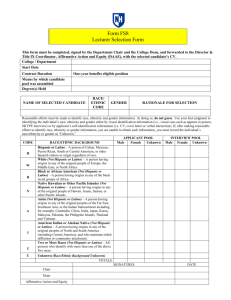

Lynn Stephen`s Teaching Latino Studies - ALLA

advertisement

1 Teaching Latino Studies: Hemispheric Approaches and Embedding Knowledge in Regional Histories Presented at Round Table on “Latino/a Studies in the Next Decade” Annual Meetings of the American Anthropological Association November 17-20, 2010 New Orleans Lynn Stephen Distinguished Professor of Anthropology and Ethnic Studies Director, Center for Latino/a and Latin American Studies University of Oregon stephenl@uoregon.edu Who are we teaching? The state of Oregon, like many states in the U.S. has seen very significant growth in the number of Latino immigrants from the period of 1995- 2005. These immigrants and their children are now in our school systems and have already changed the face of my and many other states. Today I am going to speak from the standpoint of teaching Latino Studies in Anthropology and Ethnic Studies at a public university. My goal is to engage students in a hemispheric model of thinking that embeds Latino history and culture in the larger racial and ethnic history of the West and Northwest and mobilizes regional histories of Latino roots to actively engage students in their own educations. Anthropology offers wonderful tools for doing this through training students as ethnographers, visual anthropologists, and analysts who can be knowledge creators not only for themselves, but for a wider public. In this sense, I feel that public engagement is a form of politics integral to the history of Latino Studies that can be continued through the methods I am going to propose through a concrete course sequence and wider project called Latino Roots in Oregon. The country as a whole will be about 18 percent Latino in ten years. By 2025, half the entering workforce will be Latino. Given that the competitive demands of a global and high tech economy increasingly require college degrees, the underrepresentation of Latinos in higher education is a national crisis. We have to work within our universities to actively recruit, retain, and engage Latino students and also to educate all students about Latino histories, cultures, diversity, and politics. Let’s think ahead to 2020 in Oregon. First, it is likely that Latinos will be about 18 – 22 percent of the population in Oregon. If current trends hold, almost 30 percent of public high school graduates will be Latino. They may call themselves “Chicano,” “Mexicano,” “Latino,” “Hispanic,” “Mixteco, Zapoteco, Purepecha,” (Indigenous ethnic groups from Mexico), and other national origin identities such as “Peruano,” (Peruvian), “Salvadoreño (Salvadoran), “Guatemalteco” (Guatemalan), “Americano,” (American) and more. And they will speak a lot of different languages. Right now we have at least 16 2 different indigenous languages spoken among Latino immigrants, what the U.S. census now calls “Hispanic American Indians.” We will have a lot of new Latino businesses, radio stations, newspapers, television, and everyone will continue to be trying to get a share of the Latino dollar as consumers. In the year 2020 in Oregon and today, Spanish is not a foreign language it is a home language and many people either are or aspire to be bilingual in Spanish and English. Speaking, reading, and writing Spanish is an asset just like speaking reading and writing English is—no matter who you are. So how do we teach in this reality? Comparison and Hemispheric Approaches My Latino Studies teaching has been in the context of both an anthropology department and a Department of Ethnic Studies. In Anthropology, I have embedded my teaching on immigration, farmworkers, Latino social movements, and indigenous immigrants in a context that tries to decenter the Anglo-pioneer historical and cultural discourse which dominates my state and in a broader context of a much longer view of regional histories. In Ethnic Studies, we teach through a comparative approach which examines race and ethnicity in the United States with a primary focus on people of African, Asian, Latina/o, and Native American descent. While we teach particular courses in the field of Latino Studies such as “Chicano/Latino Studies” and topical courses, the theoretical requirements are integrative and include courses such as “Theoretical Perspectives in Ethnic Studies” with an emphasis on concepts and keywords such as” such as “race, ethnicity, white;” “border, naturalization, immigration;” “queer, community body;” “community organizing, resistance;” “gender, performance, identity;” “citizenship, America;” “Indian, nation, colonial/coloniality.” Other required conceptual courses include “Race and Ethnicity” and a senior pro-seminar organized around student research and thesis. The framework students learn about Latino Studies in is comparative with integrative concepts. I have