Geographic Range

advertisement

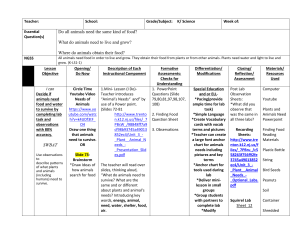

Sciurus niger Eastern Fox Squirrel Geographic Range The Eastern Fox Squirrel is widely distributed across the eastern and central parts of the United States. It ranges from North Dakota east to the Atlantic Ocean and south to Florida and extreme northeast Mexico. It becomes less common or entirely absent in New England northeast of central New York. In Wisconsin, this species is found in forested areas of the entire state. However, it is less common in extreme northeastern Wisconsin and the Upper Peninsula of Michigan (Burt 1986). Eastern Fox Squirrels have been introduced into several cities in the western United States due to their aesthetic appeal. These cities include Seattle, Washington; San Francisco, California; and Portland, Oregon (Burt 1986). Physical Characteristics The Eastern Fox Squirrel is the largest tree squirrel in the eastern United States. The head and body range from 48-73 cm in length including the tail, which is 25-30 cm long. Weights vary between 550 and 1400 grams. Throughout the northern part of most of its range, Eastern Fox Squirrels have a yellowish-orange belly and chest. The upper parts are a rusty grayish-brown. The long bushy tail is often conspicuously edged with buff-colored hairs. Though the above characteristics are prevalent, Fox Squirrels can have three distinct color phases. The phases include the aforementioned phase, a black phase, or a red phase. This variation in pelage often causes confusion with Eastern Gray Squirrels and Red Squirrels. The black phase is referred to as melanistic. Polymorphism describes the occurrence of multiple color phases (Mammals of Texas: Online Edition; Georgia Wildlife Website, Mammal Fact Sheet). External characteristics are the most useful cues for discerning Fox Squirrels in the field; however, there are many internal traits that classify them as tree squirrels. The skull and teeth of squirrels, including the Eastern Fox Squirrel are quite unique. Squirrels lack canine teeth; rather they exhibit a large gap in the lower and upper jaw known as the diastema, which is common to all rodents. Fox Squirrels have 1 incisor, 0 canines, 1 premolar, and 3 molars on each side of the upper and lower mandibles. The Gray Squirrel can be distinguished from the Fox Squirrel by the presence of a second upper pre-molar. Incisors of squirrels are enlarged, chisel-shaped, and grow continuously throughout the animal’s life (Steele and Koprowski 2001). Squirrels, including the Fox Squirrel have two important enlarged jaw muscles. The masseter is a cheek muscle that allows free movement of the lower jaw, and the temporalis generates great vertical force from the upper and lower jaws to allow strong chewing (Steele and Koprowski 2001). Natural History Food Habits Eastern Fox Squirrels favor high-energy nuts, including walnut, hickory, pecan, paw-paw, and acorns. Any type of vegetation that is physically available to Fox Squirrels can and will be consumed. This includes many types of crops such as corn, potatoes, and carrots, as well as berries and flowers. Squirrels have a minor reputation as agricultural pests because of this. Fox Squirrels can be carnivorous as well. Animals eaten may include young birds and rodents, as well as various insects. They also prey upon bird nest eggs before the young have hatched The above menu varies depending on season. Nuts and seeds are more commonly eaten in the winter, while flowers and fruits are consumed more often during the warmer months. Recently with the increased popularity of bird feeding, Eastern Fox Squirrels have become a more common animal in the backyard setting. There they consume high-energy seeds, suet, and corn, which may or may not be intended as food for squirrels (Woods 1980). Reproduction Female Eastern Fox Squirrels generally do not reproduce until between one and two years of age. Due to their reliance on food availability, Fox Squirrels time their production of young with the greatest availability of mast. Since this occurs in spring and fall, Fox Squirrels mate once in January or February and once in May or June. Though they can mate twice a year, Fox Squirrels rarely produce two litters of offspring within the same year (Harnishfeger et al. 1978). The gestation period for Fox Squirrels is about 44 days. Litter sizes range from 2 to 4 offspring with 3 being the most common and numbers as high as 7 being extremely rare. Interestingly, this would represent an investment for the female equal to 20% of her body mass. Young are born naked and blind and are about 10 cm long at a mass of 15 g (Woods 1980). Female squirrels play the entire role of caring for young, while the male moves on without forming a pair bond. (Koprowski 1993a, 1993b). Behavior In late summer and early fall, Fox Squirrels spend much time collecting and caching large quantities of nuts. They are buried individually and collected again during the winter months. Contrary to popular belief squirrels don’t remember where each food item is buried, rather they have an excellent sense of smell, which helps them locate hoarded items (Gurnell 1987). Recent research revealed more about caching behavior. Through a series of manipulations, researchers found that squirrels are able to perceive the tradeoff between cost spent caching and value of a food item. Easily stored food is immediately cached. Squirrels don’t waste time trying to cache non-storable food; rather they eat it immediately (Kotler 1999). Reproductive behavior in squirrels may be more complicated than previously