Sources of Friction in Greek

advertisement

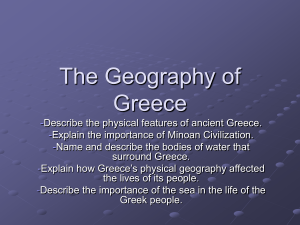

Sources of Friction in Greek-Turkish Relations: the Aegean Dispute Olga Borou, University of Athens and Egemen Ozalp, Sabanci University 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 3 Chapter One CONFRONTATION IN THE AEGEAN ................................................................................. 6 1.Delimitation of the Continental Shelf ........................................................................................... 6 The Internationalization of the dispute .......................................................................................................... 6 The Greek and Turkish arguments ................................................................................................................ 7 2. Territorial Waters and National Airspace ................................................................................ 10 a. The extension of the Greek Territorial Sea: Right or Abuse? ................................................ 10 The view from Ankara:................................................................................................................................ 10 The view from Athens ................................................................................................................................. 12 b. The National Airspace ................................................................................................................ 14 3. The Athens Flight Information Region (FIR Athens) ............................................................. 14 4. The Military Status of the Islands of the Eastern Aegean Sea ................................................ 16 Chapter Two NATO AND THE GREEK-TURKISH CONFLICT .............................................................. 17 Chapter Three ATTEMPTS FOR RESOLUTION ......................................................................................... 20 Conclusions ............................................................................................................................. 25 REFERENCES ....................................................................................................................... 26 2 Introduction Conflicts are the reflections of on-going dissatisfactions in everyday life and exist in all parts of the world. But they comprise solutions in human nature itself. Solutions require complex analysis and improvement of diplomacy and conflict resolution techniques based on systematic research. The Greek-Turkish conflict evolved into a network of mutual problems since the beginning of the 20th century, which has deep social and historical roots demanding long-term political incentives. The Aegean dispute in this crux is the crystallization of the conflict on a geographical crossroad of security and energy matters of Turkey and Greece, with their statuses in the international bodies to which they are parties. The sources of frictions in the Aegean Sea operate in a way that they provide each other the reproducible political capital for sustainable suffering. The network of relations is already there, like a functioning mechanism but its fuel is a mixture of xenophobia, suspicion and historical memories of both sides full of hatred and dissatisfaction. Turks and Greeks are inevitably realist in terms of International Relations theory; but the other side of this rusty coin is that both societies are not alien to each other’s worlds; they have a history of relationship, even negative. Thus, it is possible and easier to transform friction into co-operation than confidence-building between any other societies that do not know each other’s reflexes, by providing flow of information between the two societies; because the fundamental need of Greeks and Turks is first of all to hear each other, which can pave the way to new openings in economic and political relations. Lack of circulation of information between the two societies, their national memories, fear for each other and suspicion have high costs for both parties of the conflict such as high defense expenditures, impact of security dilemma on policy makings and loss of possible opportunities of being co-operating partners in the Aegean and the Balkans. Greeks and Turks do not approach to learn each other’s culture although theirs are two of the most valuable and historical ones; so in a chain-reaction of rapprochement, the first step remains missing. In fact, this lose-lose situation should hasten the transformation of sources of frictions into dynamics of co-operation for the sake of the two countries . It is vital for both parties to sustain political will for transformation of conflicts into common interests that requires time to build-up trust step by step between Greece and Turkey. “Neither Rome nor any empire survived forever”1; so any state today or in future also will not. Turkey and Greece should use their social, economic, political and natural 1 Clinton, Bill. Conference at Çırağan Palace, Istanbul: July 9th, 2002. 3 resources efficiently for their citizens’ wellbeing rather than spending their powers on continuous artificial tensions and various possibilities of confrontation. The Aegean dispute is deaf and blind in nature as Greece and Turkey have been keeping different definitions for the same dissatisfaction, which they do not want to give up and at the same moment without hearing each other’s intentions. Although Cyprus is stressed more as the main source of friction between Greece and Turkey, especially after the military confrontation in 1974, the Aegean dispute is not less important. They all require harmonization of two States’ perceptions through time by diplomatic maneuvers and further steps for co-operation on economy and education in order to support their foreign policy incentives. Both Turkey and Greece should release their next generations from historical standings based on fear and from their Achilles’ heel of inside politics as well. In March 1987 the long-running problem over the location of the continental shelf and by extension rights to exploit potential oil reserves under the sea bed had led to a crisis and brought the Davos Agreement to end the crisis. Although both governments agreed in principle to pursue a series of confidence-building measures, they designed to reduce immediate tensions in the Aegean and to provide a conflict resolution process, but these efforts remained largely unconsummated. Relations were further strained by the end of 1995 after the Greek parliament ratified the United Nation’s Law of Sea (LOS) Treaty2. Turkey has not recognized the LOS Treaty, stressing that its implementation would turn 70 per cent of the Aegean into Greek sovereign territory and unacceptably restrict freedom of navigation3. Turkey and Greece again came back to the brink of an armed conflict on 28 January 1996, as a result of a crisis regarding the status of the Kardak / Imia Rocks4. After the crisis, diplomatic efforts to reduce tension in the Aegean gained a new momentum and after months of negotiations, on 4 June 1998, Turkey and Greece agreed to a limited set of confidence-building measures (CBMs) proposed by the NATO Secretary-General Javier Solana. Both the Memorandum of Understanding signed in Athens on 27 May 1998, and the Guidelines for the Prevention of Accidents and Incidents on the High Seas and International Airspaces signed in Istanbul on September 1988, oblige the two countries to respect each 2 http://www.un.org/Depts/los/convention_agreements/convention_overview_convention.htm Aydan, S. Gülmen. “Negotiations and Deterrence in Asymmetrical Power Situations: The Turkish-Greek Case”. Turkish-Greek Relations: The Security Dilemma in the Aegean. Aydın, Mustafa & Ifantis, Kostas. (Ed.) London and New York: Routledge, 2004. 