1903: II, 375; III, 525,529). Alabaster was used as a rich gift to the gods, like cedar, gold and precious stones (Breasted 1903: II, 544; IV, 390). Gifts to the gods mentioned in inscriptions of the XXII dynasty included 'all the vessels of gold and silver and every splendid costly stone' (Breasted 1903: II, 615; IV, 730). In archaeological contexts, groups of alabaster vessels have been found in the Palace of Apries (von Bissing 1939: 139), and many of them were recorded in graves in the royal necropolis of Tanis, Tell Yehudie (see for instance von Bissing 1907, 1939:138 ff.) and in Nubia in royal cemeteries at El Kurru and Nuri (Dunham 1950, 1955). Egyptian pharaohs used alabaster jars in their external relations policy as diplomatic gifts of the highest value. Kings of the XVIII dynasty Akenaton, Horembeb and Ramses II sent alabaster jars with royal inscriptions as presents to Ugarit, and some centuries later Osorkon II of the XXII dynasty sent to Byblos a statue with his portrait and alabaster jars to kings Omri and Akab of Samaria (Kitchen 1973: 324; Reisner et al. 1924: 131-2, 247, 333-7). The alabaster jar found in the royal palace of Assur, which was part of the booty that king Asarhaddon took of Abdimilkuti's palace in Sidon with other alabaster vessels (as shown by Assyrian inscriptions on it) originated as a diplomatic gift (Preusser 1955:21 ff.; Padro 1984: 13-37, n. 70; Culican 1970b: 31). The jar was originally sent by the king Takeloth (von Bissing 1940:157) many years before to a Sidonian king in the context of the foreign policy of the XXII dynasty of alliances with Levantine kingdoms (Leclant 1968:11 ff., Kitchen 1973: 324). King Abdimilkuti of Sidon kept alabaster jars in the treasury of his palace before the Assyrian victory (Preusser 1955: 21-2). Alabaster jars are recorded in royal residences such as the palace of Nimrud (Mallowan 1966:16970) and the Assur palace of Assurbanipal II. Alabaster and stone vases were containers for wine and perfume, goods reserved for the consumption of kings and members of the court. Hieroglyphs on the alabaster jars from graves 1 and 15 of Almunecar has revealed that the jars had once contained wine (Gamer-Wallert 1973: 405, 1978: 224-5; Padro 1983: 218-20, 1984: 35-7). The text is similar to another inscription on an alabaster jar found in Assur (Preusser 1955: 22, e). But perfumed oil was the most probable content of these vessels. Chemical analyses of the residues conserved in an Egyptian alabaster jar of the XVIII dynasty have been identified as the remains of products associated with cosmetics or perfume (Wadsten 1978: 18). One of the Assur vessels has an inscription about the content: 'oil of the princes' (Preusser 1955:21, 2). Around 525 BC, the Persian king Cambises sent to an Ethiopian king a gift consisting of gold, purple clothes and an alabaster vase full of perfumed oil (Herod. III, 20, 1). In some cases the alabaster jars were repaired; for example, one from the Almunecar cemetery (Molina & Padro 1983: 45), and it is remarkable that fragments of vases were introduced in Phoenician chamber-tombs and in Tartessian tumuli (Lopez Castro 2001-2002: 147), probably because alabaster objects were high status indicators in themselves. Thus alabaster jars were gifts of the highest value which always appear in our sources of information associated with divinity or royalty, and on the ground in sacred or royal spaces such as temples, palaces and royal graves in Egypt. In the palaces of Assyria, Sidon or Samaria they arrived as royal gifts and containers of prestige products for exclusive consumption. However, though some scholars maintain that Egyptian alabaster jars arrived in Phoenicia as royal Egyptian gifts, their presence in the Iberian peninsula has been generally explained as the result of trade to the West particularly in the seventh century BC (Leclant 1968:11; Culican 1970b: 30; Padro 1984: 13). Even though a prestige role has been recognised for alabaster jars, their presence in western Phoenician graves is attributed to