Does Local Competition Threaten Foreign Affiliates: Evidence from

advertisement

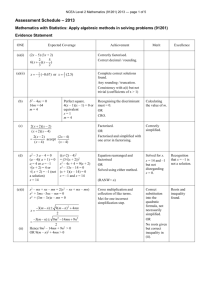

Paper submitted to 19th Chinese Economic Association (CEA) (UK) Annual Conference DOES LOCAL COMPETITION THREATEN FOREIGN AFFILIATES: EVIDENCE FROM CHINA Yi Wang Doctoral researcher Centre for International Business, University of Leeds (CIBUL), Leeds University Business School, The University of Leeds, Maurice Keyworth Building, Leeds LS2 9JT, UK Feb 2008 Abstract Using data for 153 Chinese manufacturing industries for 1995 and 2000-2003, this paper examines mutual productivity spillovers between foreign-owned (FOEs) and locally-owned (LOEs) enterprises. It is hypothesised that there is a curvilinear relationship with either negative or positive primary and secondary effects in each of the directions of mutual spillovers. Mutual spillovers are expected to be stronger where the technological gaps between FOEs and LOEs are smaller. The empirical model is applied to full sample (all industries) and sub-samples (science based, scale intensive, specialised suppliers, supplier dominated industries classified according to Pavitt's taxonomy). Results for 1995 are compared against those for 2000-2003 in order to examine the changes of mutual spillovers over time. This paper found evidence supporting the hypotheses. The main findings are (1) labour-productivity-measured mutual spillovers are significant and positive, (2) mutual spillovers principally follow a curvilinear relationship in each of their directions but the evidence is limited for specialised suppliers; the finding of positive primary effects confirm the widely observed simultaneous growth of FOEs and LOEs in China, (3) the scale and magnitude of mutual spillovers have been unbalanced in each of their directions, and (4) the hypothesis that mutual spillovers are subject to threshold effects of technological gaps is not fully supported in the estimations for the four types of industries, and the interactions may be conditional on the innovative features of industries. Keywords: Foreign direct investment, productivity spillovers, mutual spillovers Correspondence: e-mail address: bus3y6w@leeds.ac.uk 1 DOES LOCAL COMPETITION THREATEN FOREIGN AFFILIATES: EVIDENCE FROM CHINA Introduction Recent years have witnessed the magnification of the intensity and propensity of foreign direct investment (FDI) in China. Numerous studies have reached consensus that FDI has been a key engine driving the remarkable expansion of the Chinese economy. Indeed, as FDI represents “the transmission to the host country of a package of capital managerial skills, and technical skills” (Johnson 1972), the entry of multinational enterprises (MNEs) may bring significant benefits to local Chinese firms in terms of productivity. Among the issues on the impacts of FDI on host country local firms, one particular research topic that has been standing out in recent years is so-called “spillover effects”. That is, how far the presence of foreign affiliates stimulates the local-owned sector of industries, through ‘contagion effects’, ‘demonstration effects’, and competition between FOEs and LOEs. Empirical evidence shows that the positive spillovers have been most compelling, with a predominance of work finding in favour of the enhancement of local firms’ productivity (Caves 1974; Globerman 1979; Liu et al. 2000; and Zhu and Tan 2000). The literature agrees that there could be theoretically two way linkages between inward FDI and the performance of domestic firms. Inward FDI is expected to have a positive effect on the performance of domestic firms (Buckley, Clegg, and Wang 2002; Caves 1974; Globerman 1979; Li, Liu, and Parker 2001), and foreign MNEs are more likely to be attracted to industries where domestic productivity is higher and above 2 average profits realized. The recent FDI literature suggests the existence of reverse spillovers (e.g., Cantwell, 1995; Driffield and Love, 2003, Wei, Liu and Wang 2008). Driffield and Love (2003) observe that after initial transfer of firm-specific assets abroad, “firms operating in the foreign country then have to undertake the process of adapting this technology to a new environment, to take account of local working practices, available human capital and customers’ tastes for example” (p. 662) . Wei, Liu and Wang (2008) argue that mutual spillovers arise in a developing country through the successful combination of the firm-specific advantages of MNEs’ and the indigenous technology, and positive effects from LOEs can spill over to FOEs through the diffusion of local knowledge. Very few attempts have been made to empirically examine whether or not the presence of LOEs is linked to the improvement of the performance of foreign firms. Using the data for China, Buckley, Clegg, and Wang (2002) find that the direction of the relationships run from ‘presence of foreign affiliates’ to ‘ the productivity of LOEs’, not quite the reverse. This paper investigates whether the presence of local Chinese firms impacts on the productivity of their foreign counterparts, positively or negatively. This question severely warrants a close examination. The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the literature and proposes hypotheses. Section 3 presents data and methodology. Section 4 presents some of the empirical results and conclusions are summarized in section 5. Literature review Mutual spillovers arise when foreign investments bring technological and 3 productivity benefits to indigenous firms and the performance of indigenous firms also benefit the growth of foreign firms in the host country. The concept of mutual spillovers originates from the analysis of motives for FDI (Dunning 1993). Ownership advantages and advanced technological assets possessed by foreign firms enable MNEs to obtain a higher rate of return from their FDI operations (e.g., Hymer 1976). By attracting foreign investment, host countries may benefit from inward FDI through direct international technology transfer, productivity gains, and technological spillovers. Survey studies identified that such spillovers do not happen automatically, but many channels catalyse spillovers. Blomstrom and Kokko (1998) suggest that externalities from MNEs’ activities occur through demonstration effects, forward and backward linkages, competition, market access externalities, employee turnover, and imitation. The literature agrees that technology sourcing is an important motive for FDI despite of little empirical investigation has been done about this issue. Wei, Liu, and Wang (2008) note that the hypothesis of reverse spillovers implies that firms tend to invest in industries or places closer to technology leaders in order to benefit form technological spillovers. Driffield and Love (2005) found supporting evidence that technology generated by domestic firms in the manufacturing sector spilled over to MNEs in the UK, and this effect was significant only in research and development (R&D) intensive sectors. Studies on technology sourcing FDI stress that the concept of technological compatibility of MNEs is ambiguous and the significance of technological capabilities of domestic firms generates country and industry specific 4 advantages which attract inward FDI (e.g., Cantwell 1989; Neven and Siotis 1996). Mutinelli and Piscitello (1998) argue that, despite of possessing ownership-location-internalization (OLI) advantages (Dunning 1998), MNEs may still need to access local technology. This is because that firms’ inability to internalise all the needed knowledge and competencies forces them to acquire it outside. Empirical studies suggest that MNEs are more likely to explore superior local technologies in developed countries. Given the technological distance between foreign and local firms is not too long, channels of spillovers may be reversed. The establishment of joint ventures may