213-244. 4 Kriesberg, Louis. Program on the Analysis and Resolution of Conflicts, 1990-1991 Annual Report. Syracuse: Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs, Syracuse University, 1991. 3 4 other’s sovereignty and territorial integrity and recognize their rights to use high seas and international airspace of the Aegean. They have also agreed to allow NATO a role in monitoring air sorties over the Aegean. However, similar to the previous attempts, although both sides agreed to implement these declarations, they were not complied with.5 The Aegean conflict is a set of four separate issues, which include: (i) the breadth of territorial waters; (ii) delimitation of the continental shelf; (iii) militarization of the Eastern Aegean islands and (iv) airspace related problems. This paper attempts to provide a comprehensive picture of the Aegean dispute, describe the positions of the two parties and propose some ways of resolution. 5 Aydan, S. Gülmen. “Negotiations and Deterrence in Asymmetrical Power Situations: The Turkish-Greek Case”. Turkish-Greek Relations: The Security Dilemma in the Aegean. Aydın, Mustafa & Ifantis, Kostas. (Ed.) London and New York: Routledge, 2004. 213-244. 5 Chapter One CONFRONTATION IN THE AEGEAN 1.Delimitation of the Continental Shelf The Continental Shelf dispute is related to the exploitation and exploration of the resources under the seabed and subsoil of the submarine area beyond the territorial sea, to the point where the land mass is deemed to end. The continental shelf (CS) dispute stems from the absence of a delimitation agreement effected between the two countries and it has a bearing on the overall equilibrium of rights and interests in the Aegean, as it concerns areas to be attributed to Turkey and Greece beyond the 6 mile territorial sea. The Internationalization of the dispute The CS issue has in the past led to tensions between Turkey and Greece. Following scientific research activities undertaken by Turkey in 1976, Greece has made recourse to both the United Nations Security Council and the International Court of Justice (ICJ). On August 10, 1976, Greece addressed a communication to the President of the Security Council requesting an urgent meeting of the Council on the ground that "following recent repeated flagrant violations by Turkey of the sovereign rights of Greece in the continental shelf in the Aegean, a dangerous situation has been created threatening international peace and security." On the same day, by unilateral application, Greece instituted proceedings in the ICJ against Turkey in "a dispute concerning the delimitation of the continental shelf appertaining to Greece and Turkey in the Aegean Sea, and concerning the respective legal rights of those States to explore and exploit the CS of the Aegean." Greece’s application had two parts. First, Greece requested for interim measures of protection by virtue of Article 41 of the Statute of the ICJ.6The Court refused the Greek request for interim protection because it did not find enough evidence of “irreparable 6 Article 41 (1) of the ICJ Statute states that “the Court shall have the power to indicated, if it considers that circumstances so require, any provisional measure which ought to be taken to preserve the respective rights of either party.” 6 prejudice” to Greece’s rights.7 Second, Greece asked the Court to review the merits of the Shelf dispute and determine each party’s share of the continental shelf in accordance with international law. Before delving into the merits of the dispute, the Court had to decide whether it had jurisdiction over the case since there was no compromis of joint application. Greece argued that both the both the Brussels Communique and the 1928 General Act for the Pacific Settlement of International Disputes evidenced Turkish consent to jurisdiction. However, the Court rejected both grounds of alleged Turkish consent. It found that the Brussels Communique did not constitute a binding acceptance of jurisdiction in cases involving Greece’s territorial status. Finding the reservation applicable to maritime delimitation cases, the Court concluded that it lacked jurisdiction to entertain the shelf dispute. Grecce’s efforts to internationalize the dispute and find a legal settlement had, therefore failed. But in terms of the actual substance of the dispute, no grounds had been lost or gained. For the time being, Turkey and Greece had no other choice than to seek a solution through negotioations8. In conformity with the Security Council decision, and in view of the Court's rejection of the Greek contention and claims, Turkey and Greece signed an agreement in Bern on 11 November 1976. Under this Agreement, the parties decided to hold negotiations with a view to reaching an agreement on the delimitation of the continental shelf. They also undertook to refrain from any initiative or act concerning the Aegean continental shelf. 1976 Bern Agreement is still valid and its terms continue to be binding for both countries9. The Greek and Turkish arguments Greece claims that the Aegean shelf dispute is legal and involves the interpretation of conventional and customary law applicable to maritime delimitation10. As a result, the best forum for resolution is the ICJ whose duty is the application of the rules and norms of international law. On the contrary, Turkey favors a diplomatic settlement and contents that the shelf dispute is of high political nature and challenges Greco-Turkish territorial 7 Aegean Sea Continental Shelf Case, Request for the Indication of Interim Measures of Protection, 1976, para.29 8 Jon M. Van Dyke, “ The Role of the Islands in Delimiting Maritime Zones; The Boundary Between Turkey and Greece” in Dis Politika, Foreign Policy Institute, Ankara, Volume XIV, Nos.3-4,p.64 9Ibid. 10 According to Article 36(2) of the Statute of the International Court of Justice, legal disputes are the conflicts that concern the interpretation of a treaty, a question of the international law, a breach of an international obligation, or the nature and extent of reparation. Legal conflicts are resolved by adjudication and “should as a general rule be referred by the parties to the International Court of Justice.” Charter of the United Nations, Article 36(3). 