Contemporary Ethical Theory

advertisement

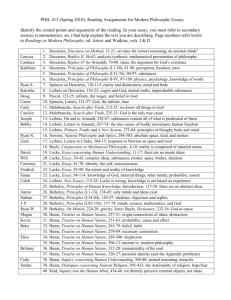

Hume’s Epistemological and Social Conservatism Philosophy 520 Fall 2007 W 2 – 4:30 John Dreher MHP 211 x05173 dreher@usc.edu Hours: Mon 10:30 – 11:30 Fri 10:00 – 11:00 Materials: Below are the main readings for the course. Other readings will be added as the need for them arises. REQUIRED 1. Baier, A., A Progress of Sentiments, Harvard, Harvard University Press, 1991, ISBN: 0-674-71385-0. 2. Coleman, D., ‘Hume, Miracles and Lotteries’ (Hume Studies 14:2, 1988), pp. 328 – 346. 3. Garrett, D., Cognition and Commitment in Hume’s Philosophy, New York and Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1997, ISBN: 0-19-515959-4. 4. Hume, D., N. K. Smith, editor, Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion, Bobbs-Merrill (@ Thomas Nelson and Sons, 1947), New York, 1979 (A used copy may be purchased through the internet. The bookstore has a generic version in stock, without the introductory material by Kemp Smith.) 5. Hacking, I., The Emergence of Probability, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1975, ISBN: 0 521 21460 7. 6. Hume, D., Enquiries Concerning Human Understanding and the Concerning the Principles of Morals, third edition, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1975, ISBN: 0-19-824536-X. 7. Hume, D., Treatise of Human Nature, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1975, ISBN: 0-19-824588-2. RECOMMENDED 1. Loeb, L, Stability and Justification in Hume’s Treatise, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2002, ISBN 0-19-514658-1. 2. J.L. Mackie, Hume’s Moral Theory, London, Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1980, ISBN 0 7100 0525 3 Pbk. 3. Owen, David, Hume’s Reason, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1999, ISBN 0-19-925260-2. 4. Sturgeon, N, ‘Moral Skepticism and Moral Naturalism in Hume’s Treatise,’ Hume Studies, (4:1, 2001). 2 Description: Hume’s theory of belief formation and change enables him to define a method by which to assess ‘moral theories’ that is structurally similar to the method by which he thinks that we judge scientific theories. His theory of belief formation includes the relations of cause and effect, resemblance and contrariety. Although this way of expressing the set-up of the discussion may seem quaint and even antiquated, it is remarkably modern in scope and power. According to Hume, causal hypotheses of the form “All C are E” are tested by identifying or producing antecedent conditions that resemble C. Resemblance is a matter for intuition and therefore an object of knowledge and certainty. Moreover, according to Hume, whether the predicted effect occurs or does not is a matter of contrariety, and thus can be known with certainty. However, all sorts of complicating factors and even hidden causes can spoil apparently satisfactory experiments. Thus, Hume writes that every experiment that we perform ‘may be consider’d as a kind of chance’ and a contrary experiment may produce an imperfect belief by ‘weakening habit’ or by reconstituting the previous causal belief, for example, by identifying a hidden or overlooked dissimilarities in the causes and therefore modifying the original causal hypothesis. (Treatise, p. 135f.) This model of accommodation and recalcitrant experience leads to an epistemological conservatism in Hume that is similar to the conservatism found in Quine. Belief modification is slow because it must take into account the fact that not all salient factors may be apparent in identifying possible initial conditions. This leads Hume to develop a theory of mistaken belief, which he calls ‘unphilosophical probability’ and which arises when people do not assess probability ‘philosophically,’ but rather overlook complicating factors of the sort I have indicated. Unphilosophical probability accounts for prejudice and superstition. Hume is famously a critic of