Childbearing on hold

advertisement

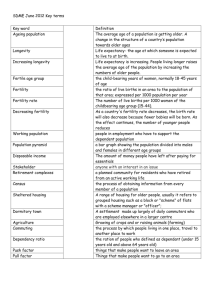

WORKING PAPER 1 CHILDBEARING ON HOLD: A LITERATURE REVIEW Roona Simpson Centre for Research on Families and Relationships Centre for Research on Families and Relationships University of Edinburgh 23 Buccleuch Place Edinburgh EH8 9LN. Email: Roona.Simpson@ed.ac.uk Contents: Page Overview 2. 1. INTRODUCTION 3. 2. THEORETICAL PERSPECTIVES 4. 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Rational Choice Theory Risk Aversion Theory Post-Materialist Values Theory Preference Theory Gender Equity Theory 3. FACTORS ASSOCIATED WITH FERTILITY DECLINE 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 The ‘Reproductive Revolution’ and Access to Contraception The Effects of Educational Attainment Conflict between Parenthood and Employment The Economic Context The Changing Character of Intimacy and Partnership Relations 4. CONCLUDING DISCUSSION 11. 19. Appendices REFERENCES 19. 1 Overview Declining fertility is one aspect of various inter-related changes in household and family structures occurring in recent decades. Fertility patterns have changed significantly since the 1960s in most European countries; fertility has reached low, even very low levels1, although there are important differences both between and within countries2. There is a vast literature from across a range of academic disciplines addressing varied aspects of fertility decline, ranging in scope from broad explanatory theories such as the Second Demographic Transition, to studies which are country-specific and/or focus on particular aspects or factors, for example childlessness or educational attainment. This literature review provides an overview of the key themes and theoretical perspectives evident in the demographic and sociological literature on fertility decline in advanced Western societies more generally, and looks at various explanatory factors associated with delayed childbirth more specifically. There are numerous determinants proposed in the literature, with many factors mutually inter-related; their relative impact is thus difficult to distinguish and/or quantify. While the strong interaction between different ‘explanatory’ factors makes any categorisation of determining factors difficult, the review looks separately at access to contraception; educational attainment; the conflict between employment and parenthood; the economic context; and the changing character of intimacy and partnership relations. It concludes with a discussion of the gaps and limitations identified in the review. 1 Demographers distinguish between three levels: i) low fertility, below replacement but at least 1.5 children per woman; ii) very low fertility, less than 1.5 but at least 1.31; and iii) lowest low fertility, that is less than 1.31 children per woman (see Appendix 1 for comparative information for countries in the EU). 2 For example Scotland has had the lowest fertility rate within the United Kingdom for two decades (Graham and Boyle, 2003); whereas the United Kingdom is categorised as having low fertility as a whole, Scotland’s TFR declined to 1.47 in 2000, that is very low fertility. 2 1. INTRODUCTION Fertility patterns have changed significantly since the 1960s in most advanced Western nations, with trends towards later childbearing, smaller families and an increase in childlessness3. Described as ‘one of the most remarkable changes in social behaviour in the twentieth century’ (Leete, 1998:3), declining fertility is one aspect of a range of demographic changes interpreted in the literature as the outcome of various societal changes (both structural and cultural) occurring as a result of modernisation. This process, the timing of which is variable across countries, is termed the Second Demographic Transition (see van de Kaa 1987; Lesthaeghe 1995)4. Whereas the decline of fertility below replacement level5 was previously viewed as the most important feature of the transition in the demographic literature (van de Kaa 1987) the postponement of first births is now portrayed as the most radical transformation (see Lesthaeghe and Neele, 2000:333; Sobotka, 2004). Fertility postponement is related to developments such as smaller family sizes and increased childlessness, all of which contribute to overall fertility decline6. This raises several issues of concern in relation to demographic ageing and its socio-economic implications (for example for social security provision), the possible decrease in labour supply and its impact on future economic growth, and the prospect of total population decline (see Bagavos and Martin, 2000)7. There is an extensive demographic literature on contemporary fertility decline, with a substantial proportion addressing the specific issue of postponement. There is also a sizeable literature within sociology considering various 3 McDonald notes that the only advanced countries that currently have replacement level fertility, the United States and New Zealand, are ‘special cases’ explained by the higher fertility of Hispanic women and teenagers (the United States) and Maori women in New Zealand (2000a:2) See also Dixon and Margo, 2006:37. 4 Broadly, this process implies diminishing constraints, an increase in behavioural options, increasing individualism and a decline in tradition. The Second Demographic Transition clearly has parallels with sociological theorising about epochal shifts in modes of behaviour in the context of late modernity, for example Giddens’ (1991, 1992) arguments about reflexive modernisation and Beck and Beck-Gersheim’s (1995, 2002) individualization thesis. 5 The replacement level of fertility is the level at which the population of a society, net of migration, would remain stable. In contemporary societies this occurs with a total fertility rate of around 2.1. The total fertility rate is a measure that expresses the mean number of children that would be born to a woman if current patterns of fertility persisted throughout her childbearing life. 6 Some authors suggest rather that delayed childbearing constitutes a ‘postponement transition’ towards a latefertility regime (see Kohler, Billari and Ortega, 2002: 659-661). 7 Increasing concern about the possible consequences of fertility decline is evident in numerous articles and reports commissioned by the European Union, some of which are reviewed here. The need to address fertility decline is near universal in the literature, however a somewhat maverick position is taken by MacInnes (2003), who dismisses concerns about the ‘myth of population ageing and catastrophic population decline’ as ‘neoconservative rhetoric’, arguing that as ageing is socially constructed, increasing standards in health and activity mean the capacities and productivity of future elderly cannot be determined. 3 aspects of fertility decline, ranging from broad explanatory theories to small-scale studies looking at the experience of particular statuses, such as childlessness. This review starts with an overview of theories seeking to explain fertility decline more generally8. The literature reviewed here includes cross-comparative studies, mainly of advanced ‘Western’ societies; where studies have specifically addressed fertility postponement and/or childlessness in Britain, these are identified. There is a considerable literature focussing on specific policy recommendations to address fertility decline (see e.g. Chesnais 1996, MacDonald 2000a, Castles 2003). This is not reviewed separately here; however, as policy recommendations reflect particular understandings of the reasons for fertility decline, the policy implications of specific theoretical perspectives are referred to below. The subsequent section considers the main determinants of delayed fertility proposed in the literature, looking separately at access to contraception; educational attainment; the conflict between employment and parenthood; the economic context, including the influence of unemployment and various forms of uncertainty; and the changing character of intimacy and partnership relations. The concluding section discusses the gaps and limitations identified in the literature. This review has considered key demographic and sociological studies looking at fertility decline. These studies were identified via a combination of online database and library searches, and through checking reference lists at the end of each paper obtained for other relevant publications. Key websites in the field were also examined. 2. THEORETICAL PERSPECTIVES This section outlines the broad theoretical perspectives underpinning explanations of fertility decline, albeit these are often implicit. There is considerable variation in the literature in the extent to which these theories seek to explain fertility decline, or identify broad areas associated with it (for example, there is some disparity in the way that institutional structures are related to fertility decline). As with the factors looked at below, there is overlap between these theories; nevertheless, these are distinguished by the relative With regards to fertility postponement, the focus here is on first births – while second and higher-order births are being postponed as well, this is mostly a consequence of first-birth postponement rather than a manifestation of change in birth intervals (Sobotka, 2004). 8 4 emphasis attributed to individual agency and social structural processes. The following draws broadly on McDonald (2000a, 2000b), and looks separately at rational choice theory; risk-aversion theory; post-materialist values theory; preference theory and gender equity theory. 