Archaeology Dissertation Handbook

advertisement

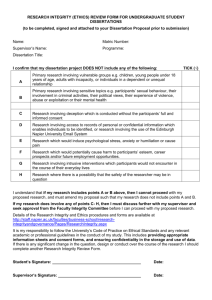

DEPARTMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGY DISSERTATION HANDBOOK Introduction This guide covers the background information you will need before you start your dissertation. It will also be of considerable help to you during the final stages of your work and contains the following main sections: SECTION THEME Section 1 Aims, requirements and getting started Section 2 Dissertation planning and the dissertation proposal Section 3 Progress monitoring and advice on your dissertation Section 4 Presentation and layout Section 5 Dissertation marking criteria Section 6 Regulations on plagiarism and collusion Appendix 1 Dissertation general timetable Appendix 2 Members of staff and areas of expertise Appendix 3 Archaeology dissertation module descriptions Appendix 4 Ethical considerations Appendix 5 Safety considerations Appendix 6 Dissertation title approval form Appendix 7 Dissertation proposal form Appendix 8 Dissertation submission form SECTION 1: AIMS AND REQUIREMENTS This section discusses the aims of dissertation work and what you are required to produce. It also provides some guidance about what makes a good dissertation, and how you might come up with a suitable dissertation topic. 1.1 AIMS The aim of the dissertation is to give you an opportunity to display your skills in tackling specific archaeological issues in some depth. You will have the chance to pursue a topic that you have found interesting. The essence of the work is that you are able to demonstrate your ability to undertake your own piece of independent research, set your own goals and keep to your working schedules. The specific intended learning outcomes are given in the module descriptions in Appendix 3. 1.2 NATURE OF STUDY Subject to available resources, there are generally no restrictions on the type of archaeological study that you can undertake. You may choose a subject area completely outside the syllabus, as long as there are available source materials. Your dissertation may be carried out within one of the thematic or period branches of the subject, or on a regional basis, or on aspects of archaeological methodology. Studies involving first-hand fieldwork data collection tend to be suitable in many cases, but comparative or critical studies based on library/archive material are equally acceptable (see section 1.5 for guidance on choosing a topic). The study must be, however, more than a mere compilation of existing information, so that you can demonstrate some independent thought. Your sources, whether of data, opinions or illustrations, must be made clear throughout the work (see Section 6 on plagiarism and collusion). 1.3 REQUIREMENTS Archaeology Single Honours students are required to produce a dissertation (ARC3000) of no more than 9,000 words (excluding bibliography, tables and appendices). Your dissertation is important as it counts for 30 credits (i.e. two papers) in the final examinations. Combined Honours students may opt to do a dissertation in either Archaeology (ARC3000) or their other discipline or a joint dissertation. History and Archaeology combined honours students may opt to do a joint dissertation (ARC3001) on a subject embracing History and Archaeology. This also has a 9,000 word limit (excluding bibliography, tables and appendices) and is valued at 30 credits. These credits can be taken from either the Archaeology or History side of your programme, by negotiation. Ancient History and Archaeology combined honours students may opt to do a joint dissertation (ARC3004) on a subject embracing Ancient History and Archaeology. This has a 10,000 word limit (excluding bibliography, tables and appendices) and is valued at 30 credits. These credits can be taken from either the Archaeology or Ancient History side of your programme, by negotiation. 2 1.4 WHAT MAKES A GOOD DISSERTATION? 1. A good problem, set in its academic context. 2. Clear statement of aims, research questions and objectives. 3. A logical research programme. 4. Clearly defined and appropriate methodology. 5. Adequate and appropriate data for the problem. 6. Adequate and appropriate data analysis. 7. Clear statement of results and your interpretation. 8. Well structured and clearly written. 9. Intellectual achievement. 10. Sound conclusions that relate to the stated aims and research questions. 11. Good presentation, including illustrations as appropriate 1.5 GETTING STARTED Your dissertation should be framed within a broad area of study (a research topic). This topic may relate to a particular archaeological period, a particular geographical region or a particular type of archaeological site. Alternatively, it might relate to a particular theme in archaeology theory and interpretation or an area of archaeological methodology. Within this you should identify a research problem, this is a more specific, smaller issue within the general topic. The research problem should lead to the identification of research questions. These are specific questions that you ask in relation to your problem, i.e. how you approach the problem. For example: Research topic: Prehistoric stone circles. Research problem: Variation in the character of Scottish stone circles. Research questions that might arise from this include: In what ways do Scottish stone circles vary in terms of design? Is this variation related to date of construction? Is the variation related to different functions of the monuments? Is there any relationship between circle type and the surrounding area, in terms of the ritual landscape and natural topography? How does the variation in Scottish circle design compare with variation in other regions of the British Isles? What are the problems associated with answering such questions, in terms of methodology and the limitations of the evidence? In choosing a topic you need to consider: Is it interesting? Can the topic retain your interest and motivation? Is it practical? Is there enough time available for data collection? What other commitments (work, holidays) do you need to consider? Do you need permission for access to field sites or other sources of data? Do you need assistance in the field? Is the time required for analysis reasonable and realistic? Does the library have adequate literature on the subject area? Can I get to the study area from a base in Exeter? 