ExCredit-_Mexican_War_Historiography

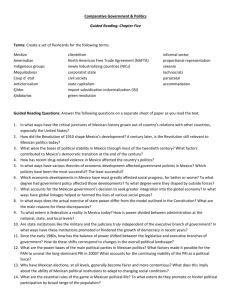

advertisement

How to receive Extra Credit: Read my paper in its entirety. As you read, create a brief outline of my paper. Start your outline by writing my paper’s thesis in your own words, and then finish it with a list of the main topics of each numbered paragraph. A Historiographical Study of the Mexican War Susie VanBlaricum January 12, 2007 History 1629: Professor Johnson Between the years 1846 and 1848 the United States waged a war with Mexico. This war is known by many names; most popular among U.S. historians is “Mexican War,” the name first popularized by contemporary American participants in the war.1 Additional frequently used titles are “Mexican-American War” and “United StatesMexican War.” Still, other historians refer to the war simply as the “conflict of 18461848.” In Mexico, the war has many alternative titles, including the Invasiόn de los Norte 2 . Each nomenclature denotes various perspectives of the war, shifting or balancing blame and responsibility between those involved. For the purpose of this paper, which seeks to outline and discuss the historiography of this conflict as chronicled by writers of United States history, the title “Mexican War” will be used without any presumption as to its meaning or innate bias, but simply because it is the name most popularly used throughout the U.S. histories of the war. While a large body of historical work exists which discusses the conflict from the Mexican perspective, for the purpose of this essay, the perspective of the United States will be privileged. 1) As with any war, there is not one definitive historical work which describes the conflict with perfect and indisputable precision. Since 1848, historians have examined the war using various lenses. Influenced by current events, politics, and personal ideologies, historians have interpreted the war to reflect their own experiences and biases. Additionally, historians have narrowed the lens through which they view history further by choosing to focus on specific aspects of the war. Some of the specific themes Richard Bruce Winders, Mr. Polk’s Army: The American Military Experience in the Mexican War (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1997), xii. 2 Thomas R. Hietala, Manifest Design: American Exceptionalism and Empire, revised edition (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2003), vviii. 1 1 discussed in this paper will include the political, military, social, and cultural histories of the Mexican War. 2) This war, though short, has significantly impacted the history of the United States. The Mexican War represented a number of “firsts” for the U.S. It was the first successful offensive war, the first war fought almost exclusively on foreign soil, and the first occupation of a foreign capital for the U.S.3 With the advent of the steam driven press and the use of instantaneous communication via the telegraph, this was the first war in the history of mankind which pervaded the mass media as news spread swiftly to all regions of the U.S. and allowed virtually everyone to experience the war vicariously through the penny-press.4 In addition to the many “firsts” the war with Mexico represented, the Mexican War is distinguished in history because of the substantial amount of land the U.S. amassed at the war’s conclusion. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hildago put the vast territories of New Mexico and California in the possession of the United States, thus setting the final boundaries of the continental United States (excluding Alaska). 3) Despite the significance of this war in United States history, it has remained a rather unpopular war with historians and the general reading public. As one historian points out, “There are no Mexican War Round Tables, no Mexican War Book Clubs.”5 While the majority of Americans can name a handful of Civil War generals in the blink of an eye, very few outside the historical profession, and some might argue few within the profession, could do the same for the Mexican War. “It has almost become standard for authors writing about the Mexican War to inform readers that the topic has been 3 Otis A. Singletary, The Mexican War (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1960), 3. Walter Johnson, “The Mexican War,” History 1629 Lecture, Harvard University, 15 Nov, 2006. 5 Singletary, The Mexican War, 4. 4 2 neglected,”6 states one historian; and indeed, few histories of the war begin without making reference to the gap in historical literature on the subject. Though this historical gap is dramatically less than it once was, why have historians been so slow to fill it? 4) Many have postulated on why the Mexican War has been so neglected. Some point to the war’s brevity or the fact that the war was rather isolated and never became a “massive affair” or a “total war.” Many blame the simple fact that the Mexican War lives in the shadow of one of the United States’s greatest wars of all time, the Civil War.7 Still, others declare that Americans have been hesitant to dwell on the Mexican War because, as the war is seen by many as a war of conquest, “there has been a certain moral uneasiness about the origins of this war.”8 Unlike the Civil War, few will claim the Mexican War was fought in the name of freedom and justice. Perhaps this last explanation echoes some elements of truth as literature on the war dramatically increased in the wake of the Vietnam Conflict, another war which invokes moral unease among many. Many historians made clear comparisons between the Mexican War and the war in Vietnam. Whatever the reason, the Mexican War has traditionally been, and continues to be, an often overlooked war in the history of the United States. It is this oversight that many of the historians discussed in this paper sought to overcome. 