2.1 Rational Choice Theory This understanding of fertility decline draws on neo-classical economic assumptions of individuals as ‘utility maximisers’ to argue that in deciding to have a child individuals make a ‘cost-benefit’ calculation. Thus, standard economic theory attributes the trend to below replacement fertility to increasing levels of female education and employment increasing the ‘opportunity costs’ of childbearing (see Becker 1991, Hotz et al. 1997). Whereas some costs can be calculated in monetary terms, the benefits refer to psychological dimensions that are not readily quantifiable. McDonald (2000a) suggests it is likely that the net benefits to be gained fall as birth order rises (that is, there is more benefit to be gained from first children, and that this decreases the more children one has); in addition, this may also apply as people get older; accordingly, as the age of becoming a parent increases people will be less likely to have additional children9. Rational choice theory implies that, in order to have a positive impact on fertility rates, the psychological benefits or economic costs of children should be respectively increased or reduced. Regarding benefits, McDonald concludes that while this may not be readily amenable to policy, a general sense that society is child-friendly may be effective. Direct costs (actual expenditure) are distinguishable from indirect costs (earnings foregone in bearing and caring for the child): these latter decline as society is organised in such a way as to enable parents to combine work and family (2000a:6). This theory, generally presented in terms of a ‘trade off’ between work and fertility at the level of the individual, has been widely criticised for failing to address the wider context in which this takes place and which impact on patterns of cross-national fertility (e.g. see 9 As such this would influence the quantum rather than the likelihood of children. The role of lifetime childlessness in fertility decline is not clear-cut in the literature. For example, McDonald states that differences between average fertility levels across industrialised countries appear to be due less to differences in the proportion of childless women than in the proportions of women having three or more children, concluding that demographic research has ‘given too little attention to the numbers of children that women are having’ (2000a:5). Sobotka similarly concludes that fertility decline appears to be driven more by declining family size than by increasing rejection of parenthood (2004:150). Berrington however argues that the increasing incidence of childlessness amongst recent cohorts of women in England and Wales is ‘the driving force behind the decline in average completed family size’(2004:9). 5 Castles 2003:218). In addition, as Folbre (1994) and others have observed, families cannot predict the future costs of children, while men and women bear these costs differently. There are certain ontological and other assumptions implicit to rational choice theory, primarily that of individuals as rational decision-makers with a good knowledge or understanding of the costs and benefits to be incurred. The limitations of this view of human nature are illustrated in the debate about the distinction between voluntary and involuntary childlessness (see Wasoff and Carty, 2004). In the literature, involuntary childlessness may be defined in relation to physiological factors preventing otherwise desired childrearing; by implication, voluntary childlessness is a status chosen by the individuals concerned. However, this distinction suggests a line between choice and fate that is not always clear-cut: for example, postponement may result in unintended childlessness, or revision of original decisions to have children as people get accustomed to a childless lifestyle and become unwilling to change their priorities. Several qualitative studies on childlessness emphasise decision-making about childbearing is an embedded, ongoing process, and that the ‘voluntary childless’ may display various degree of certainty over their decision (see McAllister and Clarke 1998; Hird and Abshoff 2000). These studies suggest ‘choice’ is a far more complex notion than rational choice theory allows. 2.2. Risk-Aversion Theory This theory builds in the uncertainty inherent in relation to anticipated future costs and benefits, and assumes that where economic, social or personal futures are uncertain, decision-makers may act to avert risk. There has been much recent academic attention to new social risks consequent on various inter-related changes occurring as part of a shift to post-industrial society (see Beck 1992, 1999; Giddens, 1994; Lupton, 1999; Taylor-Gooby, 2004)10. One aspect of this is an emerging literature on the extent to which risk aversion applies to the personal sphere and impacts on whether people form partnerships or embark on parenthood; McDonald (2000a) for example contends that young women in Japan see marriage itself as a risk to their future employment. 10 Contemporary sociological theorising about the changing nature of risk associates this with rapidly expanding choices and opportunities and argues that these in turn contribute to further anxiety and uncertainty, facilitating the avoidance of long-term commitments (see Beck 1992, Bauman 2000). There is an emerging body of empirical research examining people’s perceptions of and responses to risk in a range of areas including intimate relationships, some of which is examined here. 6 Several scholars have associated fertility decline with factors such as economic uncertainty and an increasing individualisation of risk. For example Hoem’s (2000) empirical study links declining fertility in Sweden with increased participation in higher education at a time of poor economic circumstances; observing that the proportions of young women (aged 2124) receiving educational allowances rose from 14% in 1989 to 41% by 1996, she interprets this as evidence of risk-averse behaviour (investment in future security) in a context of widespread cut-backs in government services. Hobson and Olah (2006a) relate declining fertility to changes in consciousness of women around the risks of economic dependency and divorce in the context of weakening decommodifying policies introduced in response to the effects of global economic pressures. Lewis (2006), reporting the findings of exploratory qualitative research on the extent to which individuals regard partnership and childbearing as risks, similarly situates this in a context of the erosion of the traditional family model alongside an increasing expectation of individual responsibility. Lewis suggests that greater fluidity in intimate relationships, which has given more choice to individuals in partnering, has also transformed the economic dependence on men that women have traditionally experienced from a possible source of protection into a much more straightforward risk, risk that is exacerbated on the arrival of children. Lewis thus recasts what might be interpreted as the pursuit of self-fulfilment in terms of a quest for security in face of risk and uncertainty. She argues that more state support (financial compensation for care and the provision of care services) would help reduce the additional uncertainties that respondents experienced upon becoming parents (2006:54). McDonald similarly argues that, rather than individual methods of dealing with risk (such as insurance), a well-developed welfare state may be more effective at smoothing out risks (for example, social security arrangements for job loss or health problems); he notes however that the present direction of social and economic policy in almost all industrialised countries is to pass risks away from the state and back on to individuals. 2.3 Post-Materialist Values Theory Associated with the Second Demographic Transition, this perspective contends that changes in social and demographic behaviour have been driven by the growth of values of selfrealisation, satisfaction of personal preferences, and freedom from traditional forces of 7 authority such as religion11. Several qualitative studies indicate the voluntary childless frequently report their desire for independence, freedom and spontaneity (see Fischer 1991, Lisle 1996, McAllister and Clarke 1998)12. Delayed childbearing and increased childlessness is seen as the result of fundamental social, economic and cultural transformation which has changed the norms relating to family and reproduction. Recent sociological work similarly contends that there has been a shift in personal values in a ‘postmodern’ context, and a resultant shifting ‘parental identity’ with consequences for fertility decline (see Gillespie 2001, Lucas 2003, MacInnes 2003). The theory asserts these values are associated with increases in divorce rates, cohabitation and ex-nuptial births, more prevalent in the more liberal societies of Nordic and Englishspeaking countries than in the more traditional family cultures of, for example, Southern Europe; the low divorce rates and low levels of cohabitation of these countries in contrast suggest stable relationships and higher fertility rates. However, McDonald (2000a) points to the fact that it is secular liberal societies that are experiencing higher fertility, while more traditional ‘familistic’ societies seem less well able to reproduce themselves, as evidence counter to the theory13. Similarly, he cites various studies in which younger women express preferences for numbers of children well above actual behaviour (see e.g. van de Kaa 1997) and interprets this as indicative of the influence of other factors (costs, uncertainty and the nature of social institutions) on the number of children women have14. McDonald thus emphasises the importance of considering low fertility as a societal phenomenon, rather than a reflection of individual values. This position is somewhat in contrast to the ‘preference theory’ proposed by Hakim (2003) to explain fertility decline, looked at below. Giddens’ (1992) analyses of transformations in intimacy is an example of recent sociological theoretical work in this area. He argues that contemporary partnerships (‘pure relationships’) are characterised by egalitarianism and individualism, with parenthood no longer an intrinsic aspect of such relationships. Contingent on the benefits derived by each partner (1992:58), such relationships are also characterised by inherent instability (1992:137). 