found long views of hemispheric history to be a very important tool for teaching Latino Studies. Pre-colonial native histories, maps, and concepts in what is now the U.S. and Mexico, for example, provides tools for reconceptualizing “America” and who it belongs to. Indigenous maps from the early colonial period reflect a very different conceptualization of the relationships between place, people, and landscape than European maps. 3 Example 1. Teozoacolco Figure 4. Relaciones Geográficas Collection, “Teazocoalco,” map, Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection, http://www.lib.utexas.edu/benson/rg/rg_images4.html Used by permission of the Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection, University of Texas, Austin The map above, of Teozacualco, today known as San Pedro Teozacualco, was created in 1580 in response to a project sponsored by King Phillip II of Spain known as the Relaciones geográficas. The project entailed questionnaires sent around to towns and asked them to respond to fifty questions. Question number ten “asked the respondents to describe ‘the site and location of the said town, if it is situated high or low on a plain, with a picture of the layout and a design of the streets and plazas and other places indicated, including monasteries, as well as can be sketched on a map declaring which part of the town faces north and south.’”i The map of Teozacualco was drawn in response to this question, but represents a very different idea of “mapping” than was perhaps in the minds of those who wrote the instructions. Constructed in the form of a circle, this map uses a radial concept to illustrate 14 churches, a network of roads, rivers, hills, valleys and other natural features, the sociopolitical organization of Teozacualco in relation to 13 other communities, boundaries with other political jurisdictions, and genealogies. The genealogies are of the hereditary rulers from and Teozacoalco and neighboring Tilantongo with the male and female rulers of each couple seated together on a woven reed map, representing a dynastic marriage. The map has script and names in Spanish and Mixtec. Like other Mixtec maps, this one links place names, stories of place founders, and genealogies to landscape and 4 cosmology. There is not a separation between human stories and place stories and the earth. This 1704 map drawn by Giuvanni Francesco Gemelli Careri, is the first published representation of the legendary Aztec migration from Aztlán to Chapultepec Hill, currently Mexico City. The map is supposed to be copied from indigenous sources. It traces the pilgrimage conceptually and features cartographic and spiritual elements with labels in Nahuatl and loose English translations. On May 24, 1065 CE, the Mexica (Aztec) began an epic migration from their ancestral homeland, Aztlan, which translated means “Place of Reeds” or “Place of Egrets”, to the shores of Lake Texcoco, in Mexico’s Central Mesa. There they founded the city of Tenochtitlan. This map offers a valuable conversation point for linking colonialism and Chicano Studies through the Concept of Atzlan. This next map, printed in 1507, is the first world map in which the name "America" appears for the lands of the New World. The compiler of the map, Martin Waldseemüller (1474-1519), was a German-born priest and cartographer. Many people suspect that it was this map that caused the hemisphere to be called “America,” after explorer Amerigo Verspucci. While contemporary Latin Americans are quick to claim an identity as “Americanos” and as living in America, many in the U.S. today are puzzled when others outside the U.S. want to call themselves “Americans” as well. Thinking from the position of the hemisphere and extending the definition of who is “American” as this 1507 map suggests, requires us to suspend our current notions of borders. We must also recognize this map, however, as a basic element of European colonialism. “America” as 5 imagined in Europe is very different from the mapping which indigenous peoples did of those around them and with whom they interacted. Figure 1. Martin Waldseemüller, “Map with America, 1507,” map, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Waldseemuller_map_closeup_with_America.jp g A map of the Viceroyalty of New Spain from 1786 through 1821 provides more familiar outlines of the U.S. as a growing empire perched to absorb the territory of New Spain as its own territory expands westward. This map provides a picture of U.S. empirebuilding which in many ways resembles that of a colonial power-vis-à-vis New Spain. Here, “America” is not claimed as a hemispheric label but as part of “The United States of America,” forming the pivot point for U.S. nationalism and claims to further territory. 