Genghis Khan: (1162-1227) Sources: Most of the information we

advertisement

Genghis Khan: (1162-1227)

Sources:

Most of the information we have about Genghis Khan and the Mongols comes from two Mongolian

sources. Firstly, The Secret History of the Mogols, which survived in Chinese phonetic script and

was written immediately after the death of Genghis Khan. It was commissioned probably by one of

the sons of Genghis at a gathering of scribes and sources at Auraga (the original Mongol capital) in

1228, the 'year of the rat'. This is contested by scholars who cannot agree which 'year of the rat' it

may have been written in! The Secret History has been described as both an Epic, in the Greek

tradition, and a great historical work. However it is worth bearing in mind that the Mongols had

neither a literary tradition nor any known historians. It was not however a hagiographic work,

instead it sort to portray Genghis as a great man, revealing that he way afraid of dogs, killed his

half-brither aged ten in cold blood, and was chastised on many occasions by his mother.

Secondly, in excerpts in Uighur script in the Altan tobchi (Golden Summary) and Altan debter

(Golden book). Both of which have been used, translated and reinterpreted throughout history

particularly by the 13th century Persian chronicler Rashid ad-Din, from whom much of our

knowledge comes as the Uighur scripts no longer exist.

Note on spelling: All the sources I have looked at lack any standardisation of names of people or

places, I have tried to be consistent throughout

Context to his birth:

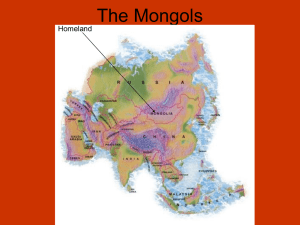

Around AD 800 people first settled in the valleys made by the Onon and Khorkh rivers, living in

obscurity for 400 years. The Mongols (or Tartars as they described themselves in this period) by

the late 11th century were a nomadic pastoral people living in small family units and traversing the

plains around lake Baikal. This area was known as the 'Steppe', a Russian word meaning 'sea of

grass'. In the west they were viewed as little more than beggars, leading primitive lives and lacking

the urbanisation and cultural tradition of their Chinese counterparts. In the summer temperatures

could top 40°C, in the winter freezing winds blew across from Siberia.

.

At the end of the 11th century the Mongols believed their anarchy would end through the rule of a

great Emperor. This man would receive the title of 'khan' and rule over his people to make the

Mongols great. They believed that their could only be one true Emperor on earth as their was one

God in heaven.

At this time Temudjin, one day to be Genghis Khan was born, in the spring of1162, the Year of the

Horse by the Asian calender. The meanings of his name are hotly debated. It is believed to be a

Tartar name, however others claim that it could derive from 'tomor' meaning 'iron'. His early years

are shrouded in myth and mystery as the man became a significant figure in Mongol folk history.

His father, Yesugei, was the head of the Kiyat, a subclan of the Borjigin clan. He came from a

lineage of Khan's who had ruled in the area but during Yesugei's time internal rivalries had

diminished the political organisation of the clan. Although of limited political power, he allied

himself with Togrul, 'falcon' (also known by Chinese name of Ong Khan), head of the Kerait, a

much more significant clan, and they became 'sworn brothers'. This was a common practice

amongst the Mongols by which clan heads extended their political influence and diplomatic

relations.

Temudjin's mother, Yulun came from the Markit tribe. His respectable background is often

forgotten in light of the myths which surround him. In folklore two diverging stories of the

founding of the Mongol Empire existed. The first stated that Temudjin was the son of a blue wolf

and a red doe, the second that he had been conceived by a divine light which had entered in through

-1-

the roof of his mother's house and impregnated her.

Temudjin grew up on the banks of the river Onon, where Yesugei had his camp.

Around the age of eight Temudjin's father was assassinated by the Tartar's. Myth has it that he was

poisoned by his rivals after drinking with them at their camp and died upon his return home. After

this, the remainder of his family were cast out from the clan, surviving on wild plants and traversing

the wilderness.

