Ridge to Reef Watershed Project - National Environment & Planning

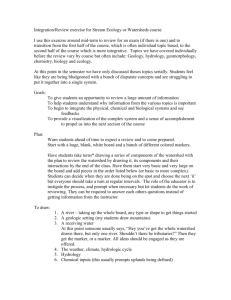

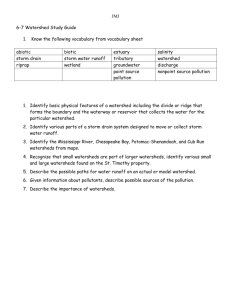

advertisement