rich artisans and merchants (Aubet 1994; Aubet et al. 1991 : 21; Frankenstein 1997:192-3). Social difference in settlements Drawing on the results of excavation, houses in Phoenician settlements are generally very simple, with a plan of two or three rooms built using poor architectural materials (Dies Cusi 2001:80 ff.). But significant exceptions can be found (Figure 6). The first example is Building C at Toscanos, interpreted as a storeroom (Niemeyer 1986:113) because many amphora sherds were found there, or alternatively seen as a 'market place' (Aubet 1997). Building C is 165[m.sup.2] and is connected by stone stairs with a second building placed at a lower level; Building H has seven rooms disposed around a central courtyard enclosing an area of 110[m.sup.2]. Some alabaster jar fragments and stone vases have been recorded in Toscanos, one of them in Building C (Lindemann et al. 1972: 143), and a palatial function has been proposed for Building H (Prados 2001-2002), which has been seen as a precedent of the sixth century BC complex of Cancho Roano, interpreted as a Tartessian palace (Almagro & Dominguez 1988-1989: 368-9). In Morro de Mezquitilla another singular building of the first Phoenician phase, House K (Schubart 1986), can be distinguished. It has 16 rooms and covers 190[m.sup.2], although the complete plan of the house is yet to be excavated. A third example is provided by the complete plan of a complex colonial building recently excavated at Abul in Portugal. It has two construction phases that follow a similar pattern to that seen in Toscanos: a dozen rooms and stores surrounding a central courtyard, and a tower was added to the building. The Abul complex has been interpreted as a 'commercial residence' in which people of the highest social rank should be present (Mayet & Tavares 2000: 160 ff., 167). [FIGURE 6 OMITTED] Discussion According to the new radiocarbon dates, chronologies proposed for western Phoenician colonisation begin around 900/800 BC (Castro et al. 1996:192 ff.; Tortes Ortiz 1998: 5860; Nijboer 2002: 28-9; Docter et al. forthcoming; Mederos forthcoming). The evidence from cemeteries and from settlements imply the presence of an upper class, which is not purely mercantile, in the western Phoenician colonies from that time. Among the more powerful signals of this class are the alabaster vessels, which in my opinion need not have a very different social function in the western colonial foundations than in the eastern Mediterranean in the same period. If members of Egyptian royal families and dignitaries used alabaster canopic vases to contain their viscera, the western Phoenicians of high social status could use alabaster jars to contain the ashes of their dead. We have seen that the foundation of Carthage was conducted by members of the royal dynasty of Tyre and of the Tyrian aristocracy. It is possible that other colonial settlements could have been founded by aristocrats. Some alabaster vessels could then have arrived as personal belongings, and Egyptian vases with royal inscriptions could originally have been royal gifts redistributed by Phoenician kings between secondary members of royal families and relatives of Phoenician aristocracy, to be inherited by their descendants and reach farther west some generations after. The 'genealogy' of the object gave more prestige to the owner (Ampolo 1984: 471-3). Other alabaster jars, even if not properly royal gifts, should have the same social function as a symbol of high social status to be used as cinerary urns in colonial cemeteries. Most likely these alabaster vases originally contained rare imported perfume, re-used for funerary purposes. Only more specific analyses on the possible internal residues remaining in the alabaster jars found in the Iberian Peninsula could supply a more secure explanation. If the alabaster vessels initially define a colonial aristocracy of oriental origins, their social practices were extended to an emergent indigenous aristocracy as indicated by the Tartessian graves and their gravegoods. In