RegulatoryAnalysisAttachment2007-01082

advertisement

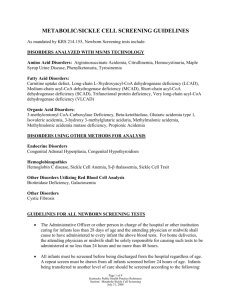

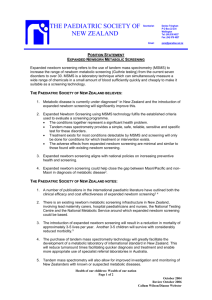

REGULATORY ANALYSIS FOR AMENDMENTS TO THE STATE OF COLORADO NEWBORN SCREENING REGULATIONS 5 CCR 1005-4 Section 1.6, List of Conditions for Newborn Screening Adopted by the State Board of Health on November 28, 2007 Section 25-4-1004, C.R.S. The nature of the revisions is summarized in the accompanying Statement of Basis and Purpose and Specific Statutory Authority. Seven regulatory analysis elements follow: 1. A description of the classes of persons who will bear the costs and/or benefits from the rule. Colorado parents, their newborns, and their insurers, including Medicaid, will bear the costs and derive the benefits of the rule change. 2. The probable quantitative and qualitative impacts of the rule, economic and otherwise, upon the affected classes. Quantitative: An estimated additional 1-3 newborns with significant treatable metabolic defects will be discovered annually allowing for the initiation of medical measures appropriate to the disorder identified. Qualitative: Parents of these newborns will be relieved of the burden of the extensive diagnostic burden to determine the cause of the metabolic anomalies that typically accompany these disorders. The Colorado Newborn Screening program will be recognized as meeting or exceeding the standard of care for screening as to the number and severity of disorders. 3. Probable costs to the Department and to local health departments and anticipated effects on state revenues. No additional fee increase will be necessary to accomplish this improvement. 4. A comparison of the probable costs and benefits of the rule and probable costs and benefits of inaction. Since the implementation of MS-MS screening on July 1, 2006, twenty-one (21) cases of significant metabolic illness have been detected in Colorado Newborns ( or ca.1:3250) 1 using this technology—compared to an original estimate of 17-20 children per year. The technology has fulfilled all expectations for the detection of these metabolic disorders, including the detection of one case of a disorder that is currently not included in the list of first newborn screen disorders. 5. A determination of whether there are less costly or less intrusive means to achieve the purpose of the rule. No alternative is available at the present time. Private sector costs for screening alone range from $20-25 per specimen 6. A description of alternative methods for achieving the purpose of the rule. No alternative is available at the present time. MS/MS technology is a rapidly changing technology, with greater capabilities anticipated over time. The capability of MS/MS technology provides for screening and detection of a number of fatty acid oxidation, amino acid and organic acid disorders, that is anticipated to continue to increase over time as the technology further develops. The four disorders proposed for addition meet the criteria required by C.R.S. § 25-41004(1)(c): (I) The condition for which the test is designed presents a significant danger to the health of the infant of his family and is amenable to treatment; (II) The incidence of the condition is sufficiently high to warrant screening; (III) The test meets commonly accepted clinical standards of reliability, as demonstrated through research or use in another state or jurisdiction; and (IV) The cost-benefit consequences of screening are acceptable within the context of the total newborn screening program. 7. To the extent practicable, a quantification of the data used in the analysis, taking into account both short-term and long-term consequences. The estimates noted below are based largely on the most common of the newly detectable diseases, for which there is precise outcome data on a large series of patients (Medium chain acyl CoA Dehydrogenase deficiency, or MCAD. Of the 21 newly identified cases, eight were identified as MCAD cases and are subject to serious impairment.2,4 The yearly cost estimate of such impairment has been estimated as $135,000/year cost in 1996 dollars for individuals with severe cerebral palsy.5 Twelve percent of the patients with MCAD in Iafolla’s study6, had extreme outcomes such as severe cerebral palsy and global developmental delay, and a greater proportion of such outcomes would be expected in other of the disorders detected by MS/MS (Janet Thomas, Inherited Metabolic Diseases Clinic, The Children’s Hospital, Denver). This figure would be $166,000 in today’s dollars using a conservative yearly change in the Consumer Price 2 Index (CPI). This translates to $1,326,000 saved for the 8 seriously damaged infants detected during FY07 by MS-MS screening methods currently in use. Inflation could easily result in an adjustment of 7-15% per year. At this point it is not possible to extrapolate the cost savings for MCAD cases to the four disorders for which approval to add to 5 CCR 1005-4 Part 1.6 is requested. However, the accumulating evidence is that medical interventions are only possible if the metabolic disorder is definitely identified. 1 Sweetman L. Newborn screening by Tandem Mass Spectrometry: Gaining Experience. Clinical Chemistry 2001;47:1937-8. 1 Pollitt RJ et al. Neonatal screening for inborn errors of metabolism: Cost, yield and outcome. Health Technology Assessment 1997;1:1-162. 3 Viscusi WK. The value of risks to life and health. Journal of Economic Literature 1966;31:1912-46. 4. Schoen EJ et al. Cost-benefit analysis of tandem mass spectrometry for newborn screening. Pediatrics 2002;110:781-6. 5. Insinga RP et al. Newborn screening with tandem mass spectrometry: Examining its costeffectiveness in the Wisconsin newborn screening panel. J Pediatr 2002;141:524-31. 6. Waitzman NJ et al. The cost of birth defects: Estimates of the value of prevention. University Press of America, Lanham 1996. 7. Iafolla Ak et al. Medium-chain acyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase deficiency: Clinical course in 120 affected children. Journal of Pediatrics 1994;124:409-15. 8 Boles RG et al. Retrospective biochemical screening of fatty acid oxidation disorders in postmortem livers of 418 cases of sudden death in the first year of life. Journal of Pediatrics 1998;132:924-33. 9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Contribution of selected metabolic diseases to early childhood deaths – Virginia, 1996 – 2001. MMWR 2003;52:677-9. 3