create valuable learning opportunities for both foreign and domestic venture partners (Inkpen 2000). Mutual spillovers arise from the movement of knowledge-bearing workforce. Using a game theory approach, Gersbach and Schmutzler (2003) examine endogenised technological spillovers arising from employee turnover. They suggest that mutual spillovers occur when R&D personnel working for foreign firms changing to work for domestic firms and “take all their knowledge with them” (p. 180). Firms could obtain industry specific knowledge and establish a strong position in the market through the employment of a large number of experienced employees from competitors. With regard to developing countries, only a few studies have been carried out on mutual spillovers. Two conventional thoughts explain the reasons for the lack of this type of research. First, for MNEs that seek to access superior technologies, developing countries are not likely to be their desired location because competitive technologies are usually unavailable there. This view is opposed by Wei, Liu, and 5 Wang (2008), who argue that foreign investors may learn indigenous knowledge from domestic counterpart and, for foreign firms to be competitive in a developing country, the indigenous knowledge, such as the labour intensive technologies in manufacturing , local language, local customs, and local work ethic, is essential. Second, empirical studies present mixed results for spillovers from FOEs to LOEs in developing countries (e.g., Haddad and Harrison 1993; Hu and Jefferson 2002; Young and Lan 1997), which is usually reasoned that LOEs have inadequate absorbability to benefit from FOEs and therefore reverse spillovers may not occur since foreign investors can learn nothing from uncompetitive local firms. Opposing to this view, some literature argues that negative spillovers from competition effects may be only one part of the story and competitions in the long term will stimulate technological catch up of local firms (e.g., Cantwell 1995). Liu et al. (2000) stress that “the improvement in local technology in turn reduces the technological gap and forces foreign firms to import new technology to remain competitive and profitable in the host market” (pp.409-410). Empirical studies on China have been centred on productivity spillovers from FOEs to LOEs. Studies on mutual spillovers in China are very rare, and the only exception is the research conducted by Wei, Liu, and Wang (2008). While some empirical evidence supports the view that the productivity of Chinese LOEs is positively related to the presence of foreign investment in manufacturing industries (e.g., Buckley, Clegg, and Wang 2002), others found a mixture of both positive and negative spillovers (e.g., Hu and Jefferson 2002). For those mixed results, Buckley, 6 Clegg, and Wang (2007) argue that productivity spillovers from FOEs to LOEs actually follow a curvilinear relationship, which means that local labour productivity tend to be increasing (or decreasing) at an increasing (or decreasing) rate when the presence of foreign investment exceed (or below) a certain level. According to Buckley, Clegg, and Wang (2007), this curvilinear relationship implies the intricacy of spillovers, reflected by the many mixed results that traditional linear models can not explain. A significant failure of the traditional linear models is that it can not distinguish between the primary and secondary effects of spillovers. Primary effects measure the level of spillovers in relation with the level of foreign presence, which is what linear models intend to examine. The secondary effects measure the incremental effects of spillovers which relates to the changes of foreign presence. Assuming there are bidirectional externalities between LOEs and FOEs, it is expected that, after a certain period of interaction, some level of foreign productivity is linked with a certain level of local presence. In industries where local presence is low, foreign labour productivity may be higher than those with a high level of local presence. The available LOEs that survived through the competitions due to the early entry of FOEs may become very competitive. The improvement of local technological ability has pressed MNEs to transfer more advanced technologies to its affiliates in the host country. The reverse spillovers may be composed of primary and secondary effects. The primary effects of reverse spillovers are that an additional increase of local presence is (positively or negatively) related to the performance of FOEs. In a firm-level study, Wei, Liu, and Wang (2008) found that indigenous knowledge 7 spillovers have an impact on the productivity of OECD firms in China. Assuming the presence of LOEs in an industry proxies a pool of indigenous industry-specific knowledge, a greater primary reverse effect is expected to be positively related to a better resource of indigenous knowledge from which FOEs can draw during their operation in China. The secondary effects of reverse spillovers are that the performance of FOEs’ may increase (or decrease) beyond a certain level of local presence. First, an additional decrease of local presence may be related to an increase of FOEs’ performance. This is straightforward because efficient FOEs are able to force unproductive LOEs out of the market, and enjoy the growth of their market share as a result of reduced number of domestic competitors. Second, an additional decrease of local presence may be also related to a decrease of FOEs’ performance if the decrease of local presence is related to a general deficiency of an industry. Third, an additional increase of local presence, in the form of improved LOEs’ efficiency, may result in a decrease of FOEs’ performance if the LOEs are able to eventually overtake FOEs in the competition. In China, there are examples that LOEs that used to be downstream suppliers for MNEs are now able to exploit their comparative advantages of being a local and surpass FOEs after many years of development (e.g., the Lenovo’s acquisition of IBM’s PC manufacturing and services division in 2004, see Liu, 2007 for details). In summary, this study proposes a brief illustration of mutual spillovers through a set of curves as shown in figure 1. The scale of mutual spillovers (the dot curve) varies with the size of the technological gap between FOEs and LOEs. In a position where 8 technological gap is near zero, local labour productivity is too low to attract FDI and there are little spillovers from LOEs to FOEs, but spillovers from FOEs to LOEs can be maximally negative. In a position where the gap value is near one, LOEs are highly competitive and there are likely to be no overall benefit from LOEs to FOEs because there may be simultaneous positive and negative effects. In contrast, impacts from FOEs towards LOEs in this point are likely to be the maximum because of LOEs’ strong technology absorbability. In a position where the gap is greater than one, LOEs are significantly more productive than FOEs. Negative impacts from LOEs towards FOEs are most likely to dominant this stage. It is expected that the mutual spillovers are the greatest when the size of technological gap is moderate. In the case of figure 1, a moderate technological gap will be closer but not greater than one. Insert figure 1 here Following the framework discussed above, this study examines both directions of the mutual spillovers respectively, assuming that spillovers in each of the directions follow a curvilinear relationship. Three main research questions are put forward: (1) Are the presence of FOEs or LOEs positively and/or negatively related to the performance of their counterparts? (2) Do the magnitude of the mutual effects change beyond some level of the presence of FOEs or LOEs? (3) Are mutual spillovers stronger when there are smaller technological gaps between LOEs and FOEs? Data and methodology Data