3 Is it financially viable? Can you afford the transport, materials and inter-library loans (if appropriate)? N.B. You may apply to the Department’s Fox-Lawrence Fund for financial assistance related to your dissertation work. What equipment do I need? Does the department have it? Will it be available? (applies to both field and laboratory equipment) Safety? Are there any risks that need to be identified in field or laboratory work (if relevant)? We are unlikely to approve topics that could put students in any danger. If your proposed field of study involves anything hazardous, this must be discussed with the departmental safety officer before your topic is approved (see Appendix 5). Identifying a research problem You should choose a dissertation which reflects your interest in the subject and which attempts to address current debates in archaeology. You may want to choose a field of study that allows you to develop particular skills that will be of use to you in the future. Ideas can often be gained from reading recent journal issues (e.g. major period journals, Journal of Archaeological Science, Antiquity etc.) and from your second year modules. Perhaps the most difficult part of the dissertation process is identifying a problem to address. Once you have identified a suitable research topic, you need to decide what particular aspect of the topic you are going to investigate. This requires you to be familiar with what other research has already been done in the field, and what is of interest. Your project must also be set in the context of this existing research. This means that you need to carry out research in the library, checking journals, abstracts and databases before finalising your topic or starting practical work. Below are some tips for generating research ideas: 1. Follow up an idea that arose in a lecture. 2. Read articles or books on a topic that interests you. 3. Be on the lookout for ideas in the media: newspapers, radio, television etc. 4. Talk to organisations or individuals working in your area. 5. Think about your own outside interests and skills: can they generate a research topic? 6. Have you decided on a future career path? Can the dissertation be made relevant to that? Parsons & Knight (1995) outline a series of ways in which a research problem can be identified: 1. Nobody has investigated this topic…I will! 2. Bloggs (1990) investigated this topic and questioned the role of X. I’ll investigate the role of Y. 4 3. Bloggs (1990) investigated this topic at site X and found that…. I’ll investigate whether or not the same is true at site Y. 4. Bloggs (1990) investigated this topic and suggested that X was controlled by Y and Z. I’ll investigate whether or not this is the case. 5. Bloggs (1990) investigated this topic and found that…Have things changed since then? I’ll repeat the study and compare results…if things are different/the same, I'll explain why? 6. Bloggs (1990) investigated this topic using method X. I’ll see if method Y gives different results…compare with X results and explain differences. Research questions Specific research questions should be directly related to, and arise logically from, the research problem you are addressing. 1. Pursue questions that look as though they will have interesting answers or solve a particular problem. 2. Questions are usually good if you can suggest or predict what answers they may have (i.e. set up hypotheses) and what the implications of these answers are. 3. The best questions are relatively easy to answer but make significant steps forward in the investigation! Research questions can be stated in terms of questions or experimental hypotheses. For example: Is X related to Y? (research question), or X is related to Y (experimental hypothesis). Perhaps one of the most important issues to take note of is the difference between a casual and a causal relationship. Just because two factors may appear to be linked (i.e. statistically, or by observation) it does not necessarily mean that there is a cause-and-effect relationship. It is up to you to interpret the results of your observations and to devise research strategies by which you might establish causality. Establishing your research aims You will need to have a clear idea what your research aims are for your dissertation proposal. The aims of your dissertation can be put forward in terms of the research problem you have identified and the questions you are going to ask whilst researching that problem. A clear statement of research questions is important because these statements determine the direction of your project; the type of information you require to answer the questions determines the methods you need to use and the way you analyse the data collected. In your conclusions you should aim to address and reflect upon your original research problem and questions. The research questions should ideally be capable of leading to conclusions. ‘Woolly’ research questions often result in overly descriptive rambling discussions, that fail to reach any firm conclusions! 5 1.6 RECOMMENDED READING ON RESEARCH AND DISSERTATION WRITING Baxter, L., Hughes, C. and Tight, M. 1996: How to Research. Buckingham: Open University Press. Bell, J. 1993: Doing your Research Project. Buckingham: Open University Press. Creswell, J.W. 1994: Research Design: Qualitative and Quantitative Methods. London: Sage. Flick, U. 1998: An Introduction to Qualitative Research. London: Sage. O’Connor, M. and Woodford, F.P. 1975: Writing Scientific Papers in English. Oxford: Association of Scientific Publishers. Parsons, T. and Knight, P.G. 1995: How to do your Dissertation in Geography and Related Disciplines. London: Chapman & Hall. Rudestam, K.E. and Newton, R.R. 1992: Surviving your Dissertation. London: Sage. 6 SECTION 2: DISSERTATION PLANNING AND THE PROPOSAL The Dissertation module is assessed by two separate pieces of written work: i. The Literature Survey and Dissertation Plan – 10% of the module mark ii. The Dissertation itself – 90% of the module mark 2.1 STAGE I This section explains what the procedures are for submitting your dissertation proposal, the assignment of a dissertation supervisor and producing the Literature Survey and Dissertation Plan. The timetable for this preliminary stage is as follows: Late February/early March: Dissertation briefing meeting March: general discussion with potential dissertation supervisors about your proposed field of study. You can consult with as many people as you like at this early stage (Appendix 2 lists areas of staff expertise to help you to decide who to go and see). If you really have no idea where to start, see your personal tutor. Combined Honours students proposing to do a Joint Dissertation must consult with staff in both disciplines. When you feel satisfied with a particular field of study, fill in a Dissertation Proposal Form (Appendix 7) and take it to the member of staff within whose area of expertise the topic falls for his/her comment and signature. You should not assume that your proposal will necessarily be accepted as it stands; it may be referred back to you for emendation, so do not leave this until the last minute. Friday 6 May 2011- deadline for submission of the signed Dissertation Proposal Form to the Departmental Office. You will be assigned a Supervisor who will normally be the person who agreed your topic. After exams: start work on your Literature Survey and Dissertation Plan. Early October: brief meeting with your Supervisor to report progress. Thursday 27 October 2011 submit the Literature Survey and Dissertation Plan by 4pm to the College office, Queens Building. Early December: individual supervision to return marked Literature Survey and Dissertation Plan to discuss issues arising from it and progress in general. 