Guiding Principles for Collaboration between Government and

advertisement

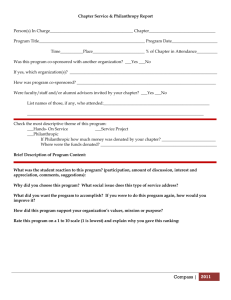

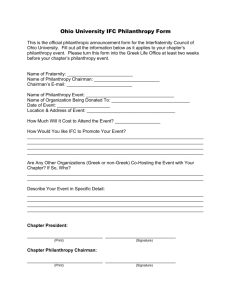

GUIDING PRINCIPLES FOR BUILDING COLLABORATIVE PARTNERSHIPS BETWEEN GOVERNMENT AND PHILANTHROPY Report and Case Studies March 2012 Philanthropy Consulting Service Marion Webster and Trudy Wyse PO Box 1011 Collingwood Victoria 3066 Australia ABN 57 967 620 066 T. +61 3 9412 0412 F. +61 3 9415 7429 E. consulting@communityfoundation.org.au W. www.communityfoundation.org.au 1. Background to the Project The Office for the Community Sector (OCS) within the Department of Planning and Community Development (DPCD) was established to support and build the capacity of community sector organisations so that they can be sustainable into the future. In 2009 the OCS set up the Philanthropy and Government Working Group to explore broad avenues for collaboration between philanthropy and government, with the aim of maximising the impact of government and philanthropic work and spending on the community sector. The Working Group has co-ordinated a series of events and briefings aimed at developing a mutual understanding of government processes, the philanthropic climate in Victoria and ways of engaging philanthropy in government work. In May 2011, a discussion paper entitled Guiding Principles for Building Collaborative Relationships between Philanthropy and Government was developed by the Working Group. The paper aims to highlight some common elements of successful collaborations between government and philanthropic grant makers. It outlines a set of draft principles which could guide a constructive collaborative approach between philanthropy and government grantmakers wanting to work together to support projects with community and not for profit organisations. The Australian Community Foundation’s Consulting Service was contracted to continue this work by assessing the value and relevance of the guiding principles against four selected initiatives being undertaken by not-for-profit (NFP) organisations and supported by government and philanthropy. The four case studies include: Strengthening Social Cohesion in Hume City - Supporting Parents Developing Children Project Loddon Mallee government and philanthropic partnership (Robinvale component) Children’s Protection Society – Early Years Education Research Program White Lion - Youth Mentoring Program Collaborative partnerships report March 2012 1 It became clear during the consultation phase of the contracted work that projects which are supported by both government and philanthropy sit on a continuum of engagement, as is outlined in greater detail in sections 3 and 4.1 of this report. The Working Group has agreed on a specific definition of a collaboration (see section 4.1, page 7) which does not necessarily apply to all of the four case studies. The discussion in this report, therefore, focuses on what constitutes a collaborative partnership, as opposed to much looser arrangements in which a project may be supported by philanthropy and government, but without a formalised relationship to guide the project’s development. The following sections of this report include a summary of local and international material of government philanthropy collaborative partnerships, general findings and observations on effective collaboration based on the documentation of the four case studies, recommendations re changes and additions to the draft guiding principles and an outline of each of the four case studies. 2. Project Methodology The Working Group nominated the 4 case studies to provide a variety of different types of arrangements and relationships that can exist between philanthropy, government and NFP organisations supporting a common project. At least one of the Working Group members was a partner in each of the case studies. A lead agency was identified for each case study and as part of this role, they provided background information and co-ordinated the involvement of the other partners in the project. The four lead agencies completed an initial questionnaire which provided information about the nature of the cross sectoral relationships and the extent to which the draft guiding principles were reflected in, and relevant to, the development and implementation of the partnership arrangements to date. This was followed by a group discussion with each of the case studies and involved some or all of the partner organisations. This discussion further explored the background to, and implementation of, the arrangement, from the different participants’ perspectives. Each of the draft principles was raised in the context of the project’s development, and the usefulness of the principles for guiding the development of effective collaborative partnerships was explored by the groups. Collaborative partnerships report March 2012 2 The information and analysis provided through the questionnaires and discussions formed the basis of the case studies and recommended changes and additions to the guiding principles. 3. Government Philanthropic Collaborative Partnerships - A Summary of Local and International material 'In the USA, Henry Ford once said, “Coming together is a beginning. Keeping together is progress. Working together is success.” The philanthropic sector’s relationship with the public sector is best described as mixed and uneven. While governments can hinder a foundation's mission, they also offer the potential to further the mission beyond what the foundation could accomplish by itself'. The Council on Foundations USA In the UK, this view has been echoed. 