5) Early historians of the Mexican War seemed to be obsessed with placing blame. Their histories are quick to point fingers and declare tyrants and victims in the war. In the earliest histories, personal opinions are not hidden, but blatantly sprawled across the page. Hubert H. Bancroft, who published his six-volume History of Mexico, 1824-1861 in Winders, Mr. Polk’s Army, xi. Singletary, The Mexican War, 4. 8 John D. Eisenhower, “Polk and His Generals,” from Essays on the Mexican War. edited by Douglas W. Richmond (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1986), 4. 6 7 3 the 1880s, makes it abundantly clear that the United States, and the pro-slavery and landhungry men who controlled it, should be held entirely to blame for the war. He states, without subtlety and no shame in name-calling: It was a premeditated and predetermined affair….it was the result of a deliberately calculated scheme of robbery on the part of a superior power. There were at Washington enough unprincipled men high in office…who were only too glad to be able in any way to pander to the tastes of their supporters – there were enough of this class, slave-holders, smugglers, Indian-killers, and foul-mouthed, tobacco-spurting swearers upon sacred Fourth-of-July principles to carry spread-eagle supremacy from the Atlantic to the Pacific, who were willing to lay aside all notions of right and wrong in the matter and unblushingly to take whatever could be secured solely upon the principle of might. Mexico, poor, weak, struggling to secure for herself a place among the nations, is now to be humiliated, kicked, cuffed, and beaten by the bully on her northern border…9 6) James Ford Rhodes followed in the footsteps of Bancroft; however, instead of placing the blame on the United States as a whole, he points his finger firmly at the Southern slave-holding majority. Writing his epic seven-volume work titled History of the United States from the Compromise of 1850, he published his account of the Mexican War in 1893. Rhodes was a Northerner who sympathized with the “old whigs” and “nineteenth century writers who had not forgiven the South for the holocaust of 1861”10 In his mind all the sins of the era were solely in the hands of the South, and thus there too lies the blame for the Mexican War. By his account it was the “aggressive southern slavocracy” who planted the seeds for war when they promoted the annexation of Texas. These “slave power” hungry Southerners then deliberately took advantage of the disputed 9 Hubert H. Bancroft, “The War as an American Plot,” from The Mexican War: Was it Manifest Destiny? edited by Ramon Eduardo Ruiz (Hinsdale, Illinois: The Dryden Press, 1963), 85. 10 Bancroft, “The War as an American Plot,” 3 4 border between Texas and Mexico, and bullied Mexican leaders into war in order to conquer land which they could use to establish even more slave states.11 7) In 1920, one reviewer for the Political Science Quarterly wrote, “If there is one tradition more firmly established than any other in American historical writing, it is that the Mexican War was a disgrace to our country.”12 As shown with the work of Rhodes and Bancroft, it had become custom for historians dealing with the Mexican War to condemn the Polk administration for “bullying poor, weak Mexico into war by its aggressive imperialism in the interest of slavery.”13 Skeptical as to whether or not these early histories were “correct and complete”, Justin H. Smith set out to write his own comprehensive history of the war.14 Smith conducted extensive research for his project. His complete two-volume work published in 1919 is approximately 1200 pages long with 350 of those pages dedicated to notes. Smith made it a point to look at all he could access, and consequently used a majority of sources overlooked by previous historians.15 As Smith boasts in his preface, “probably more than nine-tenths of the material used in the preparation of this work is in fact new. [For example] no previous writer on the subject had been through the diplomatic and military archives of either belligerent nation.”16 8) Smith’s extensive research led him to form a new and dramatically different conclusion about the war. “As a particular consequence of this full inquiry, an episode that has been regarded both in the United States and abroad as discreditable to us, appears Bancroft, “The War as an American Plot,” 9. David S. Muzzey, “Review of The War with Mexico, by Justin H. Smith,” Political Science Quarterly 35, no. 4 (December 1920): 646. 13 Muzzey, “Review of The War with Mexico, by Justin H. Smith,” 646. 14 Justin H. Smith, The War with Mexico, vol. I, (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1919), x. 15 Muzzey, “Review of The War with Mexico, by Justin H. Smith,” 646. 