fact, the alabaster jars found in Tartessian graves have been seen as proof of an originally Phoenician ritual consisting of the use of perfume, which served to define the features of the Tartessian aristocracy (Tortes Ortiz 1999: 155-6). Similarly, the few large western Phoenician buildings known until now could be interpreted as aristocratic houses. They may be associated with aristocratic families resident in small colonial settlements, and perhaps equate to the 'men of the land of Tyre' mentioned in written sources (Pettinato 1975; Tsirkin 1990). The colonial aristocracy may have been composed our of a hereditary eastern aristocracy or by groups emigrated to the far west seeking a social position similar to that of the eastern aristocracies, or perhaps by the exercise of both factors. Conclusion The presence of aristocratic groups in western colonial settlements throws light on the causes and origins of the Phoenician colonisation. The exploitation of metals and the expansion of trade networks have long been thought to provide the main impetus for the movement westwards. But social incentives can now also be seen at work: the winning or maintenance of privileged social position in a new world by people that perhaps could not expect to gain or keep it in the east. We know that royal families in Phoenician towns were large and extended, including 'poor relations' of limited economic means (Tsirkin 1990). However, we should not altogether disregard the effects of external Assyrian pressure on the Phoenician kingdoms from the ninth to seventh centuries BC (Liverani 1988: 696-7; 784 ff.) or the consequences of internal political and dynastic disagreements, which provided the context for Queen Elisa's foundation of Carthage, as other causative factors. These factors also help to explain the presence in the western colonies of groups that brought, and diffused into local elites, distinctive eastern Mediterranean aristocratic social practices of life and death. Acknowledgements This paper was developed in the research project MCYT-BHA2000-1348. I am really grateful to the editor for his comments and general improvement of the final English version. My thanks to R. Docter and A. Mederos for allowing me to read their forthcoming papers. Received: 24 March 2004; Accepted." 9 July 2004: Revised: 28 July 2004 References ALMAGRO GORBEA, M. 1983. Los leones de Puente de Noy. Un monumento torriforme funerario en la Peninsula Iberica, in F. Molina (ed.) Almunecar, Arqueologia e Historia: 89-106. Granada: Caja Provincial de Ahorros. ALMAGRO GORBEA, M. & A. DOMINGUEZ. 1988-1989. El palacio de Cancho Roano y sus paralelos arquitectonicos y funcionales. Zephyrus XLI-XLII: 340-82. AMPOLO, C. 1984. Il lusso nelle societa arcaiche. Note preliminari sulla posizione del problema. Opus III: 469-76. ASTRUC, M. 1951. La necropolis de Villaricos. Madrid: Ministerio de Educacion Nacional. AUBET, M.E. 1984. La aristocracia tartesica durante el periodo orientalizante. Opus III: 445-68. --1987. Tiro y las colonias finicias de Occidente. Barcelona: Ediciones Bellaterra. --1994. Tiro y las colonias finicias de Occidente. Edicion ampliada y puesta al dia. Barcelona: Editorial Critica. --1997. A Phoenician market place in southern Spain, in B. Pongratz-Leisten, H. Kutne & P. Xella (ed.) Ana sadi Labnani lu allik. Beitrage zu altorientalischen und mittelmeerischen Kulturen. Fetschrift fur Wolfgang Rollig. 11-22. Neukirch: Butzon & Becker. AUBET, M.E. et al. 1991. Sepulturas fenicias en Lagos (Velez-Malaga, Malaga). Sevilla: Consejeria de Cultura. AUBET, M.E., G. MAASs-LINDEMANN & H. SCHUBART. 