Quite a challenge: Article 263(4) TFEU and the case of

advertisement

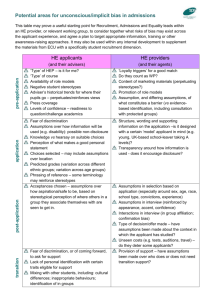

Quite a challenge: Article 263(4) TFEU and the case of the mystery measures Richard Lang1 1. Introduction When Winckler talks of Article 263(4) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union requiring further precision2, he is surely not wrong. A child of many parents3, the new article was almost not born at all, and was only saved – perhaps – by the deft intervention of Prime Ministerial midwives at the Brussels summit of mid-2007. It was a sickly baby that emerged – an emaciated skeleton much in need of the post-natal care of the Court of Justice to put some urgently-needed flesh on its bones. For those keeping the bedside vigil, anxiously hoping that all will be well, the present paper is intended as an even-handed prognosis, not a death-knell. The new article can survive; it may even go on to live a life surpassing all expectation. But, like any professional advice, this prognosis must also consider the possible dangers lying in its path. 2. The situation before Lisbon 2.1. The old and new wording of the provision governing judicial review for private applicants The Treaty of Rome has always contained a provision on judicial review, and this provision has always drawn a distinction between different types of potential applicant. In its original, pre-Maastricht version, Article 173 EEC (as it then was) recognized two categories of applicant: Member States, the Council and the Commission on the one hand, and natural or legal persons on the other. The first category (the so-called “privileged” applicants) was dealt with in Article 173(1) EEC and was given unrestricted locus standi to challenge Community acts, while the second category (the “non-privileged” applicants, with whom this paper is concerned) was dealt with in Article 173(2) EEC and was given very restricted locus standi. The Maastricht amendments allowed for an intermediate “semi-privileged” category, consisting originally only of the European Parliament and the European Central Bank, the members of which could challenge the legality of EC legislation but only in so far as it was protecting their own prerogatives4. As a result of this, and the fact that the first paragraph was split into two, the rules on non-privileged applicants were now to be found in the fourth paragraph: Article 173(4) EC. They have remained in the fourth paragraph ever since, although the article number has changed twice – once at Amsterdam, so that the relevant paragraph became Article 230(4) EC, and again thanks to the Treaty of Lisbon (or “Reform 1 BA(Hons), LL.M, Ph.D. Senior Lecturer, School of Law, The University of Bedfordshire. Of Counsel, Kemmler Rapp Böhlke & Crosby, Brussels. The author wishes to thank Vanessa Gamet for her help in sourcing one of the articles mentioned herein, and Thomas Unger for his linguistic skills. All mistakes are author’s own. 2 “Si cette ourverture est bienvenue, il reste encore à en préciser les contours”: A Winckler, “Le traité de Lisbonne et l’organisation de la Cour de Justice de l’Union européenne” L’Observateur de Bruxelles 2010, n. 80, April, 21, 24. 3 The Convention on the Future of Europe, which met in Brussels between February 2002 and July 2003, and which produced the draft Treaty establishing a Constitution for Europe, consisted of some 105 full members, not including alternates and observers. 4 This was effectively a codification of the Court’s judgment in the “Chernobyl” case: Case C-70/88 European Parliament v Council of the European Communities [1990] ECR I-2041. There has been a fair amount of reorganization affecting this intermediate category over the years. The European Parliament, for example, was eventually upgraded to the first category, while the Court of Auditors and Committee of the Regions have, at different stages, joined the ECB in the semi-privileged group. 1 Treaty”), as a result of which the pertinent subsection is currently to be found at Article 263(4) TFEU. Despite all of this relocation and renumbering, however, the wording of the subsection concerning non-privileged applicants had never itself changed – until Lisbon. The original wording was as follows: Any natural or legal person may, under the same conditions, institute proceedings against a decision addressed to that person or against a decision which, although in the form of a regulation or a decision addressed to another person, is of direct and individual concern to the former. According to this wording, a non-privileged applicant could challenge: (1a) A decision addressed to him; (1b) A decision addressed to another person, which was of direct and individual concern to him; or (1c) A decision in the form of a regulation, which was of direct and individual concern to him. After Lisbon, however, the wording changed to the following: Any natural or legal person may, under the conditions laid down in the first and second paragraphs, institute proceedings against an act addressed to that person or which is of direct and individual concern to them, and against a regulatory act which is of direct concern to them and does not entail implementing measures. According to this, new wording, a non-privileged applicant would henceforth be able to challenge: (2a) An act addressed to him; (2b) An act addressed to another person, which was of direct and individual concern to him; or (2c) A regulatory act which was of direct concern to him and did not entail implementing measures. To describe these classes as classes of challengeable act is not quite right. Each class has an objective and a subjective element; it is not only the type of act which is relevant, but the situation of the would-be challenger in relation to it. The challenger thus bestows challengeability on the act; it has no intrinsic challengeability (in the realm of non-privileged applicants, anyway) 5. 