Учебник скачан с сайта www.filologs.ru Contents Preface 7

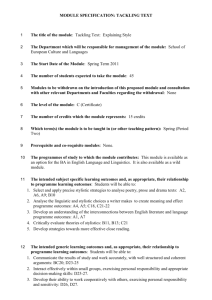

advertisement

Учебник скачан с сайта www.filologs.ru

Contents

Preface........................................................................................ 7

Chapter 1. The Object of Stylistics ..........................................

9

1.1. Problems of stylistic research .................................

9

1.2. Stylistics of language and speech ...........................

14

1.3. Types of stylistic research and branches of stylistics

16

1.4. Stylistics and other linguistic disciplines ................

19

1.5. Stylistic neutrality and stylistic colouring ..............

20

1.6. Stylistic function notion ......................................

24

Practice Section...............................................................

28

Chapter 2. Expressive Resources of the Language ...................

33

2.1. Expressive means and stylistic devices ...................

34

2.2. Different classifications of expressive means ....

37

2.2.1. Hellenistic Roman rhetoric system ..............

39

2.2.2. Stylistic theory and classification of expresssive

means by G. Leech .......................................

45

Учебник скачан с сайта www.filologs.ru

Contents

Contents

2.2.3. I. R. Galperin's classification of expressive means

and stylistic devices .....................................

50

2.2.4. Classification of expressive means and

stylistic devices by Y. M. Skrebnev ...............

57

Practice Section ..............................................................

Chapter 3. Stylistic Grammar...................................................

Chapter 4. The Theory of Functional Styles .............................

122

4.1. The notion of style in functional stylistics ..............

122

4.2. Correlation of style, norm and function in the language

................................................................................ 124

4.3. Language varieties: regional, social, occupational .

128

76

4.4. An overview of functional style systems .................

133

87

4.5. Distinctive linguistic features of the major functional

styles of English ...................................................... 145

3.1. The theory of grammatical gradation. Marked, semimarked and unmarked structures ............................

87

4.5.1. Literary colloquial style ................................ 145

3.2. Grammatical metaphor and types of grammatical

transposition............................................................

4.5.3. Publicist (media) style .................................. 150

89

4.5.2. Familiar colloquial style ............................... 148

4.5.4. The style of official documents .................... 153

3.3. Morphological stylistics. Stylistic potential of the

4.5.5. Scientific/academic style .............................. 155

parts of speech ........................................................

92

3.3.1. The noun and its stylistic potential ..............

92

3.3.2. The article and its stylistic potential.............

95

3.3.3. The stylistic power of the pronoun ..............

97

3.3.4. The adjective and its stylistic functions ...

101

3.3.5. The verb and its stylistic properties .............

103

3.3.6. Affixation and its expressiveness ..................

107

3.4. Stylistic syntax ........................................................

110

Practice Section ..............................................................

116

Practice Section .............................................................. 159

Chapter 5. Decoding Stylistics and Its Fundamental Notions .

162

5.1. Stylistics of the author and of the reader. The notions of

encoding and decoding ........................................... 163

5.2. Essential concepts of decoding stylistic analysis

and types of foregrounding .................................... 166

5.2.1. Convergence ................................................ 169

Учебник скачан с сайта www.filologs.ru

5.2.2. Defeated expectancy .................................. 171

Contents

5.2.3. Coupling .......................................................

173

5.2.4. Semantic field ............................................

176

5.2.5. Semi-marked structures ............................

179

Practice Section ..............................................................

181

Glossary for the Course of Stylistics .........................................

190

Sources.......................................................................................

202

Dictionaries.................................................................................

204

List of Authors and Publications Quoted ..................................

205

Preface

The book suggests the fundamentals of stylistic theory that outline

such basic areas of research as expressive resources of the language,

stylistic differentiation of vocabulary, varieties of the national language

and sociolinguistic and pragmatic factors that determine functional

styles.

The second chapter will take a student of English to the beginnings

of stylistics in Greek and Roman schools of rhetoric and show howmuch modern terminology and classifications of expressive means

owe to rhetoric.

An important part of the book is devoted to the new tendencies and

schools of stylistics that assimilated advancements in the linguistic

science in such trends of the 20"1 century as functional, decoding

and grammatical stylistics.

The material on the wealth of expressive means of English will help

a student of philology, a would-be teacher and a reader of literature

not only to receive orientation in how to fully decode the message of

the work of art and therefore enjoy it all the more but also to improve

their own style of expression.

he chapter on functional styles highlights the importance of «time

a

" place» m language usage. It tells how the same language differs

len used

for different purposes on different occasions in communiation with different people. It explains why we adopt different uses of

Учебник скачан с сайта www.filologs.ru

Preface

language as we go through our day. A selection of distinctive features

of each functional style will help to identify and use it correctly

whether you deal with producing or analysing a text of a certain

functional type.

Chapters on grammar stylistics and decoding stylistics are intended

to introduce the student to the secrets of how a stylistic device works.

Modern linguistics may help to identify the nature and algorithm of

stylistic effect by showing what kind of semantic change, grammatical

transposition or lexical deviation results in various stylistic outcomes.

This book combines theoretical study and practice. Each chapter is

supplied with a special section that enables the student and the teacher

to revise and process the theoretical part by drawing conclusions and

parallels, doing comparison and critical analysis. Another type of practice involves creative tasks on stylistic analysis and interpretation, such

as identifying devices in literary texts, explaining their function and

the principle of performance, decoding the implications they create.

The knowledge of the theoretical background of stylistic research and

the experience of integrating it into one's analytical reading skills

will enhance the competence and proficiency of a future teacher of

English. Working with literary texts on this level also helps to

develop one's cultural scope and aesthetic taste. It will also enrich

the student's linguistic and stylistic thesaurus.

The author owes acknowledgements for the kindly assistance in

reading and stylistic editing of this work to a colleague from the

Shimer College of Chicago, a lecturer in English and American

literature S. Sklar.

Учебник скачан с сайта www.filologs.ru

Chapter 1 The Object of Stylistics

Problems of stylistic research. Stylistics of language and speech.

Types of stylistic research and branches of stylistics. Stylistics

and other linguistic disciplines. Stylistic neutrality and stylistic

coloring. Stylistic function notion.

1.1. Problems of stylistic research

Units of language on different levels are studied by traditional

branches of linguistics such as phonetics that deals with speech

sounds and intonation; lexicology that treats words, their meaning

and vocabulary structure, grammar that analyses forms of words and

their function in a sentence which is studied by syntax. These areas

of linguistic study are rather clearly defined and ave a long-term

tradition of regarding language phenomena from a leve,-oriented point

of view. Thus the subject matter and the material under study of

these linguistic disciplines are more or less clear-cut.

1.1. Problems of stylistic research

Chapter 1. The Object of Stylistics

It gets more complicated when we talk, about stylistics. Some scholars

claim that this is a comparatively new branch of linguistics, which has

only a few decades of intense linguistic interest behind it. The term

stylistics really came into existence not too long ago. In point of fact

the scope of problems and the object of stylistic study go as far back

as ancient schools of rhetoric and poetics.

The problem that makes the definition of stylistics a curious one deals

both with the object and the material of studies. When we speak of the

stylistic value of a text we cannot proceed from the level-biased

approach that is so logically described through the hierarchical system

of sounds, words and clauses. Not only may each of these linguistic

units be charged with a certain stylistic meaning but the interaction of

these elements, as well as the structure and composition of the whole

text are stylistically pertinent.