This paper uses two sets of pooled data for China’s 153 manufacturing industries from 2000 to 2003 and 121 out of 153 industries in 1995. Data are collected from 9 various issues of China’s Annual Industrial Statistical Report and the Third Industrial Census of the People’s Republic of China in 1995 published by the National Bureau of Statistics of China (NBS, 1997). The former is compiled by NBS but not publicly published. It follows the statistical standards as consistent as the Third Industrial Census. Both datasets cover all state-owned firms and those domestic and foreign firms whose annual turn over is above five million RMB. The industries refer to a three-digit classification according to Chinese convention. There are 196 sectors in total. To obtain balanced pooled data set, the total observations are 628 for 2000-2003 after deducting those industries without a complete data set of the four years examined or failing to pass other basic error checks, such as excluding those sectors that have not been largely liberalized and that do not enjoy free entry and exit (Wang and Yu , 2007). Figure 2 shows a matching trend of productivity growth for FOEs and LOEs during the two periods examined. Local labour productivity increased by around 1.6 times, while foreign labour productivity remained averagely 2.5 times higher than local labour productivity. The value of technological gaps between FOEs and LOEs has increased from 0.36 to 0.64, which indicates that LOEs have taken a faster pace than FOEs on the improvement of efficiency. These facts suggest the existence of technological catch-up of LOEs which is stimulated by the presence of foreign investment. The descriptive analysis initiates the empirical investigation to further inquire whether there are different levels of benefits on each of the directions of mutual spillovers and whether LOEs have benefited more from FOEs through mutual spillovers than do FOEs. 10 Insert figure 2 here Methodology Two expanded production functions are developed as follows: log( Y it( f ,d ) ) 0 1 log( MGTit( f ,d ) ) 2 log( SIZE it( f ,d ) ) 3GAPit 4 PRESENCE it( d , f ) 5 ( PRESENCEit( d , f ) ) 2 6 log( K it( d ) ) 7 log( L(`itd )` ) it ( f ,d ) log( Y it ) 0 1 log( MGTit ( f ,d ) 4 PRESENCE it (d , f ) ) 2 log( SIZE it ( f ,d ) 5 PRESENCE (d , f ) it (1.1, 1.2, 1.3, 1.4) ) 3GAPit GAPit 6 log( K it( f ,d ) ) 7 log( L(itf ,d ) ) it (1.5, 1.6) where subscripts i and t denote the industry and the year; superscripts d and f denote LOEs and FOEs, respectively. νit is the error term. For comparison purpose, the first model is initially estimated as a linear function, namely without the term ( PRESENCEit( d , f ) ) 2 . The linear regressions are denoted as model (1.1) for FOEs and model (1.2) for LOEs. Similarly, the curvilinear regressions are denoted as model (1.3) for FOEs and model (1.4) for LOEs. Models (1.5) and (1.6) examine the interactions between mutual spillovers and technological gaps. Y it is the output, measured by firms’ sales, SALESit , or value added, VADit . K it and L it are the capital and employment, respectively. All three quantities are conventional variables for a production function. According to Buckley, Clegg and Wang (2002), the control variables have been chosen to be the management input of firms, MGTit( f ,d ) , and the size of firms, SIZE it( f ,d ) . MGTit( f ,d ) is measured by sales fares, MGT1(it f ,d ) , or management fees, MGT 2(it f ,d ) . SIZE it( f ,d ) is measured by the value of fixed assets per firm, SIZE1(it f ,d ) , net fixed assets per firm, SIZE 2 (it f ,d ) , or total assets per firm, SIZE3(it f ,d ) . GAPit is the ratio of labour productivity of local firms to that of foreign firms. Following Liu et al. (2000), it is assumed that a high labour productivity reflects 11 advanced technology. Thus, a larger ratio means a smaller technological gap between LOEs and FOEs. A negative sign for the coefficient of GAP it is expected for the regression of FOEs’ performance, and, vice versa, a positive sign is expected to be linked with LOEs’ performance. PRESENCEit( f ,d ) is the presence of FOEs or LOEs. PRESENCE it(d ) is local presence measured by employment share of LOEs, LP1it , local capital share, LP2 it , local sales share, LP3it , local value added share, LP4 it , or LOEs’ labour productivity, LP5 it . Accordingly, PRESENCE it( f ) is foreign presence measured by employment share of FOEs, FP1it , foreign capital share, FP2 it , foreign sales share, FP3it , foreign domestic value added share, FP4 it , or foreign labour productivity, FP5it . The usage of different proxies for presence can help to justify the robustness of the estimation results. It is argued that labour productivity essentially reflects the technological ability of firms and it is a better proxy of the presence (Kokko 1996). ( PRESENCEit( d , f ) ) 2 is the squared form of (local or foreign) presence. The coefficient of PRESENCEit( d , f ) , 4 , measures the primary effects of the spillovers, and the coefficient of ( PRESENCEit( d , f ) ) 2 , 5 , measures the secondary effects of the spillovers. According to the discussion in previous section, the primary and secondary spillovers could be either positive, negative, or zero. PRESENCEit( d , f ) GAPit is the terms of interaction between the presence with technological gap. The coefficient of the interaction term, 5 , measures whether the influence of (local or foreign) presence on the performance of FOEs or LOEs become different if those effects are bounded with a technological gap multiplier. 12 Data are further divided into four sub-samples which are classified using Pavitt Taxonomy. According to Pavitt (1984), there are four types of industries with distinguished characteristics. They are the science based, scale intensive, supplier dominated, and specialised suppliers industries. For details of the industrial characteristics, see a summary by Malerba and Orsenigo (1996). Owing to the nature of the datasets used in this paper, it is not possible to distinguish the 153 (or 121) Chinese manufacturing industries by the input and output of R&D innovations within each industry, a methodology used by Pavitt (1984). However, this study employed several descriptive checks (using indicators show in table 1) to justify that a similar classification to Pavitt’s is appropriate for Chinese industries. More specifically, this study defines that science based industries at the two-digit level include chemicals, electrical and electronic engineering, petroleum, coking, and pharmaceuticals. The scale intensive industries include food and beverages, metals, rubber and plastics, transport equipment, and non-metallic mineral products. The supplier dominated industries include textiles, leather and footwear, lumber, wood and paper mill products, printing and publishing. The specialised suppliers include manufacturing of general and special purpose machinery, and instrument engineering. Table 1 shows that the science based industries have the largest value of scale indicators, and the specialised suppliers have the smallest value for most of the indicators. This is consistent with the characteristics predict ed by Pavitt taxonomy. It is worth noting that the supplier dominated industries have the largest total employment, number of firms and foreign presence (by capital and employment shares), and lowest 13 foreign labour productivity (during 2000-2003). This implies that this group of industries, particularly textiles, have been largely developed into labour intensive sectors where inward FDI are least productive among four types of industries because of its low technological content. It seems that LOEs have become most competitive in this group, as the technological gaps have been shortened dramatically since 1995 and became the smallest among all types during 2000-2003. Insert table 1 here Results All estimations are pooled ordinary least