12 However, such reports could also be interpreted as a defensive strategy in response to the enduring negative stereotyping of childless women in particular, also referred to in several studies (see Veevers 1980, Gillespie 2001). 13 Previously, countries with the highest period fertility rates were those with the most pronounced familyoriented cultural traditions and the lowest rates of women’s labour market participation; Castles (2003) refers to the reversal of these relationships in recent decades as these relationships as ‘a world turned upside down’. Fertility rates in Southern European countries (with the exception of Portugal) fell from the highest in Europe in the mid-1970s to the lowest by the beginning of the 1990s (see Appendix One). Esping-Anderson refers to the observation that familistic contexts such as Italy and Spain are seemingly counter-productive to family formation, as ‘the great paradox of our times’ (1999:67). 14 Dixon and Margo (2006) similarly interpret ‘the baby gap’, the shortfall between stated desired numbers of children and actual numbers born, as evidence of wider social constraints. The status of such stated preferences however is an issue of some debate and is considered further in the concluding discussion. 11 8 2.4 Preference Theory Hakim (2003) explicitly proposes preference theory, which emphasises personal values and decision-making at the micro-level, as a new theoretical framework for understanding current changes in fertility and predicting future developments. This approach is distinguished from prevalent economic theories and research focussing on macro-level correlates in cross-national comparisons, which Hakim argues fails to consider ‘the social processes and the motivations of the women and men behind these statistical measures’ (2003:351). Hakim argues lifestyle preferences are ‘the hidden, unmeasured factor that determines women’s behaviour to a very large extent’ (2003:366), classifying these as adaptive, work-centred, or home-centred. She contends this approach considers the particular social, economic and institutional contexts within which preferences become the primary determinant of women’s choices. Hakim emphasises access to modern contraception and the subsequent equal opportunities ‘revolution’ as necessary preconditions for various others social and economic changes which produce a qualitatively different scenario of options and opportunities for women, who now have genuine choices regarding employment versus homemaking. She considers the implications of her theory for responsiveness to public policy, arguing that the contemporary ‘bias against motherhood’ ignores home-centred women, and for a revaluing of reproductive work. This approach can be seen as one example of an increasing interest in changing values and attitudes in the demographic and sociological literature (see e.g. Lesthaeghe 1995; Mason and Jensen 1995; Leete 1998; McRae 1999; Castles 2003; Lucas 2003; MacInnes 2003, 2005). However, Hakim’s analysis presents preferences as fixed attributes of an individual, with little attention given to explaining the differences between women, or how preferences may change over time. In addition, this fails to consider the iterative relationship between an individual’s preferences/attitudes and the experiences their specific social context affords them. For example, a study by Santow and Brecher (1998) on southern European migrants in Australia demonstrates fertility decline preceding changes in traditional family values. A study by Bernhardt (1988, cited in Sobotka, 2004:18) shows that an increase of part-time work in Sweden in the 1970s gave rise to a ‘combination strategy’ of part-time employment and childrearing, a strategy which became common after the birth of a first child and was equally pursued by women who previously tended to stay at home and those who had worked full-time. While women and/or couples may choose their preferred mix 9 of fertility and employment in light of their own aspirations, these are shaped in the context of prevailing social values. As Castles argues, these can and do change: for example, the view of childbearing and female employment as inimical prevalent in the postwar decades is actually an ‘historical aberration’ (Castles, 2003: 218). Empirical analyses (Hakim 2005) of attitudinal data from across Europe, North America and New Zealand) aimed at testing the importance of attitudes/values between parents and the childless15 found differences to be less pronounced than expected, although greater between childless women and mothers than between men (for whom careers and income earning remain central life priorities, whether fathers or not). The proportion of individuals classified as ‘ambivalent’ about parenthood varied considerably across countries, and differed by sex (for example, a third of British women and a quarter of British men remain undecided at age 30). Despite adopting different personal choices, there was widespread support for family policies across parental statuses, and the study concluded that policy can influence the behaviour of the ambivalent group and the size of families. 2.5 Gender Equity Theory McDonald (2000a, 2000b) considers the importance of gender equity in fertility decline, arguing that low birthrates are an outcome of high levels of gender equity in individualoriented institutions, combined with persisting gender inequality within the family. He contends that whereas assumptions of a ‘male breadwinner’ model have been challenged by increasing opportunities for women in areas such as education and the market (such that these social institutions are now characterised by a high degree of gender equity) this model still underpins family-oriented social institutions (e.g. family services, the tax system, the family itself)16. This study distinguishes the ‘voluntary childfree’, those who definitely do not want children, who are consistently negative on all questions about children, and ‘uncertain childless’ by those who are gave an uncertain or ambivalent reply on at least one question concerning the desire to have children. ‘Parents’ were classified as those with children and those who plan to have children (my italics). Given the debate about defining voluntary childlessness (see 2.1 above), this classification raises various issues. It presents these preferences as static, and assumes future outcomes from stated preferences. As noted above, previous research has identified a gap between preferences re childbearing, and realised fertility; classifying together those who state a desire to have children with actual parents ignores differences between these groups (including in attitudes and values) which may impact on the likelihood of going on to have children. 16 There is an extensive literature from a variety of disciplines demonstrating the slow pace of change in the gendered division of labour, outwith the remit of this review; however, the ongoing lack of gender parity is emphasised in some studies considering patterns of partnership and fertility decline. Hobson and Olah (2006a) for example, drawing on Lewis’s (2001) notion of the ‘one and a half adult’ worker model replacing the traditional breadwinner/caregiver model, observe that even the Nordic countries are characterised by a ‘one and a third’ model. 15 10 Other scholars looking at fertility decline also address the issue of ‘domestic democracy’, for example through time-budget surveys which clearly indicate women’s continuing domestic responsibility (e.g. Joshi 1998; Esping-Anderson 1999). As Joshi notes, in ‘the private arena of home life, at least among young adults, the ideology of sex equality runs ahead of practice’ (1998:177). This poses a dilemma for women, who may increasingly perceive their family role as incompatible with individual aspirations. Gender equity theory proposes that the more traditional a society is with regard to its family system, the greater is the level of incoherence between social institutions and the lower its fertility. As McDonald argues, if women are provided with opportunities near to equivalent to those of men in education and employment but these are severely curtailed by having children, then, on average, women will restrict the number of children (2000a:10, see also Chesnais 1996, Esping-Anderson 1999). While McDonald acknowledges family organisation is fundamental to cultural identity and thus ‘revolutionary change is rarely a possibility’ (2000a:1), he argues this theory supports policy recommendations such as gender-neutral tax-transfer policies, and support of workers with family responsibilities regardless of gender. He emphasises however that it is not so much the nature of policies that matter but the nature of society as a whole (for example gender equity policies will be rendered ineffective if unemployment rates for young people are high) (2000a:21). 