WHAT IS A BARD - Ansteorran Bardic Guild

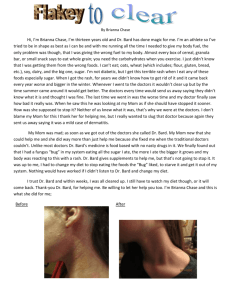

advertisement

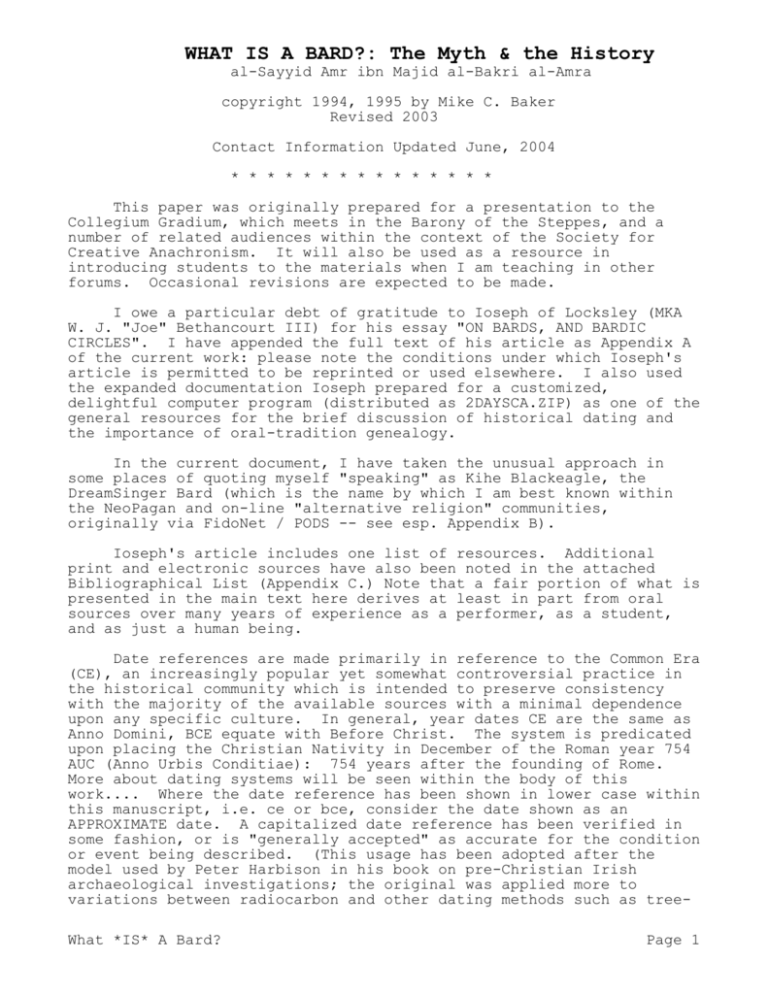

WHAT IS A BARD?: The Myth & the History

al-Sayyid Amr ibn Majid al-Bakri al-Amra

copyright 1994, 1995 by Mike C. Baker

Revised 2003

Contact Information Updated June, 2004

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

This paper was originally prepared for a presentation to the

Collegium Gradium, which meets in the Barony of the Steppes, and a

number of related audiences within the context of the Society for

Creative Anachronism. It will also be used as a resource in

introducing students to the materials when I am teaching in other

forums. Occasional revisions are expected to be made.

I owe a particular debt of gratitude to Ioseph of Locksley (MKA

W. J. "Joe" Bethancourt III) for his essay "ON BARDS, AND BARDIC

CIRCLES". I have appended the full text of his article as Appendix A

of the current work: please note the conditions under which Ioseph's

article is permitted to be reprinted or used elsewhere. I also used

the expanded documentation Ioseph prepared for a customized,

delightful computer program (distributed as 2DAYSCA.ZIP) as one of the

general resources for the brief discussion of historical dating and

the importance of oral-tradition genealogy.

In the current document, I have taken the unusual approach in

some places of quoting myself "speaking" as Kihe Blackeagle, the

DreamSinger Bard (which is the name by which I am best known within

the NeoPagan and on-line "alternative religion" communities,

originally via FidoNet / PODS -- see esp. Appendix B).

Ioseph's article includes one list of resources. Additional

print and electronic sources have also been noted in the attached

Bibliographical List (Appendix C.) Note that a fair portion of what is

presented in the main text here derives at least in part from oral

sources over many years of experience as a performer, as a student,

and as just a human being.

Date references are made primarily in reference to the Common Era

(CE), an increasingly popular yet somewhat controversial practice in

the historical community which is intended to preserve consistency

with the majority of the available sources with a minimal dependence

upon any specific culture. In general, year dates CE are the same as

Anno Domini, BCE equate with Before Christ. The system is predicated

upon placing the Christian Nativity in December of the Roman year 754

AUC (Anno Urbis Conditiae): 754 years after the founding of Rome.

More about dating systems will be seen within the body of this

work.... Where the date reference has been shown in lower case within

this manuscript, i.e. ce or bce, consider the date shown as an

APPROXIMATE date. A capitalized date reference has been verified in

some fashion, or is "generally accepted" as accurate for the condition

or event being described. (This usage has been adopted after the

model used by Peter Harbison in his book on pre-Christian Irish

archaeological investigations; the original was applied more to

variations between radiocarbon and other dating methods such as treeWhat *IS* A Bard?

Page 1

ring comparison within the archaeological community, but hopefully the

parallels to oral history and tradition are somewhat obvious....)

This document may be used in periodicals and other publications

of the SCA and its various branches without monetary cost. I do

request a copy of any publication where it might appear. I reserve

the right of withdrawing this permission at a future time.

In Service to the Ideals of the Society,

referred to often as "the Dream",

Amr ibn Majid al-Bakri al-Amra (formerly Amra M'Chib Bakerian)

House Dreamwind of the Shadowed Moon,

c/o Mike C. Baker

109 Sunset DR

Plano TX 75094

Cel (214) 402-8243

Email: KiheBard@hotmail.com

OR kihe@rocketmail.com

OR MCBaker216@cs.com

What *IS* A Bard?

Page 2

WHAT *IS* A BARD?: The Myth & the History

The word "bard" has been used in a great many ways throughout

history. Unfortunately for the purpose of the current discussion,

most such references are inaccurate, inappropriate, and / or just

plain wrong -- at the same time that they may be "right" for the

person speaking or writing. Among other issues, it is important to

consider the time-frame of the "voice" speaking, the culture from

which they come, and the origins of the person being spoken of. The

inexactitudes of English and other modern languages are further

compounded when even well-learn'd scholars have been known to muddy

the issue through loose applications of the term "bard". (Modern

authors are noted for their tendency to the reductio, often to the

point of in absurdio, in other matters -- why not in this as well?)

The equation of bard equal poet is often made, and is supportable

in certain specific contexts. The inverse, poet equal bard, can not

always be said to apply. The Welsh formalities, and the tightly

controlled style so lovingly summarized and portrayed by Robin of

Gilwell (Jay Rudin) within the structures of the same {1}, are the

strongest example I am familiar with. And even those strictures may

tend to confuse matters more thoroughly than they might explain them

(every Welsh bard after a certain point in time had to have composed

in each of twenty-four schemes to be accorded the title of bard, but

the term in general still transliterates as "poet").

Some authors within "modern" times make this verbal distinction

between bard and poet differently: Robert Graves (in his influential

work The White Goddess) distinguishes between Muse-poets, inspired by

"the Goddess" as personally experienced, and Apollonian poets,

praising the patriarchal kingdoms and related institutions. Geoffrey

Ashe (The Discovery of King Arthur) uses "bard" more loosely, but

echoes an important related theme:

The Druids were a close-knit, highly trained religious order, an

immensely influential elite. They were priests, scholars, bards,

royal counselors, and seers. They flourished in Ireland and Gaul

as well, but their advanced colleges were in Britain. {2}

Historical Variations & Terminologies

Professional storytellers among the ancient Greeks were called

_rhapsodes_, and were organized into at least loose organizations.