squares (POLS) with r andom effects models. The descriptive statistics and correlation matrices are shown in tables 2 and 3. Because all proxies of management input are highly correlated with most of other variables, only results without MGTit( f ,d ) are shown here. There is a potential serial correlation problem due to the introduction of interaction term into equations (1.5) and (1.6). However, the exclusion of variable GAP it may be unjustified if it causes the omission of important explanatory variable. (Note that most of the coefficients for GAP it are highly significant in the results). Therefore, for comparison purpose, all regressions have been re-estimated without GAP it , for which the results are highlighted by a * sign over the shoulder of the model numbers. Table 4 presents full sample results for 2000-2003. Tables 5 and 6 present results of sub-samples for 2000-2003. Table 7 presents full sample results for 1995. Because of limited number of observations in 1995, it is not possible to run regressions again for each sub-sample using the data of 1995. Due to space constrains, only the results using labour 14 productivity as proxy of PRESENCEit( f ,d ) are presented here. Results using capital share as a proxy of PRESENCEit( f ,d ) are similar to those of labour productivity. Regressions using employment share, sales share and value added share as proxies for PRESENCEit( f ,d ) did not produce reasonable results. The results that are not presented here are available from the author upon request. Insert table 2-7 here Full samples results In table 4, the full sample results for models (1.1) – (1.4) show significant positive mutual spillovers during 2000-2003. The results of linear estimations (models 1.1 and 1.3) are that mutual spillovers are positive and significant and the coefficients for FP5it are greater than those for LP5 it . This demonstrates that there is a general mutual beneficial relationship between FOEs and LOEs, and LOEs have produced greater benefits to FOEs than do FOEs. The results of curvilinear regressions are that all coefficients for primary and secondary effects are significant, although the secondary effects are very weak (mostly with a near-zero value for coefficient β5). While primary effects are all positive, secondary effects are unanimously negative, indicating that mutual spillovers on each of their directions are increasing at a decreasing rate. For spillovers from FOEs to LOEs, this means that the LOEs benefit from a low or moderate level of foreign productivity, but the scale of this benefit tends to fall when the efficiency of FOEs exceeds some level. This result is consistent with the findings by Buckley, Clegg, and Wang (2007), who argue that the industrial concentration of (overseas Chinese firms’) FDI in standardised goods market segments within industries means that the scope for technological spillovers is limited. Following their argument, this 15 paper suggests that the enhanced efficiency of foreign production as a whole within an industry indicates that spillovers from FOEs to LOEs are not sustainable. For spillovers from LOEs to FOEs, the results demonstrate that improved productivity of LOEs leads to an increase of reverse spillovers, but reverse spillovers may start to fall if LOEs’ efficiency is continually improved and goes beyond some level. The results for spillovers interacting with technological gaps (models 1.5 and 1.6 in table 4) are that the coefficient for FP5it becomes insignificant when the interaction term is introduced into the regression, while the coefficient for LP5it GAPit is only significant at 10% level. The results demonstrate that spillovers from FOEs to LOEs are significant and positive when the technological gaps are not too wide, while reverse spillovers are not strongly interacted with technological gaps, indicating that only one direction of the mutual spillovers are subject to the threshold effect of technological gaps during 2000-2003. In table 7, the results for 1995 are that mutual spillovers are significant and positive in linear regressions and the coefficient for FP5it are greater than those for LP5 it , which is consistent with the results for 2000-2003. This demonstrates that the scale and magnitude of mutual spillovers have been unbalanced in each of the directions for both periods examined. The greater benefits enjoyed by FOEs may be explained by MNEs’ comparative advantages, especially the ownership and internalization capability in the host country. Comparing the two periods examined, there were a larger portion of joint ventures (JVs) in 1995 than recent years. For most of foreign investors of JVs, they initially acquired local knowledge (Wei, Liu, and Wang 2008) and established vertical linkages with downstream and upstream suppliers through their Chinese partners who played an important role during the process where reverse 16 spillovers arose. Results of the curvilinear regressions for 1995 are that all primary effects are positive and significant and the secondary effects of spillovers from LOEs to FOEs have a particularly large negative coefficient. This demonstrates that, in industries where LOEs are very productive, there is a considerable declining trend of the benefits enjoyed by FOEs because FOEs are faced with competition pressure on the host factor and resource markets. During current years, more and more wholly owned foreign enterprises (WFOEs) are established, particularly by investors of previous JVs, or through the acquisition of the remainder of previous JVs’ ownership, such as the case of Electolux China (see Yang, 2004 for details). Compared with JVs, WFOEs have more experience of doing business in China and are better in coping with market and policy changes, and competition forces arising from improving local competence. The results for the regressions with interaction terms for 1995 contrast those for 2000-2003. It is found that interaction terms have only significant coefficients in models of reverse spillovers, but not for spillovers from FOEs to LOEs. This may be explained by the fact that FOEs have chosen to invest in industries where LOEs were most productive during the early period, while, during recent years, foreign investors have started to operate in industries where local production are not necessarily most efficient. This effect may have been enhanced with China becoming a member of WTO in 2001. After the WTO entry, foreign investors in China benefited from a series of reforms by the Chinese government, in particular the improvement of transparency and predictability of doing business in China. The reduced political and environmental risks have helped ensure the confidence of foreign 17 investors and stimulate FDI flows into all encouraged sectors. Also surprisingly, the results show that the coefficient for LP5it GAPit is positive and highly significant at the 1% level. This indicates that LOEs produced negative spillovers to FOEs when the technological gaps between them were small. Relating to the technological gap indicator for 1995 in table 1, this may be explained by the fact that the most competitive LOEs in 1995 were in science based industries. This reverse threshold effect of gaps in 1995 may be mainly sourced from this group of industries, of which, according to the results for 2000-2003 in table 5, the oligopolistic, high-tech and process innovation nature leads to the development of vigorous local rivalries for FOEs. The results for science based industries will be discussed further in the next section. Regressions for models without GAPit variable have produced unsatisfactory results, and have therefore been excluded in tables 5, 6 and 7. Sub-samples results In tables 5 and 6, the sub-samples results are that mutual spillovers are present and positive in all four types of industries, but there are different patterns of the curvilinear form of spillovers for each