3. FACTORS ASSOCIATED WITH FERTILITY DECLINE This section reviews findings on the determinants of fertility decline, and draws on the work of Sobotka (2004). Within the demographic literature, several authors seeking to explain this propose a complex of determinants17. However, many factors are mutually inter-related, and their relative impact may be difficult to quantify: for example, prolonged education may delay the transition to economic independence, but may also influence fertility indirectly, through increased career opportunities or a less traditional or family17 To illustrate, Lesthaeghe (2001:17-18) lists seven general and seven country-specific factors accounting for new patterns of fertility: General: 1) increased female education and economic autonomy; 2) rising high consumption aspirations creating the need for a second household income and fostering female labour force participation; 3) increased investments in career developments by both men and women, alongside increased competition in the workplace; 4) rising ‘post-materialist’ traits such as self-actualisation and freedom of choice; 5) a greater emphasis on quality of life and rising taste for leisure; 6) a retreat from irreversible commitments and a desire for maintaining an ‘open future’; 7) rising probabilities of separation and divorce. Country-specific: 1) geographical mobility of young adults in tertiary education; 2) lack or availability of state subsidies for students (fellowships, housing, transport subsidies); 3) flexibility of the labour market; 4) youth unemployment; 5) minimum income guarantees; 6) costs and availability of housing, to meet household needs at various stages of family formation; 7) contraceptive availability and methods mix, access to abortion. 11 centred value orientation. Some determinant impact differently on men and women, different birth-cohorts and sub-populations, or their impact may change over time, while the strong interaction between different ‘explanatory’ factors makes identifying and categorising ‘causes’ of fertility decline particularly difficult. Furthermore, understandings of the role various factors play are influenced by underlying theoretical perspectives. 3.1 The ‘Reproductive Revolution’ and Access to Contraception The spread of access to modern contraception and, to a lesser extent, the legalisation of abortion are identified in the literature as important determinants of fertility postponement18. There are broadly two approaches as to their impact: one views contraception mostly as a technical factor addressing the demand for birth control (see Castles 2003), while the other sees it as instrumental to broader behavioural and cultural change (see e.g. Presser, 200119). Much of the literature emphasises the importance of contraception in facilitating the late start of fertility20, and this view is supported by evidence from several country-specific studies: for example, in Spain a dramatic increase in usage occurred in 1978 following the removal of a ban on contraception, and rapid postponement of fertility started in 1980 (see Castro Martin 1992; Sobotka 2004). Contraceptive use has been associated with prolonging the interval between marriage and first birth in Britain (see Murphy 1992, 1993). Murphy argues that the diffusion of the contraceptive pill was the main determinant of the fertility change between the mid-1960s and mid-1970s. As noted above, some of the literature links modern contraception with a change in norms and values. Those utilising the concept of the Second Demographic Transition emphasise the catalytic role of efficient contraception in the behavioural and cultural changes characterising this process. Van de Kaa for example attributes changing partnership patterns more generally, for example the spread of cohabitation and the delay and decline of 18 These arguments apply also to technologies affording women greater flexibility in family planning (for example the freezing of eggs and embryos), potentially allowing women to delay becoming a mother at an age beyond that which they would be naturally fertile. 19 Presser focuses on women, arguing that changing notions of concepts of time, resulting from the greater ability that recent cohorts of women have to control the timing of events over the life course, are an important factor explaining low fertility in industrial societies. 20 There also appears to be a link between inadequate contraceptive use, especially amongst teenagers, and a high proportion of ‘unwanted’ or ‘mistimed’ births among very young women, evident both in England and Wales and the United States (Sobotka 2004, see also Frejka 2004). 12 marriage, to the freedom from unwanted pregnancy afforded by contraception (1994:114). Sobotka (2004) observes that the widespread use of modern contraception means having children usually requires a conscious decision to discontinue pill use, an important reversal of the previous status quo wherein contraceptive efforts focused mainly on preventing additional pregnancies after the couple reached their desired family size. As such, he suggests that the increasing level of contraceptive use may further reduce the incidence of unintended pregnancies in some Western countries (particularly Ireland, the United Kingdom and the United States, as well as in most of the post-communist societies), consequently leading to an additional fertility postponement (2004:28). Within the sociological literature, Hakim (2003) and McInnes (2005) particularly emphasise the necessary character of the ‘reproductive revolution’21. For Hakim, modern contraceptive methods crucially shift control over reproduction to women; she argues the social and psychological significance of this, in terms of a sense of autonomy, responsibility and personal freedom for women, is generally overlooked by male demographers (with exceptions, e.g. Murphy 1993). She characterises the reproductive revolution as a precondition of the similarly revolutionary ‘equal opportunities’ developments which in turn enabled other changes, for example in the labour market, allowing more women the possibility of acting on their preferences re childbearing. MacInnes (2005) similarly emphasises the ‘reproductive revolution’ as the progenitor, rather than the outcome, of social change. 3.2 Educational Attainment Much of the literature identifies educational attainment as a factor associated with fertility decline generally, and fertility postponement in particular. In recent decades post- secondary education has undergone a massive expansion, and young adults throughout Europe have spent an increasing proportion of time in education, with tertiary education constituting the main route to stable employment, adequate income and career development (Kohler, Billari and Ortega 2002). Women especially have benefited from this development, and now form more than half of the graduate/postgraduate students in a majority of European countries (Sobotka 2004). This expansion impacts on fertility directly, with the period of study evidently incompatible with family formation. Prolonged 21 MacInnes (2005) does not use this term to refer to the advent of modern contraceptive methods in recent decades, but to a wide-ranging concept encompassing various societal developments occurring over several centuries. 13 education (during which students usually lack adequate resources, both income and housing, and future employment conditions are uncertain) also delays the transition to economic independence (Kohler, Billari and Ortega 2002), and several studies demonstrate ‘being-in education’ strongly reduces the likelihood of having a first child (see e.g. Blossfield 1995; Hoem 2000). As well as delay attributable to time spent in education, this influences the timing of parenthood in various other ways. That this is seen as particularly the case for women is indicated by the numerous studies investigating the influence of education on fertility decline which focus on women. Substantial differences in first birth timing according to the level of education are evident across all developed societies, with highly educated women postponing childbearing to a larger extent than women with less education, who often continue having children at early ages (Sobotka 2004:13, see also Gustaffson at al. 2002). Several country-specific studies demonstrate that the increasing educational level explains a significant proportion of the increase in the mean age of first birth over time (see e.g. Beets et al. 2001 for Holland; Martin 2000 for the US; Meron and Widmer 2002 for France; Joshi 2002 for the UK). Educational level is clearly linked to the other factors considered in this section. Higher education enhances the position of individuals in the labour market, hence increasing the ‘opportunity costs’ of childbearing22. Values and preferences are also distinguished by educational level. Some scholars link these with changing partnership patterns, with less traditional living arrangements such as cohabitation associated with delayed parenthood, statuses initially predominant amongst people with higher education. In addition, highly educated women are likely to seek more egalitarian relationships and develop higher standards concerning a potential partner’s qualities in terms of education and income; leading to delayed union formation and marriage (Oppenheimer 1994), these increased standards may contribute to further postponement of childbearing. 3.3 Parenthood and Employment Debates about the conflict between career aspirations and motherhood predominate in the demographic literature, with discussion on the difficulty of reconciling the two ‘careers’ of employment and fertility focusing on women. Traditionally seen as incompatible (a view 22 As noted above, while this is underplayed in some of the literature, this is particularly the case for women. 