CENeer thesis MSWord - DSpace Home

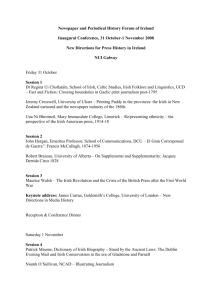

advertisement