Figure 3: A Game Table of the Study Game

advertisement

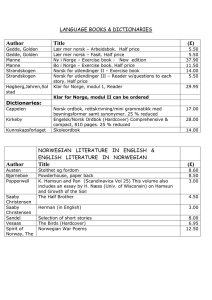

Del 1 (In english) WHAT IS STRATEGIC BEHAVIOUR? In the basic competitive behaviour model and in a monopoly, individuals and firms do not need to behave strategically. The reason for this is that the basic competitive model creates the condition of perfect competition, where each firm and individual is a price taker that cannot influence the market price, and with a monopoly, there simply is no competition. When markets are, however, structured in such a way that there exists imperfect competition, strategic behaviour becomes important. With imperfect competition several firms are each aware that their sales depend on the price they charge and possibly other actions they take, such as advertising. There are two special cases where the imperfect competition market structure is relevant to us: oligopoly (when there are sufficiently few firms that each must be concerned with how its rivals will respond to any action it undertakes) and monopolistic competition (when there are sufficiently many firms that each believe that its rivals will not change the price they charge should it lower its own price, and that profits may be driven down to zero). Strategic behaviour is basically decisions that take into account the possible reactions of others. For understanding strategic behaviour we use game theory. Economists have found that many examples of strategic behaviour can be understood by relying on the core concepts of incentives and information. Behaving strategically means that each player must try to determine what the other player is likely to do. Rollback is crucial for strategic behaviour- thinking strategically means looking into the future to predict how others will behave and then using that information to make decisions. Game theory provides a framework for studying strategic behaviour. The objective is to predict what strategy each player will choose, and to predict the outcome of the game- its equilibrium. John Nash developed the most fundamental idea for predicting the actions of players in a strategic game. This theory is called the Nash equilibrium, and in it each player in a game is following a strategy that is best, given the strategies followed by the other players. A game may have a unique Nash equilibrium or it may have several equilibrium. That depends on the strategy. A strategy is a plan of action and to predict the outcome of a game one needs to ascertain whether the strategy is a dominant strategy or not. A dominant strategy is one that works best, no matter what the other player does. It is easy to predict the outcome of a game, the Nash equilibrium, if both players have a dominant strategy. A game that illustrates this ease when a situation exists where each player has a dominant strategy is the ‘Prisoner’s Dilemma’. Although we have heard it all before, it is worth recapping: Two Prisoner’s 1 and 2, are alleged by police to be conspirators in a crime. After being taken into custody, they are separated. A police officer tells each that if the prisoner confesses and his co-conspirator does not, then the prisoner will not get any jail time. If both co-conspirators confess then they will both get five years imprisonment. If they both do not confess they will both get one year in jail. But if the prisoner does not confess and his co-conspirator does confess, then he will receive 15 years in jail. It is easiest to understand using a game table (Figure 1 below) Figure 1 A Game Table Based on self-interest, each individual prisoner believes that confession is best, whether his partner confesses or not. By following their self-interest and confessing, they both end up worse off than if neither had confessed. They are both following their dominant strategy and it is a strategy that works best no matter what the other prisoner should decide to do It is also possible, however to have games with either only one player with a dominant strategy or neither player having a dominant strategy at all. To explain these circumstances economists have devised a game called the Bertrand price-cutting game. Two firms, Company A and Company B, produce identical products that compete with one another. Company A has a dominant strategy- reduce prices. It makes more money with this strategy, regardless of what Company B does because it has an incentive to reduce its price below that of Company B as long as the