HEALING THE SCAR_ReadOnly

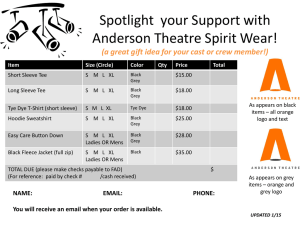

advertisement

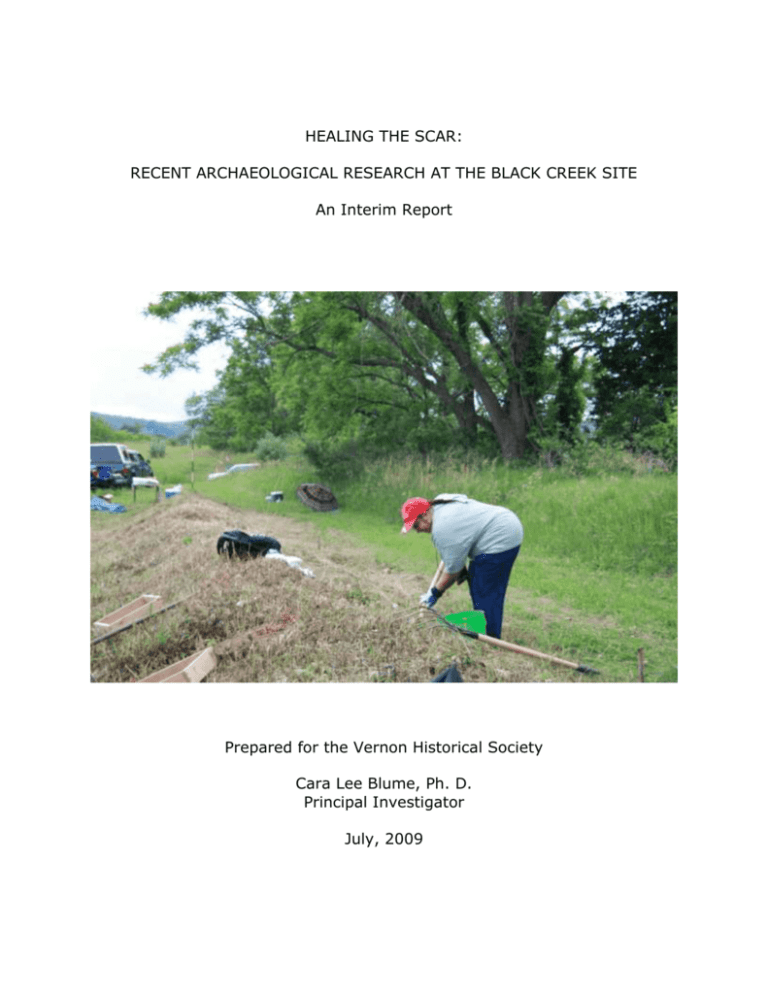

HEALING THE SCAR: RECENT ARCHAEOLOGICAL RESEARCH AT THE BLACK CREEK SITE An Interim Report Prepared for the Vernon Historical Society Cara Lee Blume, Ph. D. Principal Investigator July, 2009 HEALING THE SCAR: RECENT ARCHAEOLOGICAL RESEARCH AT THE BLACK CREEK SITE An Interim Report Cara Lee Blume, Ph. D. Principal Investigator Beginnings Society, the authorized Friends group for Waywayanda State Park, proposed to level the berm and fill the trench in order to restore the appearance of the site. They felt that this project could be used to teach archaeological principles by sifting the soil to remove any artifacts before returning the soil to the trench. Middle and high school students would be invited to participate. The Society asked me to lead the project. I had served as primary archaeological consultant in the legal effort to preserve the site, representing the Nanticoke Lenni-Lenape tribe. Early on the morning of May 23, 2001, Vernon Township sent a bulldozer to cut a shallow trench across the Black Creek Site, an American Indian settlement that had been repeatedly occupied over some 8,000 years--just two hours before a court hearing on an injunction to prevent any construction on the site. The bulldozer also left a berm about two feet high parallel to the trench. Both the berm and the trench paralleled a dry-laid stone wall and hedgerow that separated two cultivated fields. Thanks to the efforts of the Vernon Historical Society and other local citizens and to the involvement of the New Jersey state-recognized Nanticoke Lenni-Lenape tribe, the Black Creek Site was saved from destruction. It has been listed on the New Jersey and National Registers of Historic Places, and is now part of Waywayanda State Park. But the scar left by the bulldozer has remained. After consulting with the Nanticoke Lenni-Lenape tribal council, I agreed to serve as principal investigator. The tribal council and I agreed that the excavation of the berm was acceptable because the soil had been disturbed by the bulldozer, but that excavation elsewhere in this protected site would not be reasonable. We also agreed that the project should be conducted in a manner that would recover as much archaeological information as possible. Finally, we agreed that the tribe’s New As part of an educational program funded by a grant from The History Channel, the Vernon Historical 1 Dawn youth group would be invited to participate. the more finished or heavily used tools collected by Patterson but also the firecracked rock and stone debris, we would have a more complete picture of activities at the site. What We Did and Why The southern part of the Black Creek Site, where the trench and berm were located, had been extensively studied by avocational archaeologist Rick Patterson through a technique called controlled surface collection, in which artifacts recovered from cultivated fields were plotted on maps. The mapped artifacts included tools such as projectile points and scrapers, fragments of pottery and a variety of battered stone tools. But other indications of activities at the site, including firecracked rock from fire hearths and debris from making flaked stone tools, were not collected or mapped, largely as a practical matter. The maps produced from Patterson’s data (see Appendix A) showed that few artifacts were recovered from the precise location of the trench, though there is a concentration just west of the southern end of the trench. Thus, any information recovered from the berm would contribute to our overall understanding of how people lived at the site in the past. The first excavation of the berm was scheduled for the weekend of August 1-2, 2008. The participants on Saturday included high school and middle school students from the local area as well as a group of home school students, assisted by members of the Vernon Historical Society and other citizens of Vernon and Sussex County. We returned with few Society members on August 23 to complete the excavation of sections not completed earlier. We cut half-meter wide sections through the berm at five-meter intervals along a 100-meter baseline that paralleled the berm. The starting point of the baseline was approximately 20 meters north of the beginning of the berm, which ended at about 90 meters. Over this weekend and a second weekend later that month, ten narrow sections were cut through the berm, providing a 10% sample from about half of the berm. A comparison of the