assumed. Female squirrels form reproductive plugs on their genitalia after mating. These plugs serve several purposes, including insurance of fertilization by the male squirrels. The fact that researchers documented removal of the plugs by female Fox Squirrels suggests that there may be inconsistency between the male and female reproductive strategies. Removing the plug may be beneficial to the female, allowing more copulations and a greater chance of fertilization and reproductive success (Koprowski 1992). Fox Squirrels exhibit several other general behaviors. They tend to be more diurnal than their crepuscular squirrel relatives. Also, when threatened by predators, squirrels often elicit an alarm call that consists of a harsh chatter accompanied by frantic fluttering of the tail. Finally, Fox Squirrels rarely engage in territorial disputes, and their home ranges often overlap, with several squirrels often living in the same tree or nest. Habitat Fox Squirrels appear to favor stands of tall hardwood trees (Woods, Jr., 1980) that are adjacent to open country. In Wisconsin, the squirrels occur commonly in deciduous and mixed deciduous forest, and are uncommon in conifer-dominated landscapes. Despite their occurrence in forests, the squirrels can be found in agricultural areas that have close access to woods that provide food sources. Recent research found that Fox Squirrels are more likely to be found near the forest edge than Gray Squirrels (Derge and Yahner 2000). Tree dens and leaf nests are two types of shelter that are used by Fox Squirrels during winter months. Habitat associated with each type varies. Leaf nests usually are used in more open woodlands that lack large trees with hollow trunks. The nests can vary in height from 10 feet to treetop level. They are made up of sticks and leaves from the nest tree itself. When leaves are dampened by rain, they form a weatherproof insulation for squirrels inhabiting the nest (Allen 1963). Tree dens are an important aspect of squirrel habitat in woodlands with many large and hollow trees. Squirrels usually excavate small holes formed from broken off limbs; however, they can also take advantage of secondary nesting options such as abandoned woodpecker holes and rotted wood. Tree dens provide a more effective insulation to extreme weather than do leaf nests (Allen 1963). Recent research shows that Fox Squirrels select den sites that minimize heat loss and also prevent predation by raccoons (Robb et al. 1996). Economic Importance for Humans Positive Squirrel hunting is a popular recreational activity, and it generates money for both the private and government sectors. Money from hunting licenses goes to habitat improvement and management for squirrels and other wildlife. Trapping of squirrels has become less important over the years, but Fox Squirrel pelts are still sold by trappers in many regions of the country. Negative Squirrels can cause minor crop damage to cornfields. They are often considered a pest at backyard bird feeding stations as well. Conservation Eastern Fox Squirrels are common throughout most of their range, and have not showed evidence of population decline. Their management remains important for maintenance of hunting and trapping opportunities. References Allen, Durward L. Michigan Fox Squirrel Management. Game Division Department of Conservation, Lansing, MI, 1963. Burt, William Henry. A Field Guide to the Mammals of North America North of Mexico. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, 1976. Derge, Katharine L; and Richard H. Yahner. 2000. Ecology of sympatric fox Squirrels (Sciurus niger) and gray squirrels (S. carolinensis) at forest-farmland interfaces of Pennsylvania. American Midland Naturalist 143(2): 355-69. Georgia Wildlife Website; Mammal Fact Sheet. Mammals: Sciurus niger. http://museum.nhm.uga.edu/gawildlife/mammals/rodentia/sciuridae/sniger.html Gurnell, John. The Natural History of Squirrels. Facts On File Publications, New York, 1987. Harnishfeger, R.L., J.L. Roseberry, and W.D. Klimstra. 1978. Reproductive levels in unexploited woodlot fox squirrels. Transactions of the Illinois State Academy of Science 71:342-55. Kinkead, Eugene. Squirrel Book. E.P. Dutton Company, New York, 1980. Kotler, Burt P; Joel S. Brown; Michael Hickey. 1999. Food storability and the foraging behavior of fox squirrels (Sciurus niger). American Midland Naturalist 142(1): 77-86. Koprowski, John L. 1992. Removal of copulatory plugs by female tree squirrels. Journal of Mammalogy 73(3): 572-76. Koprowski, John L. 1993a. Alternative reproductive tactics in male eastern gray squirrels: “Making the best of a bad job.” Behavioral Ecology 4:165-71. Koprowski, John L. 1993b. Behavioral tactics, dominance, and copulatory success among male fox squirrels. Ethology, Ecology, and Evolution 5:169-76. Mammals of Texas: Online Edition. Eastern Fox Squirrel (Sciurus niger). http://www.nsrl.ttu.edu/tmot1/sciunige.htm. Robb, Joseph R; Mark S. Cramer; Allen R. Parker; Richard P. Urbanek. 1996. Use of tree cavities by fox squirrels and raccoons in Indiana. Journal of Mammalogy 77(4): 1017-27. Schmidt, Kenneth A; Joel S. Brown. 1996. Patch assessment in fox squirrels: the role of resource density, patch size, and patch boundaries. The American Naturalist 147(3): 36080. Steele, Michael A. and John L. Koprowski. North American Tree Squirrels. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, 2001. Woods, Jr., S.E. The Squirrels of Canada. National Museum of Canada, Ottawa, 1980. Reference written by Scott Loss, Biology 378 student. Edited by Christopher Yahnke. Page last updated.