TWENTIETH CENTURY IRISH FICTION

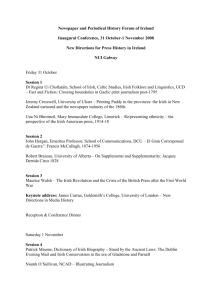

advertisement