'For all the talk about public-private partnerships these days, the relationship between government and philanthropy remains awkward and incomplete. They are usually portrayed as opposites- two sides of a coin at best, adversaries at worst.' Macdonald and Szanto 2007 235-6 A scan of local and overseas material that looks at the role of government – philanthropic collaborations/partnerships tends to reflect the same “mixed and uneven” relationships. At the same time it is being increasingly recognised that the issues communities are currently facing are extremely complex, can be chronic and severe and spill over sectoral boundaries. The traditional silo approach where different sectors and agencies (government, philanthropy, corporations, community) respond in isolation and solely according to their own agendas and priorities is ineffective and limiting. There is a general acknowledgement in the literature that by leveraging the work of the government and philanthropic sectors, the reach of both philanthropy and government’s intellectual and financial capital and the scope of their successes can be broadened to achieve greater positive social change. The literature also recognises that good cross sectoral partnerships bring much more than financial resources, and can lead to a much better understanding and a redefining of the relationships and strategies, of both sectors which will hopefully lead to more sustainable change. Collaborative partnerships report March 2012 3 In both the USA and the UK considerable work has been undertaken to build and share knowledge about the opportunities and learnings about government – philanthropic partnerships. In the USA this has been done through the establishment of the Public – Philanthropic Partnership Initiative at the Council on Foundations. The program aims to: serve as the facilitator and go-to source for public-philanthropic partnerships; catalogue current opportunities and develop tools and resources to enable foundations to successfully partner with government; generate timely analysis and commentary to increase awareness and understanding among the foundation community and the government about all aspects of public philanthropic partnerships. It also provides a number of examples of successful partnerships. In the UK the Intelligent Funding Forum commissioned Dr Diana Leat to undertake a study: More than Money: The potential of cross sector relationships This comprehensive paper explores the varied ways funders from different sectors (government, business and philanthropy) are currently working together, how these relationships work in practice and the opportunities for clear collaboration in the future. The paper, while not listing a set of principles, does identify a number of “relationship ingredients” necessary to establish successful cross sectoral relationships. These include: - understanding what are the key drivers for the different sectors, as well as each other’s needs and constraints - respect and trust for each other’s skills and knowledge, and understanding how these can add value to each other’s work. It is also about acknowledging that it takes time and patience to build trust - shared vision and focus. This may not mean that all members to the relationship share exactly the same goals, but that they share at least one goal on which they are jointly focused for the purposes of the work being undertaken - clarity about boundaries, roles and structures, but with the acknowledgement that it is not always possible to know how things will develop - time commitment, which is dependent on the type of relationship. The associated time costs are then assessed on the benefits derived from the relationship. Collaborative partnerships report March 2012 4 A number of Victorian resources are available to assist organisations wishing to engage in cross sectoral partnerships. The Department of Planning and Community Development has produced a very comprehensive document Working in Partnership: Practical advice for running effective partnerships (Jeanette Pope 2008). This practical “how to” guide contains a number of detailed case studies and outlines five key factors for effective partnerships. These are: - a good broker/facilitator to build relationships - the right decision makers at the table with a commitment to contribute - a clear vision and objectives - good processes - ongoing motivation through evaluation and champions. Although not specifically focused on government – philanthropy partnerships, VicHealth has developed the Partnerships Analysis Tool, a resource for establishing, developing and maintaining partnerships for health promotion. The aim of this tool is to help organisations reflect on the partnerships they have established and monitor and maximise their effectiveness. Our Community has also developed a range of resource material on community- business partnerships. Both resources contain some good and relevant information. The Department of Human Services (DHS) has also had a long-standing and well developed approach to partnership