16 Smith, The War with Mexico, viii. 11 12 5 now to wear quite a different complexion.”17 In response to prior historians’ shouts of “Blame America!”, “Blame Polk!”, and “Blame the South!”, Smith argued that we should “Blame Mexico!” Smith argues that America is not to be held responsible for the war and, instead, all responsibility lies with Mexico. As Smith wrote, “No other course than that taken by Polk would have been patriotic or even rational.”18 Published at the close of the First World War, a period of high nationalism, Smith’s nationalistic theme was adored by reviewers. One reviewer wrote, “Those students of American history who, like the reviewer, have been unwilling to accept the traditional interpretation of the Mexican War as a disgraceful episode in our country’s annals, will derive comfort from Professor Smith’s volumes. And those who are still minded to cast the blame….will find it difficult to deal with material which the author furnishes…”19 9) While Smith’s two-volume work remained the definitive work on the Mexican War for many decades (one history, publishing in 1960, began his “Suggested Reading” with the affirmation, “By far the best general account of the war is Justin H Smith’s twovolume The War with Mexico”20), mid-twentieth century historians began to take a renewed interest in the war as they sought to fill the void of scholarly works on the subject. These historians sought to write summaries of the war, pieces that provided background information without too much in-depth analysis of one particular aspect of the war. Seeing the war as being unjustly neglected, Otis Singletary published his summary of the war, titled appropriately, The Mexican War, in 1960. As he states in his prologue, his short work will fulfill its purpose “if it succeeds in conveying to the reader 17 Smith, The War with Mexico, ix. Muzzey, “Review of The War with Mexico, by Justin H. Smith,” 650. 19 Muzzey, “Review of The War with Mexico, by Justin H. Smith, 650-651. 20 Singletary, The Mexican War, 166. 18 6 some interest in and appreciation of the wider implications of this unique event,” one which he saw as having a “profound influence upon the future course of American history.”21 Though his focus was on writing a summary accessible to the masses, Singletary does offer his own new interpretation of who is to blame for the war. Unlike the majority of earlier historians, Singletary does not point fingers at one side or the other, but instead holds both parties accountable. “The bad feelings that had slowly but surely grown out of the encroachments of one power and the brutalities of the other set the stage for war; political instability increased its probability; the failure of diplomacy made it inevitable.”22 Singletary’s summary ends simply and aptly with the sentence, “The war with Mexico was over,”23 offering little more analysis beyond his introductory comments. 10) In 1972, historian K. Jack Bauer gave a nod to Smith’s “classic,” as Bauer refers to it, but also justified why his current summary was necessary and appropriate. Admitting that few Mexican War sources have passed into the public domain without first passing the eyes of Smith, Bauer justifies his “trespass[ing] on Smith’s preserve” by citing the “truism that every generation must reinterpret history in the light of its own experience.”24 Bauer’s experiences, writing in the wake of the war in Vietnam, were indeed quite different from Smith who had the First World War as his reference point. With the contemporary conflict in Vietnam on his mind, Bauer makes many comparisons between the Vietnam War and the Mexican War. Highlighting the force of manifest destiny as the igniter of the conflict with Mexico, a conflict he views as unavoidable, 21 Singletary, The Mexican War, 4. Singletary, The Mexican War, 20. 23 Singletary, The Mexican War, 162. 24 Jack K. Bauer, The Mexican War: 1846-1848 (New York: MacMillan Publishing Co., Inc., 1974), xx. 22 7 Bauer states, “The story of the application of that force by James K. Polk, like that of America’s recent experience in Vietnam, depicts the dangers inherent in the application of graduated force. It is the story of an American administration which wished to live in peace with her neighbors but edged closer and closer to the abyss of war because it did not understand that the logic which it perceived so clearly was not equally evident in Mexico City.”25 Bauer also compares U.S. diplomacy surrounding the Mexican War’s conclusion with that of Vietnam. “As in Vietnam, much of the diplomatic story of the conflict swirls around the failure of the efforts of the American government to initiate negotiations to bring the war to a close.”26 Bauer’s main argument regarding the war, which makes no direct reference to Vietnam, is that the Mexican War was unavoidable. As he states, “The whole thrust of America’s physical and cultural growth carried her inexorably westward toward the setting sun and the Great Ocean.” 27 In other words, Bauer does not hold a nation responsible for the Mexican War, but simply the force of manifest destiny. 11) In the second half of the twentieth century, historians of the Mexican War, still writing with the aim of filling in the gap of scholarly work on this often neglected topic, have sought to do so, for the most part, in a way dramatically different from the historians discussed above. Instead of summarizing the war as a whole, many more modern historians have chosen to narrow their foci, looking closely at particular sub-topics within the Mexican War. 12) One sub-topic often analyzed is the politics and diplomacy of war. As earlier historians tried to make broad statements about the U.S. motivations for war, these later 25 Bauer, The Mexican War: 1846-1848, xix. Bauer, The Mexican War: 1846-1848, xx. 27 Bauer, The Mexican War: 1846-1848, xix. 26 8 histories aimed to take a closer look at the Polk administration to offer new interpretations of what motivated the political maneuvers of men in high office. In his book, The Monroe Doctrine and American Expansionism: 1843-1849, Frederick Merk argues that the Polk administration, fearful of Europeans taking over North American territory, initiating schemes to interfere with slavery within the U.S., and imposing monarchic forms of government on young struggling republics, called for a renewal of Monroe Doctrine policies to protect North America, but more importantly to protect United States interests there.28 Merk states, “In messages to Congress, in cabinet consultations, in instructions to diplomats abroad, and in discussions with political associates, the defensive theme of the Monroe message was extended so as to unite with the theme of advance.” 