of the sub-samples. With regard to the linear models (1.1) and (1.2), all signs of spillovers are significant and positive except for science based industries, for which none of the coefficients of FP5it and LP5 it is significant at the 10% level. According to Pavitt (1984), science based industries are characterized by large oligopolistic firms, diversified competences, and process innovations. Firms of this type use innovations produced by firms within this group and also produce innovations that mainly serve users in the same group. The insignificance of linear form 18 mutual spillovers suggests that there are limited and possibly indirect connections between FOEs and LOEs within a science based industry, which may be due to a lack of incentives for intra-industry technological spillovers. With regard to the curvilinear models (1.3) and (1.4), the results are that mutual spillovers follow a curvilinear relationship in all sub-samples except for specialised suppliers. In table 6 (the eighth column from the left), the coefficient for LP5 2it is not significant at the 10% level. Specialised suppliers are characterized by technology-intensive activities by small and medium sized firms. Table 1 shows that technological gaps in this group are the widest among four types of industries, and the level of foreign presence and scale in this group are very low. The lack of secondary effects for reverse spillovers demonstrate that an increase of LOEs’ presence beyond some level can hardly produce either positive or negative influence on FOEs’ performance if the technological ability of LOEs is very low. The results also demonstrate that mutual spillovers occur despite of the highly idiosyncratic and tacit nature of knowledge specifically used in this type of industries (Malerba and Orsenigo 1996). The finding suggests that the possibility that FOEs and LOEs as specialised suppliers in the same industry are able to benefit from each other lie on some channels of inter-industry spillovers, such as improving their ability of adapting and tailoring products to the needs of users who are in a different type of industry. For models (1.5) and (1.6), the results show that the patterns of interactions are distinctive for each sub-sample. Results for science based industries are that mutual spillovers arise when there is a certain level of technological gaps, but, opposing the hypothesis, reverse spillovers become negative when there are smaller technological gaps (see the significantly positive 19 coefficient for LP5it GAPit ). The results demonstrate that mutual spillovers do not tend to be strong when both of LOEs and FOEs are very productivity in an industry because negative effects arise on one of the directions of mutual spillovers. Results for scale intensive industries show that the coefficient for FP5it GAPit are significant and positive while coefficients for the variables FP5it and GAPit become insignificant with the introduction of interaction term. This demonstrates that there is clearly a threshold effect for the ability LOEs are able to benefit from spillovers from FOEs in this type of industries. Another finding for scale intensive industries is that the coefficient for LP5it GAPit is not significant at the 10% level, implying the reverse spillovers are not subject to the threshold effect of gaps. This may be because that firms in these industries achieve competence mainly through scale economies. FOEs of this type naturally benefit from MNEs’ advantages of internalization, which enables them to integrate upstream or downstream suppliers efficiently. In China, LOEs of the type are largely state-owned enterprises (SOEs) for which the conventional proxy of presence may be biased because they do not have free entry and exit from the market. Results for supplier dominated industries are that the coefficient for FP5it GAPit (the sixth column from the left in table 6) is not significant at 10% level, implying the scale and magnitude of spillovers from FOEs to LOEs in these industries do not change with a certain level of technological gaps. Relating to the fact that LOEs in this group are most competitive relative to FOEs among four types of industries (see the largest value of technological gap indicator in table 1), this result is broadly consistent with the argument made by Wang and Blomstrom (1992) that spillovers are basically endogenous outcomes of the interactions 20 between local and foreign firms. More specifically, this result demonstrates that spillovers from FOEs to LOEs are not conditional on technological gaps when LOEs are highly competitive in a none-technology-intensive industry where industrial innovations are produced and applied in industries of the similar type. Results for specialised suppliers are that the coefficient for LP5it GAPit are not significant at the 10% level, indicating that reverse spillovers do not change if the relative technological ability of LOEs rises above a certain level. This result is consistent with the results for model (1.3) (the seventh column in table 6). It suggests that the deterministic factor that FOEs benefit from LOEs are not conditional on the size of technological gaps or the productivity of LOEs within the same industry, but the interaction with the end users in different industries that both FOEs and LOEs are serving. Coefficients for variables Kit and Lit are positive and significant in all estimations. Coefficients for the control variable log( SIZE it( f ,d ) ) are significant in full sample estimations, and vary in estimations for sub-samples. The varied results for log( SIZE it( f ,d ) ) justify the application of Pavitt taxonomy for Chinese industries. For example, all coefficients of log( SIZE it( f ,d ) ) are significant for scale intensive industries, while they are insignificant for supplier dominated industries which is composed of mostly only small firms. In addition, the coefficients for log( SIZE it(d ) ) in models for LOEs in science based industries (the third to sixth column from the left in table 5) are all insignificant, implying the lack of economies of scale for science based Chinese firms. Conclusions The results support the existence of mutual spillovers between FOEs and LOEs 21 within Chinese manufacturing industries. It is found that spillovers from FOEs to LOEs during 2000-2003 arose when there were smaller technological gaps, while spillovers from LOEs to FOEs in 1995 became negative when the technological gaps were small. More specifically, four findings of this paper follow. First, this paper finds that, among many proxies of (local or foreign) presence, labour-productivity-measured mutual spillovers are significant and positive. This result supports the view that China’s developmental strategies which have been to promote the growth of indigenous firms by encouraging inward FDI into the manufacturing industries have initiated a mutual beneficial relationship between FOEs and LOEs within the same industry. This mutual beneficial relationship has been essentially the improvement of labour productivit ies of both FOEs and LOEs. Second, it is found that mutual spillovers principally follow a curvilinear relationship in each of their directions, but this evidence is limited for the specialised suppliers. The unanimous results of positive and significant primary effects are broadly consistent with the findings of many previous studies which observed simultaneous growth of FOEs and LOEs in China (e.g., Buckley, Jeremy, and Wang 2002; Li, Liu, and Parker 2001). The unexpected results for specialised suppliers argue that the curvilinear relationship of spillovers from LOEs to FOEs may be conditional on a moderate level of technological ability of LOEs, and on the nature of an industry in terms of whether its innovations largely involve knowledge spillovers arising from interactions with upstream customers who are in a industry different