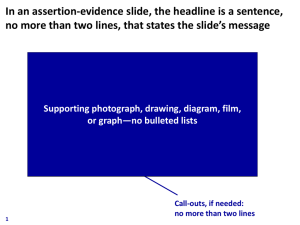

Relativism, Assertion, and Belief

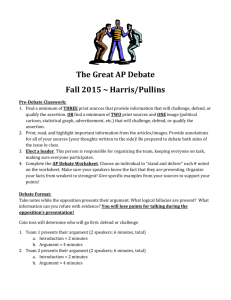

advertisement