Another problem has to do with a whole set of special linguistic

means that create what we call «style». Style may be belles-letters or

scientific or neutral or low colloquial or archaic or pompous, or a

combination of those. Style may also be typical of a certain writerShakespearean style, Dickensian style, etc. There is the style of the j

press, the style of official documents, the style of social etiquette and

even an individual style of a speaker or writer—his idiolect.

Stylistics deals with styles. Different scholars have defined style

differently at different times. Out of this variety we shall quote the

most representative ones that scan the period from the 50ies to the

90ies of the 20<л century.

In 1955 the Academician V.V.Vinogradov defined style as «socially

recognized and functionally conditioned internally united totality of

the ways of using, selecting and combining the means of lingual

Учебник скачан с сайта www.filologs.ru

ourse in the sphere of one national language or another...» /о

73) In 1971 Prof- J- R- Galperin offered his definition of style s a

system of interrelated language means which serves a definite aim in

communication.» (36, p. 18).

According to Prof. Y. M. Skrebnev, whose book on stylistics was

published in 1994, «style is what differentiates a group of homogeneous

texts (an individual text) from all other groups (other texts)... Style

can be roughly defined as the peculiarity, the set of specific features

of a text type or of a specific text.» (47, p. 9).

All these definitions point out the systematic and functionally determined character of the notion of style.

The authors of handbooks on German (E. Riesel, M. P. Bran-des),

French (Y. S. Stepanov, R. G. Piotrovsky, K. A. Dolinin), English (I.

R. Galperin, I. V. Arnold, Y. M. Skrebnev, V. A. Maltsev, V. A.

Kukharenko, A. N. Morokhovsky and others) and Russian (M. N.

Kozhina, I. B. Golub) stylistics published in our country over the

recent decades propose more or less analogous systems of styles

based on a broad subdivision of all styles into two classes: literary

and colloquial and their varieties. These generally include from three

to five functional styles.

Since functional styles will be further specially discussed in a separate

chapter at this stage we shall limit ourselves to only three popular

viewpoints in English language style classifications.

rof

' LR-Galperin distinguishes 5 groups of functional styles for the

written variety of language while Prof. I.V.Amold suggests only two

ajor types of styles - colloquial and literary bookish — with their

«пег division into substyles (see chapter 4.4).

Chapter 1. The Object of Stylistics ___________

Prof. Y. M. Skrebnev suggests a most unconventional viewpoint on

the number of styles. He maintains that the number of sublanguages

and styles is infinite (if we include individual styles, styles mentioned

in linguistic literature such as telegraphic, oratorical, reference book,

Shakespearean, short story, or the style of literature on electronics,

computer language, etc.).

1.1. Problems of stylistic research

The aesthetic function of language is an immanent part of works

of art—poetry and imaginative prose but it leaves out works of

science, diplomatic or commercial correspondence, technical

instructions and many other types of texts.

Of course the problem of style definition is not the only one stylistic

research deals with.

2 Expressive means of language are mostly employed in types of

speech that aim to affect the reader or listener: poetry, fiction,

oratory, and informal intercourse but rarely in technical texts or

business language.

Stylistics is that branch of linguistics, which studies the principles, and

effect of choice and usage of different language elements in rendering

thought and emotion under different conditions of communication.

Therefore it is concerned with such issues as

3. It is due to the possibility of choice, the possibility of using

synonymous ways of rendering ideas that styles are formed. With

the change of wording a change in meaning (however slight it

might be) takes place inevitably.

1)

2)

3)

4)

5)

6)

the aesthetic function of language;

expressive means in language;

synonymous ways of rendering one and the same idea;

emotional colouring in language;

a system of special devices called stylistic devices;

the splitting of the literary language into separate systems called

style;

7) the interrelation between language and thought;

8) the individual manner of an author in making use of the language

(47, p. 5).

These issues cover the overall scope of stylistic research and can only

be representative of stylistics as a discipline of linguistic study taken

as a whole. So it should be noted that each of them is concerned

with only a limited area of research:

12

Учебник скачан с сайта www.filologs.ru

4. The emotional colouring of words and sentences creates a certain

stylistic effect and makes a text either a highly lyrical piece of

description or a satirical derision with a different stylistic value.

However not all texts eligible for stylistic study are necessarily

marked by this quality.

5. No work of art, no text or speech consists of a system of stylistic

devices but there's no doubt about the fact that the style of

anything is formed by the combination of features peculiar to it,

that whatever we say or write, hear or read is not style by itself

but has style, it demonstrates stylistic features.

Any national language contains a number of*sublanguages» or

microlanguages or varieties of language with their own specific

eatures, their own styles. Besides these functional styles that are

oted in the norm of the language there exist the so-called «substandard» types of speech such as slang, barbarisms, vulgarisms,

taboo and so on.

1.2. Stylistics of language and speech

Chapter 1. The Object of Stylistics

8. We can hardly object to the proposition that style is also above |

other things the individual manner of expression of an author in

his use of the language. At the same time the individual manner

can only appear out of a number of elements provided by the

common background and employed and combined in a specific |

manner.

language is a mentally organised system of linguistic units. An ъ0

.. aj speaker never uses it. When we use these units we mix

m in acts of speech. As distinct from language speech is not relv

mental phenomenon, not a system but a process of combining these

linguistic elements into linear linguistic units that are called

syntagmatic.

The result of this process is the linear or syntagmatic combination of

vowels and consonants into words, words into word-combinations

and sentences and combination of sentences into texts. The word

«syntagmatic» is a purely linguistic term meaning a coherent sequence

of words (written, uttered or just remembered).

Thus speaking of stylistics as a science we have to bear in mind that

the object of its research is versatile and multi-dimensional and the

study of any of the above-mentioned problems will be a fragmentary

description. It's essential that we look at the object of stylistic study

in its totality.

StyUstics is a branch of linguistics that deals with texts, not with the

system of signs or process of speech production as such. But within

these texts elements stylistically relevant are studied both

syntagmatically and paradigmatically (loosely classifying all stylistic

means paradigmatically into tropes and syntagmatically into figures

of speech).

7. Interrelation between thought and language can be described щ

terms of an inseparable whole so when the form is changed a

change in content takes place. The author's intent and the forms

he uses to render it as well as the reader's interpretation of it is

the subject of a special branch of stylistics—decoding stylistics.

1.2. Stylistics of language and speech

One of the fundamental concepts of linguistics is the dichotomy of

«language and speech» (langue—parole) introduced by F. de Saussure.

According to it language is a system of elementary and complex signsphonemes, morphemes, words, word combinations, utterances and

combinations of utterances. Language as such a system exists m

human minds only and linguistic forms or units can be systematise"

into paradigms.

Учебник скачан с сайта www.filologs.ru

Eventually this brings us to the notions of stylistics of language and

stylistics of speech. Their difference lies in the material studied. the

stylistics of language analyses permanent or inherent stylistic

roperties of language elements while the stylistics of speech studies

stylistic properties, which appear in a context, and they are called

adherent.

WOrds ike тол

'

мач, штудировать, соизволять or English these

' comprehend, lass are bookish or archaic and of the^6 the'r

inherent

Properties. The unexpected use of any ProperT W°rdS '" 3 modem

context wil

> be an adherent stylistic

word''

prevaricate

Chapter 1. The Object of Stylistics

Types of stylistic research and branches of stylistics

So stylistics of language describes and classifies the inherent stylistic

colouring of language units. Stylistics of speech studies the compost,

tion of the utterance—the arrangement, selection and distribution of

different words, and their adherent qualities.

. Various literary genres. ,

The writer's outlook.