(One such band were in fact known as the Homeridae.) How often are we

subjected to characterizations of Homer himself as a bard, even when

later Greeks strove mightily to discredit the poets for their

departures from the rational (what we might call "the scientific")?

Who in the modern world would NOT accord Homer such a rank and title?

Poets and folk who were most likely "true" bards are found many places

throughout the surviving Greek and Roman sources. In the Odyssey, we

are told of at least two bards and a herald: Phemius, Demodocus, &

Medon. Orpheus, that great lyre-player of mythic fame who has been

advanced to the rank of demi-god by several "classical" sources, was

1

"The Four-and-Twenty", Black Star A&S issue, A.S.XXVII

2

_The Discovery of King Arthur_, pg. 27

What *IS* A Bard?

Page 3

noted as "a musician of such power and sweetness that even the wild

creatures would gather to listen to him".

Patrons of the bardic arts among the ancient "Classical" nonChristian deities included Dionysus, Apollo, the Muses {3}, Pan, the

Graces, Liber, and the old centaur Chiron. Indeed, special note

should be made of Chiron, considered "the source of the arts of

healing and music". At least one modern observer has made the

connection between this figure and the tribal traditions of horsenomad "medicine-men" or shamans among the ancestors of the Greek

culture (some one of the successive waves of invasion which served to

mold the Pelasgian [sea-people], Achaean, Argive, Doric, Ionian,

Mycenaean, and other Graician civilizations) {4}.

Non-GrecoRoman deities and related mythological figures which are

associated with bards, or poets, or similar professionals such as the

skalds and saga-men, include: (Norse / Germanic) Baldr, Suttung,

Odin/Wotan/Woden, Kvasir, Loki, Mimir, Hoenir; (Celtic) Brigid, Lugh,

Bran, Math, Ecne, and others; Coyote in the tribal lore of the

American Southwest is very recognizably a storytelling inspiration AND

patron; among the Botocudo of the Brazilian mountains "The master of

spirits was 'Father Whitehead', the owner of songs and lord of the

rain and the storm".

Lucan, a Latin author of the 5th century (449ce) {5}, used the

term "Bardi" in reference to the national poets & musicians of both

Gaul and Britain. In fact, among the old Gaelic / Celtic tribal

clans, each chieftain had a household bard. Even into the 18th

century CE, the house-bard sang the lineage and deeds of the clan IN

IRISH, or at the very least what we now call Gaelic, among the

Highlanders of Scotland. It has been observed by several sources that

"The most influential and conservative element of Celtic society was

that of the bards." {6}

In the redoubtable _Oxford English Dictionary_, on "pg. 667" of

the Compact Edition, we find reinforcement for the basic view of the

bard-as-poet/musician as already presented here, and also intimation

of his association with prophetic ability. The word "BARD" is derived

variously from Gaelic, Irish, Welsh, and Latin, in addition to Old

The separate fields of inspiration for each Muse are a Roman

invention. The Romans enumerate the Nine and assign their charges

as: Calliope (epic poetry), Clio (History), Euterpe (flute

playing), Erato (lyric poetry & hymns), Terpsichore (dance),

Melpomene (tragedy), Thalia (comedy), Polyhymnia (mime), and

Urania (astronomy, or more anciently astrology).

They are thought by the Greeks to be daughters of Zeus and

Mnemosyne (memory).

3

Note that "Greek" is a name imposed by the later Roman

conquerors, derived from "Graicia".

4

In this paper, where a date qualifier is used and is shown

in lowercase, that date is only an approximation. Uppercase

indicates a "solid", documentable and verifiable date citation.

5

6

Nikolai Tolstoy, _The Quest for Merlin_, (c) 1985

What *IS* A Bard?

Page 4

Celtic (this last may be referred to in some other sources as

"Goi(d)delic" [?]). Definition One from the OED reads:

An ancient Celtic order of minstrel-poets, whose primary function

appears to have been to compose and sing (usually to the harp)

verses celebrating the achievements of chiefs and warriors, and

who committed to verse historical and traditional facts,

religious precepts, laws, genealogies, etc. Still the word for

"poet" in modern Celtic languages; and in Welsh _spec_: A poet or

versifier who has been recognized at the Eisteddfod.

Quoted from the sources cited in the OED as supporting this

definition:

from Powel writing in 1584CE _Lloyd's Cambria_ pg. 15: "This word

_Bardh_ signified such as had knowledge of things to come."

Shakespeare, _Richard III_, 4th Act: "A bard of Ireland told me

once, I should not live long after I saw Richmond."

The entry for "bard" in the OED also supports the view of the gleeman

as being the equal of both bard and scald.

Bards in Historical Celtic Society

There were definite cultural differences in the expectations

associated with the station of bards even within the longest-surviving

"pure Gaelic" civilizations. Welsh & Irish bards both developed into

distinct classes, with subtly differing yet well-defined views as to

the hereditary and other aspects of the transmission and accordance of

rights, responsibilities, and privileges granted to or reserved by the

recognized bards. Among the Welsh, the formal laws governing bards

are recorded as having been first codified / regularized by Howel Dda

and later substantially revised by Gruffyd ap Conan. {7} The Welsh are

also thought of as those primarily responsible for the concept of the

Eisteddfod, although it should be noted that the Irish training system

of twelve year's study culminating in the award of the title OLLAVE

was in its fashion much more rigorous. We will return to this

distinction shortly.

Within the SCA, we seem to think most often of the capital-B Bard

as found and defined within the Celtic, Gaelic-speaking, cultures.

There are at least related positions found in most so-called

"primitive" peoples. The shaman, "witch doctor", or "medicine man"

may or may not fill many of the same functions as the Celtic bard.

More than entertainer, the "true" bard was (and is) also an educator.

It was (and is) completely within his power to make or destroy

reputations -- and thereby whole lives. The concept of the bardic

"right of satire" is dealt with in more depth elsewhere in this study.

Even given his traditional protections, the bard was not always

In at least one notable case, this was because of apparent

safe.

It _should_ be noted that King Gruffyd was educated in

Ireland and may in fact have been making revisions intended to

either bring the practices of the Welsh college more into line

with what he had experienced, or (and this is certainly the less

likely premise) to have been attempting to avoid perceived

pitfalls of the Irish system. Failing written documentation of the

actual details of the structure of training and recognition in

Ireland, no reliable decision can be made.

7

What *IS* A Bard?

Page 5

vainglory: Taillefu, personal bard to William the Conqueror, became

famous not only for advancing into England from the beach while

juggling his sword and singing the tales of Charlemagne or Roland, but

also for being the first man killed at the Battle of Hastings. He had

previously begged for the privilege of being allowed to strike the

first blow... {8}

Cultural and Other Possible Bardic Equivalents

Other titular names which might be considered substantially

similar to "bard" in the European cultures with which we have the best

familiarity are the Norse "scop" (for the Anglo-Saxon, residents in

the hall of an *atheling*, or petty king), perhaps the jongleur

(France) and gaukler (in the Germanies); maybe the generally noble

troubadour (southern France, northern Spain, northern Italy) & the

trouve're (northern and central France, plus some penetration into

Norman England: poets similar to the troubadours); the Minnesingers of

Germany (associated also with the troubadour tradition, and

forerunners of the Meistersinger) *maybe* the ioculator (although this

is more often associated with a type of jester?), et cetera.

It has been observed by at least one student of Jewish rabbinical

history that the rabbi was, from the most ancient times, very much

similar to the bard as well: above all other things, bards and rabbis

are both teachers, both use parable and allegory, and both professions

use music as a method of presenting their teachings.

Frank Muir, writing in the last quarter of the 20th century CE,

notes that:

A certain amount of class distinction entered into music

during the Middle Ages. The Roman name for a professional

musician was JOCULATOR; this became "juggler" in English and was

the word used to describe the practitioners at the bottom end of

the entertainment world, the conjurers, acrobats, bear-leaders

and actors as well as the fiddlers. {9}

[Sources used in preparing this study disagree whether the

following related tidbit applies more probably to the troubadour or

the trouve`re: tunes used with their poems are believed by some to

have been written primarily by jongleurs, or possibly apprentices /

servants called "joglar", although the poetic words associated were

typically very much -- sometimes quite jealously! -- the troubadour's

own.]