14 supported by neo-classical economic analyses of family formation, e.g. Becker 1991), this argument has been challenged by the ‘positive turn’ taking place in many countries in the mid to late-1980s, where higher fertility was associated with higher female labour force participation (see Brewster and Rindfuss 2000; Castles 2003; Billari and Kohler 2004). Several scholars suggest birth timing and spacing may be key strategies individuals adopt to balance work and family responsibilities (e.g. Brewster and Rindfuss, 2000:282). However, there is little distinction made between childbearing and childrearing, with women’s retention of responsibility for the latter and consequent greater burden of ‘opportunity costs’ for the most part unquestioned. In discussing this factor, many authors emphasise the importance of country-specific institutional contexts, such as family and welfare provision, employment policies and, to a lesser extent, gender equality, as hindering or facilitating childbearing and employment compatibility. This appears to be a more recent concern in the literature: Hobson and Olah (2006b) observe that, while women’s labour force participation was built into demographic models as opportunity costs for women’s fertility decisions, social policy incentives and constraints were not, and that it is only recently that the role of social policies/institutions in shaping fertility decisions has been considered. Authors taking a welfare regime approach identify Conservative (Continental) and ‘Familistic’ (Southern European) welfare regimes as having a negative impact on fertility, both on timing and quantity, by reducing the opportunity for women to have an independent career; this is in terms both of specific policies (including family benefits/childcare provision/labour flexibility) and cultural norms (see Esping-Anderson 1999; Brewster and Rindfuss 2000; Castles 2003). Much of the literature addresses part-time or flexible employment as a strategy facilitating the combination of work/childrearing amongst women. The availability of childcare is identified as enabling women to combine employment with having children, and the variation in provision across Europe (in terms of cost, availability, public/private provision) is highlighted by various authors (see Esping Anderson 1999; Castles 2003). There are several studies analysing the lack of childcare provision as a factor facilitating fertility postponement (see e..g Kreyenfeld 2002 comparing East/West Germany; del Boca 2002, on the effects of childcare and part-time work opportunities for women in Italy). The level of income for women, related to age/duration of employment, is also proposed as a factor in fertility postponement. The economic perspective of lifetime income provides a 15 very strong rationale for late motherhood23. Some scholars argue that strong employment prospects for women are now an important precondition for family formation (e.g. see Castles 2003). Sobotka (2004) observes this factor is also related to a ‘consumptionsmoothing’ motive, which assumes that couples aims at maximising increasing income over time in conjunction with the postponement of childbearing. Several empirical studies find that an increase in women’s wages is associated with first birth postponement (see e.g. de Cooman, Ermisch and Joshi 1987 on England and Wales; Heckman and Walker 1990 on Sweden). Joshi (2002), in a study considering women in Britain, analysed the life-time earnings of different categories or women and found that fertility postponement could reduce the ‘motherhood penalty’. This was particularly the case for women with a university degree: assuming maternity leave is fully paid, the model showed no loss in earning associated with first birth at age 30 (2002:455). 3.4 The Economic Context Many authors draw attention to the impact of global restructuring and welfare state retrenchment on the demographic patterns of recent decades. Alongside this, several emphasise the importance of stable employment as an important precondition for parenthood; this is identified by some as particularly important for men, with less stable employment/declining relative earnings of young men being argued as a factor in marriage postponement (Oppenheimer 1994). High unemployment rates, concentrated amongst young people, combined with precarious job security and legislation protecting ‘insiders’ on the labour market, have been identified as factors contributing to fertility postponement in Southern Europe (see Bagavos and Martin, 2000; Sobotka 2004). Employment opportunities and levels of unemployment are identified by several authors as influencing childbearing decisions, both directly in terms of economic status and also more generally by levels of well-being and existential security. Unemployment is analysed in most studies as increasing economic uncertainty and discouraging young people from union formation and parenthood (see Kohler, Billari and Ortega 2002; Prioux 2003). Hobson and Olah (2006a) interpret the association between precipitous declines in female employment A recent study on women’s lifetime incomes (Rake 2000) calculates the income loss associated with motherhood, differentiated by educational/employment status. Using a series of hypothetical individuals, the income costs of motherhood were shown to vary substantially according to the educational level of the mother, with the illustrative graduate mother experiencing a significantly smaller income loss than her lowskilled counterpart. Nevertheless, as Joshi notes, although well-educated women experience the least loss of earnings in motherhood, they are the most likely to postpone or avoid it (2002:28). 23 16 and fertility rates in transition economies such as Hungary and Poland, countries where women have been highly integrated into paid work, ars paradigm cases of ‘birthstrikes’, a reaction against a loss of jobs and uncertain labour market futures24. Unemployment is associated with instability and uncertainty, at both the societal and individual level. As mentioned previously, much contemporary sociological theorising has argued that high levels of uncertainty are conducive to the postponement of partnership and parenthood. However, Sobotka suggests this conjecture is not fully supported by the empirical findings: rather, ‘the available evidence suggests that the influence of uncertainty on first birth timings differs in time, across countries, by type of uncertainty, and has a different impact upon various population groups’ (2004:21). For example, the study by de Cooman, Ermisch and Joshi (1987) analysing fertility in England and Wales concluded that fertility reactions to economic change varied by stage in family formation, with labour market conditions influencing timing rather than the quantum of fertility. The literature on the effects of labour market conditions on fertility postponement is somewhat inconsistent, and it is difficult to drawn any overarching conclusions. While at the societal level worsening economic and employment conditions are usually associated with reduced fertility, improving labour market conditions for women may also lead to postponement. As Sobotka observes, there is still very little understanding as to how particular types of uncertainty affect individual decision-making on fertility timing and quantum, and how this decision-making is shaped by class-specific resources and aspirations (2004:22). As discussed further in the concluding section, there also appears to be little consideration in the demographic literature of the way in which such decisionmaking is also influenced by gender. 3.5 The Changing Character of Intimacy and Partnership Relations There is an extensive and varied literature considering the changing character of intimacy generally25; this review considers those works which considers these changes in relation to fertility postponement. Various inter-related trends have resulted in a profound 24 However, it has also been suggested that unemployment may motivate women to take advantage of economic inactivity and opt for childbearing instead of competing for scarce jobs. In countries with established welfare systems and generous family support arrangements, unemployment benefits may provide sufficient replacement for earned income and enhance the motivation for childbearing (Sobotka 2004). 25 For a review of recent sociological scholarship on intimacy, see Jamieson 1998. 17 transformation in household and family structures in recent decades, including the delay and decline in marriage, increasing divorce rates, the rise in cohabitation, the separation of sex and marriage and marriage and reproduction (resulting in both childless marriages and non-marital fertility), and ‘unconventional’ living arrangements including extended periods of solo living. As noted above, these changes are attributed by several scholars to shifts in societal norms and values, conceptualised broadly as the Second Demographic Transition. Here, it is transformations in ways of relating, rather than the changing family and household structures per se, which are argued as having profound consequences for fertility levels: for example, van de Kaa (2004) contends that whereas in the traditional family children were an expected outcome of marital union, in a contemporary context parenthood has become a ‘derivative’ of the individuals’ quest for self-fulfilment. However, as discussed further in the concluding summary, interpreting statistics on demographic change and attributing motivations to such general concepts as individualisation is problematic. There is empirical data supporting ideas that more complex partnership patterns are associated with late entry into parenthood. For example, a study analysing FFS data on men and women in Sweden found transition to parenthood strongly influenced by previous partnership experiences, amongst other factors. Those with longer previous union experiences (at least 3 years for men, 5 years for women) have significantly lower first birth intensity at higher ages in Sweden than those with none or short experience (Olah, 2005). Other changes, including the increasing education and labour attachment of women, have also influenced partnership and parenthood decision-making, as noted above: some scholars interpret this in terms of women’s greater independence allowing them to set higher standards in relation to partnership (see Oppenheimer 1994), with consequent delay and decline in marriage rates, and higher marital instability. For example, analysis of the 1993 FFS Survey in the Netherlands indicates 30% of women who eventually wanted to have a child and were still childless after age 30 mentioned ‘not having a suitable partner’ as a reason for postponing childbearing (see Bouwens, Beets and Schippers 1996:8). Other research indicates that gender role attitudes do influence fertility intentions. Research in the US suggests that voluntary childless women are more likely to hold egalitarian attitudes towards women’s roles and the importance of women’s paid work outside the home (Houseknecht, 1987). Research by Berrington (2004) finds that women with more egalitarian attitudes about women’s paid work outside the home are significantly less likely to intend to start a family. 