7 and political relations11. The Turkish perception regarding the Aegean can be summarized on the following lines: a. The Aegean is a common sea between Turkey and Greece. b. Both countries should respect each others legitimate rights and vital interests. c. These freedoms at the high seas and the air space above it, which at present both coastal states as well as third countries enjoy, should not be impaired. d. Any acquisition of new maritime areas should be based on mutual consent and should be fair and equitable12. The shelf dispute is both legal and political. It has an extensive foundation in international law, for Maritime law provides a clear definition of states shelf rights and describes methods for delimiting the continental shelf between opposite and adjacent states. What is more, the numerous shelf delimitation cases brought to the ICJ and to Arbitration Tribunals in the past further testify for the legality of continental shelf disputes. However, one has to bear in mind that most of the times a dispute is not devoid of political, economic and social considerations13 .As R.Higgins emphasizes, “there is no avoiding the essential relationship between law and policy”.14Although the Aegean shelf dispute is both political and legal, Greece and Turkey treat these two characteristics as if they were mutually exclusive. The reason for this is that political and legal disputes point to different forums for resolution, and each forum serves the two parties differently. According to the Greek Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the delimitation of the continental shelf of the Aegean Sea is, from the point of view of international law, the only existing real issue between Greece and Turkey15. The legal principles presented by Greece are deeply grounded in conventional law and specifically in the 1958 Geneva 11 Political disputes involve the modification of the status quo rather than the interpretation of law. They are resolved by diplomatic negotiation, and, according to Article 35 of the UN Charter, they can be referred to the UN Security Council and General Assembly. 12http://www.mfa.gov.tr/MFA/ForeignPolicy/Regions/EuropeanCountries/EUCountries/Greece/GreeceLinks/T he_Delimitation_of_the_Aegean_Continental_Shelf.htm 13 In 1978 the ICJ asserted that “a dispute involving two states in respect of the delimitation of their continental shelf can hardly fail to have some political element.” ICJ Reports, Aegean Sea Continental Shelf Case, 1978, para.31 14R. Higgins, Problems and Process:International Law and How We Use It, New York, Oxford university Press Inc., 1994, p.5 8 Convention on the Continental shelf. Tree Articles of the Geneva Convention deserve particular attention. Article 1 provides the definition of the continental shelf and states that islands possess their own shelf. Article 2 outlines the nature of the coastal states rights on the continental shelf. A state is said to have sovereign and exclusive rights to explore and exploit the continental shelf. Article 6 outlines the principles for delimiting the continental shelf between neighboring states.16 Athens argues that the boundary of the Aegean shelf should be the median line between the eastern Greek islands and the Anatolian coast. Equidistance should not be applied between the Greek and Turkish continental coasts because firstly, this delimitation ignores islands entitlement to a continental shelf and secondly, it disrupts the “political continuum” that exists between the Greek islands and the Greek mainland. According to Andrew Wilson, “Greece’s position contains no threat to Turkey, since her claim to the continental shelf carries no claim to the superadjacent waters, in which Turkish and international shipping pay move freely.”17 Thus Greece argues that the delimitation of the Aegean Sea Continental Shelf must be effectuated on the basis of the existing geological facts and the applicable rules of international law, and not by the application of the principle of equity as proposed by Turkey. Greece contends that all of its islands in the Aegean, as an integral part of Greece’s territory and sovereign rights, are entitled to their full continental shelf rights under international law and under the 1982 UN convention on the law of the sea (art. 121). According to this article only the "rocks which cannot sustain human habitation or economic life of their own shall have no exclusive economic zone or continental shelf" (art. 121 para. 3)18. Moreover Greece argues that, its sovereign rights, as a coastal state, over its Aegean Continental Shelf are inherent and exist ipso facto and ab initio, without requiring any legal or other act of recognition. Additionally, Greece argues that the existing geological structure of the Aegean Sea, as supported by seismotectonic, volcanological, platetectonic and mineralogical evidence, clearly shows that its Aegean Sea Continental Shelf constitutes a natural prolongation of its landmass. 16 David Ott, Public and International Law in the Modern World, London: Pitman Publishing, 1978, p.219 A. Wilson, “The Aegean Dispute”, in Jonathan Alford, ed. Greece and Turkey: Adversity in Alliance, New York, St. Martin’s Press, 1984, p.92. 18It is true that Turkey has not ratified any of the aforementioned conventions. However, it should be stressed that the ICJ has explicitly accepted (1969, case of the north sea continental shelf) that article 1 of the 1958 Geneva convention on the continental shelf should be regarded as crystallizing rules of customary International Law, thus accepting that the islands have a continental shelf on the same footing as land territory. www.mfa.gr 17 9 2. Territorial Waters and National Airspace a. The extension of the Greek Territorial Sea: Right or Abuse? The view from Ankara: The Aegean is a semi-enclosed Sea located in between the Turkish and Greek mainlands and is dotted by thousands of islands, islets and rocks. Both Turkey and Greece presently exercise a 6 nautical miles breadth of territorial waters in the Aegean which enables almost half of this Sea and the airspace above it, being freely used as high seas and international airspace by Turkey and Greece as well as third countries. Under the present 6 mile breadth of territorial waters, about half of the Aegean is high seas. The extension by Greece of her territorial waters beyond the present 6 miles in the Aegean, will have most inequitable implications and would constitute an abuse of right for the following reasons: a) Such an action will turn the Aegean into a Greek Sea to the detriment of Turkey's vital and legitimate interests. In case of an extension, in practical terms Turkey will be locked out of the Aegean and confined to its own territorial waters. Following an extension, neither Turkey nor any other state will be able to benefit from a diminished proportion of high seas in the Aegean for economic, military, navigation and other purposes. b) Turkey's access to the high seas will be blocked and its Aegean coast will be encircled by Greek territorial waters: Should the territorial sea be increased for instance to 12 miles Turkey's 2820 km long coastline to the high seas will be encircled by Greek territorial waters. Turkey's access from its west shores to the international waters of the Aegean and similarly from the Aegean to the Mediterranean will almost be curtailed. c) Turkey's military, economic and scientific interests will be seriously jeopardized:As a result of the constriction of the high seas, Turkey will not be able to carry out any military training and exercises in the Aegean. It will lose the capability and flexibility to organize the defense of her shores as there will be practically no international maritime areas and airspace left. Turkish Naval units will have to cross Greek territorial waters to enter the Aegean and to pass from the Aegean to the Mediterranean. The Aegean will be closed to military aircraft as well. Aegean bound flights will not be possible and Mediterranean flights will be subject to Greek permission. 