Some more-specific bardic appellations within Celtic regions

include the filidh (seer: see Ioseph's article for the relation

between this and the word "druid"); ollave (master poet); and the

Gogynfeirdd or Prydydd (types of Welsh "Court Poets"). For all that

oral and recorded histories do not always agree, the names of some of

the most famous Celtic bards survive: Taliesin, Amergin mac Miled

(also accorded the place of first Druid in Ireland), Myrddin (who is

often equated with Merlin), Tuan mac Carell, Craftiny, etc. One Welsh

8

Muir, pg. 17, as well as other sources

pp 16-17, _An Irreverent and Thoroughly Incomplete Social

History of Almost Everything_, (c) 1976

9

What *IS* A Bard?

Page 6

source quotes a "prime bard of the Cymry" named Taliesin as saying

"Iddno and Heinin called me Merddin". Another source claims that

there were three class divisions of "bards among the Druids": Fe-Laoi

(Hymnists), Senachies (epic singers & historians), and Fer-Dan (the

more musical and secular wandering entertainers AND satirists). {10}

"Fellow-Travelers": Entertainment Specialists

Positions and titles which it is often believed would *not*

usually have been considered TRUE bards within at least the earlier

portion of the SCA "period" (600ce to 1600/1650ce) include: minstrel

or "menestriers" (see following paragraph for a dissenting view {11});

gleeman {12}, musician (or specific instrumentalist type such as the

harpist, piper, lutanists, or the trumpeteer), juggler, "ystriones"

(actors), "waits" (town pipers or bandsmen, after a fashion), goliards

(minor ecclesiaticals and students: "Their writings were often frothy,

sometimes obscene; their conduct was in accordance." {13}) and also

vagantes ("wanderers" related to the goliard); harlequins, and other

"players", etc.

Dissension Among the Experts

For some feel of just how greatly modern authorities differ in

reference to the terminology, I will note in passing that under the

listing for "minstrel" in the _Encyclopedia Britannica_, c. 1960ce,

are also listed many of the equivalents we generally account "true

bards". Minstrel derives from the same Latin roots as minister, which

originally meant particularly and specifically "servant". A minstrel,

by my own derivation, is therefore one who serves through music. {14}

pg. 81, W. Winwood Reade _The Veil of Isis, or Mysteries of

the Druids_, Newcastle Publishing reprint, 1992

10

consider also the last lines of, if not the full text of,

"So you wish to be a bard" by Rathflaed DuToutNoir, the Black Bard

of Meridies [mka Stephen R. Melvin], attached here as Appendix D

{PERMISSION FOR WIDER PUBLICATION PENDING}

11

Some sources make the title of gleeman out to be actually

wandering scops, not attached to a single patron, which would

return them to the company of "true bards" and equivalents.

12

Gustave Reese _Music in the Middle Ages_ (c) 1940. Chapter

7, "Secular Monody". The goliards primarily wrote songs in Latin.

As a group, their influence declined in the first half of the 13th

century, with the rise of the great permanent universities and the

growth of residential student life. In some ways, the "Animal

House" image of college fraternity life is a descendant of the

goliard life-style.

The mythical patron of the goliards was the "Bishop Golias".

Their disreputable conduct and satires against the Church led to

the denial of clergy privilege in the end. Goliards are considered

the primary source of most of that body of work we know today as

"Carmina burana".

13

Reese notes: "After the Norman Conquest, gleeman and scop

gave place to minstrels (the name changing more than the

function), both resident in the court of the feudal lord and

travelling on the highways." Chapter Eight.

14

What *IS* A Bard?

Page 7

Minstrel guilds date back to at least 1105ce at Arras, 1321ce Paris,

and 1469ce London (the London guild survives even today, as the

Corporation of Musicians of London). At least one guild (at Beverly)

restricted membership to those of "position" or of proven worth

(either through demonstrated skill or proof of employment by a noble

household).

In the late 15th century, at least according to _Britannica_, the

introduction of printing led to an increasing emphasis upon

instrumental performance by minstrels and a related decline in the

oral tradition. The "wandering minstrel" as a recognized type dates

generally to earlier times, and their activities are often associated

with at least two general revolts (Peasants' 1381ce, Jack Cade's

1450ce) as well as other, lesser, riots. Particularly following the

Black Death in 1349, wandering (i.e. non-aligned, un-associated,

non-guild) minstrels were at continual risk of penalties for vagrancy

and more serious charges.

One last nod to the _Britannica_:

"The term minstrel covered a great variety of performers."

Significantly, at least according to one modern authority:

"There is no real equivalent to the Celtic Bard

in Anglo-Saxon England..."

Refining the Scope of the Discussion: Pre-Christian Bardic Origins

For terms of a general discussion, serious consideration should

be given to the so-called "hedge-Bards", as those certainly seem to

have been responsible for carrying on the real "traditions of the

Bard" even after the formal ancient Pagan / Druidic schools were

disbanded or taken over by Christian influences. These were also the

folk who developed and preserved many of the most important poetic

cycles -- and most probably were instrumental in introducing the

troubadours of France to Arthur & all his band of gentlemen, and their

greatest achievements (and failures).

The "true" bards (those named Muse-poets by Graves), at least

within surviving manuscript sources, were almost invariably male in

Europe, the British Isles, and the majority of Old-World "contact

cultures" during the SCA "period" (fall of Rome to 1600CE). As with

most other professions, there were of course exceptions -- and some

traditions of "wise women" who entertained in a fashion, in addition

of course to the priestesses of pre-Christian times and non-Christian

cultures. There are significant survivals in ORAL tradition which

indicate that the woman as bard was in some places the norm rather

than the exception. Lineages can be particularly hard to trace for

another related reason: some bardic traditions also held that bards

were not permitted to marry.

Male & Female Bards: First Notes

As with other aspects of life, the "male-ness" of bards was most

noticeable in cultures that included patriarchal religious structures

and inheritance laws. (How much of this bias also revolves around the

nature of those who were making the written records -- the monks and

other Church-folk -- can only be conjectured at.) For all that the

bard was originally tightly associated with Goddess-worship, he also

represented the respect of men for the female principle. MUCH more

about this might be included were this principally a religious

What *IS* A Bard?

Page 8

discussion; as it is, some additional related comment will be found

later. As important as oral tradition has always been to bards,

scholars generally reject oral sources of information in favor of

permanent records such as manuscripts: in the manuscripts, where are

the women bards?

UPDATE (Summary):

Additional resources have been located which affirm the existence

and importance of women as fully-trained bards.

Among other items, a

woman was one of the seven harpers at an Irish gathering in the 18th

Century (Christian era) which attempted to preserve more of the

repertoire that had been passed hand-to-hand. Also collected but not

yet integrated are notes about the systematic destruction of records

by Church zealots and government officials charged with “correcting”

inheritance records (or otherwise suppressing previous claims).

The Essentials of Being a Bard

It should be reinforced here that the true-bard, the thoroughly

wonderful and honestly-complete original of which this study tries to

approach, survived historically well into SCA "period" BUT was very

much the child of earlier times. What are the essentials, then, which

form the quintessential bard? We may begin by noting the tradition of

oral histories, the role as religious teacher, the association with

"magick" such as prophecy or divination, and the incidental existence

as an entertainer. And no one aspect among these is more or less

important than any other. And the listing we start with here is by NO

means complete or definitive still. As observed by Rudyard Kipling in

reference to a hypothetical poet of still earlier ages:

There are nine and sixty ways of reciting tribal lays,

And every single one of them is right!