29 To prove his argument, Merk weaves a dialogue between the Polk administration and its opposition, as well as a “dialogue between European and American commentators on Polk’s ideas,” throughout his work to show to what extent the “Polk-Monroe doctrine” benefited from universal approval.30 13) Thomas Hietala’s Manifest Design: American Exceptionalism and Empire examines the motivations of the Polk administration as well, but makes a rather contradictory argument to that of Merk’s. Arguing not that it was “threats from abroad or demands from pioneers”31 that influenced U.S. foreign policy, Hietala argues instead that “foreign policy in the 1840s was primarily a response to internal concerns.”32 Interested in the Asian market, anxious about overproduction on domestic farms and plantations, 28 Frederick Merk, The Monroe Doctrine and American Expansionism: 1843-1849 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1966), ix. 29 Merk, The Monroe Doctrine and American Expansionism: 1843-1849, viii. 30 Merk, The Monroe Doctrine and American Expansionism: 1843-1849, xi. 31 Hietala, Manifest Design, xvii 32 Hietala, Manifest Design, xiii. 9 and aware that U.S. producers had to expand their trade,33 “Democrats (and Tyler Whigs) preferred new land and markets over extensive federal regulation and reform.”34 Hietala infers that “the news of the Mexican assault on American forces came as a great relief to Polk and his advisers, for it provided an opportune justification for a course they had already plotted.”35 When first published in 1985, Hietala’s argument was criticized by many who still followed the more nationalistic line of thought first promoted by Smith, which dispelled notions of U.S. greed and selfishness governing foreign policy. One particular critic said his book was really about the Vietnam War and not the Mexican. Aware that his line of argument irritated many, in the preface to Hietala’s revised edition, published in 2003, he includes a response to his opposition. As he states, his “perspective rankles because it is inconsistent with American exceptionalism – the belief that the nation’s politics and diplomacy have been uniquely altruistic, open, and therefore beyond reproach.”36 What Hietala represents is a historical shift away from the patriotic interpretations of the Mexican War argued by Smith and others, and a move toward a much more critical look at the motivations and actions of those involved in the war at every level. 14) Another sub-topic, or genre, of the historiography of the Mexican War is military history. Historians have looked at the military history of the Mexican War in many different ways. John Eisenhower, in an essay titled “Polk and His Generals”, chose to look at the war with a focus on the relationship between Polk and the generals who commanded troops in the war. What Eisenhower found was that the relationship between 33 Hietala, Manifest Design, 84. Hietala, Manifest Design, xiii. 35 Hietala, Manifest Design, 86. 36 Hietala, Manifest Design, xvii. 34 10 President Polk and his two principal generals, Winfield Scott and Zachary Taylor, were “unbelievably bad.”37 He argues, “this unhappy situation, the antagonism between Polk and his generals, affected the conduct of the war,”38 sometimes going so far as to cause “near disaster.”39 Placing the military leadership in the context of America’s experiences in other wars, Eisenhower refers to the clashes between these three men as unique in American history (note that he wrote and published this article in 1986). In attempting to explain how such conflicts and mis-management could have occurred between “three good men from the same region of the country,” Eisenhower points to the fact that “military professionalism, that attitude which separates the military from the mainstream of American Affairs, had not yet come of age,” as a leading factor.40 While Eisenhower maintains that military professionalism had not reached maturity during the Mexican War, many other historians argue that it was during the Mexican American War when military professionalism truly developed. As Singletary points out, “it was…the first of our [U.S.] wars in which a significant number of West Pointers played an important role.”41 For the first time, generals were able to truly surround themselves with “capable, competent, well-trained junior officers.”42 While Eisenhower may concede that West Pointers played a key role in the war, his conclusion is that the U.S. did not benefit from these trained soldiers, as the leadership from the top was so poorly managed. As Eisenhower concludes, “What all this boils down to, then, is that our principal antagonist in the Mexican War was ourselves….the U.S. was lucky.”43 Eisenhower, “Polk and His Generals,” 34. Eisenhower, “Polk and His Generals,” 35. 39 Eisenhower, “Polk and His Generals,” 63. 40 Eisenhower, “Polk and His Generals,” 63. 41 Singletary, The Mexican War, 3. 42 Singletary, The Mexican War, 3. 43 Eisenhower, “Polk and His Generals,” 35, 36. 