2.2 STAGE II Researching and writing the Dissertation (for further detail see Appendix 1). January & February: individual or group consultations with the supervisor. End of February: if the topic submitted has been changed, fill in a Dissertation Title Approval Form (Appendix 6), get your supervisor to sign it and submit it to the 7 Departmental Office. March (before the end of term): final consultation with your supervisor. Thursday 3 May 2012: hand in your Dissertation to the College Office, Queens Building 2.3 PILOT STUDIES AND ACCESS TO INFORMATION It is important that, where necessary, you seek prior permission for access to land, archives or other sources of data before the fieldwork or research is undertaken (see Appendix 4). A standard letter will be made available on request to explain that you are carrying out work that is an essential part of your degree course and not related to any official investigation on the part of the University. If relevant to the type of work you will be undertaking, it may be a good idea to carry out a preliminary pilot project. This might involve carrying out a scaled-down version of your methodology (field work, archive or laboratory work) in order to: 1. Identify potential bottlenecks in the project, e.g. time taken to collect or analyse data. 2. Determine whether or not your data collection technique is viable/feasible. 3. Determine how detailed your data have to be. 4. How much material (e.g. sample size) you require 5. How long the processing and analysis of sample/data takes Carrying out a pilot project can be an effective means of determining the viability of a project. It can help you to avoid one of the worst problems that may come to light only after you have collected your data, and begin to analyse and interpret it: 'If only I had recorded/asked/collected X, then I could have carried out Y analysis, and answered question Z.' Often it is too late to rectify this situation. 2.4 CHANGE OF TOPIC Should you decide, during work on your Literature Survey and Dissertation Plan, that you wish to change research direction and focus on a topic different to that of the original, agreed, proposal, you must contact the Dissertation Co-ordinator immediately. A change of topic will be allowed, subject to the proposed Supervisor’s approval of the revised topic; in this case, a new Dissertation Proposal Form (Appendix 7) will be filled in by the student, signed by the Supervisor and submitted to the Departmental Office. Remember that during the Summer Vacation staff may well be away from the University for extended periods on fieldwork, so do not leave this until the last minute – in any case, no extension will normally be allowed on the literature survey submission date. 2.4.1 SUBMITTING A FINAL TITLE The latest you can submit a final title for your dissertation is the end of February of your final year. At this stage you should already be well into the writing stage and have a good understanding of the structure of your dissertation. You will need to fill in a Dissertation Title Approval Form (Appendix 6) and get your supervisor to sign it. Hand the completed form to the Departmental Office. 8 SECTION 3: PROGRESS MONITORING AND ADVICE ON YOUR DISSERTATION 3.1 WHAT CAN I EXPECT FROM MY DISSERTATION SUPERVISOR(S)? The dissertation is your own piece of independent research. You should, therefore, expect to undertake the necessary activities - thinking and doing - independently. Your dissertation supervisor's principal responsibility is to monitor your progress and advise. 1. The dissertation supervisor, or other staff members, can offer technical advice on the dissertation, e.g. appropriate methodology, logistics, resources, ways of illustrating. 2. On the basis of your verbal progress reports during meetings, your dissertation supervisor will give advice regarding your progress towards your objectives. 3. On the basis of supervision meetings with you, your supervisor will alert the dissertation co-ordinator regarding any unsatisfactory progress 4. When required and requested, your dissertation supervisor will answer direct and specific questions of a technical nature (e.g. is this analytical method appropriate?) - this direction may also be obtained from other staff where appropriate. 5. Your dissertation supervisor, along with any other member of staff you care to consult, can offer you technical advice at any time during the third year, but this will not include reading any draft chapters. Your supervisor will, however, comment on the proposed structure of the dissertation in plan and on drafts of the contents page. You cannot expect your Dissertation Supervisor to: 1. Tell you what to do next. 2. Tell you what to do with your data. 3. Think of new projects for you. 4. Read draft copies of dissertation materials. 3.2 WHAT WILL YOUR DISSERTATION SUPERVISOR EXPECT FROM YOU? That you attend meetings You should attend meetings with your supervisor to discuss your progress and general matters relating to dissertation work. The general timetable of such meetings is presented in appendix 1. These meetings will be advertised on your supervisor’s notice board. Since this is an independent piece of work you must take responsibility for its completion and this includes attending the meetings. Remember to take notes during these sessions (particularly of bibliographic information), so that you do not need to chase reference details later. 9 NB. You are strongly advised to be pro-active in maximising opportunities for seeking advice. You may make appointments to see your supervisor at other times, during their office hours. That you make progress on your dissertation You should have made substantial progress on your literature survey and dissertation plan during the long summer vacation. This period should have been used to carry out reading, collect your thoughts and organise the structure of your work and how you will go about obtaining the rest of the information you need. If your dissertation involves fieldwork, the summer vacation may be a good time to carry out the work (you may have the spare time and the weather is more favourable), but you should plan fieldwork for the most appropriate time (e.g. you may prefer the winter, because the vegetation will have died down). During the Autumn and Winter of your final year, you should ideally be completing the collection of your data and processing and analysing it. If you are using a computer and have any difficulties, you can consult the duty programmers in the I.T. Services. That you keep your supervisor informed of any change in direction/topic If you decide to change research direction, and focus on a topic different to that of the original dissertation proposal, you must contact your assigned dissertation supervisor and the dissertation co-ordinator as soon as possible. This is so that you can be assigned a dissertation supervisor appropriate to your chosen area of research. You will be expected to submit a new dissertation proposal to the new dissertation supervisor. NB. Remember to keep back-up copies of your dissertation and the data you have collected at all times! Back up your data both during and after every session on the computer. 