price is above marginal cost. If each is charging the same price, then they split the market. If the price is above marginal cost, they both make a profit. But what if one charges a (slightly) lower price? Its profit per unit falls (a little, since the price cut was small), but because it gets the whole market its profits go up. (For a small enough price reduction, profit should almost double.) Therefore it has a clear incentive to reduce price. Even though Company B does not have a dominant strategy, we can predict what it will do. Company B will have to reduce its prices because company A has that as its dominant strategy. The optimal strategy for each firm, then, is to reduce price below the other, unless price equals marginal cost. Since each firm is trying to undercut the other, we end up with price equal to marginal cost. In game theory terms, this is a Nash equilibrium. Company A Company B Reduce Do not reduce 2.5 1 Reduce 5 6 3 3.5 Do not reduce 1 2 Figure 2: A Game Table of Bertrand’s Price-Cutting Game Some circumstances have 2 players both without dominant strategies. They give rise to outcomes with more than one Nash equilibrium. The study game outlined in SAW illustrates this point. Two friends decide to study together. They are both enrolled in the same class for economics and public administration and both agree that their performances on upcoming exams will improve if they study together. However Student A would prefer to spend time studying economics, whilst Student B would prefer to study public administration. The game table in figure 3 expresses payoffs in the average grade for the two courses. Neither student has a dominant strategy, one that is best regardless of what the other does. But there are 2 Nash equilibria in this game- to either both study economics or public administration. So whilst the concept of a Nash equilibrium may not lead us to predict a unique equilibrium in a game, it can help us to eliminate some outcomes. Student A Student B Study public admin Study public admin Study economics B A C C Study economics A C C B Figure 3: A Game Table of the Study Game In the three games described above, each party makes only one decision. The games are played only once. But it sometimes occurs that the games played are played many times over. They are called repeated games and the strategies employed become more complex. To illustrate this point SAW comes up with the example of two firms in a duopoly. Each duopolist announces that it will refrain from cutting prices as long as its rival does. But if the rival cheats on the collusive agreement, then the first duopolist might respond by increasing production and lowering prices. With repeated games it is even more important to look to the end result and work backward to identify the best current choice. Making decisions this way is called backward induction or rollback. Back to the example of the duoplolists. Collusion in a repeated game setting can function because in strategic game’s that do not have a finite end there are a number of strategies that may allow players to cooperate to achieve the best outcome. These strategies include: developing a good reputation with customers and other firms, the existence of a strategy called ‘tit for tat’ where the threat of increased production will achieve cooperation in competition, as well as institutions such as The World Trade Organisation that serves to enforce agreements between nations. In the prisoner’s dilemma, each player had to make a decision without knowing what the other player was going to decide. Many instances lead to a sequential decision making process, one player decides first and the second player responds to the choice made by that player. In this type of game, the sequential game, the player who moves first must consider how the next player will respond. We use a tree diagram to simplify the complex scenario of sequential games. (see presentation). Threats and time consistencies are two occurrences that are common components of strategic behaviour. Threats we have already delved into, and time inconsistencies simply is the case when the strategic choices have been made but carrying out the initial strategy might no longer be the best option, The example found in SAW of the college student whose parents want her to find a summer job illustrates this strategy well. Del 2: Fangens dilemma Oppgave 2a: (Fra Stiglitz & Walsh side 399) Marlboro og Benson & Hedges Denne