Comparative stylistics

1.3. Types of stylistic research and branches of

stylistics

Comparative stylistics is connected with the contrastive study of more

than one language.

Literary and linguistic stylistics

It analyses the stylistic resources not inherent in a separate language

but at the crossroads of two languages, or two literatures and is

obviously linked to the theory of translation.

According to the type of stylistic research we can distinguish literary

stylistics and lingua-stylistics. They have some meeting points or

links in that they have common objects of research. Consequently

they have certain areas of cross-reference. Both study the common

ground of:

Decoding stylistics

1) the literary language from the point of view of its variability;

2) the idiolect (individual speech) of a writer;

3) poetic speech that has its own specific laws.

The points of difference proceed from the different points of analysis.

While lingua-stylistics studies

• Functional styles (in their development and current state).

• The linguistic nature of the expressive means of the language,

their systematic character and their functions.

Literary stylistics is focused on

• The composition of a work of art.

Учебник скачан с сайта www.filologs.ru

A comparatively new branch of stylistics is the decoding stylistics,

which can be traced back to the works of L. V. Shcherba, B. A. Larin,

M. Riffaterre, R. Jackobson and other scholars of the Prague linguistic

circle. A serious contribution into this branch of stylistic study was

also made by Prof. I. V. Arnold (3, 4). Each act of speech has the

performer, or sender of speech and the recipient. The former does the

act of encoding and the latter the act of decoding the information.

f we analyse the text from the author's (encoding) point of view we

should consider the epoch, the historical situation, the personal

Political, social and aesthetic views of the author.

J

' we try to treat the same text from the reader's angle of view max"

haVS t0 disre ard

8 ^s background knowledge and get the sitio mUm ltlformation

from

the text itself (its vocabulary, compose ' sen,ence arrangement,

etc.). The first approach manifests -valence of the literary analysis.

The second is based almost

Chapter 1. The Object of Stylistics

1.4. Stylistics and other linguistic disciplines

exclusively on the linguistic analysis. Decoding stylistics is an attempt

to harmoniously combine the two methods of stylistic research and

enable the scholar to interpret a work of art with a minimum loss of

its purport and message.

Functional stylistics

Special mention should be made of functional stylistics which is a

branch of lingua-stylistics that investigates functional styles, that is

special sublanguages or varieties of the national language such as

scientific, colloquial, business, publicist and so on.

However many types of stylistics may exist or spring into existence

they will all consider the same source material for stylistic analysissounds, words, phrases, sentences, paragraphs and texts. That's why

any kind of stylistic research will be based on the level-forming

branches that include:

Stylistic lexicology

Stylistic Lexicology studies the semantic structure of the word and

the interrelation (or interplay) of the connotative and denotative

meanings of the word, as well as the interrelation of the stylistic

connotations of the word and the context.

Stylistic Phonetics (or Phonostylistics) is engaged in the study of styleforming phonetic features of the text. It describes the prosodic features

of prose and poetry and variants of pronunciation in different types of

speech (colloquial or oratory or recital).

Учебник скачан с сайта www.filologs.ru

Stylistic grammar

Stylistic Morphology is interested in the stylistic potentials of specific

grammatical forms and categories, such as the number of the noun,

or the peculiar use of tense forms of the verb, etc.

Stylistic Syntax is one of the oldest branches of stylistic studies that

grew out of classical rhetoric. The material in question lends itself

readily to analysis and description. Stylistic syntax has to do with the

expressive order of words, types of syntactic links (asyndeton,

polysyndeton), figures of speech (antithesis, chiasmus, etc.). It also

deals with bigger units from paragraph onwards.

1.4. Stylistics and other linguistic disciplines

As is obvious from the names of the branches or types of stylistic

studies this science is very closely linked to the linguistic disciplines

philology students are familiar with: phonetics, lexicology and

grammar due to the common study source.

Stylistics interacts with such theoretical discipline as semasiology. This

is a branch of linguistics whose area of study is a most complicated

and enormous sphere—that of meaning. The term semantics is also

widely used in linguistics in relation to verbal meanings. Semasiology

in its turn is often related to the theory of signs in general and deals

with visual as well as verbal meanings.

Meaning is not attached to the level of the word only, or for that

matter to one level at all but correlates with all of them—morphemes,

words, phrases or texts. This is one of the most challenging areas of

Chapter 1. The Object of Stylistics

1.5. Stylistic neutrality and stylistic colouring

research since practically all stylistic effects are based on the interplay

between different kinds of meaning on different levels. Suffice it to

say that there are numerous types of linguistic meanings attached to

linguistic units, such as grammatical, lexical, logical, denotative,

connotative, emotive, evaluative, expressive and stylistic.

Most scholars abroad and in this country giving definitions of style

come to the conclusion that style may be defined as deviation from

the lingual norm. It means that what is stylistically conspicuous,

stylistically relevant or stylistically coloured is a departure from the

norm of a given national language. (G. Leech, M. Riffaterre, M.

Halliday, R.Jacobson and others).

Onomasiology (or onomatology) is the theory of naming dealing with

the choice of words when naming or assessing some object or

phenomenon. In stylistic analysis we often have to do with a transfer

of nominal meaning in a text (antonomasia, metaphor, metonymy,

etc.)

The theory of functional styles investigates the structure of the

national linguistic space—what constitutes the literary language, the

sublanguages and dialects mentioned more than once already.

Literary stylistics will inevitably overlap with areas of literary studies

such as the theory of imagery, literary genres, the art of composition,

etc.

Decoding stylistics in many ways borders culture studies in the broad

sense of that word including the history of art, aesthetic trends and

even information theory.

1.5. Stylistic neutrality and stylistic colouring

Speaking of the notion of style and stylistic colouring we cannot

avoid the problem of the norm and neutrality and stylistic colouring in

contrast to it.

Учебник скачан с сайта www.filologs.ru

There are authors who object to the use of the word «norm» for various

reasons. Thus Y. M. Skrebnev argues that since we acknowledge the

existence of a variety of sublanguages within a national language we

should also acknowledge that each of them has a norm of its own. So

the sentence «I haven't ever done anything» (or «I don't know

anything») as juxtaposed to the sentence «I ain't never done nothing»

(«I don't know nothing») is not the norm itself but merely conforms

to the literary norm.

The second sentence («I ain't never done nothing») most certainly

deviates from the literary norm (from standard English) but if fully

conforms to the requirements of the uncultivated part of the English

speaking population who merely have their own conception of the

norm. So Skrebnev claims there are as many norms as there are

sublanguages. Each language is subject to its own norm. To reject

this would mean admitting abnormality of everything that is not

neutral. Only ABC-books and texts for foreigners would be

considered «normal». Everything that has style, everything that

demonstrates peculiarities of whatever kind would be considered

abnormal, including works by Dickens, Twain, O'Henry, Galsworthy

and so on (47, pp. 21-22).

For all its challenging and defiant character this argument seems to

contain a grain of truth and it does stand to reason that what we

_____________ Chapter 1. The Object of Stylistics

1.5. Stylistic neutrality and stylistic colouring

often call «the norm» in terms of stylistics would be more appropriate

to call «neutrality».

Since style is the specificity of a sublanguage it is self-evident that

non-specific units of it do not participate in the formation of its style;

units belonging to all the sublanguages are stylistically neutral. Thus

we observe an opposition of stylistically coloured specific elements to

stylistically neutral non-specific elements.

