IGA-520 - Harvard Kennedy School

advertisement

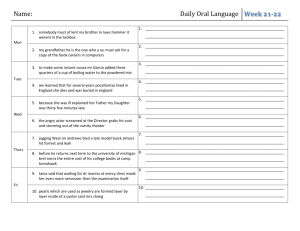

COURSE SYLLABUS IGA-520 Political Economy of Innovation for Sustainability L-130 Spring 2014 Faculty: Calestous Juma Office: L-356 Telephone: 617-496-8127 Email: Calestous_Juma@harvard.edu Office Hours: Mon 2-4 & Tues, 10-12 (by appointment only) Lectures: 8:40-10:00AM Mon & Wed, L382 Review Sessions: N/A Faculty Assistant: Katherine Gordon FA Office: L-349A FA Telephone: 617-495-7961 FA Email: katherine_gordon@hks.harvard.edu Teaching Fellow/Course Assistant: TF/CA Contact Info TF/CA Email: Course Description Overview This course examines the socio-economic sources of resistance to the application of new technologies in addressing sustainability challenges. An understanding of what technology is and how it evolves forms the introduction to the course. It explores the relationships between contemporary innovation and ecological disruptions. While new technologies are seen by some as important drivers of economic productivity and sustainability, others point to the potential risks that such technologies pose to human health and the environment. This course aims to go beyond many of the health and environmental claims and examine the underlying socio-economic sources of technological controversies. However, the same techniques have the potential to contribute to ecological management. The course examines the political economy implications of new technological applications for sustainable development, drawing from specific case studies. It covers the following themes: (1) theoretical and historical aspects of technology and sustainability; (2) resistance to green technologies; and (3) the role of innovation policy in fostering the sustainability challenge. The core text for the class is The Nature of Technology: What it is and How it Evolves by W. Brian Arthur. The Nature of Technology is the most authoritative outline of the nature, origin and evolution of technologies currently available. Class discussions will draw from Professor Juma’s draft book, Innovation and Its Enemies: Resistance to New Technologies. Training in the natural sciences or engineering are not a requirement. Scope While the focus of the course is technology and sustainable development, lessons from other fields are used either for comparison or as sources of heuristics. The course draws examples from historical case studies, which are used to illuminate contemporary debates on the role of innovation in the sustainability transition. Expectations The aim of the course is to equip students with skills for analyzing the political and economic sources of technology controversies and identifying policy options for addressing them. This focus of the course is public controversies surrounding cases where technological change is both a source of ecological damage as well as a solution. For example, ozone depleting substances were a product of technological development. But so was the development of safer substitutes. A critical aspect of policy analysis is therefore outlining the interactions between technology, environment and economy in ways that maximize the benefits of emerging technologies while minimizing their negative impacts. The course uses an interdisciplinary approach in the design and implementation of science, technology and innovation policy to support the sustainability transition. In addition to building analytical competence, students learn how to integrate knowledge from a diversity of sources and use it to identify policy options for action. The course emphasizes the use of public policy as a platform for problem-solving. It is designed to accommodate students from all fields interested in the role of technological innovation in development. The course is conducted through lectures and discussion sessions as well as occasional guest speakers. Background in the natural sciences or engineering is not a requirement. Grading Class participation (25%) is evaluated on the basis of: (a) familiarity with the readings; (b) quality of contributions; (c) critical and creative approaches to the issue; and (d) respect for the views of others. Extended outline (25%) of about 1,250 words based on the literature covered in class and identification of case material to be covered in the final paper. Draft paper (25%) of about 2,500 covering the main contents of the paper (abstract, table of contents, introduction, analysis, conclusions and references). Final policy analysis paper (25%) of about 5,000 words covering all the contents of the paper (abstract, table of contents, introduction, analysis, conclusions and references). 