and collaboration with the community sector. A formal partnership between the independent health, housing and community sector and the Department of Human Services has been in place since 2002 and is reviewed and re-signed every three years. A practical guide, the Collaboration and Consultation Protocol, was developed in 2004 to advance the way parties to the Partnership Agreement collaborate and consult in order to plan and deliver high quality services to the people of Victoria. The protocol is a guide and reference tool to promote partnerships through different stages of the process and outlines a shared approach to policy development processes, planning and service delivery. It also acknowledges the responsibilities and constraints faced by the Department and the sector when engaged in collaboration. Collaborative partnerships report March 2012 5 Building on the work of DHS, the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development (DEECD) has also written a framework for collaboration and consultation, titled DEECD – Victorian Community Sector Collaboration and Consultation Framework. This comprehensive publication resulted from the development of a DEECD – Victorian Council of Social Services Partnership Agreement 2010-2014, which itself came about in response to the recognition of the importance of partnerships between the Department and the diverse mix of community sector organisations with differing interests, mandates and governance structures. The development of the Framework also provides a platform for both the Department and community sector to include collaboration and consultation within strategic planning and corporate strategies, which will build on existing practice. The publication contains information on what it is that constitutes effective collaborations and consultations and covers the benefits, challenges and enablers. It also provides information on some practical steps and mechanisms that could be helpful in establishing them. What is common to all the material referred to here is the recognition that a cross sectoral partnership can take many forms and that each relationship sits somewhere on a continuum in terms of the level and degree of engagement. They may range from a loose networking arrangement through to a highly structured collaboration. These are described differently, but can be categorised broadly as follows: Networking involves the exchange of information for mutual benefit. This requires little time and trust between partners and will most likely involve talking, sharing knowledge and learning. Coordinating involves exchanging information and altering activities of each organisation for a common purpose. This may involve developing a coordinated campaign to lobby for better services Cooperating involves exchanging information, altering activities for a common purpose and sharing resources. It requires a significant amount of time, a level of trust between partners, and an ability for agencies to share turf. This often involves independent co-funding by each organisation, rather than contributing to a common pool. Collaborative partnerships report March 2012 6 Collaborating includes enhancing the capacity of the other partners for mutual benefit and a common purpose. Collaborating requires the partners to give up a part of their turf to another agency to create a better or more seamless service system. This will involve high levels of trust, and will include complementary resourcing, collaboration in all aspects of planning, governance, implementation and evaluation. In addition, from his experience of working with the Helen Macpherson Smith Trust and ANZ Trustees, Chris Wootton, a member of the Working Group, has developed a visual representation of the possible Models of Engagement between government, philanthropy and the not-for-profit sector. This is outlined in Appendix 1. Links to the international and local material referred to in this section can be found at Appendix 2. 4. General comments and learnings from the Collaboration Project 4.1 The nature of collaborations As identified in the scan of international and local material, cross sectoral partnerships between government, philanthropic and not for profit organisations can take many forms, and each sits somewhere on a continuum in terms of the level and degree of engagement. At one end there can be a loose networking arrangement, at the other a fully developed collaboration, which is a far more formalised and structured arrangement. During the research phase of this project it became clear that the four case studies sit along this continuum, and are not all collaborations. Following discussion of the issues raised by the analysis of the case studies, the Working Group agreed on the following definition of a collaboration: A cross sector collaboration is a deliberate, structured arrangement which brings together each sector’s intellectual, organisational and financial capital to meet agreed goals. It involves joint planning, resourcing, governing and monitoring. Collaborative partnerships report March 2012 7 Based on this definition, the Children’s Protection Society (CPS) and Whitelion projects do not fit into the category of collaboration. While both projects do involve government, philanthropy and the NFP organisation, there is no structured