The stylistic colouring is nothing but the knowledge where, in what

particular type of communication, the unit in question is current. On

hearing for instance the above-cited utterance «I don't know nothing»

(«I ain't never done nothing») we compare it with what we know

about standard and non-standard forms of English and this will

permit us to pass judgement on what we have heard or read.

Professor Howard M. Mims of Cleveland State University did an

accurate study of grammatical deviations found in American English

that he terms vernacular (non-standard) variants (44). He made a list

of 20 grammatical forms which he calls relatively common and some

of them are so frequent in every-day speech that you hardly register

them as deviations from the norm, e. g. They ready to go instead of

They are ready to go; Joyce has fifty cent in her bank account instead

of Joyce has fifty cents in her bank account; My brother, he's a doctor

instead of My brother is a doctor, He don't know nothing instead of He

doesn't know anything.

The majority of the words are neutral. Stylistically coloured wordsbookish, solemn, poetic, official or colloquial, rustic, dialectal,

vulgar—have each a kind of label on them showing where the unit

was «manufactured», where it generally belongs.

Учебник скачан с сайта www.filologs.ru

Within the stylistically coloured words there is another opposition

between formal vocabulary and informal vocabulary.

These terms have many synonyms offered by different authors. Roman

Jacobson described this opposition as casual and non-casual, other

terminologies name them as bookish and colloquial or formal and

informal, correct and common.

Stylistically coloured words are limited to specific conditions of

communication. If you isolate a stylistically coloured word it will still

preserve its label or «trade-mark» and have the flavour of poetic or

artistic colouring.

You're sure to recognise words like decease, attire, decline (a proposal)

as bookish and distinguish die, clothes, refuse as neutral while such

units as snuff it, rags (togs), turn down will immediately strike you as

colloquial or informal.

In surveying the units commonly called neutral can we assert that

they only denote without connoting? That is not completely true.

If we take stylistically neutral words separately, we may call them

neutral without doubt. But occasionally in a certain context, in a

specific distribution one of many implicit meanings of a word we

normally consider neutral may prevail. Specific distribution may also

create unexpected additional colouring of a generally neutral word.

Such stylistic connotation is called occasional.

Stylistic connotations may be inherent or adherent. Stylistically

coloured words possess inherent stylistic connotations. Stylistically

neutral words will have only adherent (occasional) stylistic connotations acquired in a certain context.

Chapter 1. The Object of Stylistics

1.6. Stylistic function notion

A luxury hotel for dogs is to be opened at Lima, Peru a city of 30.000

dogs. The furry guests will have separate hygienic kennels, top medical

care and high standard cuisine, including the best bones. (Mailer)

Accordingly stylistics is first and foremost engaged in the study of

connotative meanings.

Two examples from this passage demonstrate how both stylistically

marked and neutral words may change their colouring due to the

context:

cuisine -»inherently formal (bookish, high-flown);

-» adherent connotation in the context—lowered/humorous;

bones -» stylistically neutral;

-4 adherent connotation in the context—elevated/humorous.

In brief the semantic structure (or the meaning) of a word roughly

consists of its grammatical meaning (noun, verb, adjective) and its

lexical meaning. Lexical meaning can further on be subdivided into

denotative (linked to the logical or nominative meaning) and

connotative meanings. Connotative meaning is only connected with

extra-linguistic circumstances such as the situation of communication

and the participants of communication. Connotative meaning consists

of four components:

1) emotive;

2) evaluative;

1.6. Stylistic function notion

3) expressive;

4) stylistic.

Like other linguistic disciplines stylistics deals with the lexical,

grammatical, phonetic and phraseological data of the language.

However there is a distinctive difference between stylistics and the

other linguistic subjects. Stylistics does not study or describe separate

linguistic units like phonemes or words or clauses as such. It studies

their stylistic/unction. Stylistics is interested in the expressive potential

of these units and their interaction in a text.

Stylistics focuses on the expressive properties of linguistic units,

their functioning and interaction in conveying ideas and emotions in

a certain text or communicative context.

Stylistics interprets the opposition or clash between the contextual

meaning of a word and its denotative meaning.

Учебник скачан с сайта www.filologs.ru

A word is always characterised by its denotative meaning but not

necessarily by connotation. The four components may be all present

at once, or in different combinations or they may not be found in the

word at all.

1. Emotive connotations express various feelings or emotions. Emotions differ from feelings. Emotions like ./ay, disappointment, pleasure,

anger, worry, surprise are more short-lived. Feelings imply a more

stable state, or attitude, such as love, hatred, respect, pride, dignity,

etc. The emotive component of meaning may be occasional or usual

(i.e. inherent and adherent).

It is important to distinguish words with emotive connotations from

words, describing or naming emotions and feelings like anger or

Chapter 1. The Object of Stylistics

1.6. Stylistic function notion

fear, because the latter are a special vocabulary subgroup whose

denotative meanings are emotions. They do not connote the speaker's

state of mind or his emotional attitude to the subject of speech.

maintains that emotive connotation always entails expressiveness but

not vice versa. To prove her point she comments on the example by

A. Hornby and R. Fowler with the word «thing» applied to a girl (4,

p. ПЗ).

Thus if a psychiatrist were to say You should be able to control feelings

of anger, impatience and disappointment dealing with a child as a piece

of advice to young parents the sentence would have no emotive

power. It may be considered stylistically neutral.

On the other hand an apparently neutral word like big will become

charged with emotive connotation in a mother's proud description of

her baby: He is a BIG boy already!

2. The evaluative component charges the word with negative, positive,

ironic or other types of connotation conveying the speaker's attitude

in relation to the object of speech. Very often this component is a part

of the denotative meaning, which comes to the fore in a specific

context.

The verb to sneak means «to move silently and secretly, usu. for a

bad purpose» (8). This dictionary definition makes the evaluative

component bad quite explicit. Two derivatives a sneak and sneaky

have both preserved a derogatory evaluative connotation. But the

negative component disappears though in still another derivative

sneakers (shoes with a soft sole). It shows that even words of the

same root may either have or lack an evaluative component in their

inner form.

3. Expressive connotation either increases or decreases the expres

siveness of the message. Many scholars hold that emotive and

expressive components cannot be distinguished but Prof. I.A.Arnold

Учебник скачан с сайта www.filologs.ru

When the word is used with an emotive adjective like «sweet» it

becomes emotive itself: «She was a sweet little thing». But in other

sentences like «She was a small thin delicate thing with spectacles»,

she argues, this is not true and the word «thing» is definitely expressive

but not emotive.

Another group of words that help create this expressive effect are the

so-called «intensifiers», words like «absolutely, frightfully, really,

quite», etc.

4. Finally there is stylistic connotation. A word possesses stylistic

connotation if it belongs to a certain functional style or a specific

layer of vocabulary (such as archaisms, barbarisms, slang, jargon,

etc). Stylistic connotation is usually immediately recognizable.

Yonder, slumber, thence immediately connote poetic or elevated

writing.

Words like price index or negotiate assets are indicative of business

language.

This detailed and systematic description of the connotative meaning

of a word is suggested by the Leningrad school in the works of Prof.

I. V. Arnold, Z. Y. Turayeva, and others.

Galperin operates three types of lexical meaning that are stylistically

relevant—logical, emotive and nominal. He describes the stylistic

Practice Section

Chapter 1. The Object of Stylistics

colouring of words in terms of the interaction of these types of

lexical meaning. Skrebnev maintains that connotations only show to

what part of the national language a word belongs—one of the sublanguages (functional styles) or the neutral bulk. He only speaks

about the stylistic component of the connotative meaning.

Practice Section

1. Comment on the notions of style and sublanguages in the

national language.