1976. Chorreras. Un establecimiento fenicio al Este de la desembocadura del Algarrobo. Noticiario Arqueologico Hispano 6:91-138. BARTOLONI, G. 1984. Riti funerari dell'aristocrazia in Etruria e nel Lazio. L'esempio di Veio. Opus III: 13-25. BERNARDINI, P. 1982. Le aristocrazie nuraghiche nei secoli VIII e VII a.C. La Parola del Pasato 203: 81-101. BIENKOWSKI, P.A. 1982. Some Remarks on the Practice of Cremation in the Levant. Levant XIV: 80-9. BISI, A.M. 1984. La questione orientalizante in Sardegna. Opus III: 429-44. BONDI S.F. 1979. Economia fenicia. Impresa privata e ruolo dello Stato. Egitto e Vicino Oriente 1: 139-49. --1988a. Sull'organizzazione dell'attivita commerciale nella societa fenicia. Stato, economia, lavoro nel Vicino Oriente Antico: 348-62. Milano: Istituto Gramsci Toscano. --1988b. Problemi della precolonizzazione fenicia nel Mediterraneo centro-occidentale, in E. Acquaro et al. (ed.) Momenti precoloniali nd Mediterraneo antico: 241-55. Roma: Academia Belgica-Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche. BONNET, C. 1988. Melqart. Cultes et mythes de l'Heracles tyrien en Mediterranee. Namur: Peeters Publishers-Presses Universitaires de Namur. BREASTED, J.H. 1903 (1988). Ancient records of Egypt I-IV. London: Histories and Mysteries of Man. CASTRO, P.V., V. LULL & R. MICO. 1996. Cronologia de la Prehistoria Reciente de la Peninsula Iberica y Baleares (c. 2800 cal ANE). BAR International Series 652. Oxford: Archaeopress. CHAPMAN, R.W., I. KINNES & K. RANDSBORG (ed.) 1981. The archaeology of death. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. COSTA, B., J.H. FERNANDEZ & C. GOMEZ. 1991. Ibiza fenicia: la primera fase de la colonizacion de la isla (siglos VII y VI a.C.). Atti del II Congresso Internazionale di Studi Fenici e Punici, Roma 1987 II: 759-95. Roma: Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche. CULICAN, W. 1970a. Problems of Phoenico-Punic Iconograpby. A contribution. Australian Journal of Biblical Archaeology I (3): 28-57. --1970b. Almunecar, Assur and the Phoenician penetration of the western Mediterranean. Levant II: 28-36. --1982. Cesnola bowl 4555 and other Phoenician bowls. RStudFen X: 13-32. DIES CUSI, E. 2001. La influencia de la arquitectura fenicia en las arquitecturas indigenas de la Peninsula Iberica (s. VIII-VII), in D. Ruiz Mata & S. Celestino (ed.) Arquitectura oriental y orientalizante en la Peninsula Iberica: 69-121. Madrid: Centro de Estudios del Proximo Oriente--Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cientificas. DOCTER, R.F. et al. forthcoming. Radiocarbon dates on animal bones in the earliest levels of Carthage, in G. Bartoloni, F. Delpino, R. De Marinis & P. Gastaldi (ed.) Oriente e Occidente: metodi e discipline a confronto. Rifflessioni sulla cronologia dell'eta del ferro italiana. DUNHAM, D. 1950. The Royal Cemeteries of Kush, El Kurru. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. --1955. The royal cemeteries of Kush. II. Nuri. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts. FRANKENSTEIN, S. 1997. Arqueologia del colonialismo. El impacto fenicio y griego en el sur de la Peninsula Iberica y el suroeste de Alemania. Barcelona: Editorial Critica. GAMER-WALLERT, I. 1973. La inscripcion del vaso de alabastro de la tumba numero 1 de Almunecar (Granada). XII Congreso Nacional de Arqueologia, Jaen, 1971: 401-08. Zaragoza: Universidad de Zaragoza. --1978. Agyptische und agyptisierende Funde von der Iberischen Halbinsel. Wiesbaden: Reichert. GOMEZ BELLARD, C. 1990. La colonizacion fenicia en la isla de Ibiza. Madrid: Ministerio de Cultura. GRAS, M., P. ROUILLARD & J. TEIXIDOR. 1991. El universo fenicio. Madrid: Mondadori. GROTANELLI, C. 1983. Encore un regard sur les buchers d'Amilcar et d'Elissa. Atti del I Congresso Internazionale di Studi Fenici e Punici, Roma, 1979 II: 439-41. Roma: Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche. GUNTHER, L. 1993. Die Karthagische Aristokratie und ihre Uberseepolitik im 6. Und 5. Jh v. Chr. Klio 75: 76-84. HELTZER, M. 1987. The ger in the Phoenician society. Phoenicia and the East Mediterranean in the first millenium BC, Studia Phoenicia V: 309-14. Leuven: Peeters. KITCHEN, K.A. 1973. The third intermediate period in Egypt. Warminster: Aris & Phillips. KRAHMALKOV, C.R. 1981. The foundation of Carthage, 814 B.C. The Douimes pendant inscription. Journal of Semitic Studies 26: 177-91. LECLANT, J. 1968. Les relations entre l'Egipte et la Phenicie ou voyage d'Ounamon a l'expedition d'Alexandre, in W.A. Ward (ed.) The role of the Phoenicians in the interaction of Mediterranean civilizations: 9-31. Beirut: American University of Beirut. LINDEMANN, G., H.G. NIEMEYER & H. SCHUBART. 