Bardic traditions span many variations of personal approach,

public conception, and historical context. From the earliest tribal

gatherings around the cook fire up through modern Neo-Pagan survivals

(we might even say with tongue only partly in cheek "revivals"), the

practitioner of the bardic arts has been a valued member of the

community. So much so, in fact, that poets have been blinded, strong

men deliberately lamed by hamstringing, and even fierce battles fought

over the "right" to keep a particular bard in residence. Competition,

and attendant danger for the targeted bards, became so fierce in some

times and places that it became necessary for bards to reserve to

themselves the right of free passage -- to come or go as they please

-- among other rights and defined responsibilities. As a group, bards

would enforce this by imposition of a ban against performances & other

bardic services, including their priestly functions, upon the lands

and holdings of any who violated this most basic of "bardic rights".

(For those not particularly familiar with religious history, note that

this method, often referred to simply as "the Ban", was also adopted

for use by the Catholic Church against the lands of excommunicated

nobles at more than one time and place.)

The application of the bard's power of satire as a retaliation

was a feared consequence of offending the great and the not-so-great.

In Welsh tradition, when Arawn is offended by Prince Pwyll of Dyfed,

the prince is threatened with being "satirized to the value of a

hundred stags". In one notable occasion, a bard greeted with less

than complete hospitality by an early King of Ireland composed such a

What *IS* A Bard?

Page 9

powerful satire that said King was forced to abdicate in favor of a

more generous man. {15}

Mighty bards were even said to be capable of raising blisters

selectively on a human target solely through the biting heat of their

performance. {16} Other aspects of the traditional bardic powers were

said to derive from non-worldly forces as well. Bards among the Welsh

were said to receive their inspiration and power from the _awen_, a

divine force raising the poet beyond his normal self and abilities.

In the resultant ecstasy-trance, the bard became something of a

prophet and occasionally a type of "spirit medium" as well.

In the poetic "Cad Goddeu" (Battle of the Forest), among other

sources, we find a record of the ability of the bard to change shape

into any beast, human, or natural feature (granted through

supernatural forces and also the power of personal will). The bard

was also believed to be able to send his spirit forth from his body,

in order to move through time and space "acquiring at first-hand all

knowledge". There certainly seems to be a close relationship between

bardic prophecy and shamanism (both as practiced in Siberia and

otherwise). The "Cad Goddeu" may also be one garbled record of the

Celtic cosmogony otherwise believed lost except for the version

recorded in the _Barddas_.

Assorted Notes Upon Bardic Tradition & Contributions

In his role of priest in the pre-Christian faiths, the bard was

also associated with the gods, just as "the shaman in his ecstasy in

any case [is] identified in part with the god". {17} It was believed

that in at least two locations, Cader Idris or under the Black Stone

of the Arddu on Mount Snowdon, an individual spending the night would

descend the next morning as either a madman or a bard.

The "triduan" is a ritual fast of three day's duration meant to

induce ecstatic trance and visions derived from usage by bards. It

was one aspect of Druidic and bardic existence that was particularly

absorbed into British and Irish Church practices, with very few

changes made to hide the guilty. (Fasts are associated with religious

practice in many ancient / "primitive" cultures, particularly those

with belief in seers and prophetic visions.)

The _Glossary of Cormac, dated to the 9th century ce, tells us of

the "tugen", or bard's clothing, made of the skins of both white &

many-coloured birds. This garment was also called the "enchennach",

and is believed to have included in particular the feathered hides of

the wild ducks that could be captured. Reade tells us:

Their ordinary dress was brown, but in religious ceremonies they

wore ecclesiastical ornaments called "Bardd-gwewll", which was an

The bard in question had been given sub-standard lodging,

bad food, and not even a mug of good ale. There are *reasons* why

the Irish believe in providing hospitality...

15

It is now known that the same effect can be reproduced

through modern hypnosis...

16

17

Tolstoy, pg. 142

What *IS* A Bard?

Page 10

azure robe with a cowl to it -- a costume afterwards adopted by

the lay monks of Bardsey Island (the burial place of Myrrddin or

Merlin) and was by them called "Cyliau Duorn", or black cowls; it

was the borrowed by the Gauls and is still worn by the Capuchin

friars. {18}

A great bard's income could be astounding indeed. One hundred

horses, cloaks, and bracelets, along with 50 brooches "and a

magnificent sword" were given to Taliesin by Cynan Garwyn at Pengwern.

Cattle, mead, oil, and even serfs were also included in rewards and

largesse.

Historical Resistance to Bardic Influence

An important side-note, a matter which I only recently become

aware of through the good graces of an electronic copy of Rosario di

Palermo's previous Collegium Gradium presentation concerning

"defenses" of Poetry within the Classical, Medieval, and Renaissance

timeframes: poets in general, of whatever type, were barely tolerated

by the Church and other authorities for many centuries. Before the

rise of the Church, philosophers since at least Classical Greek times

(Plato and Socrates in particular) objected to the inaccuracies of the

poet's language.

This was based primarily upon the imagery of the poet being

imitative while Philosophy was thought to be a direct revelation of

Truth; but there was also a lesser but still-strong argument based

upon morality (in the words chosen by Rosario: "...it can be dangerous

to the moral health of the state if poets discuss immoral acts.

They

may set a bad example by appealing to the baser instincts of man.")

Graves (_The White Goddess_) noted in reference to Socrates'

attitude a quotation from the philosopher himself, in which the man

rejected myth in favor of "everything as it is, not as it appears, and

to reject all opinions of which no account can be given". The modern

author further addressed the classical by noting that:

... by Socrates' time the sense of most myths belonging to the

previous epoch was either forgotten or kept a close religious

secret, though they were still preserved pictorially in religious

art and still current a fairy-tales from which the poets quoted.

Graves' claim is also that Socrates was turning his back on the

Goddess principle and religion in favor of "intellectual

homosexuality", even in the face of direct experience with the power

of magic within the philosopher's own lifetime (as evidenced by the

actions, and results, of the priestess Diotima Mantinice in stopping a

plague in Athens).

All of this led in part, later on, to one of the more humorous

paradoxes to face the organized Christian Church in Europe. While

bards, minstrels, and other notorious poetical sources wandered the

countryside spouting allegory and fable, and generally being denounced

for their heresies in doing so, the churchmen found that the (thanks

for the phrasing once again, Rosario!) "only way to teach large groups

of people the faith was by example, by allegory -- by stories.

Jesus

18

Reade, pg.83

What *IS* A Bard?

Page 11

himself taught by means of parables and stories..." Churchmen and

secular writers who used poetic forms both often resorted to the "it

was all a dream" claim in order to avoid sanctions, and often wrote

letters of general retraction to be released upon their deaths (Refer

to Rosario's paper for some interesting notes upon the Retraction

penned by Chaucer; consider also the apocryphal tale of Marco Polo's

deathbed refusal to issue any retraction: "Father, I only told the

*half* of what I saw!")

Nikolai Tolstoy comments: "With the establishment of

Christianity, the role of the bards was greatly reduced." Previously,

the telling of the genealogy of the new king or other great chief

included a prophecy as to his successors. Tolstoy's sources otherwise

also attribute this portion of the ritual of elevation variously to

druids, "a Highland sennachy", and "the Orator" at differing times and

places. As Churchmen took over the sacred portions of these rites,

the tradition of prophecy concerning the future succession was

abandoned.

BARDIC RIGHTS AND RESPONSIBILITIES

As we have spoken of a few of the rights and responsibilities of

bards, this might be a good time to consider a brief &

still-incomplete list of some of the most commonly acknowledged duties

and abilities that should be considered the province of a bard.

Appendix B is one version of such a partial list (along with related

commentary).

An ancient British law held three classes of employment

("professions") to be free from slavery: smiths, scholars of

languages, and bards. "When once the smith had entered a smithy, the

scholar had been polled [?], or the bard had composed a song, they

could never more be deprived of their freedom." {19}

As an (expanded) extract, consider that a "true Bard" might have

been called upon to fulfill ANY of the task-names which are shown in

the following list at some point in his career: go-between, judge,

neutral party, arbitrator, law-keeper (NOT -- usually -- law-*giver*),

satirist, saga-singer, poet, musician, herald (particularly in some

cultures in the sense of "the voice of the King", or ambassador),

story-teller, composer of music, maker of riddles, teller of parables,

historian, herbalist / healer, newsman, news commentator, messenger,

teacher, student, priest, warrior, linguist, craftsman, record-keeper,

genealogist, military scout, spy, etc.

