- Ethiopia education

advertisement

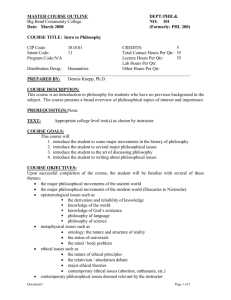

Six stories in search of a character? ‘The philosopher’ in an educational research group David Bridges with notes in response by Maggie MacLure Centre for Applied Research in Education University of East Anglia Norwich, NR4 7TJ d.bridges@uea.ac.uk Introduction1 The challenge of the topic itself says something about the relationship of the philosopher (I shall leave the problematisation of this label till later) to the empirical and applied domain. How does one engage philosophically with a topic like this. How if at all can one write philosophically about ‘a research group’ or even the idea of a research group? When I first entered philosophy of education and received my training in the predominantly analytic tradition at the London Institute of Education I would have jumped straight in with an analysis of the concept of research and of the concept of a group and might have suggested that given these analyses a research group had to have certain features. I might have extended this more boldly (and I suspect unanalytically) to suggest some ways in which a research group needed to function. Peters was not the only one to fall foul of the accusation of extracting prescriptions for what one should do from analysis of the meanings of words. I do not propose to go down this path, though enough of this tradition is embedded in me to lead me to offer at least these thoughts. In the field of (educational) research we refer to research teams, research groups and research centres. These have in common the features of (i) bringing together of a number of researchers in some formation; (ii) around some common task or set of tasks; and, perhaps (iii) with some shared principles, values or interests. They differ perhaps in terms of their relative stability or permanence (research teams being perhaps the least permanent and centres the most) and in terms of their institutionalisation and possibly their organisational infrastructure. The things which they have in common seem to me to be more significant and interesting than the things which differentiate them, and this is my excuse (a very un-analytic turn here) for largely ignoring the differences and for illustrating this discussion from examples of research groupings that include temporary teams, more longstanding groups and, in one instance, a long established research centre. In the main part of this paper I shall explore my own experience of six such groupings and reflect on the different roles which ‘the philosopher’ has played in their work. We need, nevertheless to be alert to what seems to me to be a programmatic attempt to impose not only a particular discourse but, with this, particular patterns of organisation on the educational and more broadly social scientific research community. The language of ‘the research group’ is a very familiar one in the natural science research community, in which it is attached to a particular scale of research projects (often associated with considerable investment in capital equipment), the prospect of at least medium term continuation of funding, and a particular organisational structure with clearly segmented division of labour. These same features have been the exceptions rather than the rule in the field of educational research and, I would have thought, very rare indeed in the field of philosophy. One response to this observation has been to suggest or suppose that educational research would be more productive or effective if it was organised in something closer to this natural science pattern. There has been considerable debate in the UK prompted by the apparent expectation of those responsible for the Higher Education Funding Council (HEFC) Research Assessment Exercise that university research would be presented to it in the form of research groups and that the primary unit of assessment of quality would be these groups. The judgement of the quality of the work of a department would then be made in terms of the balance of the quality of the work of the different research groups (taking size as well as quality into account). HEFC offered at one stage the reassurance that a research group might consist of just one researcher (this presumably from someone without benefit of training in analytic philosophy) but this has done little to allay the suspicion that the research group, on something like the model of the natural science research group, is the form of research organisation which is preferred and will be rewarded. It is worth considering the implications of such a position. What are the consequences for research – what voices get suppressed and what voices get promoted – if the research group becomes the preferred or even the required form for its organisation? With this caution, let me turn to the particular examples, the sites of practice, to see what they might reveal about the role of the philosopher in an educational research group. 1 This paper is a revised version of one originally presented to the international symposium on Philosophy and History of the Discipline of Education at the Catholic University of Leuven th th 6 -8 November 2002 in response to an invitation to write about ‘the research group’. My CARE colleague, Maggie MacLure wrote a short response to this original draft, and I have incorporated her main comments as footnotes to this version.. 2 The ‘Cambridge Group’ of philosophers of education I have only once belonged to something which self-consciously and perhaps with excessive vanity referred to itself and was referred to as in research terms as a group (though at that time we thought of ourselves a doing philosophy rather than doing research). In a recent piece of autobiographical writing (Bridges 2003) I recalled it in these terms: The London Institute experience was important, but increasingly Cambridge provided its own intellectual stimulus, because Richard Pring and Hugh Sockett had come to the Cambridge Institute of Education as research fellows and Peter Scrimshaw had joined Charles Bailey and myself at Homerton. John Elliott, initially working on the Humanities Curriculum Project, was also living in Cambridge – and we were all working on higher degrees in philosophy of education. We would meet for seminars, food and wine in each others’ houses and all travel to the London seminars in Hugh Sockett’s minibus – usually to be confirmed in our belief that our own seminars, including those conducted in the minibus and the pub off the A1 on the way home, were superior in style and content to those that we encountered at the Institute. With growing selfconfidence we concluded after a visit to Dillons bookshop that we could write rubbish no worse than that which we found on the shelves there, and the ‘Cambridge Group’, as we came to think of ourselves, contracted with Hodder and Stoughton for a series of books on philosophy of education (Elliott and Pring 1975, Bridges and Scrimshaw 1975, Sockett 1979). Paul Hirst moved from London to join us at the Cambridge Department of Education, soon to be joined by Terry McLaughlin and at Homerton by Mike Bonnett, and was hugely supportive to our own initiatives and became part of an increasingly strong and capable team2. It may be useful to consider what were the features of this group of people which even began to prompt it to think about itself as a Group in the research sense. It had at least the following features: a number of people talking, for all the differences between us, a broadly similar academic language (provided very largely by our shared experience at the hands of Peters, Hirst et al at the London Institute); physical and social proximity (perhaps less important today than it was then); reciprocity of interest and mutual support in pursuing individual objectives (notably in the pursuit of higher degrees); a succession of common projects (notably in publishing and in the development of philosophy of education in Cambridge); a sense of our difference from others – notably in this case the main base of philosophy of education at the London Institute. Rightly or wrongly we saw ourselves as much more closely aligned with contemporary debates and development around the school curriculum. Hence our decision to seek a publisher for our books other than Routledge and Kegan Paul that Peters would have had us turn to. We also self-consciously adopted a different mode of discussion to the sharply antagonistic mode fashionable in London. When one of us read a paper, each of the others would first and in turn try to suggest ways in which it could be developed, extended or improved, before we got into more critical debate. What is interesting in terms of the comparison with the scientific model of the research group is that we had no formal structure to support this group, no funding, and it operated without a hierarchy or with several hierarchies, because we were in the happy position of acknowledging the different strengths of individual members of the group even this did not entirely prevent an element of competition between us. This was the late sixties and early seventies and the Socketts, Elliotts and Bridges seriously contemplated for a time the prospect of living in a commune together. This does not however appear to be a necessary requirement for those seeking to form a research group and , wisely I suspect, we decided to pursue our separate domestic lives. The self-consciousness with which we sought to maintain a non-hierarchical group and our flirtation with the idea of communal living do however prompt two sets of questions of a philosophical kind. First, it is worth considering what sort of social organisation is required for the successful operation of a research group. Were our instincts right in seeking something non-hierarchical – is this something to do with ‘the management of talent’ as it is sometimes expressed? Or was this simply a fashionable seventies fantasy? And is this question one which essentially requires an empirically grounded answer There is some triangulation of this story, with John Elliott’s chapter ‘Institutions of the mind: autobiographical fragments’ (Elliott 1998) originally presented as a paper to the BERA/SERA symposium organised by Eileen Francis. 2 3 (experience and observation indicate that specified conditions produce certain observable effects) or is it possible to derive a view of the required social organisation or social philosophy of a research group from eg an understanding of the nature of research? Secondly, it is worth considering what are the ethical obligations which people owe towards each other when they are working in a research group. I read as I was writing the first draft of this paper in the Times Higher Education Supplement (4th October 2002 p7) commentary on the aftermath of the ‘Bell Labs research fraud scandal’ in which a distinguished scientist was found to have been engaged in widespread data fabrication. The Times correspondent, Steve Farrar wrote) with reference to the report of the independent investigative committee: ‘It asked whether Dr Batlogg, the widely respected leader of Dr Schon’s research group and co-author of many of its papers. “took a sufficiently critical stance with regard to the research in question” before explicit doubts were brought to his attention. It concluded that it was unable to resolve some questions in Dr Batlogg’s case “given the absence of a broader consensus on the nature of the responsibilities of participants in collaborative research endeavours.”’ (Farrar 2002: 7.) This extract seems to me to be very pertinent to our discussions of research groups. It suggests: (i) (ii) (iii) that members of research groups do by that membership get drawn into obligations one to another; that the nature of these obligations is not entirely clear; but that they probably include some obligation of critical scrutiny of each other’s work (a fortiori perhaps where one’s name is put to it by virtue of being a member of the group). I would want to add a fourth proposition to these because it seems to me that research groups work under a complimentary obligation of mutual criticism and support: personal and practical support in overcoming difficulties in the research process but also political solidarity when faced with attempts to censor or distort or otherwise undermine the integrity of the outcomes of research and the research process. For the moment, however, the point I want to make here is that a research group is not just a unit for the organisation of research production: it is a group of people locked in a nexus of mutual obligation which are created by the epistemological and social conditions which give it integrity. The ‘Cambridge Group’ was a group made up entirely of philosophers of education – or at least this was the identity which united us. But my main interest in this paper is in exploring questions to do with the role of the philosopher of education in inter-disciplinary or multi-disciplinary research groups. How does one begin to write about this as a philosopher? As I have already illustrated, my instinct is to start with some examples and to reflect on the perspectives and issues which arise from these. My next example will be a project from, again, some years ago: the Farmington Trust Moral Education Project (Wilson, Williams and Sugarman 1967) which, innovatively in those days, brought together a philosopher, a psychologist and a sociologist to propose a way forward for moral education in schools. The philosopher was John Wilson, who subsequently wrote about philosophy and educational research in terms which have led him and me into a quite extended debate (Wilson 1994, Bridges 1997, Wilson 1998 and Bridges 1998. His view, still firmly rooted in conceptual analysis, represents a lot of what I have been reacting against, which is why it provides a convenient starting point. I will go from there to discuss briefly some of the issues raised by three empirically grounded projects, a research centre and a research network in which I have been directly involved. The Farmington Trust Moral Education Project This project was established in the days in which educational theory was increasingly firmly defined in the UK in terms of the foundation disciplines of philosophy, sociology, psychology and history of education. At a time when each of these was emphatically defining itself in terms of its difference and their academic storm-troopers were fiercely defending their territorial boundaries it was quite adventurous to set up and educational research and development project which was structurally interdisciplinary. Wilson (the philosopher) Williams (the psychologist) and Sugarman (the sociologist) 4 had to establish a modus operandi as a research group and in the absence of many very clear precedents. I do not want to get drawn into too much detail about the project here. What is especially pertinent is the role taken by the philosopher. Wilson saw his job (and this was apparently acquiesced in by the others) as to provide the conceptual mapping of the territory, or, to borrow a different metaphor, the conceptual architecture of moral education. Moral education, in his view, could only be articulated upon some understanding of what it was to be moral and of the knowledge understanding and etc which were the components of moral choice and moral action. So his primary task in the group was to analyse these components. (Wilson, Williams and Sugarman 1967). But this conception of the role of the philosopher as conceptual architect has not just remained an historical curiosity.3 As late as the 1994 BERA conference Wilson was still defining philosophy in these narrow conceptual terms: ‘That is all that “philosophy”, in the sense in which I am using the word, requires: it is a practice, a discipline of thought, devoted to getting clear about words and concepts and the logical implications that they carry.’ (Wilson 1994: 4 his underlining) Philosophers are specialists in the task who might act as consultants to researchers proper: ‘There is no real alternative to educational researchers themselves taking on this task… of working out the meaning and concepts with which their research is concerned. Enough philosophers (not just me) are around to help them with this if required: there is certainly some professional expertise here, though most intelligent researchers can do a lot for themselves, once they get the hang of it.’ (ibid p. 6) They were, no doubt, grateful for this reassurance. I can comfortably share the view that a little more care and clarity in the use of language and concepts could benefit a lot of research writing (and indeed some philosophical writing). And indeed the occasional piece of empirical research seems bent on providing little more than an empirical foundation for a tautology. Apart from this, however, Wilson’s view seems to me to be really quite damagingly misleading. First it fails seriously to do justice to the richness of philosophical writing on moral, epistemological and political issues which is of a substantive kind which goes far beyond mere conceptual analysis. Secondly, it is really rather patronising as towards people who do not define themselves as philosophers but who can yet be perfectly clear about language and concepts, in so far as they lend themselves to such clarification. Finally, it ignores (without repudiating) all the literature about language and meaning which renders problematic the idea that there is a simple clarification of the meaning of a word which is to be had. Replying to an earlier presentation of my criticisms (Bridges 1997), Wilson (1998) still seemed to assume that one could establish the meaning of a word without some implicit or explicit theory of meaning itself, or of the function of language in the conveyance (one theory) or construction (another theory) of meaning. I find it surprising that Wilson can propose that ‘Anyone who takes this task (he refers to conceptual analysis) seriously will find himself/herself engaged in a practice which makes no “assumptions” and has no dealings with “theory” or ideology, or any “school of thought” (philosophical or other.)’ (Wilson 1998: 130) Wilson himself seems peculiarly unsure about his approach to meaning given the importance which he attaches to its clarification. At one moment he presents meaning as something to be recalled (quoting Wittgenstein’s suggestion that we ‘assemble reminders’ p. 129); in the next, meaning is something to be decided, perhaps prescribed (p. 130); and then later it looks as if meaning is something to be agreed with other people (p. 130). The history of analytic philosophy of education reflects debate about whether conceptual analysis is to be seen as an essentially empirical investigation of ordinary language usage and the categories which people bring to their experience of the world or whether, as Dunlop asked of Peters some years ago, it involves reflecting on ‘a distinction which is somehow forced upon us by the nature of the world’ (Dunlop 1970. See also on some of the problems of deciding what is actually going on in conceptual analysis: Reddiford 1972, Earwaker 1973, Naish 1984, Walsh 1985.) What is clear is, first, that Wilson cannot have it all ways and, secondly, whatever view he does hold comes heavily laden with theory. Nor does this theory come without its ideological baggage. The processes of defining, prescribing or negotiating the meaning of terms themselves indicate three different kinds of power relations between the ‘analyst’ and other members of the linguistic community. The following discussion of Wilson draws from chapter 3 of my book ‘Fiction written under oath: Essays in philosophy and educational research (Kluwer 2003). 3 5 But if I am not happy with Wilson’s view of the role of the philosopher in the context of educational research and more particularly the philosopher’s contribution to multi-disciplinary research, what are the alternatives? My own excursions into educational research have been opportunist rather than schematic. I entered out of curiosity and without any pre-formed view of how it might work out. So what follows are some retrospective reflections on experience and the issues which this raised. The Social Science Research Council School Accountability Project Between 1979 and 1981 I was a member of a research team working on a research project directed by John Elliott on school accountability. It was constructed around the idea of a self-accounting school, which at the time seemed to offer an alternative model of accountability to the more bureaucratic and centrally driven models which were on the political horizon and of course rapidly came to dominate the political and educational agenda. There were five of us in the team: John Elliott, who had some background in philosophy of education, but was at that time building a significant reputation as one of the main driving forces in the field of action research; Dave Ebbutt who was also extensively involved by then in action research; Rex Gibson, a sociologist; Jennifer Nias, a social psychologist; and myself a philosopher with, as it turned out usefully, a previous incarnation as a historian. The project was, however, unequivocally founded on empirical work, on case studies of six schools (Dave Ebbutt would produce two of these) conducted over an eighteen month period. We would be looking at the way in which these schools, all of which presented themselves as wishing to be accountable to their communities, communicated with and related to parents, governors, local employers, the local press and any other sections of their communities. This would require analysis of documentary evidence, observation of events, participant observation in some events and a wide range of interviews. We each produced substantial case studies based on the material this generated and, out of these, a collection of analytic papers addressing issues raised from reading across the case studies. In one sense my training and my identity as a philosopher was entirely submerged in my role in this group as an apprentice ethnographer. It helped a bit that the head of the school to which I was attached had been a student of mine on a Diploma of Philosophy course, but though this may have given some of our conversations a particular complexion, this was mostly significant in terms of the personal relationship which we had already established. Given that I had very little previous experience and no training in this kind of work, I was largely pre-occupied with the social processes involved in ethnographic research. My most useful resource was my earlier historical training, and the comfort of Lawrence Stenhouse’s notion of research as ‘contemporary history’. I realised that what I was collecting were or would become (eg in the form of transcripts of interviews) a large set of textual or documentary evidence of people’s perceptions of events and relationships. As an historian, I had some idea how to handle such material, though was it as a philosopher that I recognised this sort of epistemological congruity? But no empirical research, least of all this kind of ethnographic research, is theoretically or ideologically neutral: nor did we set out to purge it of such impurities. On the contrary, the field research was conducted in a context of intense political and educational debate about school accountability – debates which were explicit in the schools in which we were working and the conversations which we had with participants. In regular meetings in the research teams, too, we were constantly discussing the issues which were arising out of our individual cases and issues which we might agree to explore more closely in our own studies (ie we allowed ourselves progressive focussing). Inevitably, of course, these discussions in the schools and in the project team were informed by the theoretical and analytic frameworks which each of us brought to the work. We did not necessarily label these with our particular disciplines; nor did we observe rigidly disciplinary boundaries in the ideas and material we referenced (after all each of us drew from quite wide educational training and experience); but inevitably the thinking and analysis was shaped by the theoretical and conceptual frameworks which we could each bring and was, I think, the richer for it. In the analytic papers which came out of the project (Elliott, Bridges, Ebbutt, Gibson and Nias 1981), we could indulge our particular interests more freely. I wrote three of them: ‘It’s the ones who never turn up that you really want to see’: the ‘problem’ of the non-attending parent; Teachers and ‘the world of work’; and Accountability, communication and control. Re-reading these twenty years later 6 (and I had clean forgotten about one of them) I recognise a distinctive philosophical flavour interwoven with the evidential reporting: in the attention given to contrasting views of the purpose of education; in the reference to the moral obligations of teachers to their children; in the interrogation of the discourse about eg an ‘adaptable’ workforce; about the location of ‘the world of work’; in the analysis of the relationship between accountability, communication and control; and most vividly, perhaps, in my ideologically transparent discussion of ‘the rational professional and professional autonomy’. More accurately, it is a flavour which was provided in my life history by my philosophical reading and experience. My problematising of the ‘problem’ of the non-attending parent is something which I might as easily have arrived at through sociological critique or social psychology as through philosophising. These reflections lead me to two observations with which I shall conclude this section. First, and not for the first time (see Bridges 1997 and 1999), I am driven to observe that biographical stories about the forms of enquiry through which people come to particular ideas or hypotheses are not necessarily congruent with the logical stories which we are obliged to construct to provide the ‘proper’ epistemological foundation for such ideas or hypotheses. What I might think or write because of my philosophical background might be something which (in some cases at least) someone else might as easily arrive at from eg their sociological background. Secondly, and by extension, there are a whole variety of intellectual habits, dispositions and indeed virtues which are shared across the academy; there is, especially across the social sciences, an abundance of common literary reference; there are at least overlapping methods and methodologies; and any social science programme worth its salt will take students at least some way into the epistemological and ethical problems underlying its practice and the broader philosophical considerations which inform its continuing evolution. In the course of the study of any one of these disciplines one is likely to encounter a substantial body of literature and thought which is also addressed in another. To identify myself as ‘a philosopher’ may say something about the social route through which I have encountered and developed whatever academic ideas and attributes I have, but it does not necessarily mean that they are sui generis to that subject. Identity as ‘a philosopher’ or ‘a sociologist’ is something which, for many of us working in education, is something imposed on us or selected from a range of possibilities rather than something which reflects the heterogeneity of our intellectual roots and resources. It seems to me to follow from this that we have to question the idea that there is someone present in a research group who can satisfactorily be categorised as ‘the philosopher’ and that ‘the philosopher’ will want to resist such a role. A successful research group (and I regard the Accountability Project as one such) draws in people who import a wide range of experience and thought and who ‘muck in’ with all that they have and borrow freely from each other. I suspect that I may be obliged to qualify this position, but I shall leave it there for the moment as a picture which stands in vivid contrast to the kind of compartmentalised, discipline-based, collaborative research illustrated by the Moral Education Project.4 A multi-disciplinary project on classroom discussion This project brought together a group of some twenty educational researchers at one stage or another in a five year programme of work directed by Jim Dillon of the University of California, Riverside. It culminated in a book published under the title Questioning and discussion: a multi-disciplinary study (Dillon 1988). The idea was an intriguing one. Dillon produced six transcripts of discussion in Your reflections helped me think about the nature of interdisciplinarity. For me, there’s (crudely) a ‘good’ and a ‘bad’ version. The bad one (and the one promoted, I think, by our UK funding bodies) thinks of interdisciplinary research as a coming together of a bunch of ‘characters’ with very distinct (and intact) disciplinary identities – a sociologist, a psychologist, a philosopher etc. The assumption seems to be that new knowledge will emerge as a kind of accumulation (or fusion perhaps) of the perspectives of each individual. But I suspect that when interdisciplinarity does ‘work’, it does so for the reasons that you point to in your discussion of the Cambridge Accountability project. That is, new knowledge emerges when people lose some part of their discrete professional/ occupational identities, in the process of working on some common purpose. 4 I’d go further, and argue that the productive potential of interdisciplinary projects isn’t (or isn’t just) that you provide more ‘angles’ on an issue or problem – but rather, that the various disciplines infect and unsettle one another. So, sociological certainty gets pricked by philosophical challenge; psychological notions of the self get complicated by social or philosophical ones, and so on. Isn’t such a commitment to unsettling itself an instance of (some kind of) philosophical attitude? (Maggie MacLure) 7 American High School classrooms; provided a little (for some, predictably, far too little) information about the context of the discussion; and invited a team of scholars from different disciplinary backgrounds to provide analyses from the perspective of their particular disciplinary or subdisciplinary orientation. Philosophical perspectives of slightly different kinds were provided by C.J.B.Macmillan, William Knitter and myself and Dennis O’Brien also contributed to our discussions, which extended into meta-analysis of the difference between our approaches and of the process of multi-disciplinary inquiry itself. This example raises again for me the question of what a philosopher can do, faced with empirical data – in this case a set of transcripts. The (philosophical) task of course gets easier as soon as we get commentaries from different perspectives upon the data. We can begin to un-pick the methodological or epistemological assumptions underlying the different accounts and interpretations. Of course, to return to the observations at the end of the last section of this paper, so can people who are not philosophers: th discourse analysts, the sociologists of knowledge, the psycho dynamicists etc.. But how does a philosopher deal with the primary data? 5 My response reflected perhaps the over-confidence of we philosophers at that time. Drawing on work I had done for my doctoral thesis (published in Bridges 1979 and 1988), Dillon’s book opened with my chapter which began: ‘This chapter sets out to offer some qualitative criteria by reference to which one might judge whether a classroom discussion had been a good one – and then to apply them to the five examples of classroom discussion offered in James Dillon’s transcripts.” (Dillon 1988 p15). I derived (or claimed to derive) the criteria of quality from an analysis of the functions of discussion in the refinement and enrichment of understanding. In one sense the philosophical work was fairly quickly despatched as I went on to explore the way in which the features of discussion that I had identified were or were not exhibited in the evidence. MacMillan had a slightly more subtle approach, but was essentially engaged in the same task of examining the transcripts against certain criteria. He had developed with Jim Garrison what they called an erotetic concept of teaching (Macmillan and Garrison 1983) which asserts that ‘when a teacher is teaching what he (sic) is doing is attempting to answer the students’ questions about the subject matter.’ (Macmillan 1988 p 90). Knitter had the philosophically more obvious task of providing a meta-analysis of the other analyses (Knitter 1988). MacMillan’s and my own responses to the task set suggest that philosophers may be bolder than some in addressing the quality issues. Our territory includes after all a long history in which scholars have advanced not only substantive views of what merits value or quality in fundamental spheres of human experience but also arguments about the ways in which such views may or may not be derived, of the connection between one set of premises and another set of conclusions etc.. Equally of course philosophers will be savage in their critique of any views of this kind which are advanced or even of the possibility of advancing such views in a way which ultimately avoids the perils of arbitrariness, subjectivity or social relativism. Nor will they be alone is such critique. A plethora of intellectual traditions joins in the postmodern rush to deconstruct (ie substantially to undermine) any ambition for knowledge of the good. So I am left with an empirically grounded report of what two philosophers did, faced with a pile of transcripts of classroom discussion, but without much confidence that I can extract from this any general theory of what the role of the philosopher is (ought to be?) qua philosopher in such circumstances. The Centre for Applied Research in Education All the cases I have illustrated so far are cases of research groups formed temporarily in connection with particular projects, though in all the cases with which I have been concerned these teams have been drawn from or gone on to constitute much more longstanding networks of professional friends ‘How does a philosopher deal with the primary data?’ you ask. Why is there a problem? I detect an old, unchallenged binary opposition here. Is it that transcripts and speech seem ‘spontaneous’, ‘raw’, un-wrought, un-thought – ie self-evident, and therefore (somehow) impervious to philosophical interventions? You write that the analytic task became ‘easier’ once there were commentaries on those transcripts, which then offered up assumptions that could be ‘unpicked’. But isn’t the ‘primary’ data textual too? Can’t it be philosophically ‘unpicked’ to disclose interpretative strategies, or ‘epistemological’ assumptions, or identity claims on the part of the speakers? Or would I be speaking like/as a discourse analyst in making such a suggestion? (Maggie MacLure) 5 8 and colleagues. This next illustration is of a different order. The Centre for Applied Research in Education at the University of East Anglia is one of the longest established educational research centres in the UK, having been established in 1970 by Lawrence Stenhouse on the basis of the team which had been responsible for the development and evaluation of the Humanities Curriculum Project. It established its reputation as the driving force in the UK for the development of action research; for its sophistication of approaches to educational evaluation, notably through MacDonald’s work in ‘democratic evaluation’; through its development and teaching of qualitative methods of enquiry and engagement with methodological issues in educational research. My own association with the Centre goes back to its very early days, though it was not until my appointment to a Chair at UEA in 1990 that I became routinely involved in its work. There is an awful lot which could be said about CARE as a research group whose intense sense of having a unique tradition and identity which set it apart existed side by side with constant division and debate about what that identity consisted in. But I want to refer to this example to make a single point. None of the staff whom I joined in CARE would have identified themselves as philosophers with the exception of John Elliott, who would I think have said something else about himself first. And yet I have rarely encountered a centre in which there was a greater fervent of and enthusiasm for what I would identify as philosophical ideas. It was not that the standard references in philosophy of education were constantly (or ever) on their lips, though Stenhouse always acknowledged a debt to the work of Richard Peters and the European continental sources that inform a lot of contemporary debate about postmodernism as well as older sources in critical theory, phenomenology, feminist theory and hermaneutics found an early embrace in the Centre. Rather it was the constant wrestling with and questioning of the status of research knowledge and of professional knowledge; with problems of inference and generalisability; with what Helen Simons dubbed ‘the science of the singular’ (Simons 1980); with the ethical issues associated with insider and outsider research; with the politics of contract research and issues to do with intellectual property; with the ontology of classrooms and with very nature of education and educational processes. 6 This is not intended as a nostalgic eulogy to CARE, though there is no harm in reminding oneself of the importance of philosophical sources and a philosophical mindset to a centre defined in terms of ‘applied’ research in education. The reason I present the description in these terms is that it requires a different construction of the idea of ; ‘the role of the philosopher in an educational research group’. In one sense it renders ‘the philosopher’ redundant for the best possible reason – because serious and informed engagement with the philosophical issues in educational research is part and parcel of the professional practice of the entire research group. (Though are we prepared to live with this loss of identity?). But as I have argued in other contexts (Bridges 1997), the sad thing has been that this community of discourse has not been adequately joined (in the UK any way) to that other community of discourse populated by people who identify themselves as philosophers of education. They have occupied different journals, attended different conferences, read and referred to different books and only rarely joined in common debate which I believe could only enrich both parties. 7 Philosophically-animated research groups (and CARE’s just one of many) do such things as: question the status of the knowledge and evidence that they produce; reflect on the nature of the ‘self’ and its implication (ie folded-in-ness) in the generation of research knowledge; explore relationships between language (or discourse) and reality; interrogate notions of ethics, democracy, authenticity, authority, experience, generalisation etc. And importantly, they do it routinely, as part of whatever else it is that they also do. 6 I think that, in some respects, the prospects for this kind of philosophically–animated educational research are better now than ever. After all, social and educational research is already ‘infected’ with philosophical ideas. The poststructural or postmodern ‘turn’, as you mention, has involved a blurring of the boundaries between disciplines that previously considered themselves intact and ‘pure’ – literature, philosophy, anthropology, education, psychoanalysis, etc. And philosophy has been central to this dissemination (in Derrida’s sense) of ideas and practices that formerly were (or tried to be) more ‘disciplined’. As you point out, Continental philosophical traditions - hermenuetics, phenomenology, critical theory, existentialism etc – have made a huge contribution to the development of post-paradigmatic ‘Theory’. But this has been at the expense of the former ‘purity’ of those individual traditions. Not everybody thinks this is a good thing, of course. There is continued resistance to the spread of this philosophical/literary/psychoanalytic/ linguistic virus, from those who want to stay more emphatically within the old disciplinary categories. (Maggie MacLure) 7 The kind of inter- (or post-) disciplinary provocation we are both interested her can probably only work amongst members of a discourse community - ie people who, as you suggest, are bound together by ties of history, purpose, custom, loyalty, obligation and a sense of difference and who are also bound together by the kinds of texts they produce, consume and value. As you note, the differences between the putative communities of qualitative researchers and philosophers of education are also, in a fundamental way, textual. Their respective members ‘have occupied different journals, attended different conferences, read and 9 The European Education Research Association (EERA) Philosophy of Education Network and Network Convenors Group. My last example is intended as a reminder of the huge changes which have taken place over the period of 35 years from which these examples have been taken in the way in which, let’s call them research collaborations, can operate. The very language of ‘networks’ has assumed a new significance over this period in indicating groups which are uncontained by any spatio-temporal limitations; groups which are multi-centered and with multiple connections one with another. There is no membership list for the EERA Philosophy of Education Network, though its broadest identity is probably in the people who have asked to be on its e-mail list8 and who consequently receive from time to time notices of conferences, calls for papers, pleas for help, notices about job vacancies and just from time to time a prompt to take part in an e-mail discussion. It also exists for a few days each year as a network programme at the EERA annual conference and corporeally in the presence of overlapping sets of people who attend different sessions in the programme or perhaps the network dinner! More narrowly, the network has five convenors located in five different countries of Europe, who have to correspond more regularly, in particular to arrange the conference programme and to meet occasional demands for the EERA Secretariat. Most recently they have taken to staying at the same hotel for the conference so that they get a little chance to get to know each other and enjoy informal exchange. Some exchange visits and possible research collaborations are beginning to take place out of this activity. By many standards this is a pretty loose group and it has so far had limited outcome in terms of the origination of, as distinct from the presentation of, research. It is a reminder, however, of the ways in which contemporary research groups can operate: across huge geographical divides; in loose knit as well as tightly knit configurations (with ‘lurkers’ as well as active participants); in virtual space and without direct face to face contact; in a multi-layered, multi-media, multi-dimensional learning and research environment (see Burbules and Callister 1999). This is not without its problems however. One of the recurring discussions in the EERA Network has been the examination of the discourse(s) of education across the Europe under the title ‘Tower of Babel or Conversational Community?’. Even, or especially, under the conditions of the sort of research group practices made possible by developments in ICT and web-based communications one of the requirements of a research group of any sort is some capacity to communicate and share meaning, some common language – ‘paying for the privilege of sanity with common coin, with meanings we’ve agreed upon’ (Atwood 2001). Perhaps beyond this we need what Hunt has referred to as ‘the discipline of a discipline … the rules of conduct governing an argument within a discipline… the rules of conduct (which) make a community of arguers possible.’ (Hunt 1991: 104 and see also Popkewitz: 1984). Perhaps another route for philosophers to take into the topic of the research group is to examine more closely the discipline, the rules of conduct or the discourse requirements which make such a group possible. referred to different books and only rarely joined in common debate’. This allegiance to particular genres and fora is pretty close to John Swales’ classic definition of discourse communities: Discourse communities are sociorhetorical networks that form in order to work towards sets of common goals. One of the characteristics that established members of these discourse communities possess is familiarity with the particular genres that are used in the communicative furtherance of those sets of goals. In consequence, genres are the properties of discourse communities; that is to say, genres belong to discourse communities, not to individuals, other kinds of grouping or to wider speech communities (Swales 1990: 9). A key question, for this present forum, then, would be whether it can establish goals that are sufficiently inclusive to allow for the opening up of a new discursive ‘space’ for productive engagements of research/philosophy/education. I am not sure how general those shared goals would need to be in order to allow everyone to be counted in. Personally, I would be comfortable within a discourse community whose philosophical (and indeed educational) intentions inclined towards scepticism, critique, provocation and resistance to simplification. I would be less sure about joining a community whose philosophical inclinations were to arbritrate, discriminate, evaluate, settle educational questions, or offer ‘masterful’ interpretations. (Maggie MacLure) 8 Contact d.bridges@uea.ac.uk if you would like to be added to this list. 10 Summary and Conclusion It might be helpful in conclusion just to pull out some of the issues raised in this chapter which might provide a focus for discussion. These have included: (i) the question of whether attempts to structure research under ‘research groups’ represents an imposition of a model of research production drawn from one part of the academy onto other parts to which it is less suited? What are the consequences for our research of being required to fit into this model? (ii) questions to do with the social order of research groups and the sort of principles which most helpfully (logically or empirically) support research endeavour; (iii) questions to do with the mutual ethical obligations which do or ought to underpin relations within a research group. Are these adequately expressed, as I was beginning to argue, in terms of obligations of critique and of support? (iv) questions to do with the role of ‘the philosopher’ in an interdisciplinary or multi-disciplinary research group. (v) questions to do with the problematisation of that identity: of ‘nonphilosophers’ who seem to be doing philosophical work and of ‘philosophers’ (most and perhaps all of them) whose intellectual role and resources cannot be reduced to the philosophical; (vi) questions to do with what anyone qua philosopher can make of empirical data; (vii) questions to do with how philosophers and those in the educational research community who would not define themselves in these terms can engage more effectively together; (viii) questions to do with the conditions which ‘make a community of arguers possible’ within a research group and, more problematically within looser educational research groupings/networks which cross all sorts of linguistic and cultural as well as epistemic frontiers. This summary of issues arising from a single contribution to the Leuven symposium suggests that, as the organisers presumably suspected, the topic of the research group might be a fertile one for continuing exploration – by philosophers and others. References Atwood, M. (2001) The blind assassin, London, Virago. Bridges D (1979) Education, democracy and discussion, Slough, NFER/Nelson. Re-printed (1988) University Press of America Bridges, D. (1988) ‘A philosophical analysis of discussion’ in ed J. Dillon, Questioning and discussion: a multi-disciplinary study, Norwood, N.J. Ablex. Bridges, D. (1997) ‘Philosophy and educational research: a reconsideration of epistemological boundaries’, Cambridge Journal of Education, vol 27 no 2 pp 177-190. Bridges, D., (1998) ‘On conceptual analysis and educational research: a response to John Wilson’, Cambridge Journal of Education 28:2 pp 239-241. 11 Bridges, D., (1999) Writing a research paper: reflections on a reflective log, Educational Action Research, 7:2 pp 221-234. Bridges (2003) Fiction written under oath? Essays in philosophy and educational research, Amsterdam, Kluwer. Burbules, N.C. & Callister, T.A. (1999) Universities in transition: the challenges of new technologies. Paper presented to the Cambridge Philosophy of Education Conference, 18 September 1999. Dillon,J., (1988) Questioning and discussion: a multi-disciplinary study, Norwood, N.J. Ablex. Elliott, J., (1998) The curriculum experiment: meeting the challenge of social change, Buckingham, Open University Press. Elliott, J., Bridges, D., Ebbutt, D., Gibson, R. and Nias, J., (1981) School accountability: the SSRC Accountability Project, London, Grant MacIntyre. Farrar, S., (2002) Co-authors should play greater part in ensuring validity of research, Times Higher Education Supplement: News Analysis, October 4th, p7. Hunt, L. (1991) History as gesture; or the scandal of History’ in eds. J. Arac and B. Johnston, Consequences of theory, Baltimore, John Hopkins University Press. Knitter, W. (1988) ‘Review of disciplinary perspectives’ in ed. J. Dillon, Questioning and discussion: a multi-disciplinary study, Norwood, N.J. Ablex. MacMillan, C.J.B. (1988) ‘An erotetic analysis of teaching’ in ed J.Dillon, Questioning and discussion: a multi-disciplinary study, Norwood, N.J. Ablex. Popkewitz, T.S. (1984) Paradigm and ideology in educational research: the social functions of the intellectual, London and New York, Falmer. Simons, H. ed. (1980) The science of the singular, Norwich CARE Occasional Publications Swales, J.M., (1990) Genre analysis: English in academic and research settings, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. Wilson, J., (1994) Philosophy and educational research: first steps, paper presented to British Educational Research Association Annual Conference, Oxford. Wilson, J., (1998) ‘Philosophy and educational research: a reply to David Bridges et al.’, Cambridge Journal of Education vol 28, pp 129-33. Wilson, J., Williams, N., & Sugarman, B., (1967) Introduction to moral education, Harmondsworth, Penguin Books. 12 13