2 Work process, feedback and milestones Organization of work The course runs as a continuous project starting with early topic identification culminating in a final policy analysis paper. Class presentations, discussions and additional contacts from experts in the field are used as continuous input into the paper. Every student has the opportunity to get feedback at least at three stages in the course of the semester. This is done during topic identification, outline preparation, and draft paper. There is no additional feedback provided after the final paper has been submitted. Students are expected to adhere to the deadlines set for the four outputs: topic identification; extended outline; draft paper; and final paper. Pedagogy The pedagogic approach adopted in course builds on four key elements: foundation-building; problem-solving; interactive learning; and expression. To achieve this, students are expected to read the material provided based on a set of questions that define specific problems. Classroom activities: For most of the classes, the first five minutes of each class are devoted to group discussions involving sharing the knowledge from the readings and agreeing on a set of questions and comments to be presented to class for discussion. The bulk of the remaining time is used for discussion. The last ten minutes of class are allocated to a summary of the key lessons learned. Professional contacts: The course does not involve exams but students are expected to spend part of their time reaching out to experts and practitioners in their field of interest. This is part of the learning experience but also serves as a way to develop professional contacts that might be relevant for career development or further study. Where appropriate, the class hosts guest speakers as part of the professional networking process. Feedback: The learning approach used in the course involves continuous feedback on direction and contents of the policy analysis papers. Every student has the opportunity to get scheduled feedback at a minimum after the topic identification, extended outline, and first draft. Topic identification Early identification of topics or issues that students would like to write the policy analysis papers on is essential for the effective use of the material provided for the course, identification of additional information, and establishment of professional contacts. In this regard, students are expected to identify the ideas they would like to work on early in the course. Class participation and presentations 3 Class participation is a key part of the seminar and students are expected to demonstrate knowledge of the readings. Students are required to lead discussions and to participate actively in class. In addition, students may present a summary of their work to class for discussion and input. Extended outline Each student or groups of no more than three students produce an outline indicating a topic for the policy analysis paper, research methods and relevant literature. The extended outline should provide a complete structure of the expected paper as well as indicative sources to be used. Draft paper Each student or groups of no more than three students present their 2,500-word draft papers for comments. The draft papers include an abstract, table of contents, introduction, analysis, conclusions and references. The draft papers are divided into four broad sections: (1) description of the ecological challenge that technology could help solve; (2) theoretical foundations of the role of technological innovation in environmental management; (3) case study of a technological solution to a climate change challenge; and (4) identification of policy options for action. Final policy analysis papers The final output from the class is a 5,000-word policy analysis paper that identifies policy options for action regarding a particular aspect of the sustainability or innovation challenge. The final paper is a cumulative product from the entire course. It is developed in stages that include: (1) topic identification; (2) outline of the paper; (3) draft; and (4) final paper. No sample papers from previous classes are made available. However, many of the recommended readings provide guidance on the structure of policy analysis papers. Resources In addition to the required readings, students have opportunities to contact development professionals associated with the Science, Technology and Globalization Project http://www.belfercenter.org/global/. They are supported to build professional connections with experts in their areas of interests as needed. 4 Syllabus Overview UNIT 1: ORIGINS AND EVOLUTION OF TECHNOLOGY Week One Class #1 – Mon., Jan 27: Introduction Class #2 – Wed., Jan 29: What is technology? Week Two Class #3 – Mon., Feb 3: Origins of technologies Class #4 – Wed., Feb 5: Co-evolution of technology and economy Week Three Class #5 – Mon., Feb 10: Disruptive Manufacturing Technologies: The Case of 3D Printing Class #6 – Wed., Feb 12: Lessons from History I: Coffee and Tractors [Topic memo due] Week Four Mon., Feb 17: PRESIDENTS’ DAY, NO CLASS Class #7 – Wed., Feb 19: Lessons from History II: Margarine and Recorded Music Week Five Class #8 – Mon., Feb 24: Lessons from History III: Electricity and refrigeration Class #9 – Wed., Feb 26: Technology and institutions Week Six Class #10 – Mon., March 3: Technological lock-in UNIT 2: RESISTANCE TO GREEN TECHNOLOGIES Class #11 – Wed., March 5: International diffusion of agricultural biotechnology Week Seven Class #12 – Mon., March 10: Pest-resistant transgenic crops Class #13 – Wed., March 12: Transgenic fish [Extended outline due] MARCH 15–MARCH 23: SPRING BREAK Week Eight Class #14 – Mon., March 24: Wind energy Class #15 – Wed., March 26: Transgenic trees Week Nine Class #16 – Mon., March 31: Smart grid Class #17 – Wed., April 2: Biofuels Week Ten Class #18 – Mon., April 7: Disruption UNIT 3: POLICY AND INSTITUTIONAL IMPLICATIONS Class #19 - Wed., April 9: Precautionary principle Week Eleven Class #20 – Mon., April 14: No class—writing break [First draft due] Class #21 – Wed., April 16: Biosafety, public controversy and the media Week Twelve Class #22- Mon., April 21: From market niches to techno-economic paradigms Class #23- Wed., April 23: Science and technology advice Week Thirteen Class #24- Mon., April 28: Science and technology diplomacy Class #25-Wed., April 30: Wrap-up Final papers due: Friday, May 9 *Note: all drafts due by 5PM on their respective deadlines.