Trademark Registration and Protection

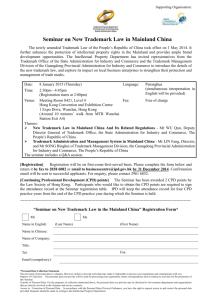

advertisement