37 38 11 15) While many other historians have chosen to look at the military history of the Mexican War through the traditional lens of leadership - looking at the Commander-inCheif and his generals - there has been a recent shift toward looking at the war through the eyes of the common soldier. Who were these men fighting in Mexico? What were their motivations to fight? How did they experience the war? James McCaffrey was one of the first to recognize the lack of scholarship on the common Mexican War soldier. As he writes in the preface to his Army of Manifest Destiny: The American Soldier in the Mexican War, 1846-1848, “there has been little attempt to address the day-to-day activities of all the American soldiers involved. The present study, then, attempts to fill this gap.”44 McCaffrey places the history of the Mexican War in the context of other U.S. wars as well, stating, “American soldiery during the Mexican War was not very different from the volunteer soldiers throughout American history.”45 Where McCaffrey does make a distinction between the Mexican War and other U.S. wars is in the Mexican War’s relative brevity and unparalleled number of victories. “This unbroken string of triumphs made the war much more palatable to both the American public and the soldiers” and “made it difficult for any sort of popular antiwar movement to get started.”46 This historian also marks the short successful war as a contributing factor to the way in which the U.S. troops maintained such low opinions of their enemy – the soldiers simply did not have any time or opportunity to gain respect for the military prowess and skills of the Mexicans.47 This theme of U.S. relationships with, and views 44 James A. McCaffrey, Army of Manifest Destiny: The American Soldier in the Mexican War, 1846-1848 (New York: New York University Press, 1992), xviii. 45 McCaffrey, Army of Manifest Destiny, 210. 46 McCaffrey, Army of Manifest Destiny, 206. 47 McCaffrey, Army of Manifest Destiny, 207. 12 of, the Mexican enemy will become an important sub-topic of its own, one to which several historians dedicate their entire work. 16) Crediting McCaffrey as filling a “notable void,” Richard Bruce Winders sees his own book, Mr. Polk’s Army: The American Military Experience in the Mexican War, as building on the historical movement which seeks to examine the daily life of the common soldiers involved in the war. Winders sees his book as being a part of the evolving category known as “ ‘new’ military history,” a genre of histories which seek, as Winder’s book seeks, to link “the army to the society that produced it.”48 17) Winders argues that the “American participants in the Mexican War shared a common experience.”49 The experience he is referring to is not simply the experience of fighting a war on foreign land, but the overall state-of-mind – the way these soldiers understood their experiences. Playing a key role in shaping these soldiers’ world views was nineteenth century U.S. society. As Winders argues, the soldiers “carried their cultural baggage with them” and “saw events through ‘Jacksonian’-colored glasses.”50 Winders expands his argument by making the claim that “many soldiers were concerned with serious political issues of the day.”51 Soldiers were proud of their political affiliations, making great displays of their political beliefs. As Winders came to understand the importance of politics and political affiliations to the soldiers, he expanded his argument to address the relationships between politicians and common soldiers, combining the social history of the common soldier with the more traditional Winders, Mr. Polk’s Army, xii. Winders, Mr. Polk’s Army, xi. 50 Winders, Mr. Polk’s Army, xii. 51 Winders, Mr. Polk’s Army, xii. 48 49 13 military history which examines those men in power who were making the strategic military and political maneuvers. Winders states: Democrats and Whigs alike struggled for control of the army, because each group realized that military victory on the battlefield was linked to political victory at the polls. The war and the effort to raise thousands of troops gave President James K. Polk and his party an excellent opportunity to reward loyal supporters with commissions and fill the officer corps with Democrats. Viewed in this way, “the army that fought the Mexican War was indeed ‘Mr. Polk’s Army’.”52 18) Paul Foos began writing his history, A Short, Offhand, Killing Affair: Soldiers and Social Conflict During the Mexican-American War, with the goal to form an understanding of “American society and thought in the 1840s.” Like McCaffrey and Winders before him, Foos chose the military, specifically the common soldier, as “the lens through which to view American society.”53 However, unlike the historians discussed above, Foos did not see all members of the army as sharing a common experience. Foos argues that it is “crucial to understand the two opposing poles of military organization and philosophy, the regular army and the volunteer militia.”54 Foos asserts in the introduction to his book that his history of the Mexican War “examines alternative perspectives.”55 For his research method, Foos purposely sought out “newly uncovered and long-ignored” sources on the topic. As he states, “as much as possible these sources offer[ed] commentary that eschews the heroic mode so common in Winders, Mr. Polk’s Army, xii. Paul Foos, A Short, Offhand, Killing Affair: Soldiers and Social Conflict During the Mexican-American War (Chapel Hill: the University of North Carolina Press, 2002), 9. 