arrangement between government and philanthropy, rather the government and philanthropic partners have their own discrete relationships with the NFP organisation. Both projects were initiated by their organisations in response to a need they had identified in the areas in which they operate and the potential funding partners were then sought. In the case of CPS, following several years of in depth research, the organisation developed a project to provide early learning interventions for at risk children and their families. With a clear project plan in place and with clarity about the mission, vision, roles and priorities of the project, CPS engaged their funding partners. While all funders have worked closely with CPS and have developed trust, the relationship has been one that has involved independent co-funding rather than a collaboration which, from the inception of an idea, brought CPS, philanthropic funders and government together to jointly address an identified issue. Similarly, in the case of Whitelion, the Mentoring Program already existed prior to the involvement of all the funding partners. The program has functioned through different funding stakeholders providing support to specific elements of a broader Mentoring Program, all of which have a preventive focus in common. The Portland House Foundation and the Medibank Community Foundation provided support for mentoring of young people currently living in custody at one of Melbourne's youth justice facilities. The Department of Human Services supports the mentoring program which works with young people preparing to leave out of home care. While the relationship between Portland House and Whitelion has been an excellent co-operative arrangement, with high levels of trust and regular contact, along with a commitment to long term funding, the overall Mentoring Program has no t been a structured collaboration with all parties coming together at the outset for a mutually agreed purpose. Rather relationships have been independently built between Whitelion and their various funders. Collaborative partnerships report March 2012 8 The other two initiatives, the Loddon Mallee partnership and the City of Hume Supporting Parents Developing Children initiative sit clearly in the collaboration category. In both these cases, the projects were initiated by a group of people from the philanthropic , government and community sectors coming together with the shared purpose of addressing an identified community issue. A great deal of time was taken in both cases with all parties working together with the community to build trusting relationships, agree purposes and desired outcomes, as well as identify and scope the specific projects that were eventually agreed upon and supported by a number of philanthropic and government funders. The feedback provided in the rest of this section by the four groups of case study participants on the draft guiding principles, relates to the principles’ relevance and usefulness to the establishment and operation of collaborations, based on the more formal definition agreed to by the Working Group. Collaborative partnerships report March 2012 9 4.2 Memorandum of Understanding All four case studies agreed that a Memorandum of Understanding was not an appropriate term to be used in the guiding principles, as it had a specific legal meaning, particularly for the Federal government. All felt however, that it was important that there is a clear and agreed understanding of the mission and purposes, as well as the roles and responsibilities of all partners, at an early stage of a collaboration, even though it was recognised that there was a need to have the flexibility to accommodate change as the collaboration evolved. ‘Statement of Intent’ was the preferred term for the document in which this would be spelt out. 4.3 Dedicated staff member It was generally agreed that a complex collaboration across philanthropy, government and the community sectors needed a person with the dedicated responsibility to co-ordinate governance arrangements, manage communication between partners, oversight project development and implementation and complete reporting and accountability requirements. In some cases a collaboration manager would be appointed specifically to work for the collaboration, in others an existing staff person from one of the partner organisations would take on this role as a key part of their work. 4.4 Reporting requirements In three of the case studies the issue of the administrative burden imposed by the number and range of reporting requirements for the funding partners in a collaboration, particularly those required by federal government departments was raised. The streamlining of accountability requirements was seen to be an important issue for the smooth running of collaborations. As discussed in 4.3, it was agreed that it was important to have a dedicated staff person in order to successfully manage these demands and the myriad governance, operational and co-ordination aspects of a complex collaboration. 