Tennis Facility Planning Guide - Sport and Recreation Victoria

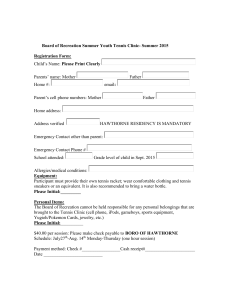

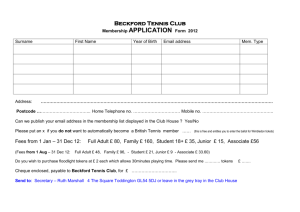

advertisement