10 Furthermore, Turkey will not be able to engage in activities such as scientific research, fishing, sponge-diving in the Aegean beyond its territorial sea without Greek approval. d) Greece will gain unjustified advantage in delimitation of other maritime jurisdiction areas. Since the issue of territorial waters is very much interrelated with other Aegean disputes such as the delimitation of the continental shelf, exclusive economic zone, air space related problems, etc., expansion of Greek territorial waters in the Aegean will have a direct impact on the settlement of these issues. The consequences of any extension of the Greek territorial waters in essence, are not limited to the internationally recognized navigational rights and freedoms as presented by Greece but extend far beyond that. The 12 mile limit envisaged in Article 3 of LOS Convention19 is neither compulsory nor a limit to be applied automatically. It is the maximum breadth that may be applied if conditions allow. Article 3 should only be applicable together with article 300 of the said Convention which reads as follows: "States, Parties......shall exercise the rights, jurisdiction and freedoms recognized in this Convention in a manner which would not constitute an abuse of right" Article 300 therefore poses a clear limitation for states in exercising the rights derived from the Convention. The extension of the territorial sea by Greece beyond 6 miles, in total disregard of the special characteristics of the Aegean and of the inherent historical rights that each of the coastal states have on it and in a manner to deprive Turkey of its legitimate rights would clearly and unequivocally constitute an abuse of right. At the same time, article 15 of the Convention also brings obligation for states to take into consideration the historic title and the special circumstances as far as the delimitation of territorial waters is concerned. Turkey, therefore, has long been advocating that any acquisition of new maritime areas in the Aegean (territorial waters, contiguous zone, exclusive economic zone, 19 http://www.un.org/Depts/los/convention_agreements/convention_overview_convention.htm 11 fisheries zone etc.) should be fair, equitable and based on the mutual consent of both Turkey and Greece. Therefore, any unilateral action aiming at enlarging maritime jurisdiction areas in the Aegean should not be allowed for the aforementioned reasons. In fact, both Turkey and Greece have committed themselves to refrain from unilateral acts in the Aegean by the Madrid Declaration of 1997. It is worth mentioning that the Madrid Declaration is a guiding document for Turkey and Greece which should be respected unreservedly by both countries. The Declaration contains a commitment to refrain from unilateral acts which is directly related to the preservation of the 6 miles territorial waters. It is not by coincidence that the first principle of the Madrid Declaration underlines that both sides will refrain from unilateral acts since the opposite will upset the balance established by the Lausanne Treaty of 1923. Adherence to the principles included in the Madrid Declaration of 8 July 1997 and particularly to the commitment to the present breadth of territorial waters which constitutes the core of all Aegean problems will no doubt have a positive impact on the settlement of these problems20. The view from Athens Greece has maintained six nautical miles of territorial sea since 1936. As soon as Turkey expanded her claims on the continental shelf, Greece started considering the possibility of extending her territorial seas to twelve nautical miles an act, which had already been adopted by many countries and was later incorporated in the 1982 Convention on the Law of the Sea21. The delimitation of the lateral limits of the territorial waters of a coastal State is ruled by Art. 3 of the 1982 U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea (LOSC). The language of this Article confirms, in a very clear manner, the principle that the coastal State has the right unilaterally to decide when and to what extent it is going to apply the 12-mile limit. Consequently, there is no obligation for the coastal State to ask for the approval of any neighboring State in order to establish the breadth of its territorial sea22. Besides this, Greece claims that Turkey is bound by the Convention for it has become a customary rule 20http://www.mfa.gov.tr/MFA/ForeignPolicy/Regions/EuropeanCountries/EUCountries/Greece/GreeceLinks/T erritorial_Waters.htm 21 According to article 3 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea “every State has the right to establish the breadth of its territorial sea up to a limit not exceeding 12 nautical miles, measured from the baselines determined in accordance with this convention.” 22 Even the European Union in a plan presented by the Commission in the 27 th of April (1978) was calling its member states to apply the 12-mile limit. Journal Official des Communautes, C146, 21, Juillet. 1978. p.11 12 of International Law due to the consistent state practice to that end23. What is more, Turkey’s territorial seas in the Aegean are also six nautical miles but they extend to twelve in the Black Sea and the Mediterranean. The Turkish allegations are not compatible with the International Law and practice. The Law of the Sea does not mention or insinuate that the 12-mile limit right differentiates depending on the special circumstances that exist in each sea (provided that there is enough implementation space). It is undeniable that the Aegean Sea falls under the definition of enclosed or semi-enclosed seas laid down in Article 122 of the 1982 LOS Convention but it is also indisputable that the Convention does not contain any special rules on questions such as delimitation or navigation for enclosed seas24. Greece claims that if she were to extend its territorial waters to 12 miles and thus deprive the southern entrances of the Aegean basin of the high seas corridors, the freedom of navigation would be preserved to the extent that the innovatory transit passage would come into play. What is more Greece, as a maritime country, is highly interested in the freedom of navigation and could never set obstacles to international navigation.25 A possible extension of the Greek territorial waters to 12 miles would settle yet two facets of the Aegean dispute, namely the problematic width of Greek airspace and the continental shelf delimitation dispute. Concerning the “Greek lake” argument, one could understand better if Turkey objected specifically to a12-mile territorial sea around certain islands such as Lesvos, Chios, Samos, Ikaria or Rhodes, which would be somehow “interposed” between the Turkish territorial sea and the high seas. However, Turkey adopts a maximalist approach contesting the Greek right to 12 miles in the Aegean Sea as a whole, that is to say even in areas where a Greek 12 mile territorial sea cannot be deemed to affect directly Turkish interests (for example along the eastern Peloponnesian coast, Souda base or Cape Sounion) 23 H. Athanasopoulos, Greece, Turkey and the Aegean Sea, A Case Study in International Law, McFarland, 2001, p.70. 