4.5 Ensuring an easy transition for new partners in the collaboration As most collaborations span a number of years there will be inevitably be staff changes in the partner organisations. The importance of documenting the process and the history and culture of the collaboration was stressed. This, together with having a dedicated staff person responsible for the management of the project, was seen as important factors in ensuring a smooth transition and comprehensive induction for new staff and/or funders joining the collaboration. Collaborative partnerships report March 2012 10 4.6 Engaging all levels of staff from the organisations involved with the collaboration. For three of the case studies the importance of engaging and involving relevant personnel at all levels of the partner organisations including organisational heads, senior decision makers, program and operational staff. Maintaining their involvement meant that they remained abreast of any changes that may occur in the projects over time, were more likely to contribute their expertise and were able to be champions for the projects. 4.7 The importance of clear and regular communication All of the case studies stressed the importance of regular and clear communication, particularly when and if problems arose. It was agreed that this involved establishing clear communication protocols early in the project and ensuring that these included both senior, as well as operational, staff. 4.8 Support for the principles There was overall support for the development of a set of principles to guide collaborative arrangements. Most of those who participated in the group discussions indicated that there were guiding principles that underpinned their work together. However, for many these had never been explicitly stated. Feedback suggested that the draft guiding principles were too succinct and needed to be expanded to provide more context and meaning. It was felt that each principle needed to make sense as a standalone statement and that the addition of a preamble would assist in providing further context. Collaborative partnerships report March 2012 11 Guiding Principles for Successful Collaboration – Recommended changes 5. Preamble: This would cover the following points: - The relationship between funders and NFP organisations can take many forms and sit on a continuum – from juggling a range of funders to a completely cohesive, well harmonised collaboration. A cross sector collaboration is one in which there is a deliberate, structured arrangement which brings together each sector’s intellectual, organisational and financial capital to meet agreed goals. It involves joint planning, resourcing, governing and monitoring. - The fundamental basis for any collaboration is clarity regarding the assumptions of each partner about where they’re coming from, so that any differences are resolved at the outset. - Collaborations are only useful if they produce better outcomes for the community. 1. Creating the Environment 1.1 Engage each other early when the potential idea/interest/need for a collaborative approach is being considered 1.2 Ensure that expectations about goals and how partners are going to work together are clarified early on in the collaboration’s development 1.3 Recognise that collaboration works most effectively when the partners have shared values and principles, and when it meets each organisation’s guidelines and agendas. 1.4 Government/philanthropic collaborations work better when each sector understands the others directions and priorities and philanthropy understands government’s policy environment. 2. Shaping Partnerships and Building Relationships 2.1 Understand each other’s roles, policies, priorities and limitations 2.2 Ensure sufficient time to develop trust, mutual respect and agreed approaches 2.3 Ensure the right people are at the table(s), with commitment and involvement from senior and operational representatives of each partner organisation, as appropriate. Seek consistency of personnel representing the partners over the length of the collaboration, as far as possible. Collaborative partnerships report March 2012 12 2.4 Develop a formalised ‘Statement of intent’, once principles, goals, outcomes, expectations, roles and responsibilities are agreed. 2.5 Build in a flexible approach to roles and responsibilities and collaboration activities in order to accommodate changing circumstances and opportunities as they arise. 2.6 Appoint a member of the collaboration to drive and co-ordinate governance, operational and communication activities and build this role into their job description for the duration of the collaboration (this role would generally be taken by the lead agency). 3. Decision Making and Management Practices 3.1 Agree to processes for selecting organisations to be funded and the nature of projects to be jointly supported 3.2 Communicate frankly throughout the collaboration time frame 3.3 Document the history, context and development of the collaboration. Where there is a change of personnel, ensure that a formal handover process is put in place to ensure adequate information about the history and culture of the collaboration is passed on. 4. Evaluation and Sustainability 4.1 Ensure there is an evaluation framework and the resources available to undertake the level of evaluation agreed upon. 4.2 Address sustainability issues early, including development of a funding plan, where appropriate. As part of this, plan and develop an exit strategy if the collaboration, or partners’ involvement in it, is time limited. Collaborative partnerships report March 2012 13 6. Case Studies