from the one that innovation inventors belong to. 22 Third, the scale and magnitude of mutual spillovers have been unbalanced in each of their directions. It is found that FOEs generally benefit more from LOEs than do LOEs. The inequality of mutual spillovers suggests that China’s policy of encouraging inward FDI in order to benefit from technological spillovers from foreign investment have produced more benefits to FOEs than to LOEs. This, on one hand, seems to provide supporting evidence for the long lasting attraction of China as one of the most important host countries for MNEs. On the other hand, it indicates that there are still a lot more to do for Chinese government in terms of leveraging FDI to promote economic growth, such as creating more incentives for LOEs to learn, accumulate, and substantialise the benefit from FOEs through this mutual spillovers relationship. Last but not least, the evidence that mutual spillovers are subject to the threshold effects of technological gaps are limited for four types of industries classified using Pavitt taxonomy. This finding suggests that the hypothesis that mutual spillovers tend to be stronger when the technological gaps are smaller may be conditional on the innovative features of industries. The policy implication is that host country government need to carry out different approaches in the monitoring or promotion of mutual spillovers and need to pay attention to the industry-specific innovative factors when scheming these approaches. 23 Figure 1 An illustration of mutual spillovers Note: This is not a simulation from the empirical models, but this figure serves as an abstractive illustration. The breakdown point is assumed to be 1. The strength of spillovers from FOEs to LOEs is assumed to follow y=cos(x) and spillovers from LOEs to follow y=-sin(x), where y denotes spillovers, x denotes gap, and E(x)=3.2. Figure 2 Labour productivity and technological gap index (1995-2003) Firm performance GAP 12 0.95 10 0.85 8 0.75 6 0.65 4 0.55 2 0.45 0.35 0 1995 2000 2001 2002 1995 2003 Labour productivity of LOEs Labour productivity of FOEs 2000 2001 2002 2003 Ratio of LOEs labour productivity LOEs to FOEs 24 Table 1 Descriptive indicators for four types of industries classified according to Pavitt taxonomy Mean No. of industries Number of firms Averaged total assets of a firm Averaged total assets of a FOE Averaged total assets of a LOE Averaged sales of a firm Averaged value added of a firm Total capital Averaged capital of a firm Total employment Science based 29 (27) 1101.25 (2337.11) 1.33 (0.33) 1.45 (0.34) 1.22 (0.32) 1.26 (0.25) 0.30 (0.07) 296.72 (139.88) 0.33 (0.08) Scale intensive 78 (55) 878.68 (3250.13) 0.87 (0.25) 1.07 (0.55) 0.80 (0.23) 0.59 (0.17) 0.17 (0.04) 160.60 (124.18) 0.22 (0.06) Supplier dominated 28 (22) 1359.53 (4585.27) 0.86 (0.31) 0.75 (0.27) 0.81 (0.30) 0.68 (0.24) 0.34 (0.12) 155.09 (139.55) 0.18 (0.06) Specialised suppliers 18 (17) 1039.19 (2806.77) 0.55 (0.15) 0.80 (0.24) 0.48 (0.15) 0.46 (0.09) 0.12 (0.03) 143.52 (99.22) 0.15 (0.04) 33.66 (44.61) 24.36 (47.32) 40.52 (77.88) 28.65 (52.60) 0.04 0.04 0.03 0.03 (0.02) (0.02) (0.02) (0.02) 9.07 5.68 5.41 5.19 Averaged capital labour ratio (3.36) (2.50) (2.03) (1.92) 0.36 0.34 0.44 0.34 Foreign presence by capital share (0.23) (0.21) (0.22) (0.13) Foreign presence by employment 0.24 0.19 0.30 0.19 share (0.13) (0.14) (0.21) (0.08) 14.88 8.55 6.95 8.24 Labour productivity of FOEs (5.82) (3.88) (4.27) (4.48) 6.88 4.32 5.69 3.40 Labour productivity of LOEs (2.19) (1.39) (1.84) (1.12) 0.71 0.77 0.83 0.47 Technological gap (0.48) (0.45) (0.44) (0.29) Notes: Figures within parentheses are calculated using data of 121 industries in 1995. Averaged employment of a firm 25 Table 2 Descriptive statistics of all variables and correlation matrix (for models of FOEs 1.1, 1.3, and 1.5) (f) 1 log( MGT1it ) (f) 2 log( MGT 2 it ) (f) 3 log( SIZE1 it ) (f) 4 log( SIZE 2 it ) (f) 5 log( SIZE3it ) 6 GAPit 7 LP1it 8 LP2it 9 LP3it 10 LP4it 11 LP5it 2 12 LP1it 2 13 LP 2it 2 14 LP3 it 2 15 LP4 it 2 16 LP5 it (f) 17 log( K it ) (f) 18 log( Lit ) (f) 19 log( SALES it (f) 20 log( VADit ) ) Mean* 8.69 (NA) 9.19 (NA) 0.44 (0.10) 0.41 (0.14) 1.05 (0.41) 0.73 (0.43) 0.78 (0.89) 0.64 (0.79) 0.70 (0.76) 0.71 (0.77) 4.95 (1.62) 0.65 (0.80) 0.45 (0.65) 0.53 (0.62) 0.54 (0.62) 54.3 (6.31) 63.33 (21.46) 6.10 (4.74) 187.31 (73.34) 48.27 (17.93) Std. Dev.* 17.44 (NA) 17.64 (NA) 0.67 (0.21) 0.61 (0.27) 1.30 (0.74) 0.70 (0.32) 0.18 (0.10) 0.22 (0.14) 0.20 (0.18) 0.20 (0.17) 5.46 (1.93) 0.26 (0.16) 0.28 (0.20) 0.27 (0.24) 0.26 (0.23) 371.45 (37.28) 94.19 (23.31) 12.17 (8.92) 421.05 (102.87) 98.38 (25.82) 2 3 0.95 0.22 (NA) (NA) 0.24 (NA) 4 NA (NA) NA (NA) NA (NA) 5 0.32 (NA) 0.33 (NA) 0.90 (0.91) NA (0.93) 6 -0.45 (NA) -0.48 (NA) 0.00 (-0.07) NA (-0.19) -0.12 (-0.19) 7 -0.38 (NA) -0.40 (NA) 0.18 (0.08) NA (0.14) 0.09 (0.11) -0.03 (0.04) 8 -0.53 (NA) -0.54 (NA) 0.05 (-0.09) NA (0.02) -0.02 (0.03) 0.14 (0.13) 0.86 (0.84) 9 -0.49 (NA) -0.50 (NA) 0.07 (-0.01) NA (0.04) -0.05 (-0.02) 0.13 (0.19) 0.92 (0.92) 0.91 (0.85) 10 -0.50 (NA) -0.51 (NA) 0.06 (0.00) NA (0.05) -0.06 (-0.02) 0.16 (0.27) 0.91 (0.89) 0.91 (0.83) 0.98 (0.96) 11 0.10 (NA) 0.10 (NA) 0.28 (0.29) NA (0.30) 0.35 (0.33) 0.07 (0.27) 0.03 (0.12) 0.09 (0.18) 0.05 (0.14) 0.06 (0.16) 12 -0.42 (NA) -0.43 (NA) 0.18 (0.08) NA (0.14) 0.09 (0.11) -0.01 (0.05) 0.99 (1.00) 0.89 (0.86) 0.93 (0.93) 0.92 (0.90) 0.05 (0.14) 13 -0.59 (NA) -0.60 (NA) 0.04 (-0.10) NA (0.00) -0.02 (0.01) 0.18 (0.15) 0.82 (0.82) 0.98 (0.99) 0.88 (0.85) 0.89 (0.83) 0.10 (0.20) 0.86 (0.84) 14 -0.53 (NA) -0.55 (NA) 0.09 (-0.00) NA (0.04) -0.02 (-0.02) 0.17 (0.22) 0.89 (0.90) 0.93 (0.87) 0.98 (0.99) 0.97 (0.96) 0.08 (0.18) 0.92 (0.92) 0.93 (0.87) 15 -0.54 (NA) -0.56 (NA) 0.07 (0.01) NA (0.05) -0.04 (-0.02) 0.19 (0.31) 0.88 (0.87) 0.93 (0.84) 0.97 (0.95) 0.98 (0.99) 0.08 (0.20) 0.91 (0.89) 0.93 (0.85) 0.98 (0.97) 16 -0.02 (NA) -0.01 (NA) 0.15 (0.20) NA (0.23) 0.18 (0.23) 0.05 (0.14) 0.07 (0.11) 0.11 (0.15) 0.09 (0.13) 0.09 (0.14) 0.91 (0.95) 0.08 (0.12) 0.13 (0.17) 0.12 (0.16) 0.11 (0.17) 17 0.93 (NA) 0.98 (NA) 0.26 (0.46) NA (0.41) 0.33 (0.41) -0.52 (-0.26) -0.35 (-0.34) -0.52 (-0.45) -0.44 (-0.44) -0.45 (-0.44) 0.09 (-0.07) -0.39 (-0.35) -0.58 (-0.48) -0.49 (-0.46) -0.50 (-0.45) -0.01 (-0.13) 18 19 20 0.91 (NA) 0.95 (NA) 0.11 (0.23) NA (0.22) 0.17 (0.24) -0.39 (-0.26) -0.52 (-0.49) -0.61 (-0.48) -0.55 (-0.53) -0.56 (-0.54) -0.02 (-0.25) -0.56 (-0.50) -0.66 (-0.51) -0.60 (-0.56) -0.60 (-0.56) -0.09 (-0.26) 0.94 (0.91) 0.99 (0.98) Notes: * is the statistics of variables in original form without natural logarithm. NA denotes ‘not applicable’. The variable SIZE2(f)it has negative values, of which the natural logarithm become invalid. This variable has therefore been excluded in the correlation matrix. Figures without parentheses are from data of 153 industries from 2000 to 2003. Figures within parentheses are from data of 121 industries in 1995. Data of MGT1(f)it and MGT1(f)it are not available for 1995. 26 Table 3 Descriptive statistics of all variables and correlation matrix (for models of LOEs 1.2, 1.4, 1.6) (d ) 1 log( MGT1it ) (d ) 2 log( MGT 2 it ) (d ) 3 log( SIZE1it ) (d ) 4 log( SIZE 2 it ) (d ) 5 log( SIZE 3 it ) 6 GAPit 7 FP1it 8 FP2it 9 FP3it 10 FP4it 11 FP5it 2 12 FP1it 2 13 FP2 it 2 14 FP3 it 2 15 FP4 it 2 16 FP5 it (d ) 17 log( K it ) (d ) 18 log( Lit ) (d ) 19 log( SALES it ) (d ) 20 log( VADit ) Mean* 14.99 (NA) 25.50 (NA) 0.33 (0.06) 0.33 (0.09) 0.85 (0.25) 0.73 (0.43) 0.22 (0.11) 0.36 (0.21) 0.29 (0.24) 0.30 (0.23) 9.42 (4.47) 0.08 (0.02) 0.18 (0.06) 0.12 (0.09) 0.13 (0.08) 220.96 (39.46) 120.05 (105.52) 23.49 (48.27) 406.56 (280.31) 116.46 (75.36) Std. Dev.