artifacts recovered from each of these sections indicated that it was indeed possible to discern quantitative and qualitative differences along the length of the berm. Because the bulldozer had pushed the soil to the side of the trench into a berm paralleling the trench in the same manner as a road grader or snow plow, I concluded that it was likely that gross differences in the distribution of artifacts from one end of the trench to the other could be discerned by excavating the berm itself in controlled increments. If we recovered not only 2 through the berm. This was done to standardize the width of the sections, some of which were narrower than a half-meter and others wider. The wider sections are also easier for untrained participants to work in. Finally, the use of the narrower sections seemed to imply a level of clarity in the distribution of artifacts that is not likely to exist in deposits that have been first cultivated for many years and then scraped to the side. In future excavations, the meter-wide sections will be used. On May 9, 2009, archaeologist Bill Sandy led a group of students from Chatham High School in excavating part of the northern end of the berm. Sandy’s approach was somewhat different from that established previously but nonetheless produced information that will be useful in the final analysis of the artifacts from the berm. Sandy and the group from Chatham High School excavated the western half of the northern 4 meters of the berm as a single unit. The eastern half remains unexcavated, and will be excavated at a later date in one-meter sections. Finally, on June 27 and 28, 17 members of the Nanticoke LenniLenape tribe worked at the site under my direction. The participants included seven members of the tribe’s New Dawn youth group, five members of the Little Acorns group for younger children and six adult leaders. Members of the Vernon Historical Society also participated, as did one of the students who participated in the first excavation period. What We Found When archaeologists excavate sites, they are looking for evidence of the lives of the people who lived there, primarily in the form of artifacts— objects that have been deliberately created or that have been modified through use by human beings. The artifacts recovered from the berm tell us about some of the activities that took place in a small area of the Black Creek Site. I have included a complete inventory of these artifacts in Appendix During this latest excavation period, we widened, to one meter, six of the sections previously excavated 3 B. We can assume that these activities also took place elsewhere in the 40 acres that encompass the site, but the artifacts we have recovered speak most directly to this small area. meters of the berm, and from the sections at 55-56 meters south, 60-61 meters south and from 70-71 meters south. Projectile points are particularly useful for archaeologists because the styles change over time. For instance, the projectile point on the far right of the photograph below is a broken triangular point, dating to the Late Woodland Period, from about AD 700 to AD 1600. The remaining points date to the Middle to Late Archaic Period, from about 4500 BC to about 2000 BC. In general, the artifacts we have recovered tell us about obtaining the food, medicines, and other raw materials needed for daily life, and about how those raw materials were processed for use. Even the debris from making stone tools or from the stones used to build fire hearths can tell us about some of the activities at the site. Other objects we find may tell us about less tangible aspects of life, including art and spirituality. We must always remember, however, that what we find in the ground represents only a small part of the material culture—the things people need to live their lives—that once existed at the Black Creek Site. Many more objects, made of wood, bone, fabric, feathers, animal skins and hair, have disappeared along with the remains of the plants used for food, medicines, flavorings and fibers. What survives are the stone tools, ceramics and other objects that have resisted the decay promoted by the region’s moderate climate. The two crude knives recovered from the berm, one from the northern four meters and one from the section at 70-71 meters south, may also have been used to procure a variety of resources, though it is not clear precisely how they were used. Perhaps they were used to cut grasses or herbaceous plants. Procurement Tools: The only definitive procurement tools we have recovered from the berm excavations