There is much else which is also considered to be in the province

of the Bard. Indeed, there is very little which is *not* to be

expected of a true Bard, in either lesser or greater degree, at some

time within his or her current lifetime on this plane. {20}

Indeed, and in both deeds and in fact, much that we associate

19

Reade, pg. 83

The vast bulk of evidence indicates that the "historical"

True Bard not only believed in reincarnation of some type, but

also believed himself one of the culminations of the cycle.

20

What *IS* A Bard?

Page 12

with the "typical" Code of Chivalry has a direct relationship to the

expected behaviour attributed to a bard. Consider this: perhaps the

greatest bards of all have no titles nor need for them, at least as

they go about their primary work. Bards use among other tools the

parable as a way to teach others, and are expected to interpret the

laws of the land (and the religion!) so that even the simplest farmer

can understand it readily. If one is willing to expand their worldview slightly, this makes one Yeshua bar Maryam the greatest bard to

ever walk the planet we call Earth. Yes, that is right: Jesus of

Nazareth was by all rights a shining example of what it is to *be* a

Bard (ignoring for the sake of THIS argument the significance of

events of a purely religious nature and interpretation within this

mortal life-frame -- I leave it to your personal discretion as to just

how this may be accomplished...)

Bards as Judges & Lawyers

As noted above, one particular duty of bards was that of "keeping

the Custom": remembering, interpreting, and sometimes even passing

judgement upon a basis of Customary Law. As a portion of this

responsibility, Bards would occasionally go to great lengths in order

to preserve their neutrality in the consideration of a particular

situation: relocating from the noble's comfortable tower & kitchens to

a village house or even a rude camp in the woods, refusing to listen

to any portion or word concerning the case in advance of the hearing,

and even leaving the region entirely once a judgement was rendered.

This is not to say that all called "Bard" were so conscientious: every

cellar has its dusty corners waiting to be swept, and money or the

promise of power has been known to speak more loudly than the

righteous...

Bards as Historians & Genealogists

A related function of the bard, one which was especially

important in determining the chronologies of the past and as a

reinforcement to the scanty formal written records of birth and death,

was the maintenance of the genealogical records. Whether in formal

rolls or chanted saga, knowledge of where one stood in relationship to

an ancestor also placed the individual as regards the great moments of

history. Well into the late Renaissance and even beyond, it was

common practice for the chroniclers of the European world (as well as

elsewhere) to record dates in reference to the ecclesiastical calendar

(how can we not remember St. Crispin's Day, with our perspective given

us courtesy of that playwright-fellow from Stratford-on-Avon; who

would not know the time of the year when All-Saints Day was to be

celebrated?) in combination with the time since the accession of the

local monarch, or in reference to some Great Event ("in the Third Year

of the Reign of Our Good and Righteous King Richard, Known to All the

Christian World as the Lion-Heart", "in the Fourth Year Following the

Great Siege of Our Duke Jean's City of Calais", and other similarly

flowery artifices were more common than we of the modern age often

acknowledge).

Keeping the genealogy was further exceptionally important due to

the importance of maintaining the lines of succession, particularly

for tribes and clans where political and religious power both were

matters reinforced by hereditary rights. And, to no particular

surprise for modern ears, where death due to disease was even more

common than death due to violent means a successor from collateral

lines of descent was needed a bit more often than we today find

What *IS* A Bard?

Page 13

comfortable or likely. The need to prove relationships to a currently

powerful ruling family was also important for other reasons: a man or

woman's starting place and opportunities within the social and

political structure was determined almost entirely by birth-rank.

Position at table, potential marriages, opportunity for service as a

military officer, and even suitability for consideration as a

clergyman OR as a "true" bard all could derive from nothing more than

one's relationship to the current chieftain, baron, jarl, or

what-have-ye. If you could not prove your parentage, there was even

the possibility of severe penalty for impersonation of a person of

true rank and privilege.

Bards as Peacemakers

Bards were also noted as restorers of the peace, as well as

inciters of heroic deeds. The old tales tell of more than one

instance where two armies in full array faced each other across the

field, only to be kept from the fight by the power of the bard's song

and reasoning of his arguments.

Language Drift as the Bard's Foe

All of this was made more difficult with succeeding waves of

migration, invasion, and conquest. Tracing back through the oral

records afterwards gives us some peculiar difficulties for the

occurrences of the remote past. Language changes with time, even

given the best efforts of well-intended historians, grammarians,

churchmen, and bards. So do systems of calculating relative position

in regards to some historical event. For example, three of the royal

figures associated with the supposed "historical Arthur" all have

names translating to some form of "king" and almost certainly were

titles before they were names (or were perhaps adopted when they

ascended the throne, after the manner of the Roman Emperor, and later

the Pope): Rigotamos (Riothamos) = "kingmost", Vortigern = "overking",

and Vortimer = "kingmost". {21} Instead of dating from the *birth* of

Christ, an earlier method created by a churchman named Victorius was

based upon the *death* of Christ, placing it in 28CE (784AUC). And,

unlike current practice, there was no consistent nomenclature used

which might otherwise distinguish between the several variations.

When combined with other inaccuracies, and even some proven blatant

distortions of the written record, ....

CULTURE AND BARDIC TRADITION

In the dawn of civilized history, tribes were small: it was a

time when everyone could sing the oldest or the latest songs or tell

any of the great tales with amazing accuracy. "In the old days,

pretty much everybody did a little bit of everything, and that

included music-making." [Bookbinder, pp60-75] "Songs and spoken tales

were the way the great mythological stories were carried from

generation to generation." [Bookbinder pg 51] The archaeological

record shows the use of buttons in Ireland at least as early as

1900bce; a rapier dated reliably to 1200BCE rests now in the National

Museum of Ireland; torcs of twisted gold have been found which are at

least as ancient as this blade. {22}

It also appears that Midas was a title in ancient Phrygia

and not on the whole a personal name.

21

22

See

Harbison,

What *IS* A Bard?

_Pre-Christian

Ireland_,

for

additional

Page 14

Even well into the modern age, traditions about the makers of

poetry and music as holding supernatural power (along with related

beliefs), survived among aboriginal peoples around the globe. A few

examples from the New World may be particularly illustrative of some

ways that proto-bardic manners and methods influence tribal life -and the importance of "bards" to that life, when they are present:

In several tribes, one measure of the passage into adulthood was

the creation of a personal song by the candidate. Particularly

among the Plains tribes in North America, the concept of the

death-song was also strongly embedded in the warrior mystique.

The medicine-man or shaman was responsible in most tribes for

educating the young people through story, song, and parable. His

(or her!) apprentices were required to pass through a long course

of memorization of lore, history, and genealogy.

Healing ceremonies typically include the use of chants, drums,

rattles, clappers, and herbal medicines. Divine intervention is

invoked by song and action.

Signal drummers in eastern Ecuador and Peru use both "male" and

"female" drums to reach more than twelve kilometers.

In much the same way that Celtic bards used satire, among the

Eskimo "... conflicts here are not settled by fighting, but in a

drumming contest by the persuasive power of the songs with which

the opponents mock each other and reveal their mutual weaknesses

and shortcomings." {23}

It is well known in our time that Europeans treated in-period

information returning from the Americas by European standards, and

ignored "the magical and ritualistic function of Indian music and the

special way it was bound up with their religion and their whole way of

looking at the universe". {24} Much was made of the fact that natives

of the America trained in the Spanish musical style were considered

creators of compositions that were indistinct from the Europeans' work

(an observation noted in a manuscript attributed to Juan de

Torquemada, Seville, 1615ce).

Today, late in the 20th century CE, we realize that for the

natives of the Americas, the so-called "Indians", as for most socalled "primitive" cultures:

[...] music is not an art, but an expression or manifestation of

life. Generally speaking, he would hardly describe it as

"beautiful", but rather as "powerful" or "effective".

