Report of the Psychiatric Drug Safety Expert Advisory Panel

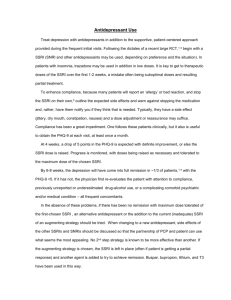

advertisement