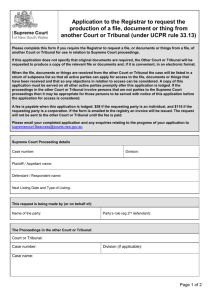

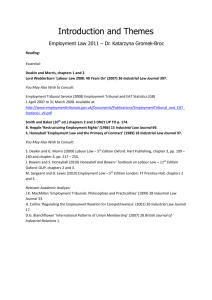

[EAT]: Employment Appeal Tribunal Judgment 24th June 1996.

advertisement

![[EAT]: Employment Appeal Tribunal Judgment 24th June 1996.](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/007301771_1-7bb2106655d43a93c65a88192bf2d2f7-768x994.png)