Postmodernism and Postructuralism

advertisement

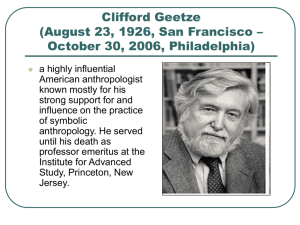

Postmodernism and Postructuralism: An Introduction I. Postmodernism: a. A mood: a critique of modernity that builds upon its ideas and does not aim at transcending modernity. i. A distinctive self-awareness and a new metacultural stance. ii. Began first in art and architecture, with the sense futility and failure in distinguishing between true art and non-art. iii. Erosion of objective grounds in the humanistic disciplines and some of the social sciences, e.g. anthropology. b. Modernity: considered to be a radical break in universal history. i. Set of concepts linked with the notion of progress ii. Eventual triumph of reason against emotion iii. Science against religion and magic iv. Truth against prejudice, e.g. Weber’s vision of ‘progressive rationalization’ and disenchantment. v. Ever-changing: everything solid melts into air. vi. Assumed the irreversible character of modernity. vii. Processual and essentially unfinished, always moving. c. Postmodernity: sees the kingdom of reason as the self-definition of European elites that contained its own exclusions. Whereas modernity saw itself as universal, and rarely even conscious, modernity itself it is now seen to be partial. i. All previous theories had aimed at a single causal explanation for understanding human history; a grand scheme: 1. Marx and the theory of class struggle. 2. Freud and the relation between ego and the unconscious. 3. Levi-Strauss and the theory of unconscious structures of meaning. ii. These Grand Theories are referred to as metanarratives. iii. Postmodernity gives up the search for grand theories and metannaratives. iv. Like Said, posmodernists believe that no-one occupies an Archimedean point beyond the power and cultural relations in which s/he is embedded. v. Difficult to categorize, because it resists categorization, seeing categorization itself as a totalizing procedure that excludes, by definition. II. Posmodernism in Anthropology, e.g. Crapanzano a. Sees previous anthropology as constructed through a conversation with an implicit, but unconscious modernity, i.e. its Western audience. b. Even Geertz, the interpretive anthropologist, comes in for criticism. 1 a. Although there are no objects in interpretive anthropology, only subjects, still Geertz positions himself as the Master Intepretor. b. The asymmetry between Geertz and his ‘subjects’ is shown in the rhetorical strategies of Geertz’ writing and interpretations: i. The relationship between I/you and I/they: Hildred and Clifford Geertz are always positioned as individuals, whereas the Balinese are only ‘they’; i.e. ‘they’ are a homogeneous group. No sense of individuality or of different interpretations, or of conflicts in an overarching ‘Balinese Culture.’ ii. Subtitles of his essays refer always to an audience that is Western, and often specifically American, e.g. Deep Play is a pun on Deep Throat: he colludes with his readers, who are always assumed to exist here and not there. iii. Hence, there is an erasure of various Balinese voices and a hierarchy of audiences and evaluations: the evaluation of what is a good interpretive ethnography always rests here; inside the relations of academic power. iv. Ethnographies should recognize these power relationships and celebrate multivocality in the act of writing. v. Crapanzano’s own work centres on the notion of projection: i.e. that anthropologists interact with native interpretors’ projections onto the anthropologist. Both the various interpretors’ projections and that of the anthropologist should be made explicit. Poststructuralism: Oppositions and their Deconstruction I. Remember de Saussere: language is a system of differences, and each signifier is defined through a relation with another signifier. a. Derrida: Landuage is a system of differences, but that is all it is. i. He rejects the distinction between language and parole. ii. He also rejects the distinction between signifier and signified: both of these oppositions reflect de Saussere’s phonocentrism. iii. Phonocentrism assumes a privileged relation existing between signifier and signified, which does not exist. iv. It is based on a hidden opposition in de Saussere’s edifice between written language and spoken language. v. There is no fixed relation between the signifiers and the signified; language consists only of signifiers: look up a signifier in any dictionary, and you find only other signifiers, not any signifieds. 2 vi. This means that there is no meaning outside of language and that meaning is created through language. II. Reversing Hierarchies of Opposition a. In any modernist philosophy, there is a logos, the key idea upon which it rests. b. However, the existence of a key idea also means that its opposite has been rejected and displaced. c. Its opposite exists as a kind of gap; a marginalized other, whose ejection forms the basis of the entire system, e.g. de Saussere’s rejection of spoken language. d. Hence, there is always a hierarchy of distinctions in any philosophical system. e. Examples: phonocentrism and logocentrism. III. Language, Differance, and Difference a. Language consists of a continual play of signifiers. b. Beyond language, there is only experience, or the residual of meaning, termed differance, by Derrida. c. Language works up and constitutes subjectivity through differences, thus transforming difference into ‘difference’. d. The goal of analysis is to find the gap which a linguistic system marginalizes, and then to unravel the hierarchy. e. E.g. gender relations: other of mankind was woman, other of ‘woman’ was colonized woman, with each term reversing the previous hierarchy. f. Everyone occupies multiple subjectivities and roles: Derrida recognizes that no single subjectivity can be considered final, there is no end point to the analysis, but only a continual play of signifiers. IV. In the Realm of the Diamond Queen: a poststructuralist ethnography? a. Considered one of the most innovative ethnographies of recent decades. b. Exploration of ‘marginality’: of the excluded in both discourse and history. i. Sees the Meratus Dayaks as marginalized not only by Dutch colonialism, but also by various forms of ethnicity and nationalism, and pre-colonial kingdoms, by distinctions between written and oral cultures, and by the distinctions between ‘the settled’ and the ‘nomadic.’ ii. Also between Islamic plains and the ‘animist’ hills. 3 c. Not only interrogates the concept of a unitary culture, but tries to recreate the experience of marginality in the text. i. Hence, descriptive lines characteristic of typical ethnographies are interspersed with geographic details, personal stories, interventions into cultural theory, stories of Meratus shamans, etc. ii. Not only that, but since the Meratus Dayaks are a mobile people, she has characterized her book as a traveling ethnography, attempting to recreate the experience of movement in the style of her text. She originally tried to find ‘a village’ to study in, yet found there were not villages to study. Lacking a stable community group with which to ‘settle’ it seemed best to move around. Her style mimics this movement, refusing to be pinned down into a local community or a temporal stopping point. She argues that the Meratus Dayaks also have to struggle with this multiplicity of identifications. iii. Believes that the attempt to create generalizations and generalizing theories are doomed to marginalize certain groups and hence become totalitarian. iv. Also stresses the existence of multiple voices from within even very local experiences. 4