1972. Toscanos, Jardin und Alarcon. Vorbericht fiber die Grabungskampagne 1971. Madrider Mitteilungen 13: 12557. LIPINSKI, E. 1984. Vestiges pheniciens d'Andalousie. Orientalia Lovaniensia Periodica 15: 81-132. LIVERANI, M. 1988. Antico Oriente. Storia, societa, economia. Roma-Bari: Editori Laterza. --1998. L'immagine dei fenici nella storiografia occidentale. Studi Storici 39 (1): 5-22. LOPEZ CASTRO, J.L. 1995. Hispania Poena. Los fenicios en la Hispania romana. Barcelona: Editorial Critica. --2001-2002. Vasos de alabastro de Abdera y Baria. Ocnus 9-10: 137-53. --2002. Las ciudades fenicias occidentals, in J.L. Jimenez & A. Ribera (ed.) Valencia y las primeras ciudades romanas de Hispania: 61-72. Valencia: Ajuntament de Valencia. --2003. La formacion de las ciudades fenicias occidentals. Byrsa. Rivista di arte, cultura e archeologia del Mediterraneo punico 2: 69-120. LULL, V. & M. PICAZO. 1989. Arqueologla de la muerte y estructura social. Archivo Espanol de Arqueologia 62: 5-20. MALLOWAN, M.E.L. 1966. Nimrud and its remains. London: Collins. MALUQUER, J. 1963. Descubrimiento de la necropolis de la antigua ciudad de Sexi en Almunecar (Granada). Zephyrus XIV: 57-61. MARTIN RUIZ, J.M. 2000. Ceramicas a mano en los yacimientos fenicios de Andalucia, in M.E. Aubet & M. Barthe1emy (ed.) Actas del IV Congreso Internacional de Estudios Fenicios y Punicos, Cadiz 1995 IV: 1625-30. Cadiz: Universidad de Cadiz. MARTIN WEDARD, U. 1978. A proposito della cremazione arcaica fenicio-punica. Studi Micenei ed Egeo Anatolici 19: 247-52. MAYET, F. & C. TAVARES DA SILVA. 2000. L'etablissement phenicien d'Abul. Paris: De Boccard. MAZAR, E. 2000. Phoenician family tombs at Achziv. A chronological typology (1000400 BCE), in A. Gonzalez Prats (ed.) Fenicios y territorio: 189-221. Alicante: Instituto Alicantino de Cultura. --2001. The Phoenicians in Achziv. The southern cemetery. Jerome L. Joss Expedition. Final Report of the Excavations 1988-1990. Cuadernos de Arqueologia Mediterranea 7. Barcelona: Publicaciones del Laboratorio de Arqueologla de la Universidad Pompeu Fabra. MEDEROS MARTIN, A. forthcoming. La cronologia fenicia. Entre el Mediterraneo Oriental y el Occidental. Anejos de Archivo Espanol de Arqueologia XXXIII. MEDEROS MARTIN, A. & L.A. RUIZ CABRERO. 2002. La fundacion de Sexi-Laurita (Almunacer-Granada) y los inicios de la penetracion fenicia en la vega de Granada. Spal 11:41-7. MOLINA FAJARDO, F. 1983. La tumba fenicia 1E de Puente de Noy, in F. Molina Fajardo (ed.) Almunecar, Arqueologia e Historia: 57-88. Granada: Caja Provincial de Ahorros. MOLINA FAJARDO, F. & J. PADRO 1983. Nuevos materiales procedentes de la necropolis del Cerro de San Cristobal (Almunecar, Granada), in F. Molina Fajardo (ed.) Almunecar, Arqueologia e Historia: 35-55. Granada: Caja Provincial de Ahorros. MOLINA FAJARDO, F. et al. 1981. Almunecar en la Antiguedad. La necropolis feniciopunica de Puente de Noy. Granada: Caja Provincial de Ahorros. MOLINA, F. & C. HUERTAS. 1985. La necropolis fenicio-punica de Puente de Noy. II. Granada: Diputacion Provincial- Ayuntamiento de Almunecar. NEGUERUELA, I. 1981. Zur Datierung der westphonizischen Nekropole yon Almunecar, Madrider Mitteilungen 22: 211-28. NIEMEYER, H.G. 1986. El yacimiento de Toscanos: urbanistica y funcion, in G. del Olmo & M.E. Aubet (ed.) Los fenicios en la Peninsula Iberica I: 109-26. Sabadell: Editorial Ausa. NIJBOER, B. 2002. Een debat over chronologieen. Tijdschrift voor Mediterrane Archeologie 26: 23-32. PADRO, J. 1980-1985. Egyptian-type documents from the Mediterranean littoral of the Iberian peninsula before the Roman conquest. Leiden: Brill. --1983. Las inscripciones egipcias de la Dinastia XXII procedentes de Almunecar (provincia de Granada). Aula Orientalis 1: 215-25. --1984. Materiales egipcios del Cerro de San Cristobal, Almunecar (Granada). Hallazgos