The following case studies have been developed using the information provided in the questionnaires and from the discussion at the group sessions. There are 3 sections to each case study: Identifying information Background and impetus for the establishment of the collaboration/project Assessment of the collaboration/project against each draft guiding principle Summarised below are key features of each of the case studies, reflecting the nature and strength of the partnerships. In writing up the individual case studies, the term ‘collaboration’ has been widely used, as this was the term originally used in the questionnaire and group discussions and is the context in which the responses and feedback were provided. Collaborative partnerships report March 2012 14 6.1 Summary of the key features of each case study Supporting Parents Developing Children - Hume Project Initiation by a philanthropic organisation, based on research and commitment/leverage to bring other partners on board. A key goal was to build a collaborative approach, bringing philanthropy, government and the NFP sector together for a shared outcome. Recognition of the need for coordination of the collaboration and the opportunity to build upon already established community relationships. Creation of a dedicated staff position to make this happen. Resourcing of collaboration evaluation which can identify and address problems, as well as provide learnings for the future. Loddon Mallee government and philanthropic partnership Foundation led coming together of government and philanthropic partners around a difficult, intractable problem and commitment to work with the community and community organisations over the long-term. Recognition of the fundamental need to build trust in a wary and conflicted community. Strength of, and commitment to, the funding partnership which facilitated the allocation of government funding for work in communities that fell outside of the guidelines for established program funding pots. Children’s' Protection Society – Early Years Education Research Program Clarity of vision and evidence base built by lead agency, enhancing capacity to bring others on board. Identification of partners’ roles in addition to funding, as fundamental to project success (leverage with others, advocacy, influence etc). White Lion - Youth Mentoring Program Strong individual partnerships with funding bodies. Recognition of the potential for building a more formalised and structured joint collaboration, which could strengthen relationships and ensure greater use of partners’ skills and expertise for benefit of the Program. Collaborative partnerships report March 2012 15 Appendix 1 Four M Models of Government/Philanthropy/NFP Engagement The following is a visual representation of possible models of engagement between government, philanthropy and not-for-profit organisations. It was prepared by Chris Wootton, based on his experience working for the Helen McPherson Smith Trust and ANZ Trustees. It demonstrates that cross sectoral relationships can take many forms. • Model 1 Government is the lead and engages with the NFP sector – who then may or may not seek philanthropic support eg State Government Community Building Initiative 20052010 (which then brought in Helen Macpherson Smith Trust). • Model 2 The NFP sector is the lead (and may or may not engage with philanthropy) and then seeks government involvement eg CPS and Whitelion Case Studies • Model 3 Government and Philanthropy engage (with Government or Philanthropy taking the lead role in the relationship) and then secure involvement of NFP sector eg Hume case study, Aust Community Foundation’s MacroMelbourne Initiative, Government/Helen Macpherson Smith Trust Youth Mentoring 2007-2011 • Model 4 All parties work together to explore solution(s) to a complex issue and/or where Philanthropy can play a facilitation or independent broker role eg Loddon Mallee Case Study Collaborative partnerships report March 2012 16 Appendix 2 List of International and Local References Public – Philanthropic Partnership Initiative: Council on Foundations. Can be found at: http://ppp.cof.org The Intelligent Funding Forum, More than Money: The potential of cross sector relationships by Dr Diana Leat. Can be found at: www.acf.org.uk/iff/ Macdonald and Szanto: Private Government Philanthropy: Friend or Foes? Article in Mapping the New World of American Philanthropy by Raymond and Martin. Published by John Wiley & Sons 2007 Working in Partnership: Practical advice for running effective partnerships by Jeanette Pope, 2008. The Department of Planning and Community Development: Can be found at: www.dpcd.vic.gov.au Partnership in Practice: Collaboration and Consultation protocol The Department of Human Services. Can be found at: www.dhs.vic.gov.au DEECD – Victorian Community Sector Collaboration and Consultation Framework. The Department of Education and Early Childhood Development(DEECD). Can be found at: www.education.vic.gov.au The Partnerships Analysis Tool: A resource for establishing, developing and maintaining partnerships for health promotion. VicHealth. Can be found at: www.vichealth.vic.gov.au Our Community has developed a range of resource material on community- business partnerships. Can be found at: www.ourcommunity.com.au Collaborative partnerships report March 2012 17