2. What are the interdisciplinary links of stylistics and other linguistic subjects such as phonetics, lexicology, grammar, and

semasiology? Provide examples.

How does stylistics differ from them in its subject-matter and

fields of study?

3. Give an outline of the stylistic differentiation of the national

English vocabulary: neutral, literary, colloquial layers of words;

areas of their overlapping. Describe literary and common colloquial stratums of vocabulary, their stratification.

4. How does stylistic colouring and stylistic neutrality relate to

inherent and adherent stylistic connotation?

5. Can you distinguish neutral, formal and informal among the

following groups of words.

Учебник скачан с сайта www.filologs.ru

A

B

C

1.

currency

money

dough

2.

to talk

to converse

to chat

3.

to chow down

to eat

to dine

4.

to start

5.

insane

nuts

6.

spouse

hubby

7.

to leave

8.

geezer

9.

veracious

10.

mushy

to commence

to kick off

mentally ill

husband

to withdraw

senior citizen

opens

emotional

to shoot off

old man

sincere

sentimental

6. What kind of adherent stylistic meaning appears in the otherwise

neutral word feeling?

I've got no feeling paying interest, provided that it's reasonable. (Shute)

I've got no feeling against small town life. I rather like it. (Shute)

7. To what stratum of vocabulary do the words in bold type in

the following sentences belong stylistically? Provide neutral or

colloquial variants for them:

/ expect you've seen my hand often enough coming out with the grub.

(Waugh)

She betrayed some embarrassment when she handed Paul the tickets,

and a hauteur which subsequently made her feel very foolish. (Cather)

Chapter 1. The Object of Stylistics

I must be off to my digs. (Waugh)

When the old boy popped off he left Philbrick everything, except a few

books to Grade. (Waugh)

He looked her over and decided that she was not appropriately dressed

and must be a fool to sit downstairs in such togs. (Cather)

It was broken at length by the arrival of Flossie, splendidly attired in

magenta and green. (Waugh)

8. Consider the following utterances from the point of view of the

grammatical norm. What elements can be labelled as deviations

from standard English? How do they comply with the norms of

colloquial English according to Mims and Skrebnev?

Sita decided that she would lay down in the dark even if Mrs. Waldvogel

came in and bit her. (Erdrich)

Always popular with the boys, he was, even when he was so full he

couldn't hardly fight. (Waugh)

Practice Section

Make up lists of words that create this tenor in the texts given

below.

Whilst humble pilgrims lodged in hospices, a travelling knight would

normally stay with a merchant. (Rutherfurd)

Fo' what you go by dem, eh? W'y not keep to yo'self? Dey don' want

you, dey don' care fo'you. H' ain'you got no sense? (Dunbar-Nelson)

They sent me down to the aerodrome next morning in a car. I made a

check over the machine, cleaned filters, drained sumps, swept out the

cabin, and refuelled. Finally I took off at about ten thirty for the

short flight down to Batavia across the Sunda straits, and found the

aerodrome and came on to the circuit behind the Constellation of K. L.

M. (Shute)

We ask Thee, Lord, the old man cried, to look after this childt. Fatherless he is. But what does the earthly father matter before Tliee? The

childt is Thine, he is Thy childt, Lord, what father has a man but Thee?

(Lawrence)

/ wouldn't sell it not for a hundred quid, I wouldn't. (Waugh)

-We are the silver band the Lord bless and keep you, said the

stationmaster in one breath, the band that no one could beat whatever

but two indeed in the Eisteddfod that for all North Wales was look you.

There was a rapping at the bedroom door. «I'll learn that Luden Sorrels

to tomcat.» (Chappel)

I see, said the Doctor, I see. That's splendid. Well, will you please go

into your tent, the little tent over there.

...he used to earn five pound a night... (Waugh)

9. How does the choice of words in each case contribute to the

stylistic character of the following passages? How would you

define their functional colouring in terms of technical, poetic,

bookish, commercial, dialectal, religious, elevated, colloquial,

legal or other style?

Учебник скачан с сайта www.filologs.ru

To march about you would not like us? Suggested the stationmaster, we

have a fine flaglook you that embroidered for us was in silks. (Waugh)

The evidence is perfectly clear. The deceased woman was unfaithful to

her husband during his absence overseas and gave birth to a child out

of wedlock.

Chapter 1. The Object of Stylistics

Her husband seemed to behave with commendable restraint and wrote

nothing to her which would have led her to take her life... The deceased

appears to have been the victim of her own conscience and as the time

for the return of her husband drew near she became mentally upset. Fi

find that the deceased committed suicide while the balance of her mind\

was temporarily deranged. (Shute)

/ say, I've met an awful good chap called Miles. Regular topper. You\

know, pally. That's what I like about a really decent party—you meet]

such topping fellows. I mean some chaps it takes absolutely years tot

know, but a chap like Miles I feel is a pal straight away. (Waugh)

She sang first of the birth of love in the hearts of a boy and a girl. And

on the topmost spray of the Rose-tree there blossomed a marvellous rose,

petal following petal, as song followed song. Pale was it, at first as the

mist that hangs over the river—pale as the feet of the morning. (Wilde) ;

He went slowly about the corridors, through the writing—rooms, smoking- j

rooms, reception-rooms, as though he were exploring the chambers of

an enchanted palace, built and peopled for him alone.

When he reached the dining-room he sat down at a table near a window. \

The flowers, the white linen, the many-coloured wine-glasses, the gay \

toilettes of the women, the low popping of corks, the undulating repetitions i

of the Blue Danube from the orchestra, all flooded Paul's dream with

bewildering radiance. (Cather)

Chapter 2

Expressive Resources of the Language

Expressive means and stylistic devices. Different classifications

of expressive means and stylistic devices from antique to modern

times.

In my reading of modern French novels I

had acquired the habit of underlining expressions, which struck me as aberrant from

general usage, and it often happened that the

underlined passages taken together seemed

to offer a certain consistency. I wondered if

it would be possible to establish a common

denominator for all or most of these deviations, could we find a common spiritual

etymon or the psychological root of 'several'

individual 'traits of style' in a writer.

Leo Spitzer. Linguistics and Literary History

Учебник скачан с сайта www.filologs.ru

Chapter 2. Expressive Resources of the Language

2.1. Expressive means and stylistic devices

2.1. Expressive means and stylistic devices

Stylistic devices

Expressive means

A stylistic device is a literary model in which semantic and structural

features are blended so that it represents a generalised pattern.

Expressive means of a language are those linguistic forms and

properties that have the potential to make the utterance emphatic or

expressive. These can be found on all levels—phonetic, graphical,

morphological, lexical or syntactical.

Expressive means and stylistic devices have a lot in common but

they are not completely synonymous. All stylistic devices belong to

expressive means but not all expressive means are stylistic devices.

Phonetic phenomena such as vocal pitch, pauses, logical stress, and

drawling, or staccato pronunciation are all expressive without being

stylistic devices

Morphological forms like diminutive suffixes may have an expressive effect: girlie, piggy, doggy, etc. An unexpected use of the

author's nonce words like: He glasnosted his love affair with th:

movie star (People) is another example of morphological expressive

means.

Lexical expressive means may be illustrated by a special group о

intensifiers—awfully, terribly, absolutely, etc. or words that retain thei

logical meaning while being used emphatically: // was a very sped e

vening/event/gift.

There are also special grammatical forms and syntactical patterns

attributing expressiveness, such as: / do know you! I'm really angry

with that dog of у ours! That you should deceive me! If only I could help

you!