54 Foos, A Short, Offhand, Killing Affair, 9. 55 Foos, A Short, Offhand, Killing Affair, 4. 52 53 14 personal and public accounts of the 1840s.”56 Foos’s goal was to not simply add to the existing collection of Mexican War histories, but to enhance and, in many cases, call into question existing arguments regarding the war and the men who fought in it. 19) Contradicting McCaffrey’s argument that the relative shortness of the Mexican War coupled with the war’s consistent military victories helped maintain high soldier morale and prevent any strong opposition from forming, Foos dedicates a large portion of his book to describing the more brutal reality of war. As demonstrated by the dismal title he chose for his book and the topics of his chapters (Examples are “Discipline and Desertion in Mexico” and “Atrocity: the Wage of Manifest Destiny”), Foos paints a much darker picture of the average soldier’s life than the bright optimistic portrait painted by McCaffrey. 20) Contradicting Winders’s argument that the majority of soldiers viewed the war and the world through “ ‘Jacksonian’-colored glasses,” Foos argues that “the experiences of Americans as occupiers of Mexico shook the foundations of Jacksonian ideas and practices.”57 Foos pays particular attention to how the principle of herrenvolk democracy – a principle which, according to Foos “envisioned landed equality for whites, with servile subject races” - was reconsidered and assessed by these soldiers.58 As Foos sees it, the Mexican War “provided Americans with a venue to confront their own internal conflicts” as they fought a war widely promoted as a war fought in the name of white, Anglo-Saxon supremacy.59 While all soldiers confronted these issues, not all came to the same conclusions regarding race relations. As Foos summarizes, 56 Foos, A Short, Offhand, Killing Affair, 4. Foos, A Short, Offhand, Killing Affair, 5. 58 Foos, A Short, Offhand, Killing Affair, 5. 59 Foos, A Short, Offhand, Killing Affair, 5. 57 15 The naked opportunism of the 1846-1848 war, the class conflict that the army brought with it to Mexico, and face-to-face experience with the Mexican people would bring about changed racial thinking: some individuals and groups became more exploitive than ever, but others rejected the cant of racial destiny.60 21) As with other wars, historians are often inspired by specific battalions and many histories have been written examining closely individual U.S. Army regiments fighting in the Mexican War. Many of these much narrower military histories examine issues of identity and race as Foos did. For example, Robert Ryal Miller’s Shamrock and Sword: The Saint Patrick’s Battalion in the U.S.-Mexican War and Peter Stevens’s The Rogue’s March: John Riley and the St. Patrick’s Battalion take a close look at how this group of Irishmen experienced the war, while Sherman Fleek’s History May Be Searched in Vain: A Military History of the Mormon Battalion looks at the war from the perspective of some of its Mormon participants. 21) The Mexican War was both a conflict over a border and a war between two ethnically diverse and racially complex nations. Because of this, social themes - issues of identity, popular culture, and ideologies represented in and shaped by the conflict – are popular themes for historians to look at. Histories which focus on such issues are a relatively recent phenomenon in the historiography of the Mexican War, as they are in historiography in general. 22) One modern historian, Andre a complex and rarely discussed perspective to the historiography of the Mexican War in his Changing National Identities at the Frontier: Texas and New Mexico, 1800-1850. Understanding the 60 Foos, A Short, Offhand, Killing Affair, 5. 16 Mexican War as “unquestionably a war of conquest,”61 U.S. citizens living on the border between Mexico and Texas experienced the war. He argues that, “from the perspective of the frontier residents, it was a conquest mediated by Mexico’s pre-existing core-periphery tensions and a tangle of economic interests linking Mexico’s far north with the United States.”62 For these residents living on the border the Mexican War was not a one-time event that determined their fate but a “catalyst that rekindled longstanding national identity struggles” complicated by continuous “structural transformations.” For these frontiersmen the war was not a straightforward conflict that was distinctly right or wrong, but a war which “entailed both imposition and acquiescence, rivalry and complicity.”63 23) In his landmark work The Rise and Fall of the White Republic: Class Politics and Mass Culture in Nineteenth-Century America, historian Alexander Saxton examines the way in which white racism was shaped by and, in return, shaped U.S. politics and culture during this time. Saxton’s work has influenced many historians, including Mexican War historian, Shelley Streeby. Streeby’s book, American Sensations: Class, Empire, and the Production of Popular Culture, expands on Saxton’s work. While a discussion of national expansion and the expropriation of Western lands plays a key role in The Rise and Fall of the White Republic, Streeby was troubled that Saxton “had little to say about white U.S. America’s racial confrontations with Latinos or cultural production that focuses on Mexico and the Americas.”64 As she sees it, “class and racial formations and 61 Changing National Identities at the Frontier: Texas and New Mexico, 1800-1850 (Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 240. 62 Changing National Identities at the Frontier, 240. 63 Changing National Identities at the Frontier, 240. 