at the Black Creek Site are classified as projectile points—used on spears or arrows for hunting. Four projectile points were found in the excavations, from the west half of the northern 4 4 Processing Tools: Processing tools were used to prepare foods or to create finished products from raw materials. The most frequent processing tools found to date in the berm excavations are pitted stones. These are flattish cobbles of a dense material such as quartzite that have depressions on one or both sides. They are often interpreted as having been used in breaking up nuts such as hickory nuts or in supporting chert or jasper blocks that are being roughly shaped before being made into more finished tools. Four pitted stones have been recovered to date in the berm excavations, one each from sections at 55-56 meters south and 60-61 meters south and two fragments from section 65-66 meters south. Several of these pitted stones also showed evidence of use as hammerstones, perhaps for breaking up bone to obtain fragments that could be made into bone tools. A more rounded granitic cobble from section 65-66 meters south also showed signs of use as a hammerstone, as did a broken pebble from the same section. This smaller hammerstone was likely used in the manufacture of projectile points and other chipped stone tools. The smallest processing tools recovered from these excavations include five unifacial flake scrapers. Four of these tools, consisting simply of thin chert flakes that have been lightly used as cutting or scraping tools, were found in the northernmost four meters of the berm. A fifth grey chert scraper recovered from section 35-36 meters south showed signs of resharpening, indicating longer use for a specific purpose, perhaps woodcarving. 5 Debris: Archaeologists find that the amounts of various kinds of debris can be useful in defining activity areas of a site or in understanding the intensity with which certain areas of a site are used. Typically we look at the debris left from making flaked stone tools such as projectile points or scrapers or at fire-cracked or thermally altered rocks from fire hearths or roasting beds. Both flaking debris and fire-cracked rock fragments have been recovered from the berm. Fire cracked rock fragments have also been recovered from the berm. These fragments can generally be recognized by angular breaks and sometimes by a reddish coloration. The majority of the chert and jasper flakes recovered from the berm sections excavated to date come primarily from the final stages of producing a projectile point or other tool. The figures presented in the table below indicates that the greatest intensity of occupation in this part of the Black Creek Site is found at the south end of the berm between the section 5051 meters south and 65-66 meters south. Section Fire-cracked 6 Flakes Other debris rock North 4 meters, west half 25-26 meters south 30-31 meters south 35-36 meters south 40-41 meters south 45-46 meters south 50-51 meters south 55-56 meters south 60-61 meters south 65-66 meters south 70-71 meters south 4 12 1 7 4 9 6 13 9 0 7 21 (5/meter) 4 15 5 17 15 20 5 14 28 6 6 (1.5/meter) 2 2 1 2 4 2 5 2 1 Other objects: We have recovered other kinds of objects from the berm that cannot be described as artifacts because they have not been modified by human activity. However, they may have been selected and brought to the site for various reasons— because the object is interesting, attractive or a reminder of some story or event of significance to the individual or for other reasons. These objects, sometimes dismissively referred to as “ecofacts,” are often disregarded by archaeologists as of no interest or meaning. However, to my mind these objects may be of particular interest as indicators of the creative or spiritual life of the community. berm deposits, but this is the only one with such inclusions. Summing Up The excavations we have conducted so far to remove the berm and fill the trench created by Vernon Township in 2001 have demonstrated that it is possible to discern variations in artifact distributions related to the occupation of the Black Creek Site. Furthermore, this is a useful way to teach archaeological principles to students and other non-professionals without destroying intact archaeological deposits in this protected site. Much work remains to be accomplished, but we can complete the project over the next several years with the assistance of the groups who have already demonstrated a commitment to interpreting and preserving this important site. Three such objects have been found