3.3 WHEN MUST I SUBMIT MY WORK? Literature Survey and Dissertation Plan (2 copies) must be must be handed in to the College Office by 4pm on 27 October 2011. Dissertation (2 copies, including a dissertation submission form and BART cover sheet ) must be handed in to the College Office by 4pm, on the Thursday of the first week of summer term in your final year. Failure to do this will be dealt with severely: the Board of Examiners will normally apply a penalty for late submission and the late assignment will receive a maximum mark of 40%. If the work has still not been submitted after two weeks, the work will not be marked at all and you will receive a mark of zero. It is the student’s own responsibility to bring any potentially extenuating circumstances to the attention of the dissertation supervisor and provide appropriate supporting documentation. 10 SECTION 4: PRESENTATION AND LAYOUT This chapter provides information about how to organise and set out your dissertation report, as well as when and how to submit it. Failure to present a dissertation according to these recommendations may result in its rejection or downgrading. 4.1 WORD LIMIT AND PAGE FORMAT Your literature survey and dissertation plan should not exceed 1,000 words excluding bibliography. Your dissertation should not exceed 9,000 words (10,000 for Ancient History/Archaeology dissertation), excluding appendices, tables and bibliography. Both elements must be word-processed with 1.5 line spacing on single sides of A4 and all pages must be clearly numbered. For the dissertation, care must be taken to provide wide margins (necessary for binding). Leave approximately 4cm on the left margin and 3cm on the right. You will bear the costs of production (illustrations, typing, paper, outer cover, binding). 4.2 STRUCTURE AND CONTENTS OF THE LITERATURE SURVEY & DISSERTATION PLAN 4.2.1 The literature survey The first stage in researching your topic will involve you in reading around your subject in order to familiarise yourself with the relevant contextual information. You need to find out what is already known and what is not known about your proposed field of study and to investigate potential data sources. Depending on the topic of the dissertation, this may involve a topographical survey in order to get to know and help refine your study area a methodological study designed to acquaint you with appropriate approaches to your material – those that others have found to work (or not) and those which it is worth trying a review of similar work in a different geographical/environmental/historical context Make use of search engines and consolidated bibliographies; follow up references and bibliography in general works; trawl through regional/topic/period-based periodicals. You do not, at this stage, have to read in detail everything to which you make reference; what is required is that you show an awareness of its potential. Make use of tables of contents, abstracts, chapter and section heads and indexes. This review should be written in continuous prose, using Harvard referencing as normal. 4.2.2 The dissertation plan This is a reasoned outline of how you intend to proceed with your work on the dissertation – what you intend to do, the themes you intend to pursue, the resources you will use, how you intend to structure the work and an outline timetable for doing it. It should include reference to: your research question – overall aims and objectives the ways in which you plan to answer your question. You should refer to: 11 further background work required primary sources to be studied (you should have made at least a preliminary assessment of these) fieldwork to be undertaken any practical issues such as those relating to finance, timetabling, health and safety, ethics This plan may be produced in report form, using bullet points and tables as appropriate. 4.2.3 Bibliography The bibliography should include both material which you have already read during the preparation of your survey, and relevant-sounding material which you have learnt about and intend to pursue. It should include appropriate web-based material as well as the printed word. The bibliography must be presented in Harvard style according to our normal conventions. Advice on referencing of unfamiliar primary source material should be sought from your supervisor. 4.2.4 Word limit LITERATURE SURVEY AND DISSERTATION PLAN: word limit, 1000 words. BIBLIOGRAPHY: there is no word limit to the bibliography. 4.3 STRUCTURE AND CONTENTS OF THE DISSERTATION The dissertation should be arranged as follows: 1. Title page (which must include your student registration number) 2. An abstract 3. A contents page (to include chapter headings and other sub-divisions of the typescript) 4. Lists of illustrations (line drawings and photographs) 5. List of tables (if appropriate) 6. List of appendices (if appropriate) 7. Acknowledgements 8. Main body of the dissertation – your various chapters (give them headings and numbers) 9. Appendices (covering detailed material and data, elaboration of methods and techniques) 10. Bibliography There is no single approved structure for a dissertation. There is, however, such a thing as a clearly and logically structured report. The dissertation should, therefore, include 12 components 1-8 and 10 (listed above) in that particular order. The structure must be clear and logical, include an early statement of the research aims, previous research, methods, results, analysis of results and discussion, and lead to logical conclusions. 4.3.1 Chapters, headings and subheadings Within individual chapters (which must be numbered), you may wish to use sub-headings. These should be used in a logical and consistent manner. This will help the reader (i.e. examiner) navigate his/her way around the dissertation. There is a balance between over and under dividing the dissertation up into sections. Too many sections and subsections may break up the flow and make the dissertation appear “bitty” or fragmented. Too few sections or subsections will make it more difficult for the reader to work out where they are and where they are going. Organising the report into sections will also help you to organise and decide where to place various bits of information. It is a good idea to include a brief statement of what each chapter is about at the beginning to help the reader work out where they are going. A short summary at the end of each chapter can be equally valuable in helping navigation and general flow, e.g.: This chapter discusses the results of….