Rev - Wharton GIS Lab

advertisement

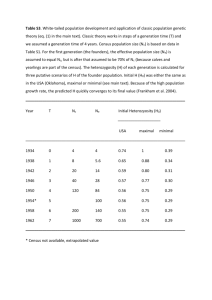

1 Rev. 8/19/02 wharton_082102.doc Talking points Wharton School, U Penn (Wachter meeting) Developing Community Information Systems With American Community Survey Summary Profiles and Administrative Records and GIS Applications Cynthia M. Taeuber U.S. Census Bureau and Jacob France Center, University of Baltimore It used to be that the decennial census was virtually “the only game in town” for demographic, social, and economic statistics for state and local government statistics. That is no longer true. State and local governments have administrative records they are using to develop statistics for small geographic areas. And the Census Bureau has been developing the American Community Survey to provide updated local statistics every year. The new data and the developing technology and software are letting local governments develop community statistical systems. As they do that, we are learning more about both the opportunities and the barriers. A big issue is that generally, the systems have been developed independently, idiosyncratic to each area. If you are looking for comparable social and economic information across areas, you are often out of luck. Across areas, you are more likely to find a Statistical Tower of Babel. The next generation needs coordination to develop system that is comparable across areas. 2 As everyone in this room would expect, estimates from the census long form and the American Community Survey differ from the results shown by administrative records. It isn’t that one is “right” and the other is “wrong.” Both have weaknesses and strengths, and the data are collected in different ways, for different purposes, and have different types of errors. The problem is to know what the differences are. We need to show the sampling error for survey statistics and we need to develop documentation to understand differences, so analysts can appropriately crossreference statistics from multiple data sets. There are differences from sampling and nonsampling errors, including data collection methods, sources of error, confidentiality protocols, and differences in universes, coverage, time periods, and the form of questions. Too often, we are unknowingly comparing the proverbial apples and oranges and titling the map a kumquat. Today, I want to give you a few examples of what to watch for when comparing summarized results from survey statistics and administrative records. And I want to suggest some next steps in the development of GIS products. 3 There are issues for community statistical systems in the use and display of sampling error that have yet to be addressed. Mapping software use only the survey estimates from the census long form and the American Community Survey. The map displays do not indicate the variability of the estimates or whether areas with different colors on the map are statistically different. Data users need to know whether apparent differences between the survey estimate and the administrative records are actual differences or sampling error. Otherwise, some is going to get into hot water by mistakenly making a big “to do” that a poverty rate has changed when it was just sampling error. Not showing the sampling error causes some obvious misinterpretation of the statistics. A Maryland State official asked me how it could be that Maryland’s counties had more people receiving public assistance than the 1990 census showed were poor. Were they welfare cheats? Once I calculated the standard errors for the poverty estimates for each county, we saw there was no problem with the poverty estimates – the counts from the administrative records fell within sampling error for the poverty estimates. We show the confidence intervals for the ACS. This was the first time many data users had ever had a real view of what sampling errors are like for block groups and census tracts. Even with the 1-in-6 sample of the census long form, 4 sampling errors are relatively large for small geographic areas such as census tracts and block groups. You wouldn’t know that from looking at most maps. Alerting data users to sampling errors from survey data could and should be done as a part of GIS software and mapping. Nonsampling errors can be a larger source of difference than sampling error. For analysts, it is an issue of knowing what garbage is going into the GIS map layers, what can be sanitized, and alerting data users as to what garbage remains displayed so beautifully on a map. What I mean by that, is how do we know that appears to be explicit relationships are actual relationships and not artifacts of hidden incomparabilities of the statistics? How DO you show the wobbly statistics on a map? Sometimes the statistics being layered in the maps aren’t really apples and oranges – sometimes it is more like Granny Smith apples and Delicious apples – close enough for certain purposes but not others – both can be snacked on but only one makes good applesauce. Surveys and administrative records both suffer from measurement, coverage, nonresponse, and processing errors that bias the results and affect the accuracy of the statistics. Data users need to know what the errors are and the extent of the errors so they can decide whether they can proceed with the comparisons. Nonsampling errors are extensively researched and documented for statistics from the decennial census and the American Community Survey. For 5 administrative records, documentation of errors and changes in state forms and procedures is rare and usually difficult for researchers to obtain. Administrative records that generate benefits for program participants are checked for errors. Electronic cross-checking of information has reduced inconsistencies among some types of administrative records, but not all. A vexing issue in administrative records is the geographic disparities in the assignment of residence between surveys and administrative records. Some administrative data sets are collected from establishments rather than households. Researchers can use some administrative records, such as drivers’ license records, to associate the person’s residence with their characteristics. But since drivers’ license records are not renewed every year, the address of record is wrong for some part of the population. Stuart Sweeney has shown that perceived time trends may actually be nothing more than improved protocols for collecting and recording address information. He is working on new estimation techniques to contend with that problem. Definitions, coverage, and data collection cycles, all can be different, further complicating comparisons. 6 In making comparisons among data sets, the universes need to be as similar as possible. Because of the lack of documentation of administrative records, and the many complicated requirements for program eligibility that differ among states, developing similar universes for analyses are a significant challenge. For example, are undocumented immigrants included in the administrative records as they are in the census and the ACS? The time references used in the questions, and the response choices, vary among data sources. Words, such as “race,” may be the same in data sets, but the definitions, and consequently the results, differ. Despite the problems, there is much that can be done to better use geographically-based data sets in conjunction with each other. (1) One step is to create a network of systems with comparable statistics. That implies documenting the administrative records, identifying sources of differences, and making such information readily available, such as through the Internet. (2) A second objective is to develop GIS software that displays the sampling error for survey statistics. The American Community Survey brings the potential to use GIS in spatial models that predict “what if” reactions to changes in policies and practices and events. (3) A third research objective is to further develop statistical models for estimates and projections that use administrative records with the 7 summarized geographic-area profiles from the American Community Survey. That implies coding administrative records to census geography. Individual privacy is maintained by using data sets matched to small geographic levels rather than individual people. Models that use multiple sources of geographically-based information provide the possibility of scenario-based planning for a community’s future to inform “what if” questions. We could better explore the likely impact of policy options, such as on community development. (4) Statistical policy should be coordinated among the multiple data sets to standardize, to the extent possible, definitions, data processing rules, and ways to ask demographic questions. My point is not to discourage researchers and GIS developers in using multiple data sets. Rather, it is to challenge us to understand the extent and type of errors in these data sets. The other challenge is to recognize the point when we should not push the statistics beyond their limits. Some data sets just can’t be compared. As the song says, you’ve got to know when to fold.