64 Shelley Streeby, American Sensations: Class, Empire, and the Production of Popular Culture (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002), 15. 17 popular and mass culture in North-eastern U.S. cities are inextricable from scenes of empire-building in the U.S. West, Mexico, and the Americas.”65 Streeby’s book, therefore, was written to fill this void. She sees an examination of the Mexican War, a war she points out is often a “forgotten war,”66 as central to this purpose. She views the Mexican War, along with various other U.S. imperial schemes throughout the Americas, as having “crucially shaped U.S. politics and culture.”67 The dual meaning of the word American in the title of her book illustrates her complicated historical purpose. The use of the word American in American Sensations refers to both the “hemispheric dimensions” of the U.S. imperial activity and the “process whereby U.S. Americans appropriated the term ‘American’ for themselves.”68 23) The methodology which guided Streeby’s examination of the Mexican War and the way it shaped U.S. popular thought and ideologies was to use popular sensational literature from the time as her principal sources. Streeby found that “languages of labor and race were shaped in significant ways by inter-American contact and conflict”69 and that this evolving language was best represented in popular sensational literature. The word Sensation in American Sensations therefore refers to what she views as the “culture of sensation,”70 the prevalence of popular literature which exploited the American adventures in the Southwest and encounters with Latino culture. As Streeby discovered, her sources “both reveal[ed] and struggle[d] to conceal the role of U.S. imperialism in the Americas in the nineteenth century,” they both “bolstered and complicated” ways in 65 Streeby, American Sensations, 15. Streeby, American Sensations, xi. 67 Streeby, American Sensations, xi. 68 Streeby, American Sensations, 7. 69 Streeby, American Sensations, 15. 70 Streeby, American Sensations, 7. 66 18 which Americans came to understand themselves and their relation to their Latino neighbors.71 Many of the ideological ways of viewing whiteness and race formed during this time because of encounters between the white U.S. and Latino populations, Streeby argues, are still prevalent today, making an understanding of this period, and the Mexican War in particular, immensely significant to studies of race relations and culture within the U.S. 24) Streeby’s method of examining popular literature as a way to interpret broader issues and themes within U.S. society is one often used by historians. Because of the advent of the steam driven press, and the dramatic increase in printed and published works, popular culture was truly able to flourish during this period. There were literally hundreds of dime novels inspired by the war, and several historians have taken advantage of these works as valuable sources. One such historian is Robert W. Johannsen. 25) Johannsen approached the history of the Mexican War with one simple question, “What did the Mexican War mean to Americans in the mid-nineteenth century?”72 His historical goal was to decipher the “spirit” and “feeling” of the American people. As he uncovered this “spirit” and “feeling” he hoped to gain insight into how Americans’ perceptions of the war “revealed some of the characteristics of mid-nineteenth century American thought and culture.”73 While conducting research for his social history of the Mexican War, To The Halls of the Montezumas: The Mexican War in the American Imagination, Johannsen purposely avoided what he viewed as “conventional… political utterances of the time” because he viewed them as overused sources which, because of 71 Streeby, American Sensations, 7. Robert W. Johannsen, To The Halls of the Montezumas: The Mexican War in the American Imagination (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985), viii. 73 Johannsen, To The Halls of the Montezumas, vii. 72 19 their political nature, might easily cloud popular attitudes.74 Instead Johannsen used popular literature, music, drama, and art to form his interpretations. 26) To the Halls of the Montezumas in the way that it looks at U.S. society as a whole. Johannsen does not seek to discover the different ways Irish-working class immigrants, freed black men, women, and frontier residents viewed the war. Instead he seeks to discuss the perceptions of the war which relationships between the majority, or those with the majority of power, and minorities, Johannsen paints a broader portrait of American society, looking at the issues which were openly discussed and apparent on the surface and in mass culture. What Johannsen concludes in his study is that the “spirit” that shaped popular attitudes toward the war was generally optimistic, patriotic, and romantic. “For a time and for some people, the war with Mexico offered reassurance by lending new meaning to patriotism, providing a new arena for heroism, and reasserting anew the popular assumptions of America’s romantic era.”75 At the war’s conclusion, Johannsen argues that the U.S. perceived itself to be on the verge of a “new epoch in American history.”76 Americans were optimistic about a bright future for their nation, a nation Americans proudly viewed as a model nation. The “spirit” Johannsen claims Americans shared had no room for fears of civil unrest. Americans saw only progress and prosperity. Modern observers know better, for in little over a decade these U.S. citizens would find themselves involved in a bloody civil war. 27) Histories of the Mexican War have changed drastically over the years, varying both in the themes examined and the interpretations of how these themes played out in 74 Johannsen, To The Halls of the Montezumas, viii. Johannsen, To The Halls of the Montezumas, viii. 76 Johannsen, To The Halls of the Montezumas, 301. 