much formal education, of religion and of pseudoscience concerning social matters, and yet Hume’s social views have seemed disappointing and backwards to many commentators. For example, he sees the primary function of justice to preserve property and to guarantee rights of property transference; he identifies remarkable asymmetries between the obligations of women and men. What is there in Hume’s theory of belief formation and revision that accounts for this conservatism with respect to justice and his radical views about education and religion? All are deeply entrenched, having survived centuries of criticism. In this seminar we shall try to determine whether or not his Hume’s social and moral criticism are consistent with his theory of belief modification, which is epistemologically conservative, or whether they go beyond his theory of belief formation in ways that perhaps undermine the symmetry he sees in belief accommodation in the natural and moral sciences. All this will involve a discussion of Hume’s views of religion, of education and of the ‘artificial’ virtues, like justice, chastity, modesty, which involve conventional components. In general, the question that I am asking is whether or not what I shall call Hume’s critical conservatism concerning social issues is consistent with his epistemological conservatism. My answer will be that the two are consistent, and in fact that his social views actually depend upon his epistemology. 3 Requirements: The requirements for the seminar are regular attendance and a substantial paper that stands alone as a unified and complete philosophical piece (as opposed, for example, to a chapter of a proposed dissertation). Please identify your topic by Wednesday October the 3rd. Please turn in a first draft of the paper by Wednesday October the 31st. The final draft of the paper is due on Wednesday December the 12th. Please do not request a grade of ‘IN” unless you have been ill or have faced a genuine personal emergency or crisis. Schedule of Readings and Due Dates: 1. Wed Aug 29: Introductory Remarks and Presuppositions of Hume’s Theory Cognition: The Copy Principle, the Separability Principle Readings: Treatise, pp. 1 – 25, 69 – 77. Garrett, pp. 1 – 28, 41 – 49, 58 – 65. 2. Wed Sep 5: Philosophical Relations, ‘Commitment’ to Causal Inference Readings: Treatise, pp. 69 – 83. Loeb, pp. 1 - 59 Owen, pp. 83 - 112 3. Wed Sep 12: Belief I: The Nature of Belief, Dependency upon the Relations of Cause and Effect and of Resemblance, Probability of Chances and Probability of Causes Readings: Treatise, pp. 84 – 143 (with special attention to the footnote on p. 96.) Garrett, pp. 76 – 95. Hacking, pp. 122 - 42 Loeb, pp. 60 – 100. Owen, pp. 113 – 46, 147 - 74 4. Wed Sep 19: Belief II: Probability of Causes Readings: Hacking, pp. 176 – 85. 5. Wed Sep 26 Unphilosophical Probability I Readings: Treatise, pp. 101 – 138 Loeb, pp. 101 – 38 4 6. Wed Oct 3: TERM PAPER TOPIC IDENTIFIED Unphilosophical Probability II Readings: Loeb, pp. 230 – 52. 7. Wed Oct 10: Skepticism Readings: Treatise, pp. 173 – 218 Garrett, pp. 205 - 242 Loeb, pp. 215 – 229. Owen, pp. 175 – 224. 8. Wed Oct 17: REVIEW 9. Wed Oct 24: Miracles, Education and the Testimony of Others Readings: ECHU, pp. 109 – 148. Coleman, ‘Hume, Miracles and Lotteries’ Garrett, pp. 137 – 162. 10. Wed Oct 31: Morality and Reason FIRST DRAFT OF TERM PAPER DUE Treatise, pp. 399 – 454 J.L. Mackie, pp. 1 - 63 N. Sturgeon, 3 – 84. 11. Wed Nov 7: Moral Judgment READINGS Treatise, pp. 455 – 576 J. L. Mackie, 64 – 75. 12. Wed Nov 14: The Natural Virtues READINGS Treatise, pp. 574 – 618 ECPM Baier, 102 – 219. Mackie, 120 - 219 13. Wed Nov 21: Convention and the Artificial Virtues I 5 Treatise, pp. 477 – 533. Baier, pp. 100-255. Mackie, pp. 76 - 119 14. Wed Nov 28: Convention and the Artificial Virtues II Treatise, pp. 534 – 573. 15. Wed Dec 5: Epistemological and Social Conservatism 16. Wed Dec 12: TERM PAPER DUE