* 5 Class Meetings, Readings and Assignments: UNIT 1: ORIGINS AND EVOLUTION OF TECHNOLOGY The aim of this unit is to provide conceptual foundations for understanding the nature and evolution of technology. It involves a systematic exploration of definitions, origins, character and evolution of technology. It uses historical cases studies to illustrate the relationships between technology, economy and social institutions. Week One Class #1 – Mon., Jan 27: Introduction The introductory session covers the overview of the course, expectations and introduction of the course participants. Read: Hobsbawm, E. 1952, “The Machine Breakers,” Past & Present, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 57-70. Mokyr, J. 1992. “Technological Inertia in Economic History,” Journal of Economic History, Vol. 52, No. 2, pp. 325-338. Class #2 – Wed., Jan 29: What is technology? The term “technology” has a wide range of meaning. The aim of this session is to explore the meaning of technology as: (a) a means to meet human needs; (b) array of practices and components; and collection of devices and engineering practices available to a culture. Read: Arthur, W.A. 2009. The Nature of Technology: What it is and How it Evolves, Free Press, New York, Chapter 2 “Combination and Structure,” pp. 27-43. Arthur, W.A. 2009. The Nature of Technology: What it is and How it Evolves, Free Press, New York, Chapter 3 “Phenomena,” pp. 45-67. Questions: How are technologies structured? How do natural phenomena shape the character of technology? How does technology relate to science? Week Two Class #3 – Mon., Feb 3: Origins of technologies This session examines the origins and evolution of new technologies. It examines the mechanisms that lead to the generation of novel technologies and how they are entrenched in social and economic structure. 6 Read: Arthur, W.A. 2009. The Nature of Technology: What it is and How it Evolves, Free Press, New York, Chapter 6 “The Origins of Technologies,” pp. 107-130. Arthur, W.A. 2009. The Nature of Technology: What it is and How it Evolves, Free Press, New York, Chapter 7 “Structural Deepening,” pp. 131-143. Questions: What constitutes novelty in technology? What are the core elements of an invention? How do cumulative inventions shape the direction of the evolution of technology? Class #4– Wed., Feb 5: Co-evolution of technology and economy Technology co-evolves with the economy in the same way that species co-evolve with ecosystems. This session explores the dynamics of this co-evolution and includes discussions of the implications of innovation for the future of the human race. Read: Arthur, W.A. 2009. The Nature of Technology: What it is and How it Evolves, Free Press, New York, Chapter 10 “The Economies Evolving as its Technologies Evolve,” pp. 191202. Arthur, W.A. 2009. The Nature of Technology: What it is and How it Evolves, Free Press, New York, Chapter 11 “Where Do We Stand with This Creation of Ours?” pp. 203-216. Questions: What is the role that technology plays in economic evolution? How does technological innovation shape the economic regeneration? How does technology affect human prospects in the age of ecological awareness? Week Three Class #5 – Mon., Feb 10: Guest Speaker: Disruptive Technologies: Case Studies of Healthcare and Manufacturing Professor Neo-Kok Beng, National University of Singapore Class #6– Wed., Feb 12: Lessons from history: Coffee and tractors [Topic memo due] Fostering the sustainability transition will require the introduction of new technologies, many of which are likely to disruptive and therefore face opposition. Drawing from the historical cases of coffee and farm mechanization, this session examines the key factors that contributed to the emergence of disruptive technologies. It analyzes the patterns of resistance to new technologies by incumbent sectors and concludes with a discussion of the relevance of the lessons to sustainability. Read: Juma, C. Forthcoming. Innovation and its Enemies: Resistance to New Technology, Chapters 2 and 4. 