A fundamental issue in the study of language is the human capacity

advertisement

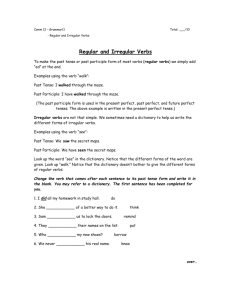

Ambiguity and frequency effects in regular verb inflection Mary L. Hare Bowling Green State University Michael Ford and William D. Marslen-Wilson Brain and Cognition Unit, Cambridge University Frequency and Ambiguity effects in English verb inflection An important issue in lexical representation, and in cognitive science more generally, is whether regularly inflected nouns and verbs are represented and accessed in a qualitatively different way than are irregulars. At least one influential account assumes that irregularly inflected items are represented lexically, independent of their stems, but those with regular inflection are not - instead only the stem is found in the lexicon, and inflected forms are produced through application of a rule once the stem has been. In contrast, a number of other accounts take what has been termed a fuill-listing approach, in which both regularly and irregularly inflected forms can be represented as single units. The two accounts make very different predictions about the role of frequency in the processing of regular past tense verbs. The first, or dual-mechanism, model claims that irregular past tenses are lexical items, so the frequency of use of an irregular past tense should affect its speed of access. For regular past tenses, however, access should be influenced not by past tense frequency, but by the frequency of the verb stem, which must be accessed before the past tense rule applies. By contrast, a full-listing account assumes that both regular and irregular past tense verbs have a lexical representation, so frequency of use should also have an effect on the access of regular pasts. To test between these two predictions we look at competition effects in ambiguous past tense verbs. We use two experimental tasks, writing to dictation and primed lexical decision. In both tasks the test items include regular and irregular past tense verbs with unrelated homophones, such as allowed/aloud or blew/blue. The items chosen differed in their relative past tense/homophone frequencies, so that in one condition the past tense was the more frequent reading, while in a second the homophone was more frequent. The question of interest was whether this frequency manipulation affected responses to both regular and irregular verbs, or whether effects were found for the irregulars alone. In Experiment One subjects heard a list of words and wrote a phrase or sentence containing each word. The results show strong effects of past tense frequency, with significantly more past tense responses when the past tense interpretation was more frequent than the competing homophone. The simplest explanation of these results is that subjects wrote the first item accessed when the ambiguous input was heard, and that the most frequent of the two meanings was accessed first. Crucially, this was the case for both the regular and the irregular verbs. Experiment Two tested whether the same ambiguous past tense verbs prime their stems in a lexical decision task. Here subjects heard the ambiguous form, and immediately at the offset of the spoken prime the related verb stem appeared on a computer screen in front of them. Subjects made a lexical decision to the visually presented stem. Again, we find a significant effect of past tense frequency in the Regular verbs: Reaction times are faster after test than control when the past tense prime is more frequent than its homophone, but slower after test than control when the homophone interpretation is more frequent. Importantly, regression analyses rule out the alternative explanation that stem frequency is the crucial factor. This pattern of results is clearly inconsistent with any account in which effects of past tense frequency must vary with the regularity of the verb. We discuss the implications for claims about the lexical representation of morphologically complex forms.