2.2. The early case-law Under the original wording, a large body of case-law was developed by the Court of Justice, and later the Court of First Instance, when it was granted the right to hear direct actions. This case-law cannot be done justice in a short paper, and those interested should consult 5 A philosopher might say it has no a priori challengeability. 2 more specialist works for details.6 The following points should be made, however, to facilitate understanding of the later argument. Private applicants challenging Decisions addressed to them of course faced little difficulty in gaining admittance to court, as their situation fell perfectly within class (1a) above. Where the Decision was addressed to someone else though (class (1b)), things became trickier, as the twin requirements of direct concern and individual concern now had to be fulfilled. Direct concern, which the Court interpreted as meaning that the measure left no (or at least little) discretion to the Member States at the implementation stage, posed few problems. An example of a case where direct concern was found is Freistaat Sachsen7, where it was held that Germany had no discretion in implementing the Commission’s decision on illegal State Aid, challenged by one of the affected regions. Meanwhile, one of the cases where the applicant failed to show direct concern was Municipality of Differdange8, where a Commission decision on capacity-reduction in the steel industry left such a margin of discretion to Luxembourg as to which factories to close and so on, that the challenger – a municipality affected by the closures – could not be held to be directly concerned by it. A case which went the other way to Municipality of Differdange was International Fruit9, where the Court was prepared to accept that, although the Member State in question – the Netherlands – had exercised discretion in issuing or refusing import licenses to fruit importers (of which the applicant was one), this issue or refusal was “bound up with”10 the Commission’s original Decision on the matter, leaving the chain of causation unbroken as between the Commission and the company. Individual concern, on the other hand, proved to be something of a can of worms. In the leading case, Plaumann, an importer of non-EU clementines attempted to challenge a Commission Decision, addressed to Germany, which maintained certain duties on precisely this category of clementine.11 The Court held that an applicant would only succeed in showing that they were individually concerned by such a Decision “if that decision affects them by reason of certain attributes which are peculiar to them or by reason of circumstances in which they are differentiated from all other persons and by virtue of these factors distinguishes them individually just as in the case of the person addressed.”12 Mr Plaumann was unable to show such distinguishing attributes; the Court was clearly of the opinion that anyone could import clementines. The matter is sometimes described in terms of “open” and “closed” categories of applicants. Mr Plaumann was refused admission to the Court as he was a member of an open category (at least on the Court’s interpretation of the clementine business). The Court will however grant standing to those who can show that 6 In particular, Anthony Arnull’s two articles in the Common Market Law Review are recommended: A Arnull, “Private applicants and the action for annulment under Article 173 of the EC Treaty” 32 CMLRev (1995) 7, and A Arnull, “Private applicants and the action for annulment since Codorníu” 38 CMLRev (2001) 7. 7 Case T-132/96 Freistaat Sachsen and others v Commission [1999] ECR II-3663. 8 Case 222/83 Municipality of Differdange and Others v Commission [1984] ECR 2889. 9 Case 41-44/70 NV International Fruit Company and others v Commission [1971] ECR 411. 10 Ibid., Para. 27. 11 Case 25/62 Plaumann & Co. v Commission [1963] ECR: English special edition, 95. 12 Ibid., Part I of the Grounds. 3 the category of applicant into which they fall is closed, that is, incapable of taking any new members; an example is Toepfer13, where a certain decision of the German government to delay the granting of a licence to import grain only affected those who had applied for the licence on 1st October 1963. As this was a completed past event, the category of grainimporters applying on that day (which of course included the applicant) was closed to any new members. Mr Toepfer was thus individually concerned. Over the following decades, the Court was conspicuous for the harsh way in which it carried out the already harsh Plaumann test. Various local residents, fishermen and farmers, for example, who wished to challenge a Commission Decision concerning the construction of power stations addressed to Spain, were denied standing on the grounds of being unable to show any attributes which distinguished them individually in the way the Court had described in Plaumann14. This harshness can be seen not only in relation to private applicants falling within class (1b), but also those falling within class (1c). As Eliantonio and Kas put it15, even greater hurdles face the challenger of a Regulation (as opposed to a Decision addressed to someone else), as these applicants also have to convince the Court that the contested Regulation is a “decision in the form of a regulation”, that is, a