7 Questions: What factors create conditions for the emergence and adoption of disruptive technologies? What tactics are used by incumbent industries to oppose or slow down the adoption of new technologies? What lessons from the cases of coffee and tractors can be applied to innovation for sustainability? Week Four Mon., Feb 17: Presidents’ Day holiday Class #7 - Wed., Feb 19: Lessons from history II: Margarine and recorded music The power of technological incumbency and the associated political forces play an important role in shaping the pace and direction of diffusion of alternative products. This session shows how the dairy and music industries used laws and unions to curtail the spread of new technologies. Read: Juma, C. Forthcoming. Innovation and its Enemies: Resistance to New Technology, Chapters 3 and 7. Questions: What methods were used by incumbent industries to discriminate against new products? What methods were used by the emerging industries to expand their markets? What sustainability-related examples show the same forces against new products? Week Six Class #8 – Mon., Feb. 24: Lessons from history III: Electricity and refrigeration Moments of intense technological competition as associated with efforts to create images that link the product with threats and extreme risks. This session examines how risk perceptions are leveraged as a force in opposing new technologies. Juma, C. Forthcoming. Innovation and its Enemies: Resistance to New Technology, Chapters 5 and 6. Questions: What strategies were to slow down the adoption of AC current and refrigeration? What facts influenced the success of AC current and refrigeration? What contemporary examples from the field of sustainability illustrate the same dynamics as those recorded in the two cases?? Class #9 – Wed., Feb 26: Technology and institutions 8 Technological innovation is associated with adjustments in existing institutional organization arrangements. This session analyzes these co-evolutionary dynamics and lays the groundwork for understanding their policy implications. Read: Nelson, R. and Nelson, K. 2002. “Technology, Institutions, and Innovation Systems,” Research Policy, Vol. 31, No. 2, pp. 265–272. Kemp, R. and Van Lente, H. 2011. “The Dual Challenge of Sustainability Transitions,” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, Vol. 1, No.1, pp. 121-124. Questions: What are institutions and how do they differ from organizations? How do institutions hinder or facilitate technological innovation? What examples from daily life illustrate the links between technology and institutions? Week Five Class #10 – Mon., March 3: Class presentations UNIT 2: RESISTANCE TO GREEN TECHNOLOGIES Building on the foundations laid in the first unit, this unit analyzes examples of contemporary efforts to use technology to solve sustainability challenges. It reviews economic and political forces that stand in the way of integrating new technologies into incumbent industries. Class #11 – Wed., March 5: International diffusion of agricultural biotechnology Advances in molecular biology and related fields have helped to create new products that are widely used in agriculture. This session reviews the state of the knowledge in the adoption of transgenic crops in agriculture. Read: Vanloqueren, G. and P. Baret, P. 2008. “Analysis: Why are Ecological, Low-Input, Multi-Resistant Wheat Cultivars Slow to Develop Commercially? A Belgian Agricultural ‘Lock-In’ Case Study,” Ecological Economics, Vol. 66, No. 2-3, pp. 436-446. James, C. 2013. Global Status of Commercialized Biotech/GM Crops: 2013. International Service for the Acquisition of Agri-biotech Applications, Ithaca, NY, USA (Executive Summary). Kuntz, M. 2012. “Destruction of Public and Governmental Experiments of GMO in Europe,” GM Crops and Food, Vol. 3, No. 4, pp. 1-17. Questions: 9 What factors explain the relatively slow adoption rate of agricultural technologies? What factors have influenced the pace of the adoption of transgenic crops? What role does vandalism play in the adoption of transgenic crops? Week Seven Class #12 – Mon., March 10: Pest-resistant crops The adoption of pest-resistant transgenic crops has been associated with a reduction in the use of harmful pesticides. Despite these ecological and human health benefits, there has been growing criticism of the crops. This session examines trends in the adoption of pest-resistant crops as well as the associated controversies. It outlines the key benefits as well as concerns. Read: Kouser, S, and Qaim, M. 2011. “Impact of Bt Cotton on Pesticide Poisoning in Smallholder Agriculture: A Panel Data Analysis,” Ecological Economics, Vol. 70, No. 11, pp. 2105-2113. Jonas Kathage, J. and Qaim, M. 2012. “Economic Impacts and Impact Dynamics of Bt (Bacillus thuringiensis) Cotton in India,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Vol. 109, No. 29, pp. 11652-11656. Questions: What factors have contributed to the rapid adoption of pest-resistant transgenic crops? What are the socio-economic and health concerns and benefits of pest-resistant crops? What strategies can be adopted to address the concerns? Class #13 – Wed., March 12: Transgenic fish [Extended outline due] The growing demand for fish and the decline of fisheries stocks due to overfishing has emerged as one of the most urgent themes in marine conservation. Fish engineered for fast growth and disease resistance provide a possible option for addressing environmental challenges associated with fisheries. This session examines the environmental benefits and risks as well as regulatory issues associated with transgenic fish. Read: Le Curieux-Belfonda, O. 