75 20 the war. Many of the historians discussed here disagree with each other, and new contradicting interpretations are entering the field every year. As Foos reminds us, “Scholars of the Mexican-American War have been hard-pressed to remain objective in the face of the contentious politics of the 1840s, using them - intentionally or unintentionally – as a sounding board for the latter day political debates.”77 It was not simply the early historians, those who wore their bias proudly on their sleeve, who have allowed personal experiences and values to influence their interpretation of the war. PostVietnam interpretations of the Mexican War varied significantly from those written in the wake of World War I. Just as personal feelings on the morality of imperialism have shaped the way historians have portrayed the actions of the Polk administration, personal values have shaped the way people interpret who should be held responsible for the war, and consequently the differing ways in which people refer to the war. Was it the “Mexican War,” the “U.S. – Mexican War,” or the “North American Invasion of Mexico”? In the end, perhaps Hietala said it best when he wrote, “The events of the 1840s and their legacy remain controversial, and no author can satisfy avid partisans of any particular nation, party, leader, or people.”78 28) This paper began with an examination of the way in which the Mexican War has traditionally been a war neglected in the scholarly sphere. Historians today continue to express the need to fill gaps in the historiography of the Mexican War. Who knows when, if ever, the Mexican War will have as many scholarly works dedicated to it as those dedicated to more popular wars involving the United States of America. We can be 77 78 Foos, A Short, Offhand, Killing Affair, 9. Hietala, Manifest Design, xvii. 21 certain of one thing - historians will continue to research this war for generations to come, with each individual bringing something new to the field. 22 Works Cited Bancroft, Hubert H. “The War as an American Plot.” From The Mexican War: Was it Manifest Destiny? edited by Ramon Eduardo Ruiz. Hinsdale, Illinois: The Dryden Press, 1963. Bastert, Russell H. “Review of The Monroe Doctrine and American Expansionism, 18431849, by Frederick Merk.” The American Historical Review 73, no. 1 (October 1967), 231-232. Bauer, Jack K. The Mexican War: 1846-1848. New York: MacMillan Publishing Co., Inc., 1974. Eisenhower, John D. “Polk and His Generals.” From Essays on the Mexican War. edited by Douglas W. Richmond. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1986. Eubank, Damon. The Response of Kentucky to the Mexican War: 1846-1848. Lewiston, New York: E. Mellen Press, 2004. Fleek, Sherman L. History May be Searched in Vain: A Military History of the Mormon Battalion. Spokane, Washington: Arther H. Clark Co., 2006. Foos, Paul. A Short, Offhand, Killing Affair: Soldiers and Social Conflict During the Mexican-American War. Chapel Hill: the University of North Carolina Press, 2002. Hietala, Thomas R. Manifest Design: American Exceptionalism and Empire, revised edition. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1985. Johannsen, Robert W. To The Halls of the Montezumas: The Mexican War in the American Imagination. New York: Oxford University Press, 1985. Johnson, Walter. “The Mexican War.” History 1629 lecture. Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 15 Nov, 2006. McCaffrey, James M. Army of Manifest Destiny: The American Soldier in the Mexican War, 1846-1848. New York: New York University Press, 1992. Merk, Frederick. The Monroe Doctrine and American Expansionism: 1843-1849. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1966. Miller, Robert Ryal. Shamrock and Sword: The Saint Patrick’s Battalion in the U.S.Mexican War. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1989. 23 Muzzey, David S. “Review of The War With Mexico, by Justin H. Smith.” Political Science Quarterly 35, no. 4 (December 1920): 646-651. Priestley, Herbert Ingram. “Review of The War With Mexico, by Justin H. Smith.” The Hispanic American Historical Review 3, no. 3 (August 1920): 375-381. Changing National Identities at the Frontier: Texas and New Mexico, 1800-1850. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 2004. Salas, Elizabeth. “Review of American Sensations: Class, Empire, and the Production of Popular Culture, by Shelly Streeby.” The Pacific historical Review 72, no. 2 (May 2003): 296-297. Saxton, Alexander. The Rise and Fall of the White Republic: Class Politics and Mass Culture in the Nineteenth-Century America. with a foreword by David Roediger. New York: Verso, 2003. Singletary, Otis A. The Mexican War. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1960. Smith, Justin H. The War With Mexico, vol. I. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1919. Stevens, Peter F. The Rogue’s March: John Riley and the St. Patrick’s Battalion. Washington: Brassey’s, 1999. Streeby, Shelley. American Sensations: Class, Empire, and the Production of Popular Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002. Winders, Richard Bruce. Mr. Polk’s Army: The American Military Experience in the Mexican War. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1997. 24