24 “At the most, Article 123 provides for a loosely defined duty of co-operation and co-ordination among bordering states, and this exclusively in matters of conservation and exploitation of living resources, the protection of the marine environment, and scientific research programmes”. George P. Politakis,1995, p.508 25 Alexis Heraclidis, Greece and the Danger from the East, Athens, Polis, 2001, p.213-214. 13 b. The National Airspace In accordance with International Law (Articles 1 and 2 of the Chicago Convention of 1944 on Civil Aviation) the sovereign airspace of a state is the airspace above its territory and its territorial waters. For the time being, Greece has fixed the lateral limits of its territorial sea in two different ways: a 6-mile territorial sea, for general purposes, established by Law in 1936, with a 10-mile territorial sea, established by Decree in 1931 for aviation and air policing purposes. Following this arrangement, the lateral limits of Greece's national airspace were legally defined at 10 n.m., with reference to the delimitation of a special zone of territorial sea of 10 n.m., serving the requirements of aviation and air police. The reason for this "double" arrangement was Greece's policy of facilitating the freedom of navigation at that time. Indeed, in 1931, quite in conformity with international law, Greece could have created a 10-nautical mile territorial zone of general application. However, Greece refrained from doing so out of liberalism towards maritime navigation. In defiance of any legal and historical fact, Turkey questions the lateral limits of Greece's national airspace, defined as 10 n.m., despite the fact that Turkey itself has respected the above-mentioned status for 44 consecutive years (from 1931 to 1975)26. 3. The Athens Flight Information Region (FIR Athens) The International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO)27 constitutes the regulatory framework for the international legal status of airspace. It has the objective to facilitate, direct and provide communications to civil and commercial international air traffic28. Airspace, national and international, has been divided into nine Air Navigation Regions, each one including several Flight Information Regions (FIRs), submitted to the jurisdiction of the states of the Region. As a principle, each member state would be assigned an area of responsibility (FIR), within which the competent national authority exercises the control of air traffic, while providing flight information and search and rescue services. A nation control of its FIR does not mean an act of sovereignty29. The delimitation of the Athens Flight Information Region was agreed to at the Regional Air Navigation Meetings of 1950 in Istanbul, 1952 in Paris and 1958 in Geneva. The 26 www.mfa.gr The creation of the ICAO was provided by the Convention on International Civil Aviation, signed on December 7, 1944 in Chicago. 28 H. Athanasopoulos, Greece , Turkey and the Aegean Sea: A Case Study in International Law, McFarland,2001, p.74 29 www.mfa.gr 27 14 ICAO Council unanimously approved the decisions of these meetings. Turkey participated in all these Meetings and fully accepted their decisions concerning the delimitation of the Athens FIR, the boundary between Athinai (Athens) and Istanbul FIR included. The Athens FIR covers Greek national airspace as well as certain areas of international airspace 30. In accordance with the ICAO regulations and with international practice, all aircraft, civil and military alike, must submit proper notification before crossing the FIR boundary. Nevertheless, in August 1974, Turkey arbitrarily issued NOTAM 714 (Notice to Airmen) by which it unilaterally extended its area of responsibility up to the middle of the Aegean, within the Athens FIR31. Greece then had to declare that part of the Aegean a dangerous area (NOTAM 1157). The ICAO addressed an appeal to both countries to put an end to the situation, without success at the time. Finally, in 1980, Ankara withdrew NOTAM 714, when it realized that it was prejudicial to its interests and especially to its tourist industry. Nevertheless, Turkey continues the policy of committing numerous infringements of the Air Traffic Regulations within the Athens FIR and, even worse, an increasing number of violations of Greek National Airspace over sea and land in the Aegean, by the unauthorized penetrations of her military aircraft, on the pretext that the Chicago Convention does not concern military aircraft. On top of that, Turkey tries to persuade the ICAO to amend the international legal status of airspace in the Aegean by altering the air corridors in it. The Greek position is that the ICAO provisions and decisions must be fully respected. In this framework, reasons of safety of international air-traffic demand that Turkish warplanes submit flight plans when entering the Athens FIR. The Greek Air Force, in accordance with ICAO provisions, intercepts for identification purposes every unknown aircraft that enters the Athinai FIR without proper notification, as mentioned above. Turkish commentators argue that Greece is abusing her responsibility for the Athens FIR in an attempt to reduce the international airspace within the Aegean, as if it were a sovereign right, and it advances her claims towards a 12nm territorial sea limit by default32. Turkey has two main targets. First, Turkey tries to persuade the ICAO over the ineffectuality of the Greek FIR by frequently conducting violations, military exercises and by modernizing her FIR’s in order to attract the ICAO’s attention and interest.Second, Turkey wants to throw a clearly international issue into the “Greek-Turkish bilateral issues basket”. In this framework, if Greece and Turkey ended in a negotiation’s table over the 30A.Yokaris, The Flight Information Regions: The international legal status of the Athinai FIR, EKEM, Ant.N. Sakkoulas, p.11-13. 31 This line coincides with the continental shelf claims. E Dousi, The Turkish Contestations: Legal and Political Aspects, Defence Analysis Institute, Athens, 2001, p.26 32 www.mfa.gr 15 FIR issue and Greece decided to make a trade-off , then there is high probability that the ICAO would be in favor of such an agreement, making the Turkish visions a reality. 