Temudjin developed a strong personality, resourceful and determined. At sixteen, he married his

first wife Borte, a member of his mother's clan the Ongirads. Borte has been betrothed to the boy

since the age of eight, his father deeming her a suitable match. As a dowry, a black sable gown was

given to Temujin which he later offered to Toghrul in exchange for his protection and influence

uniting the Mongol clans under Temujin.

Shortly after this Borte, herself a forceful woman recorded in many paintings from this period, was

abducted by the Markit and given as wife to Chilgerboko, a member of the clan's aristocracy. The

abduction was intended as a revenge as Temujin's father had stolen Hoelun, Temujin's mother from

the Markits years previously. Despite having increased his status through his new in-laws he still

lacked troops or armed support of his own. Temujun approached his uncle-the man to whom his

father had sworn allegiance, for help in recovering Borte. Together with Temujin's childhood

friend, Jamuka and an ally he had gained in his years in the wilderness, Boorchu, a three army

attack defeated the Merkets and recovered Borte, who soon gave birth to a child, Jochi ('visito' or

'guest') believed to be an illegitimate son from her time in captivity.

After this, the clan lived with Jamuka's clan for a while, moving from a hunters existence in the

mountains to a herder society on the steppe, until their friendship turned into rivalry and they split

in 1181.Temujin now seemed determined to become a warrior leader of his own and spent the next

decade assimilating neighbouring clans with his own, offering then fierce loyalty in return for their

support. Similarly, Temujin's clan acted as a vassal of Togruhl's, successfully completing military

campaigns in his name, such as against the Jurkin. Political survival on the steppe was a process of

careful military strategy-playing the various weaker clans off against each other and ensuring none

developed an overwhelming influence. Temujin recognised that whilst this system existed these

clans were destined to remain vassals of external political rulers. He knew that to overthrow this

system he needed to kill military leaders after they were defeated, and absorb the civilians into his

own clan, thus reducing the opposition and strengthening his own following. Interestingly, Temujin

adopted a son from each clan he defeated, symbolising his intent to unite the tribes of the region

into a greater political entity.

Temujin had proven himself a strong leader and had successfully

protected his new clan. Rivalry with Jamuka had intensified, but the

latter had discredited himself amongst the Mongols after reportedly

boiling seventy captives alive, thus destroying their soles and

annihilating them. Conversely, Temujin had developed a small, but

loyal following and was looked on much more favourably by the

small scattered clans.

Despite this however, Tonghul continued to play the rivals off each

other; refusing to acknowledge full support for Temujin by rejecting

an offer of marriage between Temujin's first child Jochi and Toghul's

daughter. Temujin's success on the steppe concerned the blood

brother of his uncle, and shortly after the failed marriage

negotiations, Togul plotted to annihilate the clan. Successfully

gathering a band of supporters from all over the region, Temujin

defeated the old Khan with an army which transcended race and

-2-

ethnicity. This was a major feat for the Temujin, who had freed the Mongol tribes from a relentless

cycle of political disputes.

In 1195 a meeting of the plenary assembly pronounced him 'khan'. This developed into Tchingis

Qaghan, a controversial title either understood to mean 'universal ruler' or a Turkic derivation of

'oceanic sovereign'.

Like other chieftains, he owned no land, and that which he did oversee was wild, with bleak winters

and dry summers.

Over time Genghis consolidated his power in several ways. Firstly, he created the yasak- a political

and moral code which incorporated his ancestral traditions into a new, centralised system. This

centralisation was founded in the Mongols belief in one great Emperor. To achieve this Genghis

had to defeat his great helper but also his rival for power, Tughrul now proclaiming himself Khan of

the Kereits. Using a mixture of military force and diplomatic cunning, he attempted to defeat the

ageing Toghrul which he did successfully, and by 1203 Tughrul was dead.

Physical features:

The sources describe him as tall, with a noble beard and eyes like a cat's.

Personality attributes:

The Mongols gained a reputation for being physically robust, able to withstand any climate or

hardship. Genghis Khan was certainly renowned for the strength of his personality.

He was also notoriously cruel when he needed to be to achieve diplomatic ends, such as crushing

the Kereits as an example of the wrath which would be felt by those who were treacherous. By his

nature he disliked the urban culture of China and the mercantile attitude of the Islamic lands in the

West.

He was illiterate, although came to appreciate the advantage of a royal seal and the value of writing.

Genghis Khan was quick to reward merit, and his strong leadership relied on a faithful collection of

followers and warriors to whom his loyalty was absolute.

Genghis had a large family, bringing home a new wife from every campaign. Rashid, the thirteenth

century Persian chronicler maintained that Genghis had a harem of five hundred wives and

concubines. A favourite wife accompanied him on each campaign. Despite his array of women

there is no evidence that the Khan had a passionate love affair. His first wife Borte, was recaptured

from the Merkits more on a point of honour and strategic disposition than due to a long standing

affection for her.

Military expansionism:

The heart of Genghis Khan's success was his military defeats of neighbouring tribes, and his ability

to incorporate their lands into his domain, later to become the Mongol Empire. At the time of

Genghis Khan's death his army amounted to 129, 000 men, not including the tens of thousands

more operating in China. This roughly amounted to 1 in 10 men being active in the army,

illustrating the highly militarised nature of the Mongolian imperial vision.

Military Organisation:

The army was organised into units or toumen of ten, in hundreds and thousands. The smallest squad

was an arban, a unit of 10 men. Genghis successfully substituted the idea of traditional clan

solidarity for that of these fighting units, instructing the soldiers to live and fight together as

brothers. 10 arban formed a zagun, which collectively elected a leader. 10 of these companies

-3-

formed a battalion, or mingan. Ten mingan then formed a tourmen, the leader of which was

selected by the Khan. This decimalised structure is believed to have come from earlier Turkic

tribes. Genghis applied it not only to the military but across the society he ommanded.

Horsemen were split into heavy and light cavalry, the former wearing complete body armour This

meant that each soldier bore the responsibility and consequently took punishment for all deeds in

his unit. The most common weapon was the crossbow, versatile for both short and long distance

combat. Horses were also crucial, each man having at least three at any one time. Indeed horses

were central to the lifestyle of the Mongols, used for transportation, milked for food and ridden into

combat.

Under the new Mongol Empire anyone from shepherds to camel boys could advance through the

ranks to the status of general. Every healthy male between fifteen and seventy took an active part in

military service.

Many military formations were used successfully by the Khan, including the 'Tumbleweed' or

'Moving bush formation' and the 'Lake Formation'. The first involved the dispersal of arbans from

various directions silently in the pre-dawn darkness. This disorientated the enemy, making it

difficult for them to calculate numbers of the opposition. The squads then dispersed quickly,

leaving the enemy wounded and unable to retaliate. The Lake formation by contrast, entailed a long

train of troops advancing, firing arrows then falling back and dispersing as the row behind replaced

them. This created a 'ripple' effect of arrows. These two techniques would be followed by a final

formation, the 'chisel', consisting of a narrow yet deep front of men which concentrated an attack on

one point. The enemy, spreading itself thin to meet the 'Lake formation' could now quickly be

eradicated as the 'Chisel' worked its way down the line. These techniques are believed to be a

combination of traditional fighting practices and hunting methods Temujin had learned in his youth.

Genghis Khan also had a personal guard-one of the most notorious and feared military units in

history. They were as close to him as brothers and rode everywhere with him, totalling 70 in

daylight and 80 by night in its early years and reaching one thousand by the height of the Khan's

military career, led by Jebei, his 'Arrow'.

Military campaigns were carefully planned. A series of scouts were sent to check out trails, supply

depots were carefully positioned and water sources controlled. Older methods of communication

were used, such as torches, whistling arrows, smoke, flares, flags and a complex system of arm

signals, as used in hunts.

Scouts or 'arrow riders' were particularly strategic, riding non-stop for days, eating and sleeping

along the way and changing horses when they were fatigued, in order to deliver information to

armies.

The Moguls avoided large scale battles, instead operating a system of harassment to exhaust the

enemy, including placing camp fires where they had no camps and dressing straw mannequins as

soldiers. They travelled without a supply train during desert crossings, instead taking an engineer

corps which could build whatever they needed on the spot from materials available.

Genghis has been best remembered for his military genius and his innovative approach to warfare.

For example, noticing that after a victory, strict military order was often abandoned as soldiers

jostled to raid a camp, the Khan banned looting until a complete victory had been secured. Then

organised looting took place, in which the Khan himself distributed the spoils of war. Similarly,

influenced by the circumstances in which a raid had left his mother when he was a child, Genghis

ordered that a soldiers share be distributed to each widow and orphan of a soldier. This inspired

confidence in the poorest members of the now assimilated tribe and in turn loyalty for their new

clan head.

-4-

Map (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Genghis_Khan)

Military Campaigns:

These began in 1202 when he vowed to conquer and crush the Tartars, those who had killed his

father, escalating over the next twenty years to crush rivals on the steppe, from the Kereyid to the

Naimen.

Jamukha, (chief of the Jadaran, a peer and reported blood brother of Genghis-see above) was finally

defeated in 1205 when a couple of his dissenting followers took him hostage and brought him to the

Mogul Khan. Disapproving of such disloyalty, even to an enemy, Genghis executed the kidnappers

and tried to renew diplomatic relations with Jadaran. Refusing, the Khan was left only with the

option of punishing him, but allowed his old blood-brother one last request. Choosing not to die

through bloodshed, Genghis respected his wishes and had him wrapped in a thick carpet and

crushed to death before burying him.

Having done this, Genghis gained and secured the land which would become Mongolia. By 1206

the assembly had declared him Khaghan or emperor, king of king's and ruler of the Steppes. The

use of this title is disputed however, some claim this was added posthumously, others that it was

attached at the time but not used by Genghis, who remained conscious of his origins and of the need

to remain attached to rather than aloof from his subjects.

With his sovereignty secured, Genghis embarked on an aggressive expansionist foreign policy. In

1207 he sent his son Jochi to suppress Siberia whilst he crossed the Gobi desert to attack the

Tangut, aided by the rivals of this region, the Qarluk and the Uighur. This battle, unlike those the

Mongols were used to was a siege of the city and required a change of military tactics. The sources

tell how Ghenghis cunningly negotiated with the enemies within the walled city, stating if he

received a tribute of one thousand cats and ten thousand swallows his army would retreat. The

tribute received, the Khan then ordered his army to tie cotton to the creatures which were then set

-5-

alight and sent back into the city, throwing the enemies into disarray as the city blazed.

In 1211 Genghis had set his sights on China after hearing from messages in Pekin that a new Kin

emperor Wei-Shao was installed, and declared war on the Jin Kingdom in the North of the country.

The Lhan had prepared well, drawing an army from a 600, 000 square mile radius of his domains

and mobilised all his allies. The Great Wall of China, 2,300 miles of defence, made warfare

difficult, yet Genghis took advantage of this slow progress by concentrating efforts on Manchuria

also. By 1215 Genghis had overwhelmed the great city of Peking (today Beijing).

With his position in the East stable, Genghis Khan turned his attentions to the West. In 1218-9 he

gathered 156, 000-200, 000 troops to attack the Empire of Iran. Under Ala as-Din Muhammad, the

Iranian Empire included Afghanistan and Sagdiana yet was overstretched and consequently weak

enough for an attack by the imperialist Mongols. By 1220 Khan entered Samakand and vanquished

the city, sparing only artisans and Holy men. Within the next couple of years a huge offensive on

Eastern Iran and Afghanistan had been launched, wiping out cities and populations in their wake.

Despite an imperial framework spanning Asia East to West, Genghis Khan was a seasoned warrior

and tactician and knew his limits, deciding against a campaign against the highly complex Indian

principalities to the South of his Empire.

In 1223 an attack had been launched on Multan in Pakistan, yet the heat and difficult, mountainous

terrain had proved overwhelming, and the Mongol armies had retreated.

In the North, West of their territories, the Mongols now turned attention to the Georgian warriors,

then at the height of their glory under Queen Thamar. Victorious, Genghis's armies now emerged

into what is now the Ukraine which was in the hands of the Kipchak Turks. Now began the

tatartchina, the subjugation of the Russians by the Tartar's from the May of 1222.

By the time of its completion, Jebei, one of the Khan's most successful warriors and Subotai had

travelled 12,500 miles in 4 years and vanquished 5 great peoples.

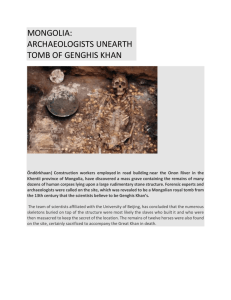

Genghis Khan launched one last campaign as his health faded. In the winter of 1225-6 he crossed

the Gobi desert to march against the Tangut, dying as he saw them slaughtered by his armies in

1227. He was almost 70. His body was marched back to his homeland in Mongolia by his army and

buried anonymously in the soil of the steppe, no plaque or tombstone marking his grave. The area

surrounding the secret grave, the Ikh Khorig (Great Taboo) was then sealed off, only members of

his family and an army trained to kill intruders could enter the area. It remained this way for almost

800 years.

Political administration:

In the hostile environment of the Mongolian plains, Genghis Khan brought a new componentdiscipline.

Although more than competent in warfare, the Mongols had little experience in governance,

essential to the sustained order of their new territories. Quickly, the Mongols recruited foreigners as

bureaucrats, initially from the Tangut of the South, who had adopted a complicated script from the

Chinese, also from the Uighurs and Khitans. As the empire expanded this came to include Iranian's,

Chinese and Syrian's. By 1220 in Sogdiana Genghis had installed offices to maintain records,

establish a census, levy taxes and recruit soldiers and workers.

The census was important in establishing and consolidating the boundaries of each tribes suzerainty.

Genghis Khan fostered peace through increased communication and negotiation across his

territories. In the early 1220's he forged paths through the previously inhospitable ranges of

Afghanistan and Khorasan, aiming to placate the rebels by reaching them.

-6-

Equality before the law was equal, regardless of social standing, and thus the subjects of the Empire

were in theory able to keep check of corruption or misappropriation of funds.

Law:

Together with his Uighur advisor Tatatungo Genghis Khan, shortly after becoming sovereign,

produced the Yasak, a codified law which applied indiscriminately to all Mongols. This is also

know as The Great Law of Genghis Khan, the most important of which was the belief in equality

before the law. Unlike many great law codes in history, this one did not claim authority from God,

but was a deliberate attempt to consolidate the traditions and customs of the herding tribes of the

region, whilst eradicating the aspects which had made these tribes so divided.

For example, the kidnapping of women as brides was outlawed, perceived by the Khan as a

fundamental source of animosity amongst tribes.

This law code included both matters of the state such as a decree of the death penalty for any man

found in communication with a foreign monarch, to simple measures such as prohibiting cattle

drinking from wells. There were also some general principles such as respecting and upholding

religious toleration. Similarly, slavery was outlawed for any Mongol.

Similarly, Genghis defined the role of women in society through recognising their rights and duties

before the law. Women became responsible for familial possessions, freeing up men for war and

combat training.

The yasak bound the Mongul people into a cohesive unit, making one last provision, that on the

death of the Khaghan, the princes of the family should gather together and choose a successor.

This period is commonly thought of as a time of peace across the region, when banditry was

seriously depleted, and is attributed to Genghis Khan and the yasak.

Religious beliefs:

The Mongols were practitioners of shamanism. They believed in a single God- Tengris, whose

power manifested through secondary divinities on earth and could be communicated with through

magic and mystical means. This was the role of the shaman, an intermediary between man and the

gods. Mongols turned to the Shaman on all important occasions, to give advice about the future,

such as the fate of a new born child, to pacify against evil spirits, as master of the ceremonies at

feats and to prevent droughts and storms, and crucially, to achieve military success.

Under Genghis Khan the most influential Shaman amongst the Mogols was Kokochu, the son of

Yisugei's servant who had saved Genghis' life when he was a boy.

They mostly rejected world religions, although they tolerated them and in particular instances

converted.. Interdenominational conferences were held, Buddhism and Christianity allowed to

flourish. To remote all religions, the Khan exempted all religious leaders from taxation and public

service.

This toleration extended also to ethnicity. Although the Mongol race was effectively created over

this period, it was not exalted above other races. Indeed, in the Golden Horde particularly the

Mongols became largely Turkified. Nowhere did they impose their own language universally.

Legacy of Genghis Khan:

Conscious of the need for strong leadership after his death, the Khan divided his Empire into

several Khanates between his four sons, Ogedei, Chagatai, Tolui and Jochi (although Jochi, his first

born, died a few months before the Khan himself and so his lands were split between his sons, Batu

and Orda). Ogedei was designated Great Khan, and the others were to be subordinate to him. For

more on this see Genghis' Successors page.

-7-

The most important aspect of Genghis' rule was his ability to unify, organise and discipline the

fragmented and anarchic Mongol nation.

Trade increased personal as well as state wealth, and for the majority of people a better standard of

life was enjoyed, with gold embroidered clothes and a surplus of food much of which traversed the

plains and was brought from the corners of the empire.

Migration of traders also brought new skills and crafts such as silk production to the Mongols.

The penalty for this increased prosperity came in the form of a highly militarised state, in which a

large proportion of the male population was engaged in warfare, often posted out to other parts of

the empire.

Similarly, taxation took its toll on the ordinary people who often supported an extensive

bureaucracy with a surplus of food and goods and crucially horses and supplies for the courier

service.

Gradually, the constraints of military organisation began to erode the freedom of the Mongol

traditional way of life.

A class of bureaucrats and educated men developed, often marked out from society by their ability

to read and write in the Uighur script.

The severity of law and punishment brought a certain security in public and private life to

Mongolians, which in turn attracted greater international trade.

Regionally, Genghis transformed the small civilizations which characterised the region and began

the creation of nations-large polities and social organisations. He created the trade and

communication links between Europe and China, a crucial moment in world history.

Importantly, the legacy of the Empire has been politicised by posterity. In the 14th and 15th

centuries, The Mongols were viewed in Europe as proponents of civilization, dispersing language,

religion, architecture and technology around the world. By the 18th and 19th centuries the Mongols

had been reconfigured as barbarous, lusting only gold, women and blood. Similarly, the advent of

scientific methods and an obsession with eugenics, led Western Europe to consider the Mongols a

backwards, genetically retarded race.

The man himself has become Divine in Mongolian history, illustrated best by the 'Mausoleum of

Genghis Khan' ('Lords Enclosure'), a shrine in the province of Inner Mongolia.

Many have argued that Genghis is THE most important man in history, transcending the likes of

Columbus and Vasco de Gama, who were only encouraged to the East for its wealth as reported by

travellers such as Marco Polo, who had recorded the treasures of the Great Empire.

There has also been much speculation regarding the genetic legacy of the leader. DNA studies have

suggested that hundreds of thousands of the population of central Asia could be descendants of the

man, who could have had as many as 200 children.

-8-

Mongol Empire in 1227, at Genghis Khan's death. (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Genghis_Khan)

Genghis Facts:

Genghis conquered more land than any other individual in history: 11-12 million square

miles at its zenith.( roughly the size of Africa)

The Mongol army subjugated more people in 25 years than the Roman army did in 400

Genghis was afraid of dogs as a child, according to The Secret History.

Genghis created the first international postal system

The last ruling descendent of Genghis was Alim Khan, emir of Bukhara, who remained in

power in Uzbekistan until 1920.

The Mongols are not renowned for creating great buildings, castles or palaces, but Genghis

probably built more bridges than any other leader in history.

Geoffrey Chaucer devoted the longest story of The Canterbury Tales to Genghis Khan.

Genghis Khan refused to sit for paintings, the only images of the Khan in circulation today

being posthumous Chinese paintings.

At birth, Genghis is reported to ave held in his right hand a blood clot from his mother's

womb. This has been interpreted by the Mongols as a sign of an eventful life, disputably a

curse or an omen.

None of Genghis's generals deserted him in six decades as a warrior, nor did the Khan

punish any.

Summary Timeline:

1155-1167—Temüjin born in Hentiy, Mongolia.

at the age of nine—Temüjin's father Yesükhei poisoned by the Tatars, leaving him and his

family destitute

c. 1184—Temüjin's wife Börte kidnapped by Merkits; calls on blood brother Jamuka and

Wang Khan (Ong Khan) for aid, and they rescued her.

c. 1185—First son Jochi born, leading to doubt about his paternity later among Genghis'

children, because he was born shortly after Börte's rescue from the Merkits.

1190—Temüjin unites the Mongol tribes, becomes leader, and devises code of law Yassa.

1201—Wins victory over Jamuka's Jadarans.

1202—Adopted as Ong Khan's heir after successful campaigns against Tatars.

1203—Wins victory over Ong Khan's Keraits. Ong Khan himself is killed by accident by

allied Naimans.

1204—Wins victory over Naimans (all these confederations are united and become the

Mongols).

1206—Jamuka is killed. Temüjin given the title Genghis Khan by his followers in Kurultai

(around 40 years of age).

1207-1210—Genghis leads operations against the Western Xia, which comprises much of

northwestern China and parts of Tibet. Western Xia ruler submits to Genghis Khan. During

this period, the Uyghurs also submit peacefully to the Mongols and became valued

administrators throughout the empire.

1211—After kurultai, Genghis leads his armies against the Jin Dynasty that ruled northern

China.

1215—Beijing falls, Genghis Khan turns to west and the Khara-Kitan Khanate.

1219-1222—Conquers Khwarezmid Empire.

1226—Starts the campaign against the Western Xia for forming coalition against the

-9-

Mongols, being the second battle with the Western Xia.

1227—Genghis Khan dies leading fight against Western Xia. How he died is uncertain,

although legend states that he was thrown off his horse in the battle, and contracted a deadly

fever soon after.

References:

Peter Brent, 'The Mongol Empire' London, Weidenfield and Nicholson.1976

Jean-Paul Roux 'Genghis Khan and the Mongol Empire' New York, Abrams Publishing. 2003

Paul Ratchnevsky 'Genghis Khan: His life and legacy' Oxford, Blackwell. 1992

Jack Weatherford, 'Genghis Khan and the making of the Modern World'. New York, Three Rivers

Press. 2004

John Mann, 'Kublai Khan: The Mongol King who remade China'. London, Bantam. 2006.

' Genghis Khan: Life, death and resurrection'. London, Bantam. 2004.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Genghis_Khan

'The religion of Genghis Khan' E. Dora Earthy. Numen, vol,2 No. 3 1955. Available on jstor, short

summary of religious beliefs and social divisions in Mongol Empire.

-10-