2009. “Factors to Consider Before Production and Commercialization of Aquatic Genetically Modified Organisms: The Case of Transgenic Salmon,” Environmental Science and Policy, Vol. 12, No. 2, pp. 170-189. Van Eenennaam, A. and Muir, W. 2011. “Transgenic Salmon: A final Leap to the Grocery Shelf?” Nature Biotechnology, Vol. 29, No. 8, pp. 706–710. Questions: What is the current global status of fisheries? How can transgenic fish help to reduce pressure on natural fish stocks? What are the socio-economic sources of concern over transgenic fish? SPRING BREAK: March 15-23 10 Week Eight Class #14 – Mon., March 24: Energy Policy in MA Guest Speaker: Mark Sylvia Wind energy has demonstrated one of the fastest growth rates among renewable energy sources. This has been heralded as a major success in the sustainability transition. This growth, however, has been associated with major public opposition around the world. This session examines the economic and political sources of such resistance. Read: Pidgeon, N. and Demski, C. 2012. “From Nuclear Power to Renewable: Energy System Transformation and Public Attitudes,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, Vol. 68, No. 4, pp. 41-51. Phadke, R. 2011. “Resisting and Reconciling Big Wind: Middle Landscape Politics in the New American West,” Antipode, Vol. 43, No. 3, pp. 754-776. Questions: What is the global status of wind energy adoption worldwide? What is the potential role of wind energy is the sustainability transition? What are the sources of opposition to wind energy and how they be addressed? Class #15– Wed., March 26: Transgenic trees Biotechnology offers a wide range of techniques for forest management, ranging from pest control to environmental management in the timber industry. However, the application of these techniques faces challenges that are similar to those encountered in the GM food sector. This session examines the benefits and risks associated with forest biotechnology and identify policy options for action. Read: Groover, A. 2007. “Will Genomics Guide a Greener Forest Biotech?” Trends in Plant Science, Vol. 12, No. 6, pp. 234-238. Strauss, S.H. et al. 2009. “Strangled at Birth? Forest Biotech and the Convention on Biological Diversity,” Nature Biotechnology, Vol. 27, No. 6, pp. 519-527. Questions: What is the global status of forest resources? What is potential role of transgenic trees in sustainable forestry? What are main sources of concern over transgenic trees? Week Nine Class #16 – Mon., March 31: International Whaling Commission Court Decision 11 Class #17 – Wed., April 2: Biofuels [NO CLASS] The production of biofuels to replace fossil energy has emerged as one of the most elaborate efforts to make the transition toward biological processes. The aim of this session is to examine the sources of controversies in the biofuels sector and outline options for addressing them. Read: Hall, J. et al. 2009. “Brazilian Biofuels and Social Exclusion: Established and Concentrated Ethanol versus Emerging and Dispersed Biodiesel,” Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 17, Supp. 1, pp. S77-S85. Philip Boucher, P. 2012. “The Role of Controversy, Regulation and Engineering in UK Biofuel Development,” Energy Policy, Vol. 42, pp. 148-154. Questions: What is the potential role of biofuels in address sustainability challenges? What are the key advances in biofuels that can address sustainability challenges? What are the main sources of concern over biofuels? Week Ten Class #18– Mon., April 7: Disruption Guest Speaker: Karl Ulrich, Vice Dean of Innovation, The Wharton School UNIT 3: POLICY AND INSTITUTIONAL IMPLICATIONS This unit examines the regulatory principles that govern the integration of new technologies in socio-economic systems. It focuses on the policy implications of such principles and outlines strategies for addressing the associated political challenges. Emphasis is placed on the importance of science and technology policy analysis. Class #19 – Wed., April 9: “Precautionary Principle” and innovation Guest Speaker: Rebecca Connolly Concern over the unintended consequences of new technologies has resulted in the development of new concepts that demand that prior evidence of safety be provided before new products are commercialized. This session examines the history and evolution of the “precautionary principle” and of the balance of evidence on the safety of transgenic crops. Read: Turvey, C. and Mojduszka, E. 2005. “The Precautionary Principle and the Law of Unintended Consequences,” Food Policy, Vol. 30, No. 2, pp. 145-161. 