Учебник скачан с сайта www.filologs.ru

Prof. I. R. Galperin calls a stylistic device a generative model when

through frequent use a language fact is transformed into a stylistic

device. Thus we may say that some expressive means have evolved into

stylistic devices which represent a more abstract form or set of forms.

A stylistic device combines some general semantic meaning with a certain linguistic form resulting in stylistic effect. It is like an algorithm

employed for an expressive purpose. For example, the interplay, interaction, or clash of the dictionary and contextual meanings of words

will bring about such stylistic devices as metaphor, metonymy or irony.

The nature of the interaction may be affinity (likeness by nature),

proximity (nearness in place, time, order, occurrence, relation) or

contrast (opposition).

Respectively there is metaphor based on the principle of affinity,

metonymy based on proximity and irony based on opposition.

The evolution of a stylistic device such as metaphor could be seen from

four examples that demonstrate this linguistic mechanism (interplay of

dictionary and contextual meaning based on the principle of affinity):

1. My new dress is as pink as this flower: comparison (ground for

comparison—the colour of the flower).

2. Her cheeks were as red as a tulip: simile (ground for simile—

colour/beauty/health/freshness)

3. She is a real flower: metaphor (ground for metaphor—frail/

fragrant/tender/beautifu 1/helpless...).

Chapter 2. Expressive Resources of the Language

My love is a red, red rose: metaphor (ground for metaphor—

passionate/beautiful/strong...).

4. Ruby lips, hair of gold, snow-white skin: trite metaphors so

frequently employed that they hardly have any stylistic power

left because metaphor dies of overuse. Such metaphors are aiso

called hackneyed or even dead.

A famous literary example of an author's defiance against immoderate \

use of trite metaphors is W. Shakespeare's Sonnet 130

My mistress' eyes are nothing like the sun;

Coral is far more red than her lips' red;

If snow be white, why then her breasts are dun;

If hairs be wires, black wires grow on her head.

I have seen roses damasked, red and white,

But no such roses see I in her cheeks;

And in some perfumes is there more delight

Than in the breath that from my mistress reeks.

I love to hear her speak, yet well I know

That music hath a far more pleasing sound;

I grant I never saw a goddess go;

My mistress, when she walks, treads on the ground.

And yet, by heaven, I think my love as rare

As any she belied with false compare.

The more unexpected, the less predictable is the ground for comparison the more expressive is the metaphor which in this case got a

special name of genuine or authentic metaphor. Associations suggested by the genuine metaphor are varied, not limited to any definite

number and stimulated by the individual experience or imagination.

Учебник скачан с сайта www.filologs.ru

2.2. Different classifications of expressive means

2.2. Different classifications of expressive means

In spite of the belief that rhetoric is an outmoded discipline it is in

rhetoric that we find most of the terms contemporary stylistics

generally employs as its metalanguage. Rhetoric is the initial source

of information about metaphor, metonymy, epithet, antithesis, chiasmus, anaphora and many more. The classical rhetoric gave us still

widely used terms of tropes and figures of speech.

That is why before looking into the new stylistic theories and findings

it's good to look back and see what's been there for centuries. The

problems of language in antique times became a concern of scholars

because of the necessity to comment on literature and poetry. This

necessity was caused by the fact that mythology and lyrical poetry was

the study material on which the youth was brought up, taught to read

and write and generally educated. Analysis of literary texts helped to

transfer into the sphere of oratorical art the first philosophical notions

and concepts.

The first linguistic theory called sophistry appeared in the fifth century

В. С Oration played a paramount role in the social and political life

of Greece so the art of rhetoric developed into a school.

Antique tradition ascribes some of the fundamental rhetorical notions to the Greek philosopher Gorgius (483-375 В. С). Together

with another scholar named Trasimachus they created the first

school of rhetoric whose principles were later developed by Aristotle

(384-322 В. С.) in his books «Rhetoric» and «Poetics».

Aristotle differentiated literary language and colloquial language. This

first theory of style included 3 subdivisions:

2.2. Different classifications of expressive means

Chapter 2. Expressive Resources of the Language

• the choice of words;

2.2.1- Hellenistic Roman rhetoric system

• word combinations;

Tropes:

• figures.

1. The choice of words included lexical expressive means such as

foreign words, archaisms, neologisms, poetic words, nonce

words and metaphor.

2. Word combinations involved 3 things:

a) order of words;

b) word-combinations;

c) rhythm and period (in rhetoric, a complete sentence).

3. Figures of speech. This part included only 3 devices used by the

antique authors always in the same order.

a) antithesis;

b) assonance of colons;

c) equality of colons.

A colon in rhetoric means one of the sections of a rhythmical period

in Greek chorus consisting of a sequence of 2 to 6 feet.

Later contributions by other authors were made into the art of

speaking and writing so that the most complete and well developed

antique system, that came down to us is called the Hellenistic Roman

rhetoric system. It divided all expressive means into 3 large groups:

Tropes, Rhythm (Figures of Speech) and Types of Speech.

A condensed description of this system gives one an idea how much

we owe the antique tradition in modern stylistic studies.

Учебник скачан с сайта www.filologs.ru

1. Metaphor—the application of a word (phrase) to an object

(concept) it doesn't literally denote to suggest comparison with

another object or concept.

E. g. A mighty Fortress is our God.

2. Puzzle (Riddle)—a statement that requires thinking over a confusing or difficult problem that needs to be solved.

3. Synecdoche—the mention of a part for the whole.

E. g. A fleet of 50 sail, (ships)

4. Metonymy—substitution of one word for another on the basis

of real connection.

E.g. Crown for sovereign; Homer for Homer's poems; wealth for rich

people.

5. Catachresis—misuse of a word due to the false folk etymology

or wrong application of a term in a sense that does not belong

to the word.

E. g. Alibi for excuse; mental for weak-minded; mutual for common;

disinterested for uninterested.

A later term for it is malapropism that became current due to Mrs.

Malaprop, a character from R. Sheridan's The Rivals (1775). This

sort of misuse is mostly based on similarity in sound.

Chapter 2. Expressive Resources of the Language

E. g. That young violinist is certainly a child progeny (instead of

prodigy).

6. Epithet—a word or phrase used to describe someone or some-1

thing with a purpose to praise or blame.

E. g. ft was a lovely, summery evening.

7. Periphrasis—putting things in a round about way in order to]

bring out some important feature or explain more clearly the

idea or situation described.

E.g. Igot an Arab boy... and paid him twenty rupees a month, about

thirty bob, at which he was highly delighted. (Shute)

8. Hyperbole—use of exaggerated terms for emphasis.

E. g. A 1000 apologies; to wait an eternity; he is stronger than a lion.

9. Antonomasia—use of a proper name to express a general idea

or conversely a common name for a proper one.

E. g. The fron Lady; a Solomon; Don Juan.

2.2. Different classifications of expressive means

E. g. Tip-top, helter-skelter, wishy-washy; oh, the dreary, dreary

moorland.

2. Epenalepsis (polysyndeton) conjunctions: use of several con

junctions.

E. g. He thought, and thought, and thought; f hadn't realized until

then how small the houses were, how small and mean the shops. (Shute)

3. Anaphora: repetition of a word or words at the beginning of two

or more clauses, sentences or verses.

E.g. No tree, no shrub, no blade of grass, not a bird or beast, not even

a fish that was not owned!

4. Enjambment: running on of one thought into the next line,

couplet or stanza without breaking the syntactical pattern.