18 Other studies argue that men have shown an increasing tendency to withdraw from binding commitments and parenthood in particular (Lethaeghe 1995; Goldscheider and Kaufman 1996). Goldscheider and Kaufman relate this in part to increased standards for parenthood, wherein children and fatherhood are viewed primarily as responsibility and obligation (1996:90)26. Related arguments emphasise high consumer aspirations, which imply the need for two incomes in a household, and may fuel delay of marriage and childbearing. Goldscheider and Kaufman (1996) for example contend that men frequently attach excessive importance of consumer goods, which can get priority over family formation. Sobotka considers the diminishing relative importance of childbearing in partnership unions, which he contends implies a postponement of first birth towards late reproductive ages and is an important factor ‘often neglected by commentators on delayed parenthood’ (Sobotka, 2004:25). There are now studies which seek to explain the desire to have children (see e.g. Morgan, and Berkowitz King, 2001), suggesting an interesting reversal of a previous ‘default position’ in which childbearing was assumed as natural or an intrinsic aspect of partnership (for example, qualitative studies looking at the stigmatisation of childlessness refer to ‘mandatory motherhood’ (Fischer, 1991) or a ‘parenthood prescription’ (Veever, 1980). CONCLUDING DISCUSSION This section briefly addresses some of the gaps and limitations identified in the preceding review of literature on fertility decline. Some scholars have been critical of the limited number of variables generally used in demographic modelling, given the extensive range of economic, social, and cultural factors that could conceivably affect fertility (see Watkins 1993). In addition, the complex relationship between factors means identifying their relative impact can be extremely difficult. Various factors might be associated, however the causal relationship between these is also often a matter of interpretation. Thus, increasing female employment and changes in the status of women may be both ‘cause and effect’ (Hakim, 2003), as can the association of early childbearing with educational disadvantage and unstable partnership (Joshi and Wright, 2004). While poorer women have children earlier, it is not clear whether poverty causes high fertility or vice versa (Dixon and Margo, 2006). Using longitudinal survey data can elucidate causality in term of timing of 26 Recent sociological works similarly address changing parental identity as a factor in fertility decline (see. Lucas 2003; MacInnes 2003, 2005). 19 events, however cannot capture ‘indirect’ effects such as attitudinal change brought about by education for example. An important issue is the way in which gender is utilised in the literature. On occasion this is conflated with sex and presented as a fixed attribute of individuals, rather than one aspect of identity that is, crucially, relational. Several authors have drawn attention to the problematic consideration of gender in demography (eg Watkins 1993, Biddlecom and Greene 2000), however the limitations identified also apply to some sociological work. The focus of many studies on women has been noted above; while this may be for pragmatic reasons to do with reliability of data on births, this emphasis can reinforce a view of women as primarily reproductive. In addition, this fails to address the way in which preferences and decision-making around parenthood may be negotiated at the level of the couple. In some studies there is insufficient attention paid to the influence of gender, for example MacInnes (2003, 2005),in arguing that parental identity is undergoing change, downplays continuing differences in the practices undertaken by mothers and fathers. As mentioned above, arguments about part-time work as a means of reconciling employment and care do not address adequately women’s enduring responsibilities for care, despite wider changes in education and employment. The association of egalitarian attitudes towards gender roles with fertility intentions (Houseknecht 1987, Berrington 2004) indicate the importance of research considering gender inequalities in both the private and public sphere. As stated above, there has been much attention to explanations of fertility decline in terms of broad theories such as the Second Demographic Transition and Individualisation theses, arguing that wider macro-level changes have meant an increase in choice and values such as personal autonomy. Shifts in values and motivations however cannot be simply ‘read off’ from statistics on demographic change. While such theories imply that individual choices and preferences are to some extent an outcome of wider societal changes, the rather broad sweep character of much of this literature means there is a failure in adequately considering the iterative relationship between individual preferences and the particular social and historic context in which these are shaped. It is also important to consider the subjective meanings ascribed by actors to those choices in order to better understand motivations of behaviour: practices are culturally specific and cannot be fully understood without reference to the meanings people attribute to them. Demographic studies such as those outlined above, often based on analysis of large scale surveys are necessary to provide 20 information on what is going on in relation to fertility decline, however is not sufficient to understand why this is occurring. Comparative aggregate data at the national level for example can provide information on aspects such as ‘regime clusters’ which may relate to institutional variations. However these data are unable to address fertility motivations and expectations. As such, this supports previous calls for research which incorporates a focus on the social mechanisms of demographic phenomena that are not amenable to survey measurement (see e.g. Greenhalgh 1990) as well as on individual actors and their own goals (see e.g. Mason and Jensen, 1995). This raises issues of the epistemological and ontological assumptions underlying much research on fertility decline. Riley and McCarthy claim that no field has had more influence on demography than economics (2003: 85), and certainly much of the literature assumes this discipline’s central tenet of reasoned action and conception of individuals as rational, knowledgeable decision-makers. This is also evident in sociological work, for example preference theory, which relates individual behaviour to the wider social context in so far as this enables or constrains innate preferences. Such tenets are challenged by postmodern theoretical scholarship arguing that subjectivities are socially constituted, fluid and open to change, a conception that draws attention to the need to focus on particular historical and social contexts (see Irwin 2000, 2005). These conceptions question assumptions that there is an unproblematic relationship between what people say and what they think or do, illustrated in debates about the discrepancies between stated fertility intentions and actual behaviour. As noted above, some interpret this ‘baby gap’ as demonstrating an unmet fertility need and a lack of support to enable desired children (e.g. McDonald 2000a, Dixon and Margo 2006). Others view this as indicative more of the somewhat problematic status of attitudes (e.g. Simons 1978) or as failing to give adequate consideration to the way in which these may be impacted by competing preferences and/or subsequent life events (Smallwood and Jeffries, 2003:23). In contrast, an interpretavist account would consider such statements in part as a particular construction of identity. To illustrate, whereas several studies interviewing childless women note their emphasis on freedom, rather than assuming this reflects a literal truth and concluding that childless women prioritise autonomy, such statements may be interpreted as retrospective rationalisation and/or a defensive strategy designed to rebut potentially stigmatising subject positioning. These theoretical perspectives highlight the importance of considering issues of identity and changing subjectivities in order to more fully understand fertility behaviour. 21 REFERENCES: D’Addio, A. and d’Ercole, M. (2005) Trends and Determinants of Fertility Rates: The Role of Policies, Paris:OECD, available from http://www.oecd.org/document/4/0,2340,en_2649_33729_2380420_1_1_1_1,00.html Bagavos, C. and Martin, C. (2000) ‘Low fertility, families, and public policies’, synthesis report of the annual seminar, The European Observatory on the Social Situation, Demography and Family, Seville, 15 to 16 September Bauman, Z. 2000. Liquid modernity. Polity Press, Cambridge. Beck, U. 1992. Risk society. Towards a new modernity. Sage Publications, London. Beck, U. 1999. World Risk Society, Malden, Mass : Polity Press Beck, U. and Beck-Gernsheim, E. (1995) The Normal Chaos of Love, Oxford: Polity Press Beck, U. and Beck-Gernsheim, E. (2001) Individualization : institutionalized individualism and its social and political consequences, London: Sage Becker, G. 1991. A Treatise on the Family. Harvard University Press, Cambridge. Bernhardt, E. 1988. “The choice of part-time work among Swedish one-child mothers”. European Journal of Population 4 (2): 117-144. Berrington, A. (2003) Change and Continuity in Family Formation among Young Adults in Britain, SSRC Working Paper A03/04, University of Southampton. Berrington, A. (2004) ‘Perpetual Postponers? Women, Men’s and Couple’s fertility Intentiona and Subsequent Fertility Behaviour’, Population Trends 117, Autumn. Biddlecom, A. and Greene, M. (2000) “Absent and Problematic men: Demographic Accounts of Male Reproductive Roles”, Population and Development Review 26(1), March 2000, pp:81-115 Billari, F. C. (2004) Choices, Opportunities and Constraints of Partnership, Childbearing and Parenting: the patterns of the 1990s Billari, Francesco C. and Hans-Peter Kohler. 