* 26.32 (NA) 38.61 (NA) 0.85 (0.10) 1.23 (0.19) 1.88 (0.56) 0.70 (0.32) 0.18 (0.10) 0.22 (0.14) 0.20 (0.18) 0.20 (0.17) 11.51 (4.43) 0.12 (0.04) 0.17 (0.07) 0.15 (0.12) 0.15 (0.11) 1444.29 (170.05) 187.57 (131.04) 31.35 (57.05) 655.04 (362.72) 185.32 (104.99) 2 3 0.93 0.45 (NA) (NA) 0.59 (NA) 4 0.44 (NA) 0.58 (NA) 0.97 (0.95) 5 0.43 (NA) 0.56 (NA) 0.92 (0.97) 0.91 (0.98) 6 -0.25 (NA) -0.26 (NA) -0.13 (0.14) -0.12 (0.13) -0.09 (0.11) 7 -0.15 (NA) -0.26 (NA) -0.35 (-0.13) -0.35 (-0.31) -0.24 (-0.24) -0.03 (-0.04) 8 -0.07 (NA) -0.19 (NA) -0.42 (-0.25) -0.42 (-0.35) -0.34 (-0.30) -0.14 (-0.13) 0.86 (0.84) 9 -0.09 (NA) -0.19 (NA) -0.33 (-0.10) -0.33 (-0.27) -0.22 (-0.20) -0.16 (-0.19) 0.91 (0.92) 0.91 (0.85) 10 -0.11 (NA) -0.21 (NA) -0.33 (-0.11) -0.34 (-0.27) -0.22 (-0.20) -0.13 (-0.27) 0.92 (0.89) 0.91 (0.83) 0.98 (0.96) 11 0.24 (NA) 0.27 (NA) 0.33 (0.46) 0.32 (0.42) 0.33 (0.48) -0.24 (-0.22) -0.17 (-0.09) -0.07 (-0.09) 0.00 (0.03) -0.03 (0.07) 12 -0.15 (NA) -0.23 (NA) -0.26 (-0.05) -0.26 (-0.23) -0.15 (-0.17) 0.08 (0.02) 0.95 (0.94) 0.74 (0.70) 0.83 (0.81) 0.83 (0.77) -0.13 (-0.06) 13 -0.14 (NA) -0.24 (NA) -0.36 (-0.19) -0.36 (-0.28) -0.28 (-0.24) -0.05 (-0.05) 0.88 (0.84) 0.95 (0.95) 0.89 (0.81) 0.88 (0.79) -0.06 (-0.06) 0.81 (0.78) 14 -0.12 (NA) -0.20 (NA) -0.23 (-0.00) -0.23 (-0.17) -0.11 (-0.11) -0.08 (-0.11) 0.89 (0.90) 0.81 (0.77) 0.94 (0.96) 0.93 (0.91) 0.02 (0.08) 0.89 (0.87) 0.86 (0.80) 15 -0.13 (NA) -0.20 (NA) -0.22 (0.00) -0.23 (-0.17) -0.10 (-0.09) -0.06 (-0.18) 0.89 (0.87) 0.79 (0.75) 0.92 (0.92) 0.94 (0.95) 0.00 (0.15) 0.89 (0.82) 0.84 (0.77) 0.98 (0.95) 16 0.09 (NA) 0.09 (NA) 0.13 (0.36) 0.12 (0.33) 0.12 (0.37) -0.08 (-0.06) -0.10 (-0.07) -0.02 (-0.10) 0.01 (-0.05) -0.01 (-0.04) 0.85 (0.91) -0.06 (-0.03) -0.01 (-0.05) 0.02 (0.01) 0.01 (0.04) 17 0.92 (NA) 0.98 (NA) 0.61 (0.47) 0.61 (0.46) 0.55 (0.42) -0.29 (-0.02) -0.27 (-0.30) -0.22 (-0.35) -0.21 (-0.24) -0.23 (-0.23) 0.24 (0.23) -0.25 (-0.22) -0.27 (-0.34) -0.22 (-0.18) -0.22 (-0.16) 0.08 (0.13) 18 19 20 0.90 (NA) 0.94 (NA) 0.43 (0.26) 0.43 (0.30) 0.37 (0.25) -0.28 (-0.10) -0.25 (-0.35) -0.15 (-0.34) -0.21 (-0.30) -0.22 (-0.28) 0.14 (0.08) -0.23 (-0.27) -0.21 (-0.34) -0.23 (-0.27) -0.24 (-0.25) 0.05 (0.02) 0.95 (0.93) 0.99 (0.98) Notes: * is the statistics of variables in original form without natural logarithm. NA denotes ‘not applicable’. Figures without parentheses are from data of 153 industries from 2000 to 2003. Figures within parentheses are from data of 121 industries in 1995. Data of MGT1(d)it and MGT1(d)it are not available for 1995. 27 Table 4 Regression results (foreign presence proxied by labour productivity) Full Sample (N=612) Log(SALES(f)it) Log(SALES(d)it) 1.1 1.1* 1.3 1.3* 1.5 1.5* 1.2 1.2* 1.4 1.4* 1.582 1.219 1.561 1.077 1.483 1.336 1.460 1.605 1.393 1.586 Constant (15.57)*** (15.11)*** (17.07)*** (13.22)*** (12.59)*** (16.80) *** (15.32)*** (16.58)*** (15.13)*** (16.66)*** -0.027 -0.065 -0.045 -0.094 -0.040 -0.057 -0.033 -0.034 -0.040 -0.039 log( SIZE 3 ( f , d ) ) (-0.83) (-1.92)* (-1.57) (-2.87)*** (-1.18) (-1.77)* (-1.32) (-1.30) (-1.69)* (-1.55) -0.151 -0.232 -0.083 0.139 0.174 GAP (-5.36)*** (-8.46)*** (-1.67)* (7.79)*** (9.86)*** 0.028 0.022 0.085 0.059 0.040 0.049 LP5 it (6.44)*** (5.02)*** (10.69)*** (7.17)*** (4.77)*** (7.49)*** -0.001 -0.001 LP5 2 (-8.15)*** (-5.20)*** -0.010 -0.018 LP5 it GAPit (-1.69)* (-5.37)*** 0.004 0.002 0.025 0.017 FP5 it (3.23)*** (1.98)** (8.63)*** (5.71)*** -0.000 -0.000 FP5 2 (-7.96)*** (-5.35)*** it it 1.6 1.6* 1.464 1.562 (17.00)*** (18.17)*** -0.065 -0.070 (-2.90)*** (-3.03)*** 0.098 (5.93)*** it 0.001 (1.15) -0.000 (-0.02) it 0.044 0.048 (12.17)*** (13.32)*** 0.645 0.754 0.582 0.749 0.656 0.685 0.670 0.672 0.573 0.604 0.517 0.504 log( K ( f , d ) ) (18.35)*** (25.28)*** (18.22)*** (26.26)*** (18.39)*** (21.75)*** (15.98)*** (15.34)*** (13.58)*** (13.43)*** (12.93)*** (12.32)*** 0.466 0.387 0.498 0.378 0.453 0.427 0.354 0.339 0.454 0.406 0.518 0.523 log( L( f , d ) ) (12.54)*** (11.08)*** (14.98)*** (11.40)*** (11.97)*** (12.35)*** (7.78)*** (7.17)*** (9.97)*** (8.44)*** (11.98)*** (11.84)*** Adjusted R2 0.946 0.940 0.957 0.946 0.946 0.946 0.857 0.852 0.870 0.859 0.887 0.885 F value 2137.642 2414.373 2290.121 2138.289 1800.068 2140.067 736.319 878.415 684.670 747.769 797.499 944.807 Note: All estimations use data for 153 Chinese manufacturing industries from 2000 to 2003. *, **, and *** denote significance at 10%, 5%, and 1% levels respectively. Figures in parentheses are t statistics. The results remain qualitatively unchanged when (1) VAD ( f , d ) replaces SALES ( f , d ) as dependent variable, FP5 it GAPit it it it it 2) GAP is alternatively measured by the ratio of Total Factor Productivity (TFP), and (3) SIZE 3 ( f , d ) is replaced by SIZE 2 ( f , d ) or SIZE1( f ,d ) . it it 28 it it Table 5 Regression results for science based and scale intensive industries (foreign presence proxied by labour productivity) Science based industries (N=116) Scale intensive industries (N=312) (f) (d) Log(SALES it) Log(SALES it) Log(SALES(f)it) Log(SALES(d)it) 1.1 1.3 1.5 1.2 1.4 1.6 1.1 1.3 1.5 1.2 1.4 1.6 1.324 1.181 1.786 1.168 1.152 1.547 1.417 1.213 1.336 1.023 0.954 1.302 Constant (7.79)*** (6.91)*** (8.70)*** (3.96)*** (4.09)*** (7.31)*** (10.69)*** (8.08)*** (8.46)*** (6.69)*** (7.22)*** (13.04) *** 0.268 0.247 0.300 0.129 0.076 0.076 -0.079 -0.084 -0.087 -0.166 -0.133 -0.096 log( SIZE 3 ( f , d ) ) (3.30)*** (3.06)*** (3.95)*** (1.46) (0.90) (1.23) (-2.15)** (-2.28)** (-2.30)** (-3.66)*** (-3.42)*** (-3.47) *** -0.149 -0.198 -0.547 0.058 0.088 0.026 -0.248 -0.259 -0.192 0.194 0.258 0.029 GAP (-3.27)*** (-4.16)*** (-4.35)*** (2.28)*** (3.41)*** (1.32) (-6.08)*** (-6.33)*** (-2.66)*** (7.33)*** (10.47)*** (1.31) 0.015 0.079 -0.010 0.124 0.220 0.134 LP5 it (1.50) (3.58)*** (-0.84) (9.09)*** (6.16)*** (7.83)*** -0.002 -0.007 LP5 2 (-3.32)*** (-2.92)*** 0.043 -0.009 LP5 it GAPit (3.31)*** (-0.94) -0.000 0.025 -0.000 0.007 0.065 -0.002 FP5 it (-0.22) (3.64)*** (-0.13) (2.79)*** (9.30)*** (-0.93) -0.000 -0.001 2 FP5 (-3.74)*** (-8.75)*** 0.076 0.157 FP5 it GAPit (9.86)*** (15.91) *** 0.836 0.803 0.756 0.776 0.650 0.367 0.562 0.542 0.572 0.774 0.550 0.312 log( K ( f , d ) ) (15.61)*** (14.84)*** (14.06)*** (8.32)*** (6.75)*** (4.54)*** (12.13)*** (11.56)*** (12.05)*** (11.18)*** (8.36)*** (5.50) *** 0.231 0.236 0.294 0.350 0.454 0.721 0.509 0.523 0.498 0.294 0.508 0.732 log( L( f , d ) ) (4.15)*** (4.31)*** (5.45)*** (3.45)*** (4.47)*** (8.64)*** (10.13)*** (10.36)*** (9.70)*** (3.93)*** (7.27)*** (12.28) *** Adjusted R2 0.978 0.980 0.980 0.780 0.808 0.892 0.959 0.959 0.959 0.856 0.889 0.945 F value 1040.033 934.927 927.009 82.693 81.604 159.323 1439.919 1209.779 1200.605 370.588 416.490 899.022 Note: All estimations use data for 153 Chinese manufacturing industries from 2000 to 2003. *, **, and *** denote significance at 10%, 5%, and 1% levels respectively. Figures in parentheses are t statistics. The results remain qualitatively unchanged when (1) VAD ( f , d ) replaces SALES ( f , d ) as dependent variable, it it it it it it it it 2) GAP is alternatively measured by the ratio of Total Factor Productivity (TFP), and (3) SIZE 3 ( f , d ) is replaced by SIZE 2 ( f , d ) or SIZE1( f ,d ) . it it 29 it it Table 6 Regression results for supplier dominated and specialised suppliers industries (foreign presence proxied by labour productivity) Supplier dominated industries (N=112) Specialised suppliers (N=72) Log(SALES(f)it) Log(SALES(d)it) Log(SALES(f)it) Log(SALES(d)it) 1.1 1.3 1.5 1.2 1.4 1.6 1.1 1.3 1.5 1.2 1.4 1.6 2.279 2.485 2.280 1.726 1.578 1.748 2.512 2.474 2.542 0.308 -0.203 1.101 Constant (11.01)*** (14.40)*** (13.01)*** (9.29)*** (8.60)*** (9.24)*** (7.75)*** (7.36) *** (7.88) *** (2.01) ** (-1.16) (8.13) *** -0.049 -0.063 -0.056 -0.092 -0.072 -0.098 0.216 0.219 0.220 -0.031 -0.025 -0.013 ( f ,d ) log( SIZE 3 ) (-0.76) (-1.21) (-1.04) (-1.48) (-1.20) (-1.55) (2.76)*** (2.68) *** (2.83) *** (-1.68)* (-1.48) (-1.01) -0.506 -0.633 -0.450 0.176 0.268 0.144 -0.984 -0.985 -0.893 1.054 1.518 0.124 GAP (-7.52)*** (-10.41)*** (-7.67)*** (3.78)*** (5.10)*** (2.61)** (-8.81)*** (-8.46) *** (-3.42) *** (10.17) *** (12.20) *** (1.09) 0.017 