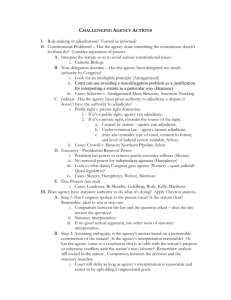

statutory construction* for general use by

advertisement