2004. “Patterns of low and lowest-low fertility in Europe,” Population Studies 58(2). Blossfeld, H.-P. 1995. “Changes in the process of family formation and women’s growing economic independence: A comparison of nine countries”. In Blossfeld (ed.) The new role of women. Family formation in modern societies. Westview Press, Boulder, pp. 3-32. Bongaarts, J. (2001) ‘Fertility and Reproductive Preferences in Post-Transitional Societies’. Population and Development Review, 27, pp.260-281. 22 Bouwens, A., G. Beets, and J. Schippers. 1996. “Societal causes and effects of delayed parenthood: preliminary evidence from the Netherlands”. Report written on behalf of the Commission of European Union. Brewster, K. L. and R. R. Rindfuss. 2000. “Fertility and women's Employment in Industrialize d Nations, Annual Review of Sociology, 26, 271-96. Bynner, J., Ferri, E. and Shepherd, P. (eds.) 1997. Twenty-something in the 1990s : getting on, getting by, getting nowhere, Aldershot: Ashgate Cameron, J. 1997 Without Issue: New Zealanders who choose not to have children, Christchurch, N.Z: Canterbury University Press Campbell, E. 1985 The childless marriage : an exploratory study of couples who do not want children, London: Tavistock Castles, F. (2003) ‘The World Turned Upside Down: Below Replacement Fertility, Changing Preferences and Family-Friendly Public Policy in 21 OECD Countries’, Journal of European Social Policy, Vol. 13, No. 3, 209-227 Chesnais, J.-C. 1996. ‘Fertility, family and social policy in contemporary Western Europe’, Population and Development Review 22(4):729-739. Chesnais, J.-C. 2000. “Determinants of below-replacement fertility”. In.: Below replacement fertility. Population Bulletin of the United Nations, Special Issue Nos. 40-41: 126-136, UN, New York. Chesnais, J.-C. 2001. “Comment: A march toward population recession”. In.: R. A. Bulatao and J. B. Casterline (eds.) Global Fertility Transition, supplement to Population and Development Review 27: 255–259. Coale, A. and Watkins, S. C. (eds.) 1986. The decline of fertility in Europe : the revised proceedings of a Conference on the Princeton European Fertility Project, Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press De Cooman, E., J. Ermisch, and H. Joshi. 1987. “The next birth and the labour market: A dynamic model of births in England and Wales”. Population Studies 41 (2): 237-268. Del Boca, D. 2002. “The effect of child care and part time opportunities on participation and fertility in Italy”. Journal of Population Economics 15: 549-573. Dixon, M. and Margo, J. 2006. Population Politics, IPPR: London Ekert-Jaffe, O, H Joshi, K Lynch, R Mougin, M S Rendall. Fertility, timing of births and socio-economic status in France and Britain: social policies and occupational polarisation. Population-E 2002; 3: 475-508. Esping-Andersen, G. 1999. Social foundations of postindustrial economies. Oxford University Press, Oxford. 23 European Commission (2006a) Eurostat Total Fertility Rate Indicators, http://epp.eurostat.cec.eu.int/portal/page?_pageid=1996,39140985&_dad=portal&_schema =PORTAL&screen=detailref&language=en&product=sdi_as&root=sdi_as/sdi_as/sdi_as_d em/sdi_as1210, downloaded from website on 14th April 2006. European Commission (2006b) Eurostat Indicators, Live Births outside Marriage, http://epp.eurostat.cec.eu.int/portal/page?_pageid=1996,39140985&_dad=portal&_schema =PORTAL&screen=detailref&language=en&product=Yearlies_new_population&root=Yea rlies_new_population/C/C1/C12/cab13584, downloaded from website on 22nd May 2006. Ferri, E. , Bynner, J. and Wadsworth, M. (eds.) 2003. Changing Britain, changing lives: three generations at the turn of the century, London : Institute of Education, University of London Fisher, B. (1991) ‘Affirming Social Value: Women Without Children’, in Maines, D. R. (ed.), Social organization and social process: essays in honour of Anselm Strauss, New York: A. de Gruyter. Folbre, N. 1994 Who Pays For The Kids?: Gender And The Structures Of Constraint, London: Routledge Frejka, T. 2004. “The ‘curiously high’ fertility of the USA”. Population Studies 58 (1), pp. 88-92. Gauthier, A. H. 1996. The state and the family. A comparative analysis of family policies in industrialized countries. Clarendon Press, Oxford. Giddens, A. 1992. The transformation of intimacy. Sexuality, love & eroticism in modern societies. Polity Press, Cambridge. Gillespie, R. (2001) ‘Contextualising Voluntary Childlessness Within A Postmodern Model Of Reproduction: Implications For Health And Social Needs’, Critical Social Policy, Vol. 21(2), pp. 139 – 159. Goldscheider, F. K. and Waite, L. J. (1991) New families, no families? : the transformation of the American home, Berkeley ; Oxford : University of California Press Goldscheider, F. K. and G. Kaufman. 1996. “Fertility and commitment. Bringing men back in”. In.: J. B. Casterline, R. D. Lee, and K. A. Foote (eds.) Fertility in the United States. New patterns, new theories. Supplement to Population and Development Review 22, Population Council, New York, pp. 87-99. Graham, E. and Boyle, P. (2003) ‘Low Fertility in Scotland: A Wider Perspective’, chapter in Annual Review of Demographic Trends: Scotland’s Population 2002, General Registrar Office for Scotland, http://www.gro-scotland.gov.uk/statistics/library/annrep/02annualreport/index.html , dowloaded on 14th April 2006. 24 Grant, J., Hoorens, S., Sivadasan, S., van het Loo, M., DaVanzo, J., Hale, L., Gibson, S., and Butz, W. (2004) Low fertility and Population Ageing: Causes, Consequences, and Policy Options, Cambridge: RAND. Available at http://www.rand.org/pubs/monographs/MG206/index.html Greenhalgh, S. (1990) ‘Towards a political economy of fertility: anthropological contributions’, Population and Development Review, 16 (1) pp: 85-106. GROS (2005) ‘Scotland's Population 2004 - The Registrar General's Annual Review of Demographic Trends’, General Register Office for Scotland, http://www.groscotland.gov.uk Gustaffson, S.S, Kenjoh, E. adm Wetzels, C. (2002) ‘The Role of Education on Postponement of Maternity in Britain, German, the Netherlands and Sweden’, in E. Rsupini and A. Dale (eds.) The Gender Dimension of Social Change, Bristol: The Policy Press Hakim, C. 2005. Childlessness in Europe: Research Report to the Economic and Social Research Council (10/03/2005) http://www.esrcsocietytoday.ac.uk/ESRCInfoCentre/Plain_English_Summaries/LLH/lifeco urse/index498.aspx?ComponentId=9309&SourcePageId=11751 Hakim, C. 2003 'A New Approach to Explaining Fertility Patterns: Preference Theory', Population and Development Review 29 (3), pp. 349-374. Heckman, J. and J. R. Walker. 1990. “The relationship between wages and income and the timing and spacing of births: Evidence from Swedish longitudinal data”. Econometrica 58 (6): 1411-1444. Hird, M. J. and Abshoff, K. 2000. ‘Women without children: a contradiction in terms’, in Journal of Comparative Family Studies, Vol.31, 3. Hobson, B. and Olah, L. Sz. (2006a) ‘BirthStrikes?: Agency and Capabilities in the Reconciliation of Employment and Family’, Marriage and Family Review, No. 39, The Haworth Press Hobson, B. and Olah, L. Sz. (2006b), ‘The Positive Turn or BirthStrikes?: Sites of Resistance to Residual Male Breadwinner Societies and to Welfare State Restructuring’, Recherche et Previsions no.83 (March), Special Issue: Kind and Welfare State. Reforms of Family Policies in Europe and North America, CNAF Hoem, B. 1995. “Sweden”. In.: H.-P. Blossfeld (ed.) The new role of women. Family formation in modern societies. Boulder: Westview Press, pp. 35-55. Hoem, B. 2000. “Entry into motherhood in Sweden: The influence of economic factors on the rise and fall in fertility, 1986-1997”. Demographic Research 2, Article 4. Hotz, V. J., Klerman, J.A., and Willis, R. J. (1997) ‘The Economics of Fertility in Developed Countries’, in M. R. Rozenzweig and O. Stark (eds.) Handbook of Populaiton and Family Economics, Volume 1A., Amsterdam: Elsevier. 25 Houseknecht, S.K. (1987) ‘Voluntary Childlessness’ ,in Sussman, MB and Steinmetz, SK (eds) Handbook of Marriage and the Family, Plenum Press: New York Irwin, S. 2000 ‘Reproductive Regimes: Changing Relations of Interdependence and Fertility Change’, Socioogical Research Online, vol. 5, (1) Irwin, S. 2005 Reshaping Social Life, London: Routledge Jamieson, L. (1998) Intimacy: Personal Relationships In Modern Societies, Cambridge: Polity Press Joshi, H. and Wright, R. (2004) Population Replacement and the Reproduction of Disadvantage, Starting Life in the New Millennium: The Allander Series 2003/2004 Joshi, H. 1998. “The opportunity costs of childbearing: More than mother’s business”, Journal of Population Economics. Vol.11, No.2, pp.161-83. Joshi, H. 2002. “Production, Reproduction And Education: Women, Children And Work In Contemporary Britain”. Population and Development Review 28 (3): 445-474. Kemkes-Grottenhaler, A. 2003. “Postponing or rejecting parenthood? Results from a survey among female academic professionals”. Journal of Biosocial Science 35: 213-226. Kertzer, D. and Fricke, T. (eds.) 1997. Anthropological demography: toward a new synthesis , Chicago, Ill. ; London : University of Chicago Press Kiernan, K. 1989. “Who remains childless?” Journal of Biosocial Science 21: 387-398. Kiernan, K. 1997. “Becoming a young parent: A longitudinal study of associated factors”. British Journal of Sociology 48 (3): 406-428. Kiernan, K. (1998) ‘Parenthood and Family Life in the United Kingdom’, Review of Population and Social Policy, No.7, pp:63-81 Kohler, H.