de la campana de 1963, in F. Molina Fajardo (dir.) Almunecar, Arqueologia e Historia II: 11-78. Granada: Fundacion Banco Exterior. PELLICER CATALAN, M. 1963. Excavaciones en la necropolis punica "Laurita" del Cerro de San Cristobal (Almunecar, Granada). Madrid: Ministerio de Educacion y Ciencia. PERNIGOTTI, S. 1988. Aspetti dei rapporti tra la civilta fenicia e la cultura egiziana, in E. Acquaro et al. (ed.) Momenti precoloniali nel Mediterraneo antico: 267-76. Roma: Academia Belgica-Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche. PETTINATO, G. 1975. I rapporti politici di Tiro con Assiria alia luce del 'trattato tra Asarhaddon e Baal'. RStudFen III: 145-60. PRADOS MARTINEZ, F.J. 2001-2002. Almacenes o centros redistribuidores de caracter sacro?. Una reflexion en torno a un modelo arquitectonico tipificado en la protohistoria mediterranea. Estudios Orientales 5-6: 173-80. PRAUSNITZ, M.W. 1982. Die Nekropolen yon Akhziv und die Entwicklung der keramik von 10 bis zum 7 Jahrhundert v.Chr, in Akhziv, Samaria und Ashdod, in H.G. Niemeyer (ed.) Phonizier im Westen. Koln: P. von Zabern. PREUSSER, C. 1955. Die Palaste in Assur. Berlin: Gebr. Mann. RATHJE, A. 1984. I keimelia orientale. Opus 3: 341-50. --1991. Il banchetto presso i fenici. Atti del II Congresso Internazionale di Studi Fenici e Punici, Roma, 1987 III: 1165-68. Roma: Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche. REISNER, G.A., C.S. FISHER & D.G. LYON. 1924. Harvard excavations at Samaria. 1908-1910. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. RIBICHINI, S. 1985. Poenus Advena. Gli dei fenici e l'interpretazione classica. Roma: Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche. SADER, H. 1995. Necropoles et tombs pheniciennes du Liban, Cuadernos de Arqueologia Mediterranea 1: 15-30. SCHUBART, H. 1986. El asentamiento fenicio del siglo VIII a.C. en el Morro de Mezquitilla (Algarrobo, Malaga), in G. del Olmo & M.E. Aubet (ed.) Los fenicios en la Peninsula Iberica I: 59-83. Sabadell: Editorial Ausa. SCHUBART, H. & O. ARTEAGA. 1990. La colonizacion fenicia y punica. Historia de Espana dirigida por M. Domtnguez Ortiz I: 431-69. Barcelona: Editorial Planeta. SCHUBART, H. & G. MAAS-LINDEMANN. 1995. La necropolis de Jardin. Cuadernos de Arqueologia Mediterrinea 1: 57-213. SCHUBART, H. & H.G. NIEMEYER. 1976. Trayamar. Los hipogeos fenicios y d asentamiento en la desembocadura del Algarrobo. Madrid: Ministerio de Educacion y Ciencia. SIRET, L. 1908 [1988]. Villaricos y Herrerias. Madrid: Museo Arqueologico Nacional. TORELLI, M. 1981. Storia degli etruschi. Bari: Editori Laterza. TORRES ORTIZ, M. 1998. La cronologia absoluta europea y el inicio de la colonizacion fenicia. Complutum 9: 49-60. --1999. Sociedad y mundo funerario en Tartessos. Madrid: Real Academia de la Historia. TSIRKIN, J.B. 1990. Socio-political structure of Phoenicia. Gerion 8: 29-43. VON BISSING, F.W. 1907. Catalogue generale des antiquites egyptiennes du Musee du Caire, no 18065-18793. Steingefasse. Vienne: Adolf Holzhauser. --1939. Studien zur Altessen Kultur Italiens IV. Alabastra. Studi Etruschi XIII: 131-78. --1940. Agyptischen und agyptisierende Alabastergefasse aus den Deutschen Ausgrabungen in Assur. Zeitschrift fur Assyriologie und Vorderasiatische Archaologie (NF) 12: 159-61. VUILLEMOT, G. 1955. La necropole punique du phare dans l'ile de Rachgoun. Libyca III: 7-62. WADSTEN, T. 1978. Characterization of the solid residue in an ancient Egyptian alabaster jar. Medelhaus Museum Bulletin 13: 14-8. WHITTAKER, C. 1974. The western Phoenicians: colonisation and assimilation. PCPhS 200 (n.s. 20): 58-79. Jose Luis Lopez Castro, University of Almeria, Almeria, Spain (Email:jllopez@ual.es) Castro, Jose Luis Lopez Source Citation Castro, Jose Luis Lopez. "Colonials, merchants and alabaster vases: the western Phoenician aristocracy." Antiquity 80.307 (2006): 74+. Academic OneFile. Web. 15 Feb. 2012. Document URL http://go.galegroup.com/ps/i.do?id=GALE%7CA145024057&v=2.1&u=lom_accessmich &it=r&p=AONE&sw=w Gale Document Number: GALE|A145024057