12 Snell, C. et al. 2012. “Assessment of the Health Impact of GM Plant Diets in Long-term and Multigenerational Animal Feeding Trials: A Literature Review,” Food and Chemical Toxicology, Vol 50, Nos. 3-4, pp. 34-48. Brookes, G. and Barfoot, P. 2010. “Global Impact of Biotech Crops: Environmental Effects, 1996-2008,”AgBioForum, Vol. 13, No. 1, pp. 76-94. Questions: What are the elements and origins of the precautionary principle? What is the balance of evidence on the safety of transgenic crops? What are the implications of the precautionary principle for innovation and sustainability? Week Eleven Class #20 – Mon., April 14: No Class--Writing break [First draft due] Class #21 – Wed., April 16: Biosafety, public controversy and the media Guest Speaker: Keith Kloor Transgenic crops have been in commercial use for 18 years. A wide range of studies have been undertaken to assess their environmental and health impacts. However, public controversies continue to rage over transgenic products. This session examines the nature of the controversies, with specific reference to the role of the media. Read: Nicolia, A. 2013. “An Overview of the Last 10 Years of Genetically Engineered Crop Safety Research,” Critical Reviews in Biotechnology. Kloor, K. 2014. “The GMO-Suicide Myth,” Issues In Science and Technology 30(2). Questions: What is the balance of evidence on biosafety research over the last decade? What role do the media play in controversies surrounding transgenic crops? How can the media play a constructive role in shaping public perceptions on the risks of new technologies? Week Twelve Class #22 – Mon., April 21: From niche markets to techno-economic paradigms shifts Guest Speaker: Kathy Araujo Deploying existing technologies and developing new ones is essential for addressing the sustainability challenge. The main policy task is moving niche markets to the creation of large- 13 scale techno-economic paradigms. This session review policy approaches that can help foster such transitions. Read: Nill, J. and Kemp, R. 2009. “Evolutionary Approaches for Sustainable Innovation Policies: From Niche to Paradigm?” Research Policy, Vol. 38, No. 4, pp. 668-680. Yarime, M. 2009. “Public Coordination for Escaping from Technological Lock-in: Its Possibilities and Limits in Replacing Diesel Vehicles with Compressed Natural Gas Vehicles in Tokyo,” Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 17, No. 14, pp. 1281-1288. Questions: What role does advancement in technology play in the transition to a low-carbon economy? What are the key limits the transition from niche markets to techno-economic paradigms? What are the main institutional obstacles to such shifts and how can they be overcome? Class #23 – Wed., April 23: Science and technology advice Science and technology advice is an essential input into the process of public debate over biotechnology. This session reviews the principles, procedures and institutional arrangement used to provide science and technology advice to leaders. Read: Cameron, N. and Caplan, A. 2009. “Our Synthetic Future,” Nature Biotechnology, Vol. 27, No. 12, pp. 1103-1105. Feuer, M. and Maranto, C. 2010. “Science Advice as Procedural Rationality: Reflections on the National Research Council, Minerva, Vol. 48, No. 3, pp. 257-275. Questions: What mechanisms do governments use to secure expert advice on sustainability? What factors influence the success or failure of such mechanisms? What is the role of the general public in the generation and provision of expert advice? Week Thirteen Class #24 - Mon., April 28: Science and technology diplomacy International cooperation is critical to finding solutions to the sustainability challenge. But much of the diplomatic work on sustainability is carried out with limited consideration of the role of technology in development in general and in international relations in particular. This session examines the extent to which emerging diplomatic coalitions such as Brazil, Russian, India, China and South Africa can contribute to new forms of technology cooperation that can support the sustainability transition. Read: 14 Papa, M. and Gleason, N. 2012. “Major Emerging Powers in Sustainable Development Diplomacy: Assessing their Leadership Potential,” Global Environmental Change, Vol. 22, No. 4, October 2012, pp. 915-924. Kera, D. Forthcoming. “Innovation Regimes Based on Collaborative and Global Tinkering: Synthetic Biology and Nanotechnology in the Hackerspaces,” Technology in Society. Questions: How does global competitiveness affect international technology cooperation? How do international trade rules affect international technology cooperation? What alternative approaches can be used to foster international technology cooperation? Class #25 – Wed., April 30: Wrap-up Final papers due: Friday, May 9 Additional Material Innovation and sustainability transition The sustainability challenge represents one of the most complex contemporary policy issues. Much of the early concern over ecological degradation focused on ecological impacts of technological change. This session provides conceptual foundations for exploring the role of innovation in sustainability. Read: Jacobsson, S. and Bergek, A. 2011. “Innovation System Analyses and Sustainability Transitions: Contributions and Suggestions for Research,” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, Vol. 1, No.1, pp. 41-57. Smith, A. et al. 2010. “Innovation Studies and Sustainability Transitions: The Allure of the Multi-Level Perspective and its Challenges,” Research Policy, Vol. 39, No.4, pp. 435-448. Questions: What are the essential attributes of the innovation systems analysis? What makes the innovation systems approach relevant to understanding sustainability transitions? What are the limits of applying the innovation systems approach to sustainability? 15