E.g. fn Ocean's wide domains Half

buried in the sands Lie skeletons

in chains With shackled feet and

hands.

Figures of Speech that create Rhythm

(Longfellow)

These expressive means were divided into 4 large groups:

Figures that create rhythm by means of addition 1. Doubling

(reduplication, repetition) of words and sounds.

Учебник скачан с сайта www.filologs.ru

5. Asyndeton: omission of conjunction.

E.g. He provided the poor with jobs, with opportunity, with self-respect.

_______ Chapter 2. Expressive Resources of the Language

Figures based on compression

1. Zeugma (syllepsis): a figure by which a verb, adjective or other

part of speech, relating to one noun is referred to another.

E. g. He lost his hat and his temper, with weeping eyes and hearts.

2. Chiasmus—a reversal in the order of words in one of two parallel

phrases.

E. g. He went to the country, to the town went she.

3. Ellipsis—omission of words needed to complete the construction

or the sense.

E.g. Tomorrow at 1.30; The ringleader was hanged and his followers

imprisoned.

Figures based on assonance or accord

1. Equality of colons—used to have a power to segment and

arrange.

2. Proportions and harmony of colons.

Figures based on opposition

1. Antithesis—choice or arrangement of words that emphasises a

contrast.

E. g. Crafty men contemn studies, simple men admire them, wise men

use them; Give me liberty or give me death.

Учебник скачан с сайта www.filologs.ru

2.2. Different classifications of expressive means

2. Paradiastola—the lengthening of a syllable regularly short (in

Greek poetry).

3. Anastrophe—a term of rhetoric, meaning, the upsetting for

effect of the normal order of words (inversion in contemporary

terms).

E. g. Me he restored, him he hanged.

Types of speech

Ancient authors distinguished speech for practical and aesthetic

purposes. Rhetoric dealt with the latter which was supposed to

answer certain requirements, such as a definite choice of words, their

assonance, deviation from ordinary vocabulary and employment of

special stratums like poetic diction, neologisms and archaisms,

onomatopoeia as well as appellation to tropes. One of the most

important devices to create a necessary high-flown or dramatic effect

was an elaborate rhythmical arrangement of eloquent speech that

involved the obligatory use of the so-called figures or schemes. The

quality of rhetoric as an art of speech was measured in terms of

skilful combination, convergence, abundance or absence of these

devices. Respectively all kinds of speech were labelled and represented in a kind of hierarchy including the following types: elevated:

flowery /florid/ exquisite; poetic; normal; dry; scanty; hackneyed;

tasteless.

Attempts to analyse and determine the style-forming features of prose

also began in ancient times. Demetrius of Alexandria who lived in

Greece in the 3d century ВС was an Athenian orator, statesman and

Philosopher. He used the ideas of such earlier theorists as Aristotle

Chapter 2. Expressive Resources of the Language

2.2. Different classifications of expressive means

and characterized styles by rhetoric of purpose that required certain

grammatical constructions.

Dionyssius wrote over twenty books, most famous of which are «On

Imitation», «Commentaries on the Ancient Orators» and «On the

Arrangement of Words». The latter is the only surviving ancient study

of principles of word order and euphony.

The Plain Style, he said, is simple, using many active verbs and

keeping its subjects (nouns) spare. Its purposes include lucidity,

clarity, familiarity, and the necessity to get its work done crisply and

well. So this style uses few difficult compounds, coinages or

qualifications (such as epithets or modifiers). It avoids harsh sounds,

or odd orders. It employs helpful connective terms and clear clauses

with firm endings. In every way it tries to be natural, following the

order of events themselves with moderation and repetition as in

dialogue.

The Eloquent Style in contrast changes the natural order of events to

effect control over them and give the narration expressive power

rather than sequential account. So this style may be called passive in

contrast to active.

As strong assumptions are made subjects are tremendously amplified

without the activity of predication because inherent qualities rather

than new relations are stressed. Sentences are lengthy, rounded, well

balanced, with a great deal of elaborately connected material. Words

can be unusual, coined; meanings can be implied, oblique, and

symbolic. Sounds can fill the mouth, perhaps, harshly.

Two centuries later a Greek rhetorician and historian Dionysius of

Halicarnassus who lived in Rome in the 1*' century ВС characterized

one of the Greek orators in such a way: «His harmony is natural,

stately, spacious, articulated by pauses rather than strongly polished

and joined by connectives; naturally off-balance, not rounded and

symmetrical.» (43, p. 123).

Учебник скачан с сайта www.filologs.ru

For the Romans a recommended proportion for language units in

verse was two nouns and two adjectives to one verb, which they called

«the golden line».

Gradually the choices of certain stylistic features in different combinations settled into three types—plain, middle and high.

Nowadays there exist dozens of classifications of expressive means

of a language and all of them involve to a great measure the same

elements. They differ often only in terminology and criteria of

classification.

Three of the modern classifications of expressive means in the English

language that are commonly recognized and used in teaching stylistics

today will be discussed further in brief.

They have been offered by G. Leech, I. R Galperin and У. M. Skrebnev.

2.2.2. Stylistic theory and classification of

expresssive means by G. Leech

One of the first linguists who tried «to modernize» traditional

rhetoric system was a British scholar G. Leech. In 1967 his

contribution into stylistic theory in the book «Essays on Style a"d

Language» was published in London (39). Paying tribute to lhe

descriptive linguistics popular at the time he tried to show

Chapter 2. Expressive Resources of the Language

2.2. Different classifications of expressive means

how linguistic theory could be accommodated to the task ofj

describing such rhetorical figures as metaphor, parallelism, allit-l

eration, personification and others in the present-day study ofj

literature.

According to Leech the literary work of a particular author must be

studied with reference to both—«dialect scale» and «register scale».

Proceeding from the popular definition of literature as the creative use

of language Leech claims that this can be equated with the use of

deviant forms of language. According to his theory the] first principle

with which a linguist should approach literature isj the degree of

generality of statement about language. There are] two particularly

important ways in which the description of language entails

generalization. In the first place language operates by what may be called

descriptive generalization. For example, a grammarian may! give

descriptions of such pronouns as /, they, it, him, etc. as objective

personal pronouns with the following categories: first/third person,

singular/plural, masculine, non-reflexive, animate/inanimate.

Although they require many ways of description they are all pronouns

and each of them may be explicitly described in this fashion.

The other type of generalization is implicit and would be appropriate in

the case of such words as language and dialect. This sort of description

would be composed of individual events of speaking, writing, hearing

and reading. From these events generalization may cover the linguistic

behaviour of whole populations. In this connection Leech maintains 1

the importance of distinguishing two scales in the language. He calls

them «register scale» and «dialect scale». «Register scale» distinguishes

spoken language from written language, the language of respect from

that of condescension, advertising from science, etc. The term covers

linguistic activity within society. «Dialect scale» differentiates

language of people of different age, sex, social strata, geographical

area or individual linguistic habits (ideolect).

Учебник скачан с сайта www.filologs.ru

The notion of generality essential to Leech's criteria of classifying

stylistic devices has to do with linguistic deviation.

He points out that it's a commonplace to say that writers and poets

use language in an unorthodox way and are allowed a certain degree

of «poetic licence». «Poetic licence» relates to the scales of descriptive

and institutional delicacy.

Words like thou, thee, thine, thy not only involve description by

number and person but in social meaning have «a strangeness value»

or connotative value because they are charged with overtones of piety,

historical period, poetics, etc.

The language of literature is on the whole marked by a number of

deviant features. Thus Leech builds his classification on the principle

of distinction between the normal and deviant features in the language

of literature.