(at the start) This chapter has discussed the…and leads onto….(at the end) You can number the sections and subsections in order to help navigation. This system will enable you to refer the reader to particular sections in the text (e.g. see Section 4.3). 4.3.2 Contents It is a good idea to number chapters and sub-divisions. You should list all the chapter headings and subdivisions and list the page number at which each of them starts. 4.3.3 Abstract The abstract should be a very concise summary of the work. It should give the reader a clear understanding of the nature of the work, its principal content and conclusions. A common mistake is to treat the abstract as a brief introduction, which is not its purpose. The abstract need not be any longer than half a side of A4, but should certainly not be longer than one side. 4.3.4 Figures and tables Figures include all maps, line drawings, and photographs. Tables are considered and numbered separately from figures. All figures and tables must be numbered. Tables are numbered separately from figures. For example, using the numerical system, Table 4.1 would be the first table in chapter 4; Figure 4.1 would be the first figure in chapter 4. All tables and figures should be closely integrated with, and referred to, in the text. It is not sufficient simply to put text and illustrations side by side hoping that the reader/examiner will make the connection. Illustrations must be truly part of the dissertation, not merely decorative additions. 13 Maps and Line Drawings Maps and line drawings should normally be reduced to fit on an A4 page or, exceptionally, a size suitable for folding to A4. Maps and diagrams may either be drawn by hand or computer generated, but good-quality photocopies of published material are acceptable. Maps and diagrams should have adequate scales and keys. Each map or diagram should have a figure number and caption outside the frame. The source of the illustration or information must also be given (and listed fully in the references); e.g.: Figure 1.1: A map showing the location of Scottish stone circles (source: Burl 1976, fig.19) Photographs Photographs, digitised images and photocopies (colour or monochrome) may also be used if required (should fit A4 format). Mounting of photographs and other illustrations should be on normal weight paper. Remember to include a scale. Photographs must be given a caption and a figure number and be credited, e.g.: Figure 1.1: Balnuaran of Clava, near Inverness (photo by author) Separate lists of figures and tables should be included in the contents. NB. Ensure that all your figures are clear and of sufficient size and resolution to be able to make out text and important features, i.e. not small, fuzzy, and difficult to make out. Warning: computer scanning may seem a good method of reproduction, but unless it is carried out at very high resolution it often gives poor results (high quality, digital photocopying will probably work better). Tables Tables should be designed to make the information they contain clear. Tables should all be given a title. If you have many tables of data, it may be advisable to put them in an appendix. Your supervisor will be able to advise on this. 4.4 REFERENCING AND THE BIBLIOGRAPHY The Harvard system must be employed consistently throughout the work, and high standards of accuracy are expected. For guidance on how the Harvard system works, see the Undergraduate Handbook. If in doubt over how to reference a particular source, ask your supervisor for advice. You are asked to pay particular attention to the system of references and bibliography. Many dissertations fail to reach adequate standards in these aspects and many otherwise good pieces of work are marked down as a result. In-text referencing is often inadequate. 14 Quoting Note that if you quote material in your text you should give the page numbers in the reference. You should also place quotation marks around the quoted section. 4.5 CONVENTIONS ON MEASUREMENTS All measurements, in text and illustrations, must be in metric, though it may be useful to give imperial equivalents when discussing, for example, medieval buildings. 4.6 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Due acknowledgement should be made to all those who have assisted in the compilation of the dissertation. If unpublished results are being used or referred to, it is particularly important to make sure that the excavator or other specialist is prepared to allow such citation. A breach of common practice in this matter might be viewed seriously by the offended party and would certainly lay you open to a charge of plagiarism. The sources of illustrative material must be indicated. 4.7 CHECKING YOUR WORK Before submission, the whole text of your dissertation should be checked carefully for typing errors and consistency of presentation. You should also check that you have listed all your references and that all tables and figures are clearly presented and referenced. 4.8 BINDING This must follow a standard prescribed by the Department. The dissertation should be bound using soft thermal binding with a clear (see-through) cover, so that your title page is visible. This can be done in the Guild Print Unit. 15 SECTION 5: DISSERTATION MARKING CRITERIA Below, the criteria used in the marking of the Literature Survey and Dissertation Plan and of the Dissertation itself are outlined. If you bear each of these criteria in mind when writing your survey and your dissertation you will be more likely to produce a good piece of work. Ask yourself whether you have satisfied all the criteria and whether there are any areas you could improve. 5.1 THE LITERATURE SURVEY AND DISSERTATION PLAN o Has the candidate identified an appropriate topic for investigation? o Has the candidate familiarised him/herself with relevant contextual information? o Is the candidate aware of the relevant source materials? o Has the candidate devised an appropriate programme of investigation? o Is the candidate aware of the potential problems and pitfalls which (s)he may encounter? o Has the candidate demonstrated appropriate bibliographic skills? 5.2 THE DISSERTATION 5.2.1 Content o Has the candidate formulated a coherent topic for investigation? o Has the candidate acquired a suitably detailed knowledge of the subject area under investigation? Is this knowledge placed in its wider context? o Do they know and use the correct methodologies, terms and conventions for their subject area? o Have they demonstrated an ability to analyse critically and deploy primary archaeological (and historical, where appropriate) data? Are the data placed in its wider context? o Is the content appropriate to the title and the research questions outlined in the introduction? o Is the work well structured and does it lead to a suitable conclusion? o Has the candidate demonstrated appropriate bibliographic and referencing skills? o Are there appropriate accompanying illustrations? Are these suitably integrated with the text? 16 o Does the candidate demonstrate independent thought? (at the upper end of the mark range) o Is the abstract an accurate and clear statement of the content of the dissertation? 5.2.2 Presentation o Is the work neatly presented according to the guidelines laid down in this handbook (e.g. binding, title page, contents, lists of tables and figures, acknowledgements, appendices, margins, spacings etc)? o Are the references and bibliography laid out in Harvard style, following the format laid down in the Undergraduate Handbook? o Are the illustrations well and suitably presented according to the guidelines given in this handbook? o Has the candidate demonstrated suitable writing skills (i.e. is the work in a suitable academic style; is the grammar, spelling and punctuation correct; is the writing suitably concise and precise)? o Has the work been well proof read (i.e. how many typographic errors etc. remain)? 17 SECTION 6: REGULATIONS ON PLAGIARISM AND COLLUSION 6.1 PLAGIARISM You are reminded that the failure to reference the published and unpublished work of other academics may result in a charge of plagiarism. This is effectively passing off someone else’s thoughts, ideas, writings and work as your own. People can be guilty of plagiarism if they copy, without proper attribution (i.e. acknowledging by referencing the author appropriately), from a book, scholarly article, lecture handout, electronically-stored text or another student’s work. In this context ‘copying’ does not just mean word for word copying. It also includes straight paraphrasing, sentence by sentence, of a source material. 6.2 COLLUSION Unauthorised collusion, is aiding or attempting to aid or obtaining or attempting to obtain aid from another candidate or any other person. In the case of a dissertation project this might include obtaining unauthorised help with preparation of the report or with field/laboratory work. Note the stress is on unauthorised. It is recognised that an important skill developed during the course of your dissertation research is the forging of contacts with various people within and outside the Archaeology Department. Some of these contacts may offer you practical assistance. If you are in any doubt you should seek guidance and authorisation from your Dissertation Supervisor on what may be deemed inappropriate aid. All assistance must be acknowledged. N.B. The dissertation forms a major part of your degree and any breach of University Regulations will be considered very serious. Please note that both plagiarism and collusion are very serious offences, which could result in the outright failure of your degree. Further details of definitions and procedures concerning plagiarism and collusion can be on the College intranet http://intranet.exeter.ac.uk/humanities/ug/handbook/ 18 APPENDIX 1: DISSERTATION GENERAL TIMETABLE N.B. You can make appointments to see your supervisor at other times, if needed. When? What? 2 March-April (stage 2) Meet with prospective dissertation supervisors to discuss ideas (book appointments with them) 2 By Friday, first week of the summer term (stage 2) Get approval of your topic (if necessary, revise and resubmit until approval given). Submit a dissertation proposal form signed by both your potential supervisor and yourself. 2 Once approval is obtained Start work on your literature survey and dissertation plan. Summer vacation Work on your literature survey and dissertation plan. Do background reading, visit sites, do pilot studies (if appropriate). 3 Early/mid October Meet with your supervisor to discuss progress. 3 27 October 2011 Deadline for literature survey and dissertation plan. 3 Late November/ early December Meeting with supervisor for feedback on your literature survey and dissertation plan. Discussion of general issues pertinent to dissertations. 3 January Meeting with supervisor. 3 February Meeting with supervisor. You should finalise your dissertation title and, if this has been changed from the title submitted on your dissertation proposal form, hand in a title approval form (Appendix 6) by the end of the month. You should now be able to describe the content and structure of your work in detail. Provisional conclusions should be emerging. Ideally, you should be writing a first draft by now and you should have made a start on illustrations. 3 March Meeting with supervisor before the end of term. Do not assume that your supervisor will be available for consultation during the Easter vacation 3 Thursday first week, summer term (by 4 pm) Hand in dissertation N.B. leave plenty of spare time – malfunctioning computers, printers etc. will not be taken as a valid excuse for being late. 19 APPENDIX 2: MEMBERS OF STAFF AND AREAS OF EXPERTISE * Below is a guide to the general expertise of potential dissertation supervisors. See the departmental web pages for more details. Bruce Bradley Prehistory, lithics, experimental archaeology Oliver Creighton Castles, medieval buildings, later medieval archaeology, landscape archaeology Anthony Harding Neolithic and Bronze Age in Europe Linda Hurcombe Prehistory, material culture, lithics, experimental archaeology Jose Iriarte South American prehistory, archaeobotany, environmental archaeology Gill Juleff Archaeometallurgy, experimental archaeology, South-East Asia Chris Knüsel Bioarchaeology, osteoarchaeology, forensic archaeology Marisa Lazzari South American prehistory, material culture and cultural landscape studies, social archaeology Robert Morkot The archaeology of ancient Egypt and North Africa Ioana Oltean Roman mid-lower Danube provinces, IA/Roman settlement patterns and landscapes, GIS, aerial archaeology Alan Outram Hunter-gatherers, palaeoeconomics, environmental archaeology, scientific analytical techniques, industrial archaeology Stephen Rippon Late Roman and early medieval Britain, landscape archaeology, maps, field techniques Robert Van de Noort Wetland archaeology and conservation, GIS, remote sensing, the Iron Age Dissertation coordinator: Dr Ioana Oltean (i.a.oltean@exeter.ac.uk; Laver, room 305) Ethics: Dr Marisa Lazzari (m.lazzari@exeter.ac.uk; Laver, room 304) Safety: Dr Gill Juleff (g.juleff@exeter.ac.uk; Laver, room 307) * For up-to-date staff administrative responsibilities and study leave arrangements please check with the Departmental Office. 20 APPENDIX 3: MODULE DESCRIPTIONS Module Code: ARC 3000 Module Title: ARCHAEOLOGICAL DISSERTATION Credit Value: 30 ECTS Value: 15 Pre-requisites: 60 archaeology credits at levels 1 and 2 Co-requisites: Duration of module: Two terms Total Student Study Time: 300 hours Module level: Level 3 AIMS: The module will develop the ability to define a field of enquiry, undertake a sustained period of research into it and produce a dissertation upon it. It will encourage the application of knowledge, principles, skills of enquiry and (where appropriate) illustrative skills. It will develop the ability critically to evaluate the issues relating to the subject area. INTENDED LEARNING OUTCOMES: students will be enabled to Knowledge and understanding: o acquire a detailed knowledge of the subject area under investigation o know the chronological and methodological frameworks of the research area o know and deploy terms and conventions in their correct contexts Subject-specific skills: o critically analyse and deploy primary archaeological data o prepare and deploy appropriate illustrative material Core Academic skills: o ability to undertake a sustained enquiry o deploy bibliographical skills o evaluate conflicting opinions Personal and Key skills: o devise, implement and keep to a work schedule o produce a substantial written report, using appropriate illustrations TEACHING AND LEARNING METHODS: Introductory meeting; 5 meetings with supervisor; self-directed study. ASSIGNMENTS: o Literature survey and dissertation plan; designed to focus on the context of the dissertation and the ways in which the topic will be developed. o Dissertation: designed to focus on an area of contention or apply knowledge and principles to a chosen field of enquiry o Periodic verbal reports at meetings with supervisor. ASSESSMENTS: Literature survey and dissertation plan; 1,000 words (excluding bibliography). 10% of module mark. 9,000-word max dissertation (word limit excludes bibliography and figure captions.) 90% of module mark. SYLLABUS PLAN: o Introduction to dissertations (Term 2 of stage 2). Dissertation handbook issued. o Consultation with potential supervisors to define topic (March, stage 2) o Early October Level 3: individual meeting with supervisors to report progress made during vacation o discussion of preliminary bibliography. o 5 supervision meetings INDICATIVE BASIC READING LIST: Baxter, L., Hughes, C. & Tight, M. 1996: How to research. Buckingham: Open University Press. Bell, J. 1993: Doing your research project. Buckingham: Open University Press. Creswell, J.W. 1994: Research design: qualitative and quantitative methods. London: Sage. Flick, U. 1998: An introduction to qualitative research. London: Sage. Parsons, T. & Knight, P.G. 1995: How to do your dissertation in geography and related disciplines. London: Chapman & Hall. Rudestam, K.E. & Newton, R.R. 1992: Surviving your dissertation. London: Sage. 21 Module Code: ARC 3001 Module level: Level 3 Dissertation Module Title: JOINT HISTORY AND ARCHAEOLOGY DISSERTATION Credit Value: 30 ECTS Value: 15 Pre-requisites: 90 credits of History and Archaeology Co-requisites: Duration of module: Two terms Total Student Study Time: 300 hours AIMS: The module will develop the ability to define a field of enquiry drawing upon the two disciplines of History and Archaeology, undertake a sustained period of research into it and produce a dissertation upon it. It will encourage the application of knowledge, principles, skills of enquiry and (where appropriate) illustrative skills. It will develop the ability critically to evaluate the issues relating to the chosen topic. INTENDED LEARNING OUTCOMES: students will be enabled to Knowledge and understanding: o acquire a detailed knowledge of the subject area under investigation o know the chronological and methodological frameworks of the research area o know and deploy terms and conventions in their correct contexts o understand the relative contributions of History and Archaeology and their relationship within the field of enquiry. Subject-specific skills: o critically analyse and deploy primary historical and archaeological data o prepare and deploy appropriate illustrative material Core Academic skills: o undertake a sustained enquiry o deploy bibliographical skills o evaluate conflicting opinions Personal and Key skills: o devise, implement and keep to a work schedule o produce a substantial written report, using appropriate derived or original illustrations TEACHING AND LEARNING METHODS: Introductory meeting; 5 meetings with supervisors; self-directed study. ASSIGNMENTS: o Literature survey and dissertation plan; designed to focus on the context of the dissertation and the ways in which the topic will be developed. o Dissertation: designed to focus on an area of contention or apply knowledge and principles to a chosen field of enquiry o Present periodic verbal reports at meetings with supervisors. ASSESSMENTS: Literature survey and dissertation plan; 1,000 words (excluding bibliography). 10% of module mark. 9,000-word max dissertation (word limit excludes bibliography and figure captions.) 90% of module mark. SYLLABUS PLAN: o Introduction to dissertations (Term 2 of stage 2). Dissertation handbook issued. o Consultation with potential supervisors to define topic (March, stage 2) o Early October Level 3: individual meeting with supervisors to report progress made during vacation o discussion of preliminary bibliography. o 5 supervision meetings INDICATIVE BASIC READING LIST: Baxter, L., Hughes, C. & Tight, M. 1996: How to research. Buckingham: Open University Press. Bell, J. 1993: Doing your research project. Buckingham: Open University Press. Creswell, J.W. 1994: Research design: qualitative and quantitative methods. London: Sage. Flick, U. 1998: An introduction to qualitative research. London: Sage. Parsons, T. & Knight, P.G. 1995: How to do your dissertation in geography and related disciplines. London: Chapman & Hall. Rudestam, K.E. & Newton, R.R. 1992: Surviving your dissertation. London: Sage. 22 Module Code: ARC 3004 Module level: Level 3 Dissertation Module Title: JOINT ANCIENT HISTORY AND ARCHAEOLOGY DISSERTATION Credit Value: 30 ECTS Value: 15 Pre-requisites: 90 credits of Ancient History and Archaeology Co-requisites: Duration of module: Two terms Total Student Study Time: 300 hours AIMS: The module will develop the ability to define a field of enquiry drawing upon the two disciplines of Ancient History and Archaeology, undertake a sustained period of research into it and produce a dissertation upon it. It will encourage the application of knowledge, principles, skills of enquiry and (where appropriate) illustrative skills. It will develop the ability critically to evaluate the issues relating to the chosen topic. INTENDED LEARNING OUTCOMES: students will be enabled to Knowledge and understanding: o acquire a detailed knowledge of the subject area under investigation o know the chronological and methodological frameworks of the research area o know and deploy terms and conventions in their correct contexts o understand the relative contributions of Ancient History and Archaeology and their relationship within the field of enquiry. Subject-specific skills: o critically analyse and deploy primary historical and archaeological data o prepare and deploy appropriate illustrative material Core Academic skills: o undertake a sustained enquiry o deploy bibliographical skills o evaluate conflicting opinions Personal and Key skills: o devise, implement and keep to a work schedule o produce a substantial written report, using appropriate derived or original illustrations TEACHING AND LEARNING METHODS: Introductory meeting; 5 meetings with supervisors; self-directed study. ASSIGNMENTS: o Literature survey and dissertation plan; designed to focus on the context of the dissertation and the ways in which the topic will be developed. o Dissertation: designed to focus on an area of contention or apply knowledge and principles to a chosen field of enquiry o Present periodic verbal reports at meetings with supervisors. ASSESSMENTS: Literature survey and dissertation plan; 1,000 words (excluding bibliography). 