6 In addition to the “United States of America,” we see “The Louisiana Purchase,” a series of “intendencies” inside of New Spain’s boundaries which signal future states in independent Mexico and in the territories that the U.S. will usurp from Mexico in 1848. The Province of Texas, the Government of New Mexico, and the Government of New California all portend contested territories. The Vice-Royalty of New Spain spanned from north of the Great Salt Lake including the government of New California, the Government of New Mexico, and the provinces of Texas, Coahuila, and Nuevo Santender which all occupied territory that the U.S. took from Mexico in 1848 Figure 5. Stanley Alan Arbingast, “The Viceroyalty of New Spain, 1786-1821,” map, in Atlas of Mexico (Austin, 1975), 26. Used by permission of the University of Texas, Austin 7 Getting students to think of themselves as members of the American hemisphere which has been re-imagined by Europeans in a different form from Native peoples is a strategy for decentering dominant U.S. historical narratives of expansion and manifest destiny. It also offers, however, the opportunity to confront colonial histories and discourses of discovery and coloniality both in terms of Spain’s colonization of native territories and the U.S.’s imperial process of conquest from the nations of Native peoples, from independent Mexico, and Spain’s Caribbean colonies. Embedding knowledge in local histories, community engagement My final strategy for teaching Latino Studies during the next decades involves using the tools of ethnography and visual anthropology to engage students in researching and telling their own stories of Latino and Latin American immigration, settlement, social movements, and civic and political integration during the 20th century. This history will necessarily be embedded in the larger racial/ethnic and colonial histories of the territory which became “United States of America.” I have been engaged for the past two years in a project titled, “Latino Roots in Oregon.” This project began as an oral history project and museum exhibit that involved five graduate students, two community consultants, myself and another colleague. We collected demographic information, historical information, documented the increase in Latino cultural institutions and businesses, the emergence of religious services in Spanish, and documented on audio and video the stories of nine families of diverse origins. The result was a museum exhibit with 17 panels, video, audio files to listen to, and many display cases of objects. After that we developed a DVD, bilingual short book and prepared the panels for display. Now the materials are being exhibited in other venues. Follow this link to download copies of our bilingual booklet: http://cllas.uoregon.edu/media/publications/ Follow this link to download our bilingual film: http://jcomm.uoregon.edu/publications/latino-roots-in-lanecounty?searchterm=Latino+Roots Follow this link and scroll down to read more: http://cllas.uoregon.edu/ The second part of the project involves a new course sequence at the University of Oregon—“Latino Roots I, Latino Roots II”—to be taught during Winter and Spring 2011 through Anthropology and Journalism and cross-listed with Ethnic Studies and Latin American Studies. Latino Roots I will focus on giving a theoretical, documentary, and ethnographic understanding of the processes of Latino immigration and settlement in Oregon during the past 150 years. Latino Roots II will teach students how to produce a short video documentary from oral history interviews. By learning how to conduct A/V digital oral history interviews, edit, and annotate them, students learn Latino history in a hands-on way while they help build this Latino historical record. The assignments cultivate dialogue among the Latino community 8 and wider public with faculty and students connecting Latino community members and the public to their stories. The final part of the project involves the creation of an open-access digital archive that will incorporate moving images, still photographs, documents, text, and audio files from the original research project and student research. By fall of 2011 we hope to have up the original materials from the museum exhibit digitized, 35-40 stories with audio, video, photographs, and documents as well as other products. Through this project students are creating an open-access resource that can be used for teaching Latino Studies throughout the state and elsewhere. Engagement with the community is an important part of the history of Latino Studies and through this strategy we hope to continue with that political engagement that began with Chicano Studies, Puerto Rican Studies, and other pioneering branches of Latino Studies. i Kevin Terraciano, The Mixtecs of Colonial Mexico: Ñudzahui History, Sixteenth through Eighteenth Centuries (Stanford, 2001), 21.