Supplementary Information (doc 42K)

advertisement

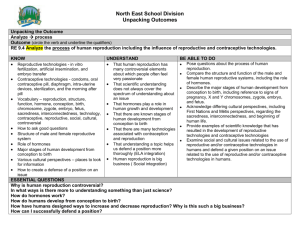

Supplement I 1 Sensitivity analyses methods 2 Examination of the covariate distribution among pregnancies to women with hormonal 3 contraceptive use, as compared to non-users, indicated that women using hormonal contraceptives were 4 generally younger and less likely to be parous than non-users, however these differences varied by 5 contraceptive formulation (Supplementary Table S2). We conducted several sensitivity analyses to 6 address the potential that the estimates observed could be biased from residual confounding resulting 7 from these differences. Specifically, we explored the robustness of our primary results using three 8 different comparator groups, selected to more closely approximate the counterfactual population for 9 exposed pregnancies. These included 1) a comparator group consisting of women without hormonal 10 contraceptive use in early pregnancy and whose pregnancy was reported to be unplanned, to assess for the 11 potential for bias resulting from residual factors associated with having an unplanned pregnancy that are 12 also associated with offspring overweight or obesity, 2) a comparator group of women who were former 13 users of the same contraceptive (within 12 - >4 months before conception), to assess for the potential for 14 confounding by indication -- a bias resulting from factors associated with both the type of hormonal 15 contraceptive prescribed and with offspring overweight or obesity), and 3) an analysis comparing two oral 16 contraceptive groups: combination vs progestin-only, to account for factors associated with oral 17 contraceptive use and childhood overweight that are not related to the particular hormone used. 18 Assuming that any factors contributing to contraceptive failure may be similar for different contraceptive 19 types (and that these factors may also be associated with offspring overweight or obesity), comparison of 20 progestin-only oral contraceptive users as compared to combination oral contraceptive users assesses the 21 potential from bias as result of this unmeasured confounding. 22 In our sensitivity analysis of exposure to hormonal contraceptive use before pregnancy, we 23 evaluated use of the vaginal ring as compared to the combination oral contraceptive. The distribution of 24 study covariates among women obtaining a prescription for the vaginal ring was comparable to the 25 distribution of covariates among women obtaining a prescription for a combination oral contraceptive 26 (Supplementary Table S2). 1 Supplement I 27 Pregnancies with exposure to a hormonal contraceptive within the first 12 weeks after the 28 estimated date of conception were more likely to have been lost to follow-up than pregnancies with no 29 exposure. For example, while 43% of those with no hormonal contraceptive use had data at year 3, 33% 30 of those reporting use of a combination oral contraceptive in early pregnancy were not lost to follow-up 31 (Supplementary Table S3). We conducted additional sensitivity analyses to evaluate the potential for bias 32 through loss to follow-up, first using multiple imputation and second, using inverse probability weighting. 33 We used multiple imputation1 (SAS PROC MI - Monte Carlo Multiple Chain) to impute 10 data sets with 34 imputed covariate and follow-up data. The model results for each data set were then synthesized to obtain 35 final estimates (SAS PROC MIANALYZE). For the inverse probability weighting analysis we 36 constructed weights based on the predicted probability of staying in the study. These were scaled by 37 dividing the marginal probability of staying in the study by the predicted probability.2, 3 38 We also conducted a sensitivity analysis to evaluate the potential for misclassification of 39 exposure. Hormonal contraceptive use was self-reported on the first MoBa questionnaire, with limited 40 detail on type or timing of formulation used. Our own examination of the self-reported data indicated 41 incongruences in the type of formulation used as self-reported compared to the formulation documented 42 as obtained in the NorPD. We identified moderate agreement between self-reported and NorPD-indicated 43 use, for any type of hormonal contraceptive, for each of the exposure periods for which self-reported data 44 was provided (12 months, 4 months, and early pregnancy) (Kappa=0.45 for early pregnancy, 0.60 for use 45 within 4 months of conception, and 0.69 for use within 12 months of conception. As a sensitivity 46 analysis, we characterized self-reported use of a combination type oral contraceptive as those women 47 indicating use of a combination oral contraceptive at the time of conception but for whom the NorPD did 48 not indicate she was using a progestin-only formulation instead. Similarly, for women reporting use of 49 the progestin-only mini pill, we characterized use according to self-report but without inclusion of those 50 pregnancies where the NorPD indicated the formulation used was actually a combination type 51 formulation. In other words, these were women with either no documentation of use in the NorPD at the 52 time of conception (but who did have evidence of having obtained the formulation at another period of 2 Supplement I 53 time within 12 months of conception) or were in agreement with the NorPD that conception occurred 54 while taking the oral contraceptive. 55 Finally, we evaluated the sensitivity of estimates to subtle changes in adjustment sets, including 56 adjustment for maternal diabetes (Type I or II), pre-pregnancy weight versus maternal prepregnancy BMI, 57 income, and age -- more finely characterized in 5, versus 10, age group increments. We also assessed 58 whether a log-binomial model, for estimating relative risks, generated estimates that were materially 59 different from estimates obtained in the logit model estimating odds ratios. 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 1. Greenland S, Finkle WD. A Critical Look at Methods for Handling Missing Covariates in Epidemiologic Regression Analyses. American Journal of Epidemiology 1995; 142(12): 1255-1264. 2. Weuve J, Tchetgen EJT, Glymour MM, Beck TL, Aggarwal NT, Wilson RS et al. Accounting for Bias Due to Selective Attrition The Example of Smoking and Cognitive Decline. Epidemiology 2012; 23(1): 119-128. 3. Hernan MA, Hernandez-Diaz S, Robins JM. A structural approach to selection bias. Epidemiology 2004; 15(5): 615-25. 3