Nairobits E-learning > Course 3 > Web Stars > Lesson 6 > Handout

advertisement

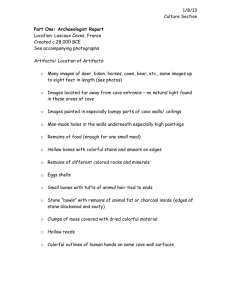

Nairobits E-learning > Course 3 > Web Stars > Lesson 6 > Handout HISTORY OF IMAGES The earliest known forms of imagery were prehistoric paintings. Prehistoric cave paintings required specific artistic skills, but they also served practical purposes. In fact, most paintings prior to 1300 C.E. were needed for a reason, such as to explain hunting techniques or religious ceremonies. An elaborately painted Egyptian tomb featuring a gilded mummy mask served primarily to facilitate the corpse's journey from life on earth to the hereafter. It was decorative, yet practical. Like the Egyptian tomb paintings, most ancient art was left on coffins, walls, wood, and pottery. Not until the Middle Ages (500-1500 C.E.) did anyone think to paint a canvas and frame it. Most painters in the ancient world were craftsmen, similar to goldsmiths, and worked through a royal commission. They did not occupy the same place in society as today's artists, who are often considered daring freethinkers beholden to neither royal rules nor government conventions. In the past, those in charge, rather than the artists themselves, often determined artistic styles. A Survey of Ancient Painting Archaeologists have discovered few paintings from the 20,000 years beginning with the creation of the earliest known cave paintings and concluding with the end of prehistory. Beginning in the 4th century B.C.E., however, early civilizations in the Mediterranean and Europe produced several paintings that have survived until today. In fact, there are so many that art historians and archaeologists have been able to identify styles associated with specific cultures. Remains of enormous sculptures and buildings abound in the ancient world, but the Egyptian civilization was really the first to demonstrate a consistent style in painting. As the longest-running artistic act in the ancient world, the Egyptians sustained a highly recognizable and rigid artistic style for almost 3000 years. Some Egyptian writings and illustrations on papyrus survive today. Most of their paintings, however, can be found only by prying into tombs and temples for a look at the walls. These paintings were often used to decorate and preserve the known world for the afterlife. Beginning around 2800 B.C.E., the Minoan and Mycenaean civilizations in mainland Greece and the Aegean Sea developed another style and purpose for art. Remarkably lively wall paintings, known more commonly as frescoes, survive from c. 1600-1400 B.C.E. in the remains of their palaces and homes. While Egyptian artwork is highly detailed, their figures are still and appear rigid. Minoan art, on the other hand, is extraordinary for its sense of movement and its emphasis on the living world. Out of the Minoan tradition came the development of Greek painting (c. 600100 B.C.E.), which ancient texts describe as unsurpassed in skillful execution. The remains of Greek painting from around 700-500 B.C.E. are scarce and fragmentary. Many works that were painted on wood rotted away, and those on wall frescoes were shattered when the buildings they decorated were destroyed. Indisputably, however, the Greeks of this period made more innovations in painting than any previous civilization and were unchallenged in that respect until the Renaissance. Just as Minoan art inspired Greek art, Greek art strongly shaped Roman art. Roman paintings, mosaics, and manuscripts continued Greek artistic traditions and carried them to the far reaches of the Roman Empire, influencing the Middle East, North Africa, and eventually medieval Europe. With the advent of Christianity, both the Roman Empire and the artistic tendencies of the era underwent a major transformation. Christianity shifted religious emphasis from the body to the soul. Likewise, the emphasis in art moved from the corporeal to the spiritual. The illustration of the Gospels was also necessary in order to spread the beliefs to the new converts, most of whom were illiterate. After the Roman Empire collapsed, Europe's greatest inheritance was the Roman-Christian tradition, which was heavily infused with classical ideas and Christian artistic styles. Despite some scholarly belief that the Middle Ages was a period of artistic decline, the existence of beautiful painted manuscripts and glowing altars from that period suggests otherwise. Painting before 1300 C.E. did not develop in a single, steady progression. Shifting cultural needs and ideas fostered different ideas about what should be painted and how subjects should be rendered. Dabbles on a cave wall or illustrations in a manuscript. These are art. Ancient painting is a reminder that since the beginning of human existence people everywhere feel a need to depict their world. Even before t here was writi ng, the re was art. Prehistoric Painting It's 25,000 B.C.E., give or take a few thousand years. A tribe lives in southern Europe. They have chased some wild animals out of a cave and taken up residence inside. This tribe has fashioned crude clothing from animal pelts and rough tools from stones lying around. The sick and malnourished members of the tribe die young and often violently. Yet, hundreds of feet into the frightening black depths of the cave, in the light of sputtering animal-fat lamps, some members of the tribe are wielding sticks dipped in a mixture of dirt, rocks, and fat, and painting on the rough ceilings and walls. They are creating the earliest surviving paintings produced by humankind. Such works occur not only in one cave, but also in over 130 caves discovered to date. The most notable paintings are found at the caves of Lascaux in southern France and Altamira in northern Spain. What did the earliest artists draw, and what inspired them to do it? These artists depicted what probably mattered most to them: the animals their tribe hunted, including bison, deer, wild boars, and horses. Some of the figures are quite large — one bull at Lascaux is 18 feet long! More surprising is the quality of many drawings: the proportions are correct, the poses are lifelike, and the outlines are firm and vigorous. Figures are occasionally shaded to suggest the roundness of the animal, stippled to indicate the texture of its pelt, and even drawn on a natural protrusion of the rock surface to give its form more fullness. In contrast to the animals, the few human images are small, roughly drawn stick figures, sometimes carrying spears or bows. Why did early humans expend the time and effort to execute these drawings? Archaeologists may never know for sure, but they can fashion educated guesses. Surely, these paintings were not mere wall decorations. ("Gorgar, dear, we could use a nice bison picture over the sleeping straw.") In fact, at Altamira traces of human habitation exist in only one painted room. This separation of living quarters from painted areas suggests that the paintings served a ritual function, either to ensure a good hunt or to promote the fertility of the animals the tribe hunted. Scholars suggest the paintings functioned as a "how-to" guide to hunting. Paintings in which human figures with weapons appear certainly support a connection with the hunt. The fact is, scholars don't know for sure why these prehistoric paintings were created, and it is likely that they never will. Those who study cave paintings don't know how the earliest people believed the world worked, what they hoped for, what they thought controlled life, and what they thought happened after death. Prehistoric means that writing had not been invented yet, so there was no way for early humans to record why they spent time painting. In the end, the full significance of the cave paintings will remain a mystery. Whatever their function in the past, the cave paintings are significant today for the simple, but incredible, fact that they exist. Hunger, cold, wild animals, and even darkness could not deter humans from picking up brushes and depicting their world. You can read much more about the fascinating history of the first form of imagery @ http://www.beyondbooks.com/art11/2.asp There is Egyptian, Roman, Greek…. Art history