-P., F. C. Billari, and J. A. Ortega. 2002. “The emergence of lowest-low fertility in Europe during the 1990s”. Population and Development Review 28 (4): 641-680. Leete, R. (1998) Dynamics of values in fertility change, Oxford: Clarendon Press Lesthaeghe, R. 1995. “The second demographic transition in Western countries: An interpretation”. In.: K. O. Mason and A.-M. Jensen (eds.) Gender and family change in industrialized countries. Oxford, Clarendon Press, pp. 17-62. Lesthaeghe, R. 2001. “Postponement and recuperation: Recent fertility trends and forecasts in six Western European countries”. Paper presented at the IUSSP Seminar “International perspectives on low fertility: Trends, theories and policies”, Tokyo, 21-23 March 2001. Lesthaeghe, R. and K. Neels. 2002. “From the first to the second demographic transition: An interpretation of the spatial continuity of demographic innovation in France, Belgium and Switzerland”. European Journal of Population 18 (4): 325-360. 26 Lewis, J. (2001) ‘The decline of the male breadwinner model: the implications for work and care’, Social Politics, 8:2, 152-70. Lewis, J. 2006. Perceptions of Risk in Intimate Relationships, Journal of Social Policy, Vol. 35, 1, pp.39 - 57 Liefbroer, A. C. 1998. “Understanding the motivations behind the postponement of fertility decisions: Evidence from a panel study”. Paper presented at the workshop on “Lowest-low fertility”, Max-Planck Institute for Demographic Research, Rostock, 10-11 December 1998. Liefbroer, A. C. and M. Corijn 1999. “Who, what, where and when? Specifying the impact of educational attainment and labour force participation on family formation”. European Journal of Population 15 (1): 45-75. Lisle. L. 1999 Without Child, New York: Routledge Lucas, R. (2003) ‘Kids!Who’d Have ‘Em? New meanings of childhood an the trend towards voluntary childhood’, paper presented at the British Sociological Association Annual Conference, York, 11th – 13th April 2003 MacInnes, J. and Perez Diaz, J. (2005) ‘The Reproductive Revolution’, paper presented at 37th World Congress of the International Institute of Sociology, 5-9 July, Sweden MacInnes, J., (2003) ‘Sociology and Demography: A Promising Relationship?’, In Edinburgh Working Papers in Sociology no.23, Edinburgh University: Edinburgh Marshall, H. 1993. Not Having Children, Melbourne ; Oxford : Oxford University Press Martin, S. P. 2000. “Diverging fertility among U.S. women who delay childbearing past age 30”. Demography 37 (4): 523-533. Mason, K. and Jensen, A. M. (eds.) (1995) Gender and family Change in Industrialised Countries, Oxford: Clarendon Press McAllister, F. and Clarke, L. (1998) Choosing Childlessness, London : Family Policy Studies Centre McDonald, P. 2000a, ‘The “Toolbox” of Public Policies to Impact on fertility – a Global View’. paper presented at seminar on ‘Low fertility, families and Public Policies, organised by European Observatory on Family Matters, Sevilla, Sept15-16, 2000. McDonald, P. 2000b. ‘Gender equity in theories of fertility transition’. Population and Development Review 26 (3): 427-439. McDonald, P. 2000c. ‘Low fertility in Australia: evidence, causes and policy responses’, People and Place, 8(2):6-20 McRae, S. (ed) 1999. Changing Britain: families and households in the 1900s. Oxford : Oxford University 27 Melhuish, E.C. and Moss, P. (eds.), (1991) Daycare for Young Children: International Perspectives, London: Tavistock/Routledge Meron, M. and I. Widmer. 2002. “Unemployment leads women to postpone the birth of their first child”. Population-E 2002, 57 (2): 301-330. st Morgan, S. P., Berkowitz King, R. (2001). Why have children in the 21 century? Biological predisposition, social coercion, rational choice. European Journal of Population; 17 (1): 3-20. Murphy, M. 1992. “Economic models of fertility in post-war Britain – a conceptual and statistical re-interpretation”. Population Studies 46 (2): 235-258. Murphy, M. 1993 ‘The contraceptive pill and women’s employment as factors of fertility change in Britain 1963-1980: A challenge to conventional view’. Population Studies 47 (2): 221-243. Oláh, Livia Sz. (2005) ‘First childbearing at higher ages in Sweden and Hungary: a gender approach’, paper presented at the 15th Nordic Demographic Symposium, Aalborg University, Denmark, 28 – 30 April 200 ONS (2005a) Key Population and Vital Statistics: Local area and Health Authority Areas, Series VS No.30, Palgrave MacMillan ONS (2005b) Fertility: women are having children later, Statistics Website: archived Dec 2005, http://www.statistics.gov.uk/CCI/nugget.asp?ID=762&Pos=&ColRank=2&Rank=224, accessed 10th March 2006 ONS (2005c) Birth Statistics, Series FM1 No 33. Oppenheimer, V. K. 1994. ‘Women’s Rising Employment and the future of the family in industrialised societies’, Population and Development review, 20:2, 293-342. Pinelli, A., Hoffman-Nowotny, H. J. and Fux, B. (2001) Fertility And New Types Of Households And Family Formation In Europe, Council of Europe, Population Studies No.35. Presser, H. (2001) ‘Comment: A Gender Perspective for Understanding Low fertility in Post-transitional Societies’, Population and Development Review, Vol. 27, pp.177-183. Prioux, F. 2003. ‘Age at first union in France: A two-stage process of change’ Population-E 58 (45): 559-578 Rake, K (ed) (2000) Women's Incomes over the Lifetime. London: The Stationery Office. Rendall, M. S. 2003. “How important are intergenerational cycles of teenage motherhood in England and Wales? A comparison with France”. Population Trends 111 (Spring 2003): 2737. 28 Rendall, M. S. and S. Smallwood. 2003. “Higher qualifications, first-birth timing, and further childbearing in England and Wales”. Population Trends 111, Spring, pp: 18-26. Riley, N. and McCarthy, J. (2003) ‘Demography in the Age of the Postmodern’, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge Santow, G. and Bracher M. (1998) Traditional families and fertility decline Lessons from Australia's Southern Europeans. In: Leete R (ed.). The Dynamics of Values in Fertility Change. Oxford: Clarendon Press Santow, G. and Bracher M. (1996) ‘Whither Marriage? Trends, Correlates and Interpretations’, Stockholm Research Reports in Demography, No. 108. Simons J (1978) Illusions about Attitudes, in Population Decline in Europe, Council of Europe, Strasbourg, London: Edwin Arnold Smallwood, S. and Jeffries, J. (2003) ‘Family Building Intentions in England and Wales: trends, outcomes and interpretations’, Population Trends No 112, Summer Smallwood, S. (2002) ‘New Estimates of Trends in Births by Birth Order in England and Wales’, Population Trends No 108, Summer. Sobotka, T. 2004. Postponement of Childbearing and Low Fertility in Europe, PhD thesis, University of Groningen. Dutch University Press, Amsterdam, 298 pp. Taylor-Gooby, P. (ed) 2004. New risks, new welfare: the transformation of the European welfare state, Oxford : Oxford University Press Van de Kaa, D. J. (1987). ‘Europe’s second demographic transition’, Population Bulletin 42 (1). Van de Kaa, D. J. (1994) ‘The second demographic transition revisited: Theories and expectations’, in Beets et al. (eds.) Population and family in the Low Countries 1993: Late fertility and other current issues. NIDI/CBGS Publication, No. 30, Swets and Zeitlinger, Berwyn, Pennsylvania/Amsterdam, pp. 81-126. Van de Kaa, D. J. 2004. “The true commonality: In reflexive societies fertility is a derivative”. Population Studies 58 (1): 77-80. Van Nimwegen, N., M. Blommesteijn, H. Moors, and G. Beets. 2002. “Late motherhood in the Netherlands: Current trends, attitudes and policies”. Genus 28 (2): 9-34. Veevers, J. E. (1980) Childless by choice, Toronto: Butterworths Wasoff, F. and Carty, A. 2004. A Sociological Literature Review Of Voluntary Childlessness in the EU, part of a demographic review for an EU funded study led by the Centre d'Estudis Demogràfics [CED], Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. Watkins, S. C. (1993) ‘If All We Knew About Women Was What We Read In Demogrpahy, What Would We Know?’ Demography, 30 (4) Pp.551-577. 29 APPENDIX 1: Total Fertility Rates, European Union 1994 - 2004* 1994 2004 Low Fertility (Classifications refer to 2004) Turkey N/A 2.20 (e) Iceland 2.14 2.03 Ireland 1.85 1.99 (e) France 1.66 1.90 (p) Finland 1.85 1.80 Norway 1.86 1.81 Denmark 1.81 1.78 Sweden 1.88 1.75 Netherlands 1.57 1.73 United Kingdom 1.74 1.74 (e) Luxembourg 1.72 1.70 Belgium 1.56 1.64 (e) Very Low Fertility Cyprus 2.23 1.49 (p) Austria 1.47 1.42 Portugal 1.44 1.42 (e) Estonia 1.37 1.40 (e) Malta 1.89 1.37 Germany 1.24 1.37 (e) Croatia 1.52 1.35 Italy 1.21 1.33 Spain 1.21 1.32 (e) Lowest Low Fertility Greece 1.35 1.29 (e) Romania 1.42 1.29 Bulgaria 1.37 1.29 Hungary 1.65 1.28 Lithuania 1.57 1.26 Slovakia 1.66 1.25 Latvia 1.39 1.24 Czech Republic 1.44 1.23 Poland 1.80 1.23 Slovenia 1.32 1.22 (e) Source: European Commission (2006) Eurostat Indicators * Latest year for which figures available (e) estimated value (p) provisional value 30 APPENDIX 2: Britain Charts Illustrating Changes Over Time In Childbearing In Completed Family Size for Selected Birth Cohorts England and Wales 25 Percentage 20 15 10 5 0 1920 1940 1945 1950 1955 1959 Birth Cohorts No Children One child Four or more Source: ONS Birth Statistics 2004, Series FMl No 33, Tables 10.2 and 10.5 * Includes births at ages over 45 Fertility Rates by Age of Mother: 1971 - 2003 LiveB irths per 1,000 women 180 160 1971 140 1981 120 1991 100 2001 80 2003 60 40 20 0 Under 20 20–24 25–29 30–34 35–39 40–44 Source: Social Trends 35, ONS 2005 31