so far in the berm excavations. One is a clear quartz crystal recovered from section 25-26 meters south. Other quartz crystals have been recovered from the site, and it is possible that they come from geodes found in the dolomite of the ridges forming the north and south boundaries of the site. The second object is a piece of a fossil crinoid stem recovered from section 5051 meters south. Crinoids are animals related to starfish that live attached to the sea floor by a hollow calcareous stem. They are found in geological strata as old as 500 million years, as well as in modern oceans. Crinoid stem fragments have been found at other archaeological sites and may have been used as beads. The third object is a black chert pebble with quartz inclusions that resemble fossils, found in section 70-71 meters south. Plain black chert pebbles have been found in the 8 APPENDIX A BLACK CREEK SITE ARTIFACT DISTRIBUTIONS 9 APPENDIX B Artifact Inventory Black Creek Site 28-Sx-297 Note: black flakes are likely from material obtained at the nearby Ring Quarry. Surface 1 black chert flake 20-25 m. south, west half 4 2 1 3 2 2 3 11 chunks, black chert chunks, quartz primary flake, unidentified material flakes, unidentified material flakes, red jasper flakes, grey/black mottled chert flakes, grey chert flakes, black chert 1 1 1 1 1 1 grey/black chert flake, utilized grey chert flake, utilized black chert chunk, utilized grey chert primary flake, utilized argillite knife grey chert triangular point, tip broken 1 1 1 1 nut/bolt fragment plastic pigeon frag., “BLU” clear window glass fragment limestone frag. 25-26 m. south (partial) 4 1 1 fire-cracked rock fragments grey chert primary flake mottled grey chert flake 10 1 1 black chert flake red jasper flake, possibly heat-treated 1 clear quartz crystal 1 1 pale green window glass fragment coal fragment 30-31 m. south (partial) 12 2 1 4 6 1 1 2 1 fire-cracked rock fragments black chert chunks grey chert primary flake black chert flakes grey chert flakes brown jasper flakes grey/brown chert flake flakes, unidentified material hammerstone fragment 2 1 clear bottle glass fragments agricultural lime fragment 35-36 m. south (partial) 1 2 1 1 1 2 1 1 1 fire-cracked rock fragment black chert chunks mottled grey/black chert flake mottled grey flake grey chert flake dark brown jasper flakes grey chert flake scraper hammerstone fragment hammerstone 40-41 m. south (partial) 7 1 1 9 fire-cracked rock fragments quartz cobble/core red jasper flake black chert flakes 11 3 4 grey chert flake mottled grey/black chert flakes 45-46 m. south 4 2 1 1 1 1 1 3 8 1 2 fire-cracked rock fragments black chert chunks mottled grey/black chert chunk white quartz chunk primary banded grey/black chert flake with cortex at both ends— possibly Ring Quarry material primary grey chert flake banded grey/black chert flake grey chert flakes black chert flakes dark brown jasper flake brown flakes of a slatey material 1 small hammerstone 1 partially melted glass fragment 50-51 m. south 9 4 1 15 2 2 fire-cracked rock fragments black chert chunk black chert primary flake black chert flakes grey chert flakes red chert flakes 1 crinoid stem fragment 1 annular whiteware rimsherd 55-56 m. south 6 2 3 1 fire-cracked rock fragments black chert chunks black chert flakes grey/black mottled chert flake 12 1 cream-colored chert flake 1 1 small black chert notched projectile point bi-pitted stone 1 iron strap fragment 60-61 m. south 13 5 2 1 2 4 1 4 1 1 1 fire-cracked rock fragments black chert chunks black chert flakes grey/black banded chert chunk grey/black mottled chert flakes grey chert flakes cream-colored chalcedony flake flakes black unidentified slatey material grey chert stemmed projectile point (Lackawaxen) battered cobble with slight pit on one surface possible pendant fragment 65-66 m. south 8 1 2 14 2 1 7 2 2 fire-cracked rock fragments fire-cracked rock fragment that may have been part of a mortar black chert chunks black chert flakes grey/black chert flakes light grey chert primary flake grey chert flakes cream-colored chert flakes flakes of unidentified slatey material 1 1 1 1 small pebble hammerstone granitic cobble hammerstone battered cobble with two pits on one surface broken cobble with pits on opposite surfaces 1 whiteware sherd 13 70-71 m. south 1 2 3 1 black chert chunk flakes unidentified slatey material, one with pink inclusions black chert flakes brown jasper flake 1 1 1 crude knife, unidentified material black chert pebble with quartz inclusions that may be fossils grey chert stemmed projectile point (Lackawaxen) 14