Music for the individual represents a source of power and

for the tribal association a means of reaching an understanding

with the supernatural beings from whom they ask for all good

things.

The music of the Indians is essentially religious and is

related information.

23

_Music of the Americas_, through pg. 30

24

_Music of the Americas_, introductory material.

What *IS* A Bard?

Page 15

functionally bound up with worship [...] His music is an

expression of his beliefs and hopes and his fear of the gods.

{25}

In illustration, it should be noted that Mexico prior to the

arrival of the Spanish had an "Academy of Fine Arts" at least in

function, a school where singers, dancers, and musicians all met to

receive training and trade information; the Lenni Lenape maintained a

tribal chronicle in pictographs carved on wood said to trace back to

the Flood; in Tierra del Fuego "The harsh austerity of their

environment greatly developed a strong inclination toward magic and

religious conceptions. They had a rich store of myths". {26} At least

some Native American oral traditions speak of ancient inter-tribal

training centers attended by the medicine people of the tribe, both to

give and to receive knowledge.

Bards in Historical Record & Belief

In the particular context of this study, a good many people today

believe that TRUE bards were and have always been at least in some way

a part of the "Druidic" and other related religions, especially those

practiced by the pre-Christian Celtic tribes and clans. {27}

Particularly, bards are identified as possessing magical powers and a

history of at least partial accuracy as predictors of the future.

We have records, by way of the Greeks and Romans in particular,

of Celtic beliefs before the advent of the Christian faith: Celts

sacked Rome itself in 370bce, Delphi in 273BCE; they were allies of

the Etruscans in the Third Samnite War and later friendly with

Alexander of Macedonia (his agreements with the Celts maintained his

northern border during the great campaigns into Asia Minor and other

places); and the gathered tribes delivered one of the most stunning

Roman defeats in pre-Imperial times. {28} Herodotus knew of the Celts

in Spain, Aristotle knew that they "set great store by war-like

power"; Ephorus noted them as using "the same customs as the Greeks" &

being on friendliest terms with those who established guestfriendship; and the Celtic oath-formula as recorded by ancient sources

remained unchanged for a thousand years. (In paraphrase: If we fail,

may the sky fall on us, may the earth gape and swallow us, may the sea

burst out and drown us. {29}) Celtic place-names survive all across

25

_Music of the Americas_, pg. 31

26

_Music of the Americas_

I know from

which is evidenced

modern survivals of

prefer, "neo-Pagan"

Americans who still

27

personal experience the reverence for Bards

by those who perform their worships in the

the Wiccan and compatible Pagan -- or, if you

-- religious systems. And among those Native

revere tribal ways.

This was "dies Aliensis", July 18, 390BCE: in response to

Roman treachery the previous year at Clusium, the Celts attacked

into Italy and were met at the River Allia. The Roman defenders

were annihilated in one tremendous Celtic charge.

28

This oath was sworn to Alexander two centuries BCE, and was

recorded in the 1100's CE in the _Book of Leinster_ as part of the

Tain Bo Cuilgne {pronounced approximately as "tawn bow kwelgney",

29

What *IS* A Bard?

Page 16

Europe. Celtic dialect even survived among the "natives" of Galatia

in Asia Minor until the 4th century CE.

Practically all of the ancient European tribal peoples, Norse &

Cymri & Scotii & Angles & Saxons & Celts most especially included, had

no widespread written language before the spread of the Greek alphabet

BUT all had a mythological way of looking at the world and "... an

accompanying system of songs, tales, and rituals". These became

codified as the great epics, which were the particular province of the

bard. The labor of memorization and maintaining this information was

considered essential to the life of the tribe, clan, village, or other

similar social unit. This led in turn to many of the other privileges

and more importantly the responsibilities associated with bards.

Diodorus Siculus "mentions the great reverence paid to the bards".

{30}

Bards as Literate & Non-Literate

Although much effort has been expended by scholars through the

ages in reducing the oral tradition bard to an unlettered class, we

must note that the Celtic Ogham and the Norse Runes were both closely

related with bards, druids, priests, and skalds. For the Celtic Druid

and bards raised up in that tradition, there were in fact extreme

prohibitions AGAINST recording of certain parts of the "secret

knowledge" in written form. Even so, we know that learning in the

"classical" pen&paper sense was not only done, but was actively

encouraged. Gaius Julius Caesar, speaking of the Druids and their

doctrine, tells us: "They are said there to get by heart a great

number of verses; some continue twenty years in their education;

neither is it held lawful to commit these things to writing, though in

almost all public transactions and private accounts they use the Greek

characters." Caesar also commented upon the Druids as being general

teachers of the young, and the Celtic day starting at sunset (phrased

as "the coming of night"). Strabo, the geographer and traveller,

noted the Celts of Gaul to be eager for culture, with public education

in the towns and the spread of Grecian learning outward from Marsillia

(Marseilles) being encouraged.

Druidic & Celtic Origins of Bardic Tradition (and Tales)

The Druidic "sacerdotal" (priestly) authority controlled and

restricted both religious and secular learning according to some

sources. Professional poets, the "fili", are noted in the same

source: they "were a branch of the Druidic order". No reliable record

of the ancient Celtic creation myth is believed to exist, the earliest

manuscript directly describing and attempting to explain the Creation

is the _Barddas_ (detailed later). Otherwise, the *surviving* tale

cycles start with the Invasions of Ireland. There are five invasions

noted in what is also known as the Myth Cycle (or Cycle of the

Invasions): Partholan, Nemed, Firbolg, Tuatha de Danaan, and the first

purely human, the Milesian. (The preceding four groups are all

accorded status as supernatural in some manner, particularly as gods,

goddesses, and monsters. The other two cycles agreed upon by most

known better to most English-speaking audiences as "The CattleRaid of Cooley"}, which is believed to have been formalized in its

oral structure approximately 800CE.

30

quoted in _Celtic_, Rolleston, pg. 42

What *IS* A Bard?

Page 17

antiquarians studying Irish mythology, legends, manuscripts, and

poetry are:

the Ulster or Ultonian (Conorian), best known for the "Tain Bo

Cuilgne" with the great hero Cuchulain,

and the

Ossianic (Fenian), which dealt primarily with the Fianna (a

"King's Guard" originally intended to deal with external

invaders), whose chief captain was Finn mac Cumhal and which

served King Cormac mac Art and later Cormac's son Cairbry.

Finn's son Oisin (Ossian, pronounced Oooo-sheen) was acclaimed as

the "greatest poet of the Gael. "The Maxims of the Fianna" read

like the Rule of a chivalric order of knights, although the

membership was decidedly less genteel even than the band

associated with King Arthur...

In addition there is a great wealth of material which is largely

unconnected to any cycle other than by reference to the Tuatha and

other non-human powers or legendary heroes appearing as ancestors, or

spirits returned to impart knowledge to those still living. The most

consistent and best-known of the "non-aligned" tales are those

concerning miraculous voyages; by far, the most widely known of the

voyage tales that survive were typically associated with Christian

themes. St. Brendan is often cited as a possible pre-Columbus

discovery of North America, although other evidence indicates that the

record is much more that of a spiritual rather than a physical

odyssey. _The Book of the Dun Cow_ and other early sources give us

such entertainments as the tale of the "Voyage of Maeldun", attributed

to Aed Finn "chief sage of Ireland" (who is unfortunately not

otherwise recorded in modern records).

It was not until the two-volume _Barddas_ was compiled by

Llewellyn Sion of Glamorgan toward the end of the 16th century CE that

it is thought anywhere near a relatively full record of the material

previously prohibited from being taken down in writing was made in

manuscript form. {31} The attacks upon this work by modern scholars do

call it into question, and the work itself makes no pretense of being

PURELY Druidic/bardic, containing much Christian history and

biography. An independent strain of earlier, non-Christian thought is

still very evident and recognizable, however.

