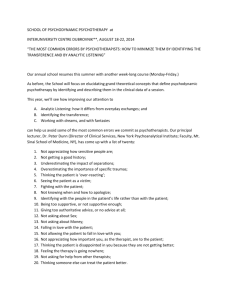

Notes for Lectures on the Concepts of Transference

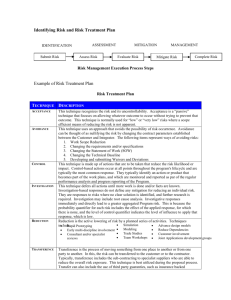

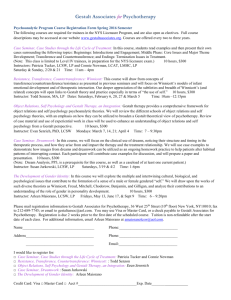

advertisement