4. The Military Status of the Islands of the Eastern Aegean Sea One of the basic issues between Turkey and Greece in the Aegean Sea is the demilitarized status of the Eastern Aegean Islands. The Eastern Aegean Islands are demilitarized by several international agreements which impose legal obligations binding upon Greece. The legal instruments setting up a demilitarized status for the Eastern Aegean Islands can be summarized from an historical perspective as follows : a) 1913 Treaty of London: The future of the Eastern Aegean Islands have been left to the decision of Six Powers in Article 5 of the Treaty of London. b) 1914 Decision of Six Powers: The islands of Lemnos, Samothrace, Lesvos, Chios, Samos, and Ikaria and others under Greek occupation as of 1914 were ceded to Greece by the 1914 Decision of Six Powers (England, France, Russia, Germany, Italy and AustriaHungary) on the condition that they should be kept demilitarized. c) 1923 Lausanne Peace Treaty: In Article 12 of the Lausanne Peace Treaty the 1914 Decision of Six Powers was confirmed. Article 13 of the Laussane Treaty stipulated the modalities of the demilitarization for the islands of Lesvos, Chios, Samos, and Ikaria. It imposed certain restrictions related to the presence of military forces and establishment of fortifications which Greece undertook as a contractual obligation to observe stemming from this Treaty. The Convention of the Turkish Straits annexed to the Lausanne Treaty further defined the demilitarized status of the islands of Lemnos and Samothrace. It stipulated a stricter regime for these islands, due to their vital importance to the security of Turkey by virtue of their close proximity to the Turkish Straits. d) 1936 Montreux Convention: The Montreux Convention did not bring any change to the demilitarized status of these Islands. With the Protocol annexed to the said Convention, the demilitarized status of the Turkish Straits has been lifted to ensure the 16 security of Turkey. In the Montreux Convention there is no clause regarding the militarization of the islands of Lemnos and Samothrace. e) 1947 Paris Peace Treaty: The demilitarized status of Eastern Aegean Islands was once again confirmed in 1947 long after the Lausanne Treaty. The "Dodecanese Islands" namely Stampalia, Rhodes, Calki, Scarpanto, Casos, Psikopis, Msiros, Calimnos, Leros, Patmos, Lipsos, Symi, Cos and Castellorizo were ceded to Greece on the explicit condition that they must remain demilitarized (Annex 6). The demilitarization of the Eastern Aegean Islands was due to the overriding importance of these islands for Turkey's security. In fact, there is a direct linkage between the possession of sovereignty over those islands and their demilitarized status. Greece, in this respect, cannot unilaterally reverse this status under any pretext. However, despite the protests of Turkey, Greece has been militarizing Eastern Aegean Islands since the 1960's in contravention of her contractual obligations. These acts of Greece have become a vital dispute between the two countries. From a mere point of view to respect international law, it should be underlined that Greece also introduced a reservation to the compulsory jurisdiction of International Court of Justice on the matters deriving from military measures concerning her "national security interests" when she accepted the Court’s jurisdiction in 1993. In so doing, Greece aims to prevent a dispute concerning the militarization of the islands to be referred to the International Court of Justice33. Chapter Two NATO AND THE GREEK-TURKISH CONFLICT NATO continues to build closer cooperation on common security concerns with the European Union and with states in Europe, including Russia, Ukraine and the states of Central Asia and the Caucasus, as well as with states of the Mediterranean and the Broader Middle East. Today, we have taken decisions aimed at strengthening these relationships further in order to cooperate effectively in addressing the challenges of the 21st century. -NATO Istanbul Summit34- 33http://www.mfa.gov.tr/MFA/ForeignPolicy/Regions/EuropeanCountries/EUCountries/Greece/GreeceLinks/Mi litarization_Of_Eastern_Aegean_Islands.htm 34 http://www.nato.int/docu/pr/2004/p04-097e.htm 17 The meanings of security, defense and national interests have changed. By the end of the Cold War, NATO’s legitimacy, tasks, capabilities and new roles have been discussed widely that the Alliance is transforming and expanding its tasks to new parts of the world depending on the changing dynamics of international relations. After the dissolution of the Soviet threat, the strategic importance of the Alliance shifted to the Balkan-eastern Mediterranean zone where Greek-Turkish interaction takes place. The importance of Eastern Mediterranean, Greek islands, Turkey’s military contribution to NATO with her geo-strategic importance and the question of what happens to NATO’s credibility in the international arena if two of its members fight against each other, are vital issues that demand mutual attention of Greece and Turkey. The formation of the notion of European security, Turkey’s membership or strategic partnership to the European Union and NATO’s expanding roles, put much more emphasis on solidarity and harmonization of related policies between two members of the NATO, Greece and Turkey. Greece’s long standing objective within the NATO alliance is to play a stabilizing role in the Balkans and the eastern Mediterranean. For this purpose, it is restructuring and upgrading its armed forces in response to the new security environment and to various potential instabilities. The aim is to achieve a cost-effective, flexible and efficient force structure which can ensure a robust defense of the national territory (mainly from the Turkish threat), and contribute to NATO and regional stability. However, it is not clear that Greece can do both. NATO is encouraging Greece to boost its land forces for use in the Balkans. The logic of the Turkish threat is emphasis by Greece on air and naval forces. Moreover, the modernization of the Greek armed forces is expected to result in a more efficient Greek participation in missions undertaken by the NATO alliance. Since 1991, Greece has demonstrated its commitment to the new NATO dogma by its participation in the Implementation Force or Stabilizing Force in Bosnia (IFOR/SFOR) and in Kosovo (KFOR). However, the five-year modernization plan also has the dual aim of facing the imminent threat from its neighbor and NATO ‘ally’ Turkey35. Greece has been characterized as a strategically located, medium-sized power which managed to be an integral part of the western multilateral institutions such as NATO and the EU. Given the new role of NATO in the post Cold-War era, Greece has managed to 35 Moustakis, Fotios. The Greek-Turkish Relationship and NATO. London: Frank Cass Publishers, 2003. 