The Requirements of Acknowledgement

Among the Welsh (at least as we are told things in these later

times) the word "Bard" denoted a master-poet, and there were very

definite requirements which had to be met before the title was

granted. What is now considered the first major school, that of

Rheged "the Cumbrian kingdom", included the legendary bards Taliesin

and Aneirin (who are known to have been present at the fall of

Catraeth in 598ce). Welsh court feasts certainly included musical

accompaniment, but the bards in attendance served additional

functions:

My tertiary source named J.A. Williams ap Ithel from the

Welsh Manuscript Society as editor and translator of _Barddas_. I

have not yet managed to inspect a copy for myself and thus only

pass along the reports of others. The quoted portions which I have

seen have left me anxious to make a deeper inspection, though!

31

What *IS* A Bard?

Page 18

In times of peace the kings drew moral support from their

court bards. The bards were prominent figures -- entertainers

certainly, but a great deal more than that, inheriting some of

the Druid's functions. They were the authorities on customs,

precedents, pedigrees. Their poems, sung to music, extolled

their royal patrons and had what would today be called public

relations value, projecting the King's "image" as a man of august

descent, martial renown, bounty, and so forth. Praise of the

same sort was extended to his forebears and followers. {32}

The Bardic Triads

It is also noted that "Through the bards' poetry, their oral

storytelling and popularization, the Arthur of the Welsh took shape."

It is a humorous relic of the Welsh "Triads" (sets of three, and

sometimes more, related tales addressing a certain virtue or failing)

that Arthur of Britain is recorded as being one of the Three Frivolous

Bards. This appellation was earned when "he annoyed Cai by

extemporizing a verse about him". {33}

Another of the great bardic traditions described in Triad form is

specific to the harpist: to be acclaimed a master of the harp, the

harpist was expected to have full command of the "Three Noble

Strains", Lament, Laughter, and Lullaby (or Slumber).

Welsh vs. Irish Distinctions

If we follow the arguments of Rolleston, we see that the

objective of the Welsh bard, who had his duties fleshed out later than

the Irish, was less the preservation of sacred "text" (orally

transmitted, of course) and more the entertainment of the princely

court. Continental influences, particularly chivalric romance, enter

the Welsh tales early and "eventually [...] govern them completely".

The tales of the Mabinogion as we know them today derive mainly from a

14th century CE manuscript known as _The Red Book of Hergest_, the

earliest four segments having possibly been composed in the 10th or

11th centuries CE.

The romance of Taliesin (a different Taliesin than that

associated with the primary bardic school at Rhedeg, possibly) was not

placed in manuscript form until the very late 16th or perhaps the 17th

century CE. Another manuscript known as the "Hanes Taliesin" may have

been recorded in part from material *created* as much as 800 years

earlier, but still not reduced to written form until much later.

By comparison, the oldest extant Irish forms date to the 7th or

8th century CE ("Etain and Midir", "Death of Conary").

Arthur the King: Latter-day Bardic Material

The Arthurian tale cycle, although fed in part by the Welsh and

Breton sources as well as presumably older material from Britain

itself, were driven much more by the romances of the European

continent than by bardic sources generated before the conquest of the

Anglo-Saxons by the Normans. The earliest extant manuscript reference

32

Ashe, _The Discovery of King Arthur_, pg. 136ff

33

Ashe, _The Discovery of King Arthur_, pg. 141

What *IS* A Bard?

Page 19

to Arthur which the modern world is aware of dates to 800ce {Nennius,

_Historia Britonum_}, wherein he is accounted a "dux bellorum" or

"duke of war", less noble than many who answered to him. By the time

of Geoffrey of Monmouth, the legend had grown and Arthur was king by

right of birth AND also right of arms. And Modred was only a

nephew.... and more and more material was being integrated from a

variety of oral sources, notably from Breton France and Wales.

Note well that "the Matter of Britain" is no less an important

topic for bards both ancient and modern. However, just how much of

the whole is used in performance and which variation upon the given

story is presented can vary widely depending upon the origins and

nature of the specific bard who is performing.

Irish Bards: Students on the Road, Princes of the Land

For the Irish, "bard" was used to name poets who were not yet

advanced to the status of an Ollave, folk who were not fully trained

in the formalities (having not yet completed the full twelve year

course of studies and memorizations). These lower-status Irish Bards

seem to have been at least on the same general level of competence as

those given the full title amongst the Welsh, at least on the basis of

their education in poetry and other knowledge. The title appears to

have generally been accredited to their efforts after a seven year

course of study, in which they would have learned approximately onehalf of the required volume of material required to attain the full

rank of Ollave. These are the people sometimes referred to as

"hedge-bards", a term popular for its imagery at least among some

modern students (Ioseph of Locksley, "ye Whyte Bard", has particularly

defined and attempted to popularize this term for the SCA audience.)

Ollave were given status equal to the kings and queens of the

land, and along with them were the only folk allowed to wear more than

five colors at the same time. {34} Filidh, "seer", was a title that

was parallel to that of the Ollave and generally more associated with

spiritual matters, particularly those of the pre-Christian religion.

The Ollave were doctors and lawyers, diplomats, and otherwise

counselors in worldly matters. In fact, perhaps the most

distinguished of all Ollave was Ollav Fola, named in the traditional

lineages as 18th king of Ireland after the arrival of the Milesians

(living approximately 1000bce). He was responsible for the

codification of law, allotment of territory, and otherwise delineating

the rights and responsibilities of the provincial chiefs, and also

instituted the great triennial Fair at Tara "where the sub-kings and

chiefs, bards, historians, and musicians" all gathered to compile

genealogy, enact law, argue disputes, and decide succession. It

became an inviolate tradition that no one could attack another or even

begin legal proceedings while the Assembly at Tara was in session.

Bards as Conservators of the Old Paths; Irish Influence on the Church

A practice introduced by the fifth Milesian king, Tiernmas,

was control of "variegated colours in the clothings". Slaves were

allowed one color, peasants two, soldiers three, wealthy

landowners

four,

and

provincial

chiefs

five.

"It

is

a

characteristic trait that the Ollav is endowed with a distinction

equal to that of a king." Rolleston, _Celtic_, pg. 149.

34

What *IS* A Bard?

Page 20

"We know that certain chiefs and bards offered a long resistance

to the new [Christian] faith..." One result was a great battle at

Moyrath in the sixth century CE. Another was the modified form that

the Church took in the Celtic lands of Ireland and Scotland, including

some customs and superstitions that eventually were adopted or reintegrated into worship throughout the Christian world. Consider the

particularly the far more visible role of women within the Church, the

form of the ritual fast, and the importance accorded Mary the Mother

after the Irish were brought into the fold...

Passage of the Old Way

In roughly 800ce, the ascetic Aenghus recorded that almost all of

the most famous forts and cities from the great and storied past were

gone (only Armagh survived in a form recognizable from the epics):

Tara's mighty burgh perished at the death of her princess; with a

multitude of venerable champions, the great height of Machae

abides

Rathcroghan, it has vanished with Ailill, offspring of victory;

fair the sovranty over princes that there is in the monastery of

Clonmacnois.

Ailenn's proud burgh has perished with its warlike host; great is

victorious Brigit, fair is her multitudinous cemetery.

Emhain's burgh it hath vanished, save that the stones remain; the

cemetery of the west of the world is multitudinous Glendalough.

{35}

STYLE, MATERIAL, and FORM: TRACING THE BARD'S DESCENT

The scop, the skald, and the bard originated at least in part as

an outgrowth of the epic tales, or the closely-related Norse sagas. It

required special training to be able to repeat the many thousands of

lines which made up the great epic without error, and in an

entertaining fashion. Later, as the written word became more important

throughout society and an expanding body of work was available in

manuscript, sagas sung across several days fell out of favor. At least

one very important factor was also the rise of Christianity as the

dominant religion, remembering that most of the oldest sagas and epic

poems served also to preserve the former religions. Epics especially

were considered sacred, stories preserving the tribal and cultural

world-view from generation to generation by word-of-mouth. Both saga

and epic were often tied closely with particular ceremonies: between

hunts, before or after battle, during the depths of the winter-time, at

the spring fairs and harvest feasts, and whenever else. Life speeded

up, the old festivals fell into disuse, and the saga-singers' tales

passed out of fashion in favor of the new form: the ballad.