oppgaven handler om mulige konsekvenser av å reklamere eller ikke å bruke penger på reklame for to konkurrerende firmaer med produkter som retter seg mot det samme markedet. Marlboro og Benson & Hedges er blant verdens største produsenter av tobakksvarer. Hvis bare det ene firmaet investerer i markedsføring, vil det ene firmaet i teorien få en større del av markedet. Hvis begge bruker penger på dette, vil markedsandelene i teorien holde seg på samme nivå. Dette vil antakelig også hende hvis ingen bruker noe på reklame. Tobakksreklame er i de fleste land forbudt eller er forbundet med strenge restriksjoner og hvis man går ut fra at dette er en markedssituasjon hvor reklame for tobakk er lov, men underlagt et strengt regelverk. For å få et bilde av situasjonen er fangens dilemma en anvendbar måte for å redusere abstraheringen av en markedssituasjon med få, jevnstore aktører (for eksempel oligopol). Egentlig dreier oppgaven seg om strategisk adferd, hvor to konkurrerende firmaer må forutse de andres planer for å kunne møte konkurrenten med samme tiltak for å beholde sin posisjon i et marked. Marlboro Benson & Ikke reklame Hedges Reklame Ikke reklame B&H Marlboro 100 100 mill mill profitt profitt B&H Marlboro 150 50 mill mill profitt profitt Reklame B&H Marlboro 50 mill 150 mill profitt profitt B&H Marlboro 70 mill 70 mill profitt profitt Hvis begge firmaene bruker penger på reklame, vil profitten synke litt, men begge beholder samme markedsandeler i prosent. Oppgaven tar også opp hvorfor tobakksprodusentene klager på statlige restriksjoner på kampanjer for produktet tobakk. På en måte vil jo faktisk begge tjene mest på at ingen reklamerer. En uheldig konsekvens fra en del sitt synspunkt, kan være at det å ha restriksjoner på produkter som er lovlige, faktisk i prinsippet er å begrense ytringsfriheten. Det kan også være at det kan virke som en stat som vil ha restriksjoner på enkelte produkter. Det kan også virke som om ideologer hos myndighetene har et ønske om å kontrollere private bedrifter eller påvirke eventuelt begrense ett individs rett til å utrykke seg og å foreta selvstendige valg. Oppgave 2b Ta for deg to rivaler, produsenter av film til kamera. Forbrukerne ønsker en film som reproduserer fargekvaliteten og som ikke er “kornete”. Både Kodak og Fuji har filmer som er sammenlignbare i kvalitet. Men om en av produsentene gjør forskning og forbedrer sitt produkt, vil denne produsenten stjele kunder fra produsent nr. 2. Om dem begge gjennomfører forskning, og forbedrer kvaliteten på sitt produkt, vil de fortsette å “dele” markedet som tidligere. Spørsmål 1: Hvorfor vil begge tjene på å gjennomføre forskning av sitt produkt, selvom deres profitt blir lavere? Begge produsenter må tenke; “for hvert valg jeg eventuelt vil foreta, hva er det beste valget rivalen min vil foreta?” Om vi tar utgangspunkt i Kodak. Hvis Kodak velger å forske på sitt produkt, hva er den beste strategien til Fuji? Og hvis Kodak velger å ikke forske på sitt produkt, hva er da den beste strategien til Fuji? I begge situasjoner ser vi at det beste for Fuji er å forske på sitt produkt. Hvis det beste for Fuji er å forske, hva er da den beste strategien for Kodak? Vi foretar den samme metoden som over: Hvis Fuji velger å forske på sitt produkt, hva er den beste strategien til Kodak? Og hvis Fuji velger å ikke drive forskning på sitt produkt, hva er da den beste strategien til Kodak? Vi ser at både Fuji og Kodak vil tjene på å forske på sin film, uansett hva rivalen velger å gjøre. Spørsmål 2: Vil samfunnet tjene på at både Kodak og Fuji driver forskning på sitt produkt, selv om profitten er lavere? Når begge velger å drive forskning, og videreutvikle sammenliknbare produkter, vil begge produsenter fortsette å “dele” markedet. Det vil da oppstå ny konkurranse og konsumentene vil kunne kjøpe et enda bedre produkt. Del 3. Angi likevekten i et marked med monopolistisk konkurranse. A: optimal profitt får en bedrift ved å produsere den mengden der grenseinntekt er lik grensekostnad og selge til den prisen konsumentene er villig til å gi. Prisen ligger over kostnad og de får profitt. Profitt lokker til seg flere konkurrenter. B: med flere konkurrenter som deler på etterspørselen blir etterspørselen til bedriften i A mindre. Der prisen til etterspurt mengde er lik kostnadene går de verken med overskudd eller underskudd. Som vi ser, ligger kostnadene ellers over prisnivået. Likevekten vil derfor være der grenseinntekt er lik grensekostnad.