18 meet the challenges and the engagements of the new NATO whose main objective is to provide the values of collective defense and collective security to its members. A half century after Turkey joined the NATO, many of the geo-political facts that justified its accession still hold. Even though there were new crisis of confidence and trust which created strains in the alliance the bonds between Turkey and NATO are secure, especially after the active role that Turkey played during the Gulf War. Throughout the Cold War period, Turkey’s geo-strategic location and the size of its armed forces, constituted an important contribution to NATO’s strategy of deterrence. Greek-Turkish differences in the Aegean stem partly from the geographical peculiarities of the region, and partly from the respective historical perceptions of the disputants. Contrary to what many Greeks believe, the conflict according to the Turks arises not because Turkey challenges Greek sovereignty over the Aegean, but Greece utilizes the Aegean islands in order to achieve complete sovereignty over the entire Aegean. Various Greek advances in the Aegean since the 1930s are viewed by the Turks as manifestations of a revisionist policy36. Turkey’s value to the Alliance was significantly enhanced via the use of major installations. İncirlik base still provides basing for US tactical fighter bombers; Sinop, electromagnetic monitoring; Kargaburun, radio navigation; Belbasi, seismic data collection; Yumurtalik and İskenderun, contingency storage of war reserve materials, ammunition and fuel and Pirinclik, radar warning and space monitoring. Along with numerous secondary facilities, which include fourteen NATO Air Defence Ground Environment early warning sites. NATO and US officials regarded Turkish military bases as being of significant value for NATO contingencies. Turkey has the second-largest army in the Alliance37. Within the new European architecture, Turkey’s growing importance is clearly related to its central location within regions of high instability and conflict. The 2004 NATO Summit in Istanbul reiterated Turkey’s importance for the alliance due to its centrality in enormous geographical regions and its military contributions and culturalhistorical relations with the extended geographies pronounced under NATO tasks. Besides, since 1991 Turkey has participated in NATO operations in the Bosnian crisis and in Kosovo, many western policy analysts and Turkish strategic planners perceive Turkey as a regional power capable of forging peace in a wider conflict zone. The southern flank of NATO 36 37 Ibid. Ibid. 19 presents the alliance with a range of challenges potentially more critical than those that NATO faces in other regions within Europe38. A possible Greek-Turkish confrontation is detrimental to the stability of the Balkan region and the cohesion of NATO. Despite current western rhetoric NATO membership does not itself create a pluralistic security community for all its members39. Greece’s and Turkey’s defense and foreign policy establishments have been shaped mainly by a realist world view. The mutual suspicion and hostility between them has remained unaffected by the end of the Cold War. Chapter Three ATTEMPTS FOR RESOLUTION Turkey and Greece have long-standing common issues of suffering, which demands to be dissolved in common interests of two countries for the sake of both themselves and of the international organizations of which they are members of. The vital points and current/possible opportunities in the Turkish-Greek conflict, particularly in the Aegean Dispute are as follows: The regulatory effect of the EU The Role of UN, international grounds on which Greece and Turkey can act cooperatively Shifts in foreign policy makings of countries, AK Party government’s quantum-leap in Turkey and its interest in conflict resolution tools for foreign policy. Increasing role of second-track diplomacy and civil-society in Greece and Turkey. In an international system where fear and distrust of other states is the normal state of affairs, the issue of relative power is of vital importance, and it is difficult to measure that. “What seems sufficient to one state’s defence will seem, and will often be, offensive to its neighbours. Because neighbors wish to remain autonomous and secure, they will react by trying to strengthen their own positions. States can trigger these 38 Bac, Meltem Muftuler. Turkey’s Relations With a Changing Europe. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1997. 39 Moustakis, Fotios. The Greek-Turkish Relationship and NATO. London: Frank Cass Publishers, 2003. 20 reactions even if they have no expansionist inclinations. This is the security dilemma” 40. Greece and Turkey have been suffering political, economical and cultural reflections of security dilemma. They are the two NATO members whose defense expenditures are too high with “5.5 per cent of GNP, $5 billion per annum for Greece, and approximately 4.5 per cent of GNP, $8-10billion for Turkey41. These resources, with human capital and historical interaction of cultures can be turned to account by canalizing them to common educational programs and foundations. Civil society organizations and second-track diplomacy should be enhanced to provide support of the public opinions and enough space for diplomatic maneuvers for political authorities. Although language is the base of civilization, the way to transfer knowledge and a key to enable one who is interested in the background of a culture, and Greek and Turkish are two means of reaching a rich political, philosophical and cultural legacy; Turks and Greeks do not know each other’s language, so their sensitivities as well. Nevertheless, common educational foundations / graduate programs in at least three languages (Greek, Turkish and English) is a pre-requisite of neighbor generations in the 21st century whether Turkey becomes an EU member or not. The EU, standing on the Acquis Communitare, functions as a regulatory mechanism and the EU law, regulations, directives, etc. have binding effects on Member States’ laws and actions. Europe is also trying to establish its own security and foreign policy which requires not only harmonization of national laws but also harmonization of Member State’s foreign policies, perceptions of and reactions to international developments. The enhancement of EU’s foreign policy and security tasks inevitably entails the decrease of a possible confrontation between Turkey and Greece even if Turkey would not be a member of the Union, because the results and political, social, economical and also strategic costs of such a confrontation shall increase a lot. Throughout the EU integration process, search of common interests and co-operative policies are inevitable for Greece and Turkey, not necessarily because of good will but owing to the mechanism of which they are a part of (Turkey is willing to be). The UN is another common ground where Turkey and Greece can act and feel need to act together especially after the shifting dynamics of international relations in the 21st 40 Barry R. Posen. “The Security Dilemma and Ethnic Conflict”. Ethnic Conflict and International Security. Brown, Michael. (Ed). Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993. p.116. 41 Dokos, Thanos. P. “Tension-Rduction and Confidence-Building in the Aegean”. Aydın, Mustafa & Ifantis, Kostas. (Ed.) London and New York: Routledge, 2004. 123-145. 