The earliest ballads (let us _loosely_ define the ballads to be

"songs which tell self-contained stories") not only date far back into

feudal times, but also preserved smaller episodes drawn from the great

long-winded epics.

They could be performed in minutes, not hours.

Over the course of time, they became more realistic, more personal, and

covered a greater variety of subjects. As the ballad became more and

more the most often requested style, it was also to drive the new

generations and developing "schools" that followed which were in some

way related to the ancient bardic traditions.

The Troubadours,

35

Harbison, pg. 194

What *IS* A Bard?

Page 21

Trouve`re, and general minstrels were but some of these.

The Troubdour: As Historically Acknowledged

It is generally accounted that there were but 400 acknowledged

troubadours across a time-span of approximately two centuries.

(The

last person considered a troubadour in all ways, Guiraut Riquier, died

in 1294CE at the age of 64.) Just as the Welsh are notorious for the

strictures

of

"The

Four-and-Twenty",

so

were

the

troubadours

particularly associated with a limited number of formal verse forms

(albeit they were less restricted overall in their structures).

The

"joc partit", "partimen", and "tenson" were all conversational lyrics:

some number of persons discussing general matters of love or even

religious and satirical themes. The "canzo" was the most common form

and consisted of five or six stanzas and an envoy ("coblas" &

"tornada").

The "sirventes" was a canzo with satirical or political

overtones (sometimes sirvente are spoken of as a precursor of the "filk

song").

"Balada", "pastorela", "alba", "dansa" (associated closely

with the balada, and both being dance tunes including a chorus), and

"serena" were the other primary forms.

The *RECOGNIZED* troubadours, and their close cousins the

trouve`re were all apparently of noble rank, or at least generally

accepted as such within their lifetimes. (At least one appears to have

begun his career in a kitchen scullery, but seems to have been a

partially acknowledged nobleman's bastard and was accorded rank to

match his achievements, as an accomplished poet within the formal

styles and also within other areas, later on.)

The Trouvere: Love As All

Trouve`re seem to have originated in the court of Louis the VII

and Eleanor of Aquitaine. There was really only one subject to which

they devoted themselves, and that was some variety of Love.

Eleanor

happened to be the granddaughter of one of the best-known of the

troubadours, lending credence to the timing and source of the initial

influences of the tradition.

Just as with the troubadour, these

rhymers were particularly associated with a limited number of verse

forms:

"estrabot"

(a

relation

of

the

Italian

"strambotto"),

"rotruenge", and "serventois" (MUCH more ribald than the sirventes from

the troubadour repertois). The great centers of trouve`res writing and

performance were Champagne, Paris, Blois, and at the last Arras. The

system seems to have disappeared for all practical purposes before

1281ce.

Beyond Chivalric France: Germany

German Minnesinger also grew out of the troubadour / trouve`re

tradition, and were succeeded in the course of time by the

Meistersingers. There are some authorities who consider this to have

been a stifling fossilization, and others that seem to treat the

transition as providing a continuity sorely lacking in previous times.

Minstrels: Poor Cousins & Peasants

Minstrels we have already considered at some length.

It is

reasonable in some ways to ignore them if we are trying to trace the

"true" bardic tradition, but it is most unwise not to consider their

impact upon their more formally-developed cousins. The minstrel had no

great store of tribal lore to preserve, seldom was entrusted with

special privilege other than the making of music, and answered to no

particular secular authority other than the ruling nobility where he

What *IS* A Bard?

Page 22

happened to be at the time. Few held positions for any great length of

time & many were relatively limited in their endeavors to a single

instrument or vocal repertory.

Some pedantic views maintain that it is precisely this new-fangled

insistence upon specialization which keeps us from considering

minstrels as bards in the "old sense".

The oral tradition was not

there, and the sense of responsibility was seldom recognizable in any

but the most conscientious. Naetheless, the minstrel presence in ways

did continue a general awareness of at least some of the most important

bardic customs and methods, even if it tended to the informal.

Minstrels also were more influential in their communities than is

generally apparent (note again the place of wandering performers in

beginning / inciting rebellion -- and the dangerous official view

connecting them with the spread of plague...).

Ending the Road: Printing as the Death of Wandering Minstrels

Printed broadside ballads date to the beginning of the 16th

century of the Common Era, and mark yet another decline in the fortunes

of wandering minstrels and struggling bards. Combined with the rapid

spread of the presses that produced them and the flood of histories,

commentaries, news-sheets, and other printed materials, the audience

for orally-transmitted news and history began to disappear rapidly.

The circle had spun again, and it was once more a time when everyone

had access to and could sing the latest songs, or tell the latest tale

with relatively great accuracy. {36}

Survivals and Revivals

Bardic tradition also survived in some ways in the form of the sea

chanteys. A Venetian friar recorded information about these workingsongs of the seafarer in the fifteenth century CE, but the examples

best known today date mostly to the period between 1830 and 1870CE -the time of the "tall ships", the Brito-American packets and clippers - or are even more recent creations.

One "last bastion" of the bardic style, and songs, may also be

found in the folksong revivals and Neo-Pagan movements of the mid-20th

century CE.

... or at least what was PERCEIVED as accuracy. There is

room for a large presentation upon the changing attitudes of

society to the written and the spoken word over the years....

36

What *IS* A Bard?

Page 23

THE BARDIC STEREOTYPES

A number of stereotypical attributes have been developed around

the image of the bard over the millennia which, taken all together,

might paint a rather un-moraled picture of the bard as a womanizing,

booze-hugging, ne'er-do-well, as likely to make off with the daughter

and silverwork of his host as to provide relief from the tedium of a

winter evening. Ever-reliable Frank Muir tells us in his book:

The Ancients were, as usual, suspicious of something

pleasant as music. A Greek historian warned:

Music was invented to deceive and delude mankind.

Ephorus (4th cent. BC) Preface to the _History_

as

And a distinguished Roman physician wrote:

Much musike marreth mennes maners.

Galen (c. AD129-199)

Women as Bards: Conjecture and Acknowledgement

Following the original presentations of this material, one lady in

particular commented upon the implication that the only bards who were

important historically were male. She did so in the most appropriate

of manners, through poetry, much to the enjoyment of many and my own

chagrin. There are several rationale upon which she was able to build

a case to the contrary, that there must have been women who were bard,

that in fairness should be noted and expanded upon here.37

Church decree wiped out much of the "custom" and imposed

patriarchal values upon the whole of Europe.

As the written records

were almost invariably preserved only at the sufferance of the Church,

it is expected that many manuscripts were lost utterly.

Bards were charged with maintaining the genealogies, and in some

cultures the children of bards were entitled to follow afterward. As

some of these societies were also matrilinear in determining the line

of descent, and it was well-known that the only absolute means of

tracing heritage was through the mother, bard-right would by necessity

have passed in likewise.

Surviving tales and poems that can be traced reliably through

manuscripts and other evidence to the bards of old are invariably

concerned with topics primarily of concern to men.

Are we to believe

that in Celtic societies that were so rich in oral tradition, that

accorded women so many other equalities, that gloried in every

expression of talent, that the women would not have insisted upon their

own tellings, and preservation of their own versions of the truth?

The great epics that have come down to us deal in

changing panorama. Surely there must have been those

intimacies and torments of everyday life, the joys of

well as the bitter tears and lamentations of smaller

untimely passing of a child.

sweeping, worldwho dealt in the

hearth & home as

losses like the

Llereth Wyddfa an Myrddin, untitled poem, 30

ASXXVIII. Lady Llereth has been known to perform the

regularly in Ansteorra, but has not authorized publication.

37

What *IS* A Bard?

April

piece

Page 24

Especially, it is impossible to believe that all the great wealth

of folk music preserved in the memories of the remote areas in the

British Isles could have come only from the voices and talents of men.

For what is folk music in this sense if it is NOT the truest survival

of the bardic gift of preserving knowledge?

Ill-said: Bad Press for the Bard

Many of the more negative general images come down to following

all the corruptions of the ages, and the inaccuracies of equating all

wandering entertainers with "BARD".