10% of module mark. 10,000-word max dissertation (word limit excludes bibliography and figure captions.) 90% of module mark. SYLLABUS PLAN: o Introduction to dissertations (Term 2 of stage 2). Dissertation handbook issued. o Consultation with potential supervisors to define topic (March, stage 2) o Early October Level 3: individual meeting with supervisors to report progress made during vacation o discussion of preliminary bibliography. o 5 supervision meetings INDICATIVE BASIC READING LIST: Baxter, L., Hughes, C. & Tight, M. 1996: How to research. Buckingham: Open University Press. Bell, J. 1993: Doing your research project. Buckingham: Open University Press. Creswell, J.W. 1994: Research design: qualitative and quantitative methods. London: Sage. Flick, U. 1998: An introduction to qualitative research. London: Sage. Parsons, T. & Knight, P.G. 1995: How to do your dissertation in geography and related disciplines. London: Chapman & Hall. Rudestam, K.E. & Newton, R.R. 1992: Surviving your dissertation. London: Sage. 23 APPENDIX 4: ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS 4.1 GUIDELINES FOR PROJECTS INVOLVING OTHER PEOPLE o The dissertation student should carry identification including information that allows a potential participant to contact the Department if she/he wishes, in order to ensure that the work is bona fide. Students who require letters of introduction and identification can obtain these from the Department Secretary. o Remember common courtesy. If you have made an appointment to meet with someone, be prompt. Professional people may be extremely busy, so be well organized and do not take up any more of their time than you have to. o Always ask if you may take photographs. Museums or excavation directors may have specific policies on this. In any case, it is polite to ask. o When requesting information from someone, be specific in your request. Do not expect someone else to do your data collection for you. 4.2 ACCESS TO PRIVATE LAND AND PROPERTY o Dissertation students must not attempt to conduct investigations on private land/property without the permission of its owners. If the property/land is publicly owned, permission must be obtained from the relevant authority/management. If requested to do so, a dissertation student must leave the land/property immediately and without protest. * Currently, the departmental ethics officer is Dr Marisa Lazzari. 24 APPENDIX 5: SAFETY CONSIDERATIONS Students are strongly discouraged from choosing a dissertation topic that involves hazardous activities. If a proposed dissertation topic involves any hazardous activities, it may be refused on the grounds of safety. In some cases, it may be possible to mitigate the hazard by following particular safety guidelines or wearing protective clothing etc. Decisions will be made on an individual, case-by-case basis. Students should make it clear, at the proposal stage, if they are intending to carry out any hazardous activities. The department will assess the risk and decide whether you should be allowed to proceed. If you are allowed to proceed, the approval may be conditional upon you following certain safety regulations. The student will have to carry out a risk assessment, along with their supervisor and the departmental safety officer *. Consult the section of safety in the Undergraduate Handbook and the Departmental Safety Policy. Fieldwork: If you are proposing to carry our fieldwork, you need to be aware of possibly hazardous activities (the following is a non-comprehensive set of examples): o Working alone (i.e. without anyone to get help) o Working near water o Working near cliffs (either from above or below) o Working in remote or exposed places (particularly if there is risk of bad weather) o Working in caves or deep holes o Working on unstable ground (e.g. around old mine workings etc.) o Working on building sites, or near heavy plant Laboratory Work: If you are carrying out lab work, there are many possibly hazardous activities (the following is a non-comprehensive set of examples): o Working with corrosive, flammable or toxic chemicals o Working with heat sources o Working with dangerous tools o Working in a dusty atmosphere o Working where chips or splashes of material are a risk to eyes (e.g. flint knapping) o Working with loud noise * Currently, the departmental safety officer is Dr Gill Juleff. 25 APPENDIX 6 DEPARTMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGY DISSERTATION TITLE APPROVAL FORM Name: Registration number: Degree course: Module code: ARC Dissertation title: Supervisor (signed): Date: I have read and understood the guidelines for Archaeology dissertations Candidate (signed): Date: 26 APPENDIX 7 DEPARTMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGY DISSERTATION PROPOSAL FORM Name: E-mail: Programme: Type of dissertation (delete as appropriate): ARC 3000 30-credit Archaeology dissertation (for single or combined honours students) ARC 3001 30 credit combined History and Archaeology dissertation (Hist & Arch students) ARC 3004 30 credit combined Ancient History and Archaeology dissertation (Anc Hist & Arch) Proposed topic: Brief description of the proposed project: PTO Primary sources to be consulted: 27 Secondary sources: Practical issues to be considered: e.g. travel / access to material /inter-library loan Comment by staff member(s) consulted (those doing a joint dissertation must consult a member of staff in each subject area): SIGNATURE OF STAFF MEMBER(S): DATE: SIGNATURE OF STUDENT: DATE: ………………………………………………………………………………………………………… TO BE FILLED IN BY DISSERTATION CO-ORDINATOR Date of receipt of form: Name of appointed supervisor: 28 APPENDIX 8 Department of Archaeology DISSERTATION SUBMISSION FORM To be submitted with two copies of your dissertation Student Number: Dissertation title: I certify that this dissertation is all my own work. Any material quoted or paraphrased from reference books, critical works etc. has been identified as such and duly acknowledged. Name (CAPS): Signed: Date: 29