Among deviant features he distinguishes paradigmatic and syntagmatic

deviations. All figures can be initially divided into syntagmatic or

paradigmatic. Linguistic units are connected syntagmatically when

they combine sequentially in a linear linguistic form.

Paradigmatic items enter into a system of possible selections at one

Point of the chain. Syntagmatic items can be viewed horizontally,

Paradigmatic—vertically.

Paradigmatic figures give the writer a choice from equivalent items,

which are contrasted to the normal range of choices. For instance,

certain nouns can normally be followed by certain adverbs, the choice

Chapter 2. Expressive Resources of the Language

dictated by their normal lexical valency: inches/feet/yard ~r away, e.

g. He was standing only a few feet away.

However the author's choice of a noun may upset the normal system

and create a paradigmatic deviation that we come across in literary

and poetic language: farmyards away, a grief ago, all sun long.

Schematically this relationship could look like this

inches

normal away

inches

feet

yards

farmyard

feet

deviant away

normal

away

yards farmyard deviant

away

The contrast between deviation and norm may be accounted for by

metaphor which involves semantic transfer of combinatory links.

Another example of paradigmatic deviation is personification. In this

case we deal with purely grammatical oppositions of personal/

impersonal; animate/inanimate; concrete/abstract.

This type of deviation entails the use of an inanimate noun in a

context appropriate to a personal noun.

As Connie had said, she handled just like any other aeroplane, except that

she had better manners than most. (Shute). In this example she stands

for the aeroplane and makes it personified on the grammatical level.

Учебник скачан с сайта www.filologs.ru

The deviant use of she in this passage is reinforced by the collocation

with better manners, which can only be associated with human beings.

2.2. Different classifications of expressive means

aeroplane normal inanimate neuter

it

train

car

aeroplane

deviant animate female

she

aeroplane

train

normal inanimate neuter

car aeroplane

it

deviant animate female

she

This sort of paradigmatic deviation Leech calls «unique deviation»

because it comes as an unexpected and unpredictable choice that

defies the norm. He compares it with what the Prague school of

linguistics called «foregrounding».

Unlike paradigmatic figures based on the effect of gap in the expected

choice of a linguistic form syntagmatic deviant features result from

the opposite. Instead of missing the predictable choice the author

imposes the same kind of choice in the same place. A syntagmatic

chain of language units provides a choice of equivalents to be made

at different points in this chain, but the writer repeatedly makes the

same selection. Leech illustrates this by alliteration in the furrow

followed where the choice of alliterated words is not necessary but

superimposed for stylistic effect on the ordinary background.

This principle visibly stands out in some tongue-twisters due to the

deliberate overuse of the same sound in every word of the phrase. So

Учебник скачан с сайта www.filologs.ru

instead of a sentence like "Robert turned over a hoop in a circle" we

nave the intentional redundancy of "r" in "Robert Rowley rolled a

round roll round".

Basically the difference drawn by Leech between syntagmatic and

Paradigmatic deviations comes down to the redundancy of choice in

the first case and a gap in the predicted pattern in the second.

Chapter 2. Expressive Resources of the Language

This classification includes other subdivisions and details that cannot

all be covered here but may be further studied in Leech's book.

This approach was an attempt to treat stylistic devices with reference

to linguistic theory that would help to analyse the nature of stylistic

function viewed as a result of deviation from the lexical and

grammatical norm of the language.

2.2. Different classifications of expressive means

3) rhyme (full, incomplete, compound or broken, eye rhyme,

internal rhyme. Also, stanza rhymes: couplets, triple, cross,

framing/ring);

4) rhythm.

2. Lexical expressive means and stylistic devices

2.2.3. I. R. Galperfn's classification of expressive means and

stylistic devices

The classification suggested by Prof. Galperin is simply organised and

very detailed. His manual «Stylistics» published in 1971 includes the

following subdivision of expressive means and stylistic devices based

on the level-oriented approach:

1. Phonetic expressive means and stylistic devices.

2. Lexical expressive means and stylistic devices.

3. Syntactical expressive means and stylistic devices*.

There are three big subdivisions in this class of devices and they all

deal with the semantic nature of a word or phrase. However the

criteria of selection of means for each subdivision are different and

manifest different semantic processes.

I. In the first subdivision the principle of classification is the interaction of different types of a word's meanings: dictionary, contextual,

derivative, nominal, and emotive. The stylistic effect of the lexical

means is achieved through the binary opposition of dictionary and

contextual or logical and emotive or primary and derivative meanings

of a word.

1. Phonetic expressive means and stylistic devices To

A. The first group includes means based on the interplay of dictionary

and contextual meanings:

this group Galperin refers such means as:

metaphor: Dear Nature is the kindest Mother still. (Byron)

1) onomatopoeia (direct and indirect): ding-dong; silver bells... tinkle, tinkle;

2) alliteration (initial rhyme): to rob Peter to pay Paul;

' To avoid repetition in each classification definitions of all stylistic devices are

given in the glossary

Учебник скачан с сайта www.filologs.ru

metonymy:

The camp, the pulpit and the law For

rich man's sons are free.

(Shelly)

Chapter 2. Expressive Resources of the Language

2.2. Different classifications of expressive means

irony: // must be delightful to find oneself in a foreign country without

a penny in one's pocket.

II. The principle for distinguishing the second big subdivision according to Galperin is entirely different from the first one and is

based on the interaction between two lexical meanings simultaneously materialised in the context. This kind of interaction helps to call

special attention to a certain feature of the object described. Here

belong:

B. The second unites means based on the interaction of primary and

derivative meanings:

polysemy: Massachusetts was hostile to the American flag, and she

would not allow it to be hoisted on her State House;

zeugma and pun: May's mother always stood on her gentility; and Dot's

mother never stood on anything but her active little feet. (Dickens)

C. The third group comprises means based on the opposition of

logical and emotive meanings:

interjections and exclamatory words:

All present life is but an interjection

An 'Oh' or 'Ah' of joy or misery,

Or a 'Ha! ha!' or 'Bah!'-a yawn or 'Pooh!'

Of which perhaps the latter is most true.

(Byron)

simile: treacherous as a snake, faithful as a dog, slow as a tortoise.

periphrasis: a gentleman of the long robe (a lawyer); the fair sex.

(women)

euphemism: In private I should call him a liar. In the Press you should

use the words: 'Reckless disregard for truth'. (Galsworthy)

hyperbole: The earth was made for Dombey and Son to trade in and

the sun and the moon were made to give them light. (Dickens)

Ш. The third subdivision comprises stable word combinations in

their interaction with the context:

cliches: clockwork precision, crushing defeat, the whip and carrot policy.

epithet: a well-matched, fairly-balanced give-and-take couple. (Dickens)

proverbs and sayings: Come! he said, milk's spilt. (Galsworthy)

oxymoron: peopled desert, populous solitude, proud humility. (Byron)

epigrams: A thing of beauty is a joy for ever. (Keats)

D. The fourth group is based on the interaction of logical and nominal

meanings and includes:

Quotations: Ecclesiastes said, 'that all is vanity'. (Byron)

antonomasia; Mr. Facing-Both-Ways does not get very far in this world. I

(The Times)

Учебник скачан с сайта www.filologs.ru

allusions: Shakespeare talks of the herald Mercury. (Byron)

decomposition of set phrases: You know which side the law's buttered.

(Galsworthy)

Chapter 2. Expressive Resources of the Language

2.2. Different classifications of expressive means

3. Syntactical expressive means and stylistic devices

chiasmus: