Organize for GenyWise

advertisement

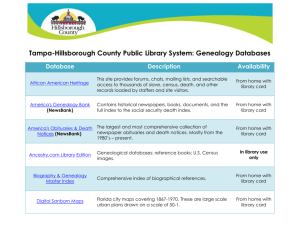

ORGANIZATION for GENEALOGISTS OBJECTIVE: In this discussion and demonstration we will learn how to mentally and manually organize the process of your research. We will learn to use key forms for an efficient pedigree pursuit. SUPPORTING IDEAS: 1. It is important to understand research principles first. [see section II and a separate Forum] 2. Successful researchers know how to use and locate the appropriate sources. In this kind of research you will find a great many unrelated facts and clues. An item here and an item there may seem to have no connection, and yet a third item may link the three together. Such a happy combination obviously would be impossible if, through bad organization, the first two were not accessible when the third was found two months or even three years later. 3. It is essential to organize in such a way that you and anyone else can repeat a search, locate the same source, and know which source to search next for any family and locality. This aspect of historical research seems to have suffered great neglect, especially by genealogists, and especially since more and more people choose to live or die at the mercy of a computer. Yet genealogical work requires just as much care and intelligence as any other kind of research subject. And it is not dependent on a machine to be successful. I. INTRODUCTION A. welcome to the class B. pre-assessment quiz C. class objectives and handouts D. case study example [demonstrate use of your own successful system] PRE-ASSESSMENT Which category of disorganized genealogists do you belong to: 1) those who meet such rapid success that they do not take time to record all they are finding 2) those so lost on a dead-end ancestor that their search becomes increasingly desperate, unsystematic, and unrecorded 3) those who follow the amoeboid approach, wandering around and bumping into books and computers and microfilms 4) other: II. Understand research principles and pitfalls $ pedigree analysis + evaluation of sources What kind of record is it? Is the record an original or a copy? What kind of evidence does it offer? Who made the record? When and where was the record made? Does the record make sense? What other evidence do you have? On a family tree chart you can use ink and pencil together to remind you of the value of your evidence. Various clues written in pencil indicate they are not proven very well. They need further research and documentation. Items marked in pen, on the other hand, mean you have verified facts and have documents filed away to back up the facts. $ paleography [see my Group class on Handwriting], geography, history $ notekeeping and correspondence III. Use historical traces: original and secondary $ representational - material - immaterial - written $ types of sources: vital, church, census, immigration, military, probate, etc. Locate the sources: the jurisdictional approach $ home and family / town and city / county / state / national / international & Internet IV. Organize your genealogical pursuit -be creative; use the system that works for you; don't confuse the end with the means -keep it simple... something you can separate and carry -flexible... like in three-ring binders -workable... so you can find something fast -affordable... so it can grow There are various patented devices for holding notes, or for preserving family records. Square charts, radial or fan-shaped charts, family trees carved in wood. To start, I suggest you try a 3-ring notebook for each of your four grandparent lines. You'll be pleased at what can fit into it, and how easily items can be re-arranged in it! $ start each research project with a plan - publish or perish In starting out on a genealogical pursuit you must be aware of one important fact. It is this: that before you finish your search you will possess an addiction and a huge heap of notes, manuscripts, maps, photocopies, and many strange little yellow or pink stick-ums that came from goodness knows where. It is vitally important, therefore, to start out with a definite plan for arranging and filing this material. $ use a device to keep and retrieve every pertinent item $ use standardized formats for your notebook (or computer) - uniform sizes of paper - artifacts and photos should be kept archivally acid-free a. Pedigree chart** / family tree / ancestral lineage chart b. Family group records - add an individual source history for complicated lines (a PC helps here) c. Maps, chronologies, research aids d. Resource check list / search control form / to-do list e. Research log*** / calendar of search; correspondence log - this is the table of contents! - add a research report or summary to share with relatives f. Document extract form / single source form; photocopies - photocopies are better than transcripts; or extract portions, or abstracts - don't carry original historical documents around Other useful weapons: pencil case tab dividers lined paper pocket recorder/notepad pencil/eraser 3-ring pockets blank forms OTHER TIPS FOR THE BATTLE F Make a note of every source you search - especially if you seem to find nothing pertinent. You may spend a day or two going through books and microfilms without finding a single reference to your family, but your activity was not wasted. Such activity is call "negative results". That is, you did not seem to find what you were looking for, yet if you did a careful search you know that what you are looking for is not in the fifty or sixty sources you consulted in those two days. F Note complete citations to build a "works consulted" file which instantly tells you what you have already done. = author, title, publisher; custodian; call number, volume, page number, document number = what most research logs are missing is a column for “surnames searched” F The cure for most genealogical problems is a combination of being organized and limiting the search to a specific time period and locality. F Always complete a preliminary survey of secondary sources to see what has been done already. If on the Internet, track the websites you visit very carefully. A common obstacle in genealogy is the "first step" of getting started. For a good researcher that means completing a preliminary survey of secondary sources to see what has been done already. The preliminary survey, for which there are many reference aids and articles, must be conducted for each name on the pedigree as it is discovered. F Always selecting an objective for research in original records This means you will reach your goal. The selection of an objective is done by answering these questions: * What do I already know? * What does this suggest? F A genealogist should consider himself a one-person jury in a Court of Genealogy, weighing evidence, applying logic and making decisions. The reference books by Elizabeth S. Mills are all you need when it comes to evidence. Genealogy is event-oriented. The evidence you find which concerns your people is located in the records made of events in those people's lives. Events are generally recorded in the localities where they occurred. At your own discretion you may add to the flood of inaccurate pedigrees, or you may choose to produce an accurate genealogy by applying the rules of evidence and common sense. The genealogical information found in the library or website may be correct or false. Each researcher must decide to accept the information totally or partially or not at all. Then you should continue your research to discover facts which justify your decision. In genealogy, since personal knowledge is usually lacking, the rule is that ancestry may be established by a preponderance of the evidence. This does not mean weighing ten family books stating the same acts against one book which differ. It means quality, not quantity, is our standard. F The problems of genealogical research include: - Genealogy is more of an art than a science. - The interpretation of genealogical data is very subjective. - Conclusive proof is NOT possible in genealogical research. - An identity problem exists for each person in each locality. - The value of references in compiled genealogies is doubtful. - Fraud and negligence are common (especially when it comes to heraldry and royalty). - Most sources were NOT created for genealogical purposes. - Genealogical information is hearsay evidence. POST-ASSESSMENT Are you a self-made genealogist? Are you a law unto yourself, operating with your own set of rules? Are you muddying the past by copying and passing on genealogical data from unreliable sources? Do you attempt to verify the results of all researchers? In 2009 or 2019 will another family member be able to tell what you have searched?