21 century towards US’ unilateral acts on world politics. However, the UN is not interested much in what happens between its members like it matters for the EU. Changes in foreign policy makings of countries and the tools of diplomacy vary according to governments’ perceptions. Since 2002, AKP government in Turkey started a quantum-leap in Turkish foreign policy which “relied on a combination of traditional diplomatic and conflict resolution tools. The combination can be referred to as a balanced one: 59 % to 41 %”42. However traditional diplomatic toolbox still had a slightly larger share in comparison to CR tools, AKP government has a vital initiative towards a more active foreign policy including resolution of conflicts concerning Greece and Turkey’s EU bid. A research on AKP Government’s Foreign Policy, a content analysis, shows the shifts in Turkish Foreign Policy for the period from November 2002 to December 2004. The data used was composed of the statements and intentions of AKP, which were made public through mainstream newspapers and websites. A total of 1873 entries were codified and categorized with the aim of examining the toolbox AKP applied while conducting its foreign policy. The same data was also categorized along the issues it dealt with. 1200 1000 800 Column A Traditional Diplomacy Column B Conflict Resolution 600 400 200 0 Traditional vs CR 42 Ozalp, E. & Bozbag, F.M. & Ersoy, M. & Karaege, M. & Kesler, A. & Agirdir, Y. & Paker, D. & Tezel, A. O. AKP Government’s Foreign Policy: Content Analysis, Final Project for the Course: Foreing Policy and Conflict Resolution, 2004-2005. 22 From the total of 1873 entries, 1106 entries fall into Column A Traditional Diplomacy, whereby 760 entries were codified under Column B Conflict Resolution43. Negotiation 300 Mediation/Arbitration 250 Interactive Conflict Resolution CR Training 200 150 Economic Aid 100 Investing in Institutions Bilateral Cooperative Programs Political Incentives 50 0 Conflict Resolution CONFLICT RESOLUTION 46,1% 43 21,8% 20,9% CR TRAINING ECONOMIC AID POLITICAL INCENTIVES 0,3% BILATERAL COOPERATIVE PROGRAMS 0,0% 2,4% INVESTING IN INSTITUTIONS 0,3% INTERACTIVE CONFLICT RESOLUTION MEDIATION/ARBITRATION 8,3% NEGOTIATION 50,0% 45,0% 40,0% 35,0% 30,0% 25,0% 20,0% 15,0% 10,0% 5,0% 0,0% Ibid. 23 25,5% 30,0% 28,1% ISSUES PERCENTAGE CHART 18,0% 25,0% 20,0% 5,0% 0,8% ASIA OTHERS 0,3% CAUCASUS/ASIA 1,9% 0,7% CAUCASUS TERRORISM 1,1% ARMENIA IRAQ 0,4% BALKANS 7,9% 0,6% RUSSIA CYPRUS/EU CYPRUS/GREECE CYPRUS EU 0,0% MIDDLE EAST 1,1% EU/GREECE 1,7% GREECE 0,4% 2,2% 0,2% IMF USA 0,5% 5,0% NATO 10,0% 3,6% 15,0% The importance of the EU, Cyprus issue with regards to Turkey’s EU membership, and its relations with Greece have an important amount in the total issues, which can pave the way to new partnerships between Greece and Turkey by confidence-building measures as first steps if there is political will. 24 Conclusions The tradition of enmity between Turks and Greeks is powerful, has a history and requires long-term policies. Their respective security and foreign policies have suffered from traits, which made positive engagement and rapprochement difficult if not possible. These included a total lack of trust, a general state of misinformation about each other, the existence of nationalist-oriented education, populist media, and overemphasis on rights rather than interests44. Conflicts on the Aegean Sea firstly demand a common understanding of dissatisfactions of each other by giving up taking care of national interests only by trying to argue on status quo but looking for mergence of those interests in a win-win situation. Trust requires repetition of positive policies to make both societies comfortable that the policies are not for once but are steps of a progress towards co-operation in the Aegean Sea. However Turks and Greeks share the same geography and a historical interaction of cultures, they do not share language, psychological background of each other. Empathy-building seems to be a crucial task to hasten the conflict resolution process, which demands long-term, planned initiatives from both parties. In a famous Spanish saying: “Traveler, there are no roads. Roads are made by walking”45. These are not only necessary for Greek and Turkish societies but also for the stability of regions with which Greece and Turkey are in interaction. 44 45 Moustakis, Fotios. The Greek-Turkish Relationship and NATO. London: Frank Cass Publishers, 2003. Kissenger, Henry. Diplomacy, New York: Touchstone Book, 1994. 25 REFERENCES Athanasopoulos H., Greece , Turkey and the Aegean Sea: A Case Study in International Law, McFarland,2001. Alford Jonathan( ed.), Greece and Turkey: Adversity in Alliance, New York, St. Martin’s Press, 1984. Aydın, Mustafa & Ifantis, Kostas. (Ed.) Turkish-Greek Relations: The Security Dilemma in the Aegean. London and New York: Routledge, 2004. Bac, Meltem Muftuler. Turkey’s Relations With a Changing Europe. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1997. Brown, Michael (Ed), Ethnic Conflict and International Security. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993. Clinton, Bill. Conference at Çırağan Palace, Istanbul: July 9th, 2002. Dousi E., The Turkish Contestations: Legal and Political Aspects, Defence Analysis Institute, Athens, 2001. Heraclidis Alexis, Greece and the Danger from the East, Athens, Polis, 2001. Higgins R., Problems and Process:International Law and How We Use It, New York, Oxford university Press Inc., 1994. ICJ Reports, Aegean Sea Continental Shelf Case, 1978, para.31 Journal Official des Communautes, C146, 21, Juillet. 1978. p.11 Kissinger, Henry, Diplomacy, New York: Touchstone Book, 1994. Kriesberg, Louis, Program on the Analysis and Resolution of Conflicts, 1990-1991 Annual Report. Syracuse: Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs, Syracuse University, 1991. Moustakis, Fotios, The Greek-Turkish Relationship and NATO. London: Frank Cass Publishers, 2003. Ott David, Public and International Law in the Modern World, London: Pitman Publishing, 1978. 26 Ozalp, E. & Bozbag, F.M. & Ersoy, M. & Karaege, M. & Kesler, A. & Agirdir, Y. & Paker, D. & Tezel, A. O. AKP Government’s Foreign Policy: Content Analysis, Final Project for the Course: Foreing Policy and Conflict Resolution, 2004-2005. Politis S., “The Legal Regime of the Imia Islands in International Law”, Revue Hellenique de Droit International, Edition Ant.N. Sakkoulas ,54eme, 1/2001, p.360 Politakis George P., “The Aegean Agenda: Greek National Interests and the New Law of the Sea Convention”, The International Journal of Marine and Coastal Law, vol.10, no.4, 1995, p.507. Yokaris A., The Flight Information Regions: The international legal status of the Athinai FIR, EKEM, Ant.N. Sakkoulas. www.mfa.gr http://www.mfa.gov.tr/MFA/ForeignPolicy/Regions/EuropeanCountries/EUCountries/Greec e/GreeceLinks/Militarization_Of_Eastern_Aegean_Islands.htm http://www.nato.int/docu/pr/2004/p04-097e.htm http://www.mfa.gov.tr/MFA/ForeignPolicy/Regions/EuropeanCountries/EUCountries/Greec e/GreeceLinks/The_Aegean_Status_Quo_Historical_Perspective.htm http://www.mfa.gov.tr/MFA/ForeignPolicy/Regions/EuropeanCountries/EUCountries/Greec e/GreeceLinks/The_Delimitation_of_the_Aegean_Continental_Shelf.htm http://www.mfa.gov.tr/MFA/ForeignPolicy/Regions/EuropeanCountries/EUCountries/Greec e/GreeceLinks/Territorial_Waters.htm http://www.un.org/Depts/los/convention_agreements/convention_overview_convention.ht m http://www.cyprus-conflict.net/treaty_of_lausanne.htm 27 28