0.057 0.067 0.196 0.221 0.211 LP5 it (5.30)*** (6.32)*** (4.96)*** (11.34)*** (2.21) ** (5.40) *** -0.000 -0.003 LP5 2 (-4.56)*** (-0.25) -0.032 -0.031 LP5 it GAPit (-3.78)*** (-0.42) 0.039 0.074 0.031 0.077 0.224 0.010 FP5 it (7.87)*** (6.14)*** (3.38)*** (11.28) *** (7.63) *** (1.30) -0.001 -0.006 FP5 2 (-3.11)*** (-5.03) *** 0.007 0.233 FP5 it GAPit (1.10) (10.12) *** 0.439 0.303 0.351 0.263 0.204 0.273 0.275 0.274 0.245 0.499 0.224 0.155 log( K ( f , d ) ) (6.37)*** (4.93)*** (5.58)*** (3.98)*** (3.12)*** (4.03)*** (2.51)*** (2.33) ** (2.11) ** (6.06) *** (2.66) *** (2.20) ** 0.596 0.722 0.689 0.737 0.798 0.727 0.691 0.691 0.725 0.584 0.845 0.888 log( L( f , d ) ) (8.63)*** (11.72)*** (10.84)*** (11.54)*** (12.45)*** (11.10)*** (6.64)*** (6.25) *** (6.26) *** (7.33) *** (10.49) *** (13.28) *** AdjustedR2 0.968 0.972 0.970 0.958 0.957 0.957 0.939 0.938 0.939 0.979 0.988 0.988 F value 667.078 654.351 600.002 504.912 414.602 411.153 219.415 179.569 181.675 657.245 942.256 987.383 Note: All estimations use data for 153 Chinese manufacturing industries from 2000 to 2003. *, **, and *** denote significance at 10%, 5%, and 1% levels respectively. Figures in parentheses are t statistics. The results remain qualitatively unchanged when (1) VAD ( f , d ) replaces SALES ( f , d ) as dependent variable, it it it it it it it it 2) GAP is alternatively measured by the ratio of Total Factor Productivity (TFP), and (3) SIZE 3 ( f , d ) is replaced by SIZE 2 ( f , d ) or SIZE1( f ,d ) . it it 30 it it Table 7 Regression results using data of 1995 (foreign presence proxied by labour productivity) Full Sample (N=121) Log(SALES(f)it) 1.3 2.108 (11.06)*** 0.103 (1.93)* -1.078 (-6.62)*** 0.638 (6.72)*** -0.026 (-6.35)*** 1.1 2.293 (8.40)*** 0.203 (2.76)*** -0.507 (-1.91)* 0.086 (1.71)* Constant log( SIZE 3 (it f , d ) ) GAPit LP5 it LP5 2it 1.5 2.728 (10.75)*** 0.208 (2.86)*** -1.169 (-6.71)*** 0.010 (0.23) 1.2 1.354 (5.63)*** 0.105 (2.76)*** 0.222 (1.18) Log(SALES(d)it) 1.4 1.162 (4.86)*** 0.090 (2.59)*** 0.376 (1.88)* 1.6 1.409 (5.48)*** 0.100 (2.62)*** 0.078 (0.29) 0.137 (5.69)*** LP5 it GAPit 0.032 (3.45)*** FP5 it FP5 2it 0.085 (3.33)*** -0.001 (-2.58)*** FP5 it GAPit 0.436 (5.00)*** 0.600 (7.64)*** 0.923 289.448 log( K it( f , d ) ) log( L(itf , d ) ) Adjusted R^2 F value 0.178 (2.42)** 0.836 (12.17)*** 0.951 391.7178 0.364 (4.40)*** 0.647 (8.50)*** 0.932 277.181 0.505 (4.79)*** 0.469 (4.83)*** 0.935 347.776 0.414 (4.04)*** 0.553 (5.67)*** 0.939 309.639 0.013 (0.55) 0.052 (0.89) 0.501 (4.62)*** 0.475 (4.77)*** 0.936 292.285 Note: *, **, and *** denote significance at 10%, 5%, and 1% levels respectively. Figures in parentheses are t statistics. The results remain qualitatively unchanged when (1) VAD ( f , d ) replaces SALES ( f , d ) as dependent variable, 2) GAP is alternatively measured by the ratio of Total Factor Productivity (TFP), it it it and (3) SIZE 3 ( f , d ) is replaced by SIZE 2 ( f , d ) or SIZE1( f , d ) . it it it 31 References Blomstrom, Magnus and Ari Kokko (1998), "Multinational Corporations and Spillovers", Journal of Economic Surveys, 12 (3), 247-277. Buckley, Peter J., Jeremy Clegg, and Chengqi Wang (2002), "The Impact of Inward FDI on the Performance of Chinese Manufacturing Firms", Journal of International Business Studies, 33 (4), 637-655. Buckley, Peter J., Jeremy Clegg, and Chengqi Wang (2007), "Is the Relationship between Inward FDI and Spillover Effects Linear? An Empirical Examination of the Case of China", Journal of International Business Studies, 38 (3), 447-459. Cantwell, John (1995), "The Globalisation of Technology: What Remains of the Product Cycle Model?", Cambridge Journal of Economics, 19(1), 155-174. Caves, Richard E. (1974), "Multinational Firms, Competition, and Productivity in Host-Country Markets", Economica, 41 (162), 176-193. Driffield, Nigel and James H. Love (2003), "Foreign Direct Investment, Technology Sourcing and Reverse Spillovers", The Manchester School, 71 (6), 659-672. Driffield, Nigel and James H. Love (2005), "Who Gains From Whom?: Spillovers, Competition and Technology Sourcing in the Foreign-Owned Sector of UK Manufacturing", Scottish Journal of Political Economy, 52 (5), 663-686. Dunning, John H. (1988), "The Eclectic Paradigm of International Production: A Restatement and Some Possible Extensions", Journal of International Business Studies, 19 (1), 1-31. Dunning, John H. (1993), Multinational Enterprises and the Global Economy, First edition, London: Addison-Wesley. Gersbach, Hans and Armin Schmutzler (2003), "Endogenous Technological Spillovers: Causes and Consequences", Journal of Economics and Management Strategy, 12 (2), 179-205. Globerman, Steven (1979), "Foreign Direct Investment and 'Spillover' Efficiency Benefits in Canadian Manufacturing Industries", Canadian Journal of Economics, 12 (1), 42-56. Haddad, Mona and Ann E. Harrison (1993), "Are There Positive Spillovers from Direct Foreign Investment?: Evidence from Panel Data for Morocco", Journal of Development Economics, 42 (1), 51-74. Hymer, Steven H. (1976), "The International Operations of National Firms: A Study of Direct Foreign Investment", Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press (Monographs in Economics). Inkpen, Andrew C. (2000), "Learning Through Joint Ventures: A Framework of Knowledge Acquisition", Journal of Management Studies, 37 (7), 1019-1044. Johnson, Harry G. (1972), "Survey of the issues," in Direct Foreign Investment in Asia and Pacific, Peter Drysdale (Ed.), Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1-17. Kokko, Ari (1996), "Productivity Spillovers from Competition between Local Firms and Foreign Affiliates", Journal of International Development, 8, 517-530. Li, Xiaoying, Xiaming Liu, and David Parker (2001), "Foreign direct investment and productivity spillovers in the Chinese manufacturing sector", Economic Systems, 25 (4), 305-321. Liu, Xiaming, Pamela Siler, Chengqi Wang, Yingqi Wei (2000), "Productivity Spillovers from Foreign Direct Investment: Evidence from UK Industry Level Panel Data", Journal of International Business Studies, 31 (3), 407-425. Malerba, Franco and Luigi Orsenigo (1996), "The Dynamics and Evolution of Industries", Industrial and Corporate Change, 5 (1), pp. 51-87. Mutinelli, Marco and Lucia Piscitello (1998), "The Entry Mode Choice of MNEs: An Evolutionary approach", Research Policy, 27 (5), 491-506. Neven, Damien and George Siotis (1996), "Technology Sourcing and FDI in the EC: An Empirical 32 Evaluation", International Journal of Industrial Organization, 14 (5), 543-560. National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), China. (1997), "The Data of the Third National Industrial Census of The People's Republic of China in 1995", Beijing: China Statistics Press. Pavitt, Keith (1984), "Sectoral Patterns of Technical Change: Towards a Taxonomy and a Theory", Research Policy, 13 (6), 343-373. Wang, JianYe and Magnus Blomstrom (1992), "Foreign Investment and Technology Transfer: A Simple Model", European Economic Review, 36 (1), 137-155. Wang, Chengqi and Li Yu (2007), "Do Spillover Benefits Grow with Rising Foreign Direct Investment? An Empirical Examination of The Case of China", Applied Economics, 39 (3), 397-405. Wei, Yingqi, Xiaming Liu, and Chengang Wang, (2008), "Mutual Productivity Spillovers between Foreign and Local Firms in China", Cambridge Journal of Economics, 1-23. Yang, Yan (2004), "Being a WFOE a Growing Trend", China Daily, page 11, 14 Aug 2004, Beijing. Young, Stephen, and Ping Lan (1997), "Technology Transfer to China through Foreign Direct Investment", Regional Studies, 31 (7), 669-679. Zhu, Gangti and Kong Yam Tan (2000), "Foreign Direct Investment and Labor Productivity: New Evidence from China as the Host", Thunderbird International Business Review, 42 (5), 507-528. 33

![[DOCX 51.43KB]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/007172908_1-9fbe7e9e1240b01879b0c095d6b49d99-300x300.png)