Decision in disguise. The test for determining whether a Regulation is truly a Decision is whether or not it is truly legislative in character, that is, whether it applies to objectively determined situations and has legal effects on classes of persons defined in a general and abstract manner; this test can be found set out, among many other judgments, in the Calpak case.16 The case-law shows, however, that a provision in a Regulation which is otherwise legislative in character may be regarded as a Decision if it is severable from the “legislative whole”.17 Another solution was found in International Fruit, considered above in relation to direct concern; here, the Court held that the contested Regulation was not a provision of general application, but a “conglomeration of individual decisions”. On the other hand, the legislative character of a measure is not affected by the fact that it may be possible more or less precisely to determine the number and even the identity of the persons to whom it applies so long as it is applied by virtue of an objective legal or factual situation defined by the measure. Thus a Regulation relating to only one product manufactured by a small number of producers is no less a Regulation for that reason.18 Nor does the fact that it has an unequal effect on the person affected by it prevent it being a “true” Regulation.19 The rule that a “true” Regulation could never be challenged by a private applicant was rewritten, however, with the case of Cordorníu20. Here, a Spanish producer of sparkling wines attempted to challenge a Council Regulation reserving the term “crémant” for sparkling wines of a particular quality coming from France or Luxembourg. Importantly, 13 Case 106-107/63 Alfred Toepfer and Getreide-Import Gesellschaft v Commission [1965] ECR: English special edition 405. 14 Case T-585/93 Stichting Greenpeace Council (Greenpeace International) and others v Commission [1995] ECR II-2205. 15 M Eliantonio and B Kas, Private Parties and the Annulment Procedure: Can the Gap in the European System of Judicial Protection Be Closed?” [Sept 2010] 3 Journal of Politics and Law 2, 121, 122. 16 Cases 789 and 790/79 Calpak SpA and Società Emiliana Lavorazione Frutta SpA v Commission [1980] ECR 1949. 17 Cases 16-17, 19-22/62 Confédération nationale des producteurs de fruits et légumes and others v Council [1962] ECR: English special edition 471. 18 Joined Cases 97, 193 & 215/86 Asteris AE and others and Hellenic Republic v Commission [1988] ECR 2181. 19 Case 101/76 Koninklijke Scholten Honig NV v Council and Commission [1977] ECR 797. 20 Case 309/89 Codorníu SA v Council [1994] ECR I-1853. 4 Cordorníu held a trademark which included the word “crémant”. The Council argued that the measure was a Regulation within the Calpak test, and the fact that it was possible to identify the number or identity of those affected by it made no difference. However, the Court held: “Although it is true that according to the criteria in the second paragraph of Article 173 of the Treaty [as it then was] the contested provision is, by nature and by virtue of its sphere of application, of a legislative nature in that it applies to the traders concerned in general, that does not prevent it from being of individual concern to some of them.”21 Codorníu’s having registered the trademark was a distinctive enough attribute to allow the company to show individual concern under Plaumann; their application was therefore admissible. In the days of Calpak, then, “general” and “individual” were simple opposites: a Regulation was either the one or the other. What Codorniu did was to explode that myth by demonstrating that a Regulation could in fact have both characteristics at once, that is, it could be general from an objective standpoint, but individual from a subjective one. It follows that in order to reach a proper decision as to whether a certain Regulation is challengeable by a certain applicant, the bench must consider a small amount of the substance of the action (that is, not just the circumstances of the applicant, but, crucially, how the contested measure impacts upon them) even at the admissibility stage, as happens in English judicial review hearings.22 The problem is that the ECJ is inconsistent here, varying the scrutiny under which it is prepared to put the individual situation of the applicants from strict – Codorníu – to cursory at best, as will be seen from the discussion of UPA23 and Jégo-Quéré24 which follows. 2.3. UPA and Jégo-Quéré: A drama in six Acts During the Golden Age, Spanish plays tended to follow a strict three-Act structure, which could roughly be summarized by the expression, “order - order disturbed - order restored”. Subverting this, the UPA/ Jégo-Quéré drama starts with the stage in a state of disorder in Act 1, describes how an attempt was made to allay this disorder in Acts 2 and 3, before finally showing the reaffirmation of the original disorder in Acts 4, 5 and 6. The story has been told and commented upon many times before25, and is only recounted here by way of a brief introduction to the topic. 21 Ibid., Para. 19 (emphasis added). See AW Bradley and KD Ewing, Constitutional and Administrative Law (12th edn Longman, Essex 1997) 815-6, discussing the case of R v Inland Revenue Commissioners, ex p National Federation of Self-employed and Small Businesses [1982] AC 617: “What emerges from the various speeches is that the judges were reluctant to turn away the applicants without hearing something of their case”. 23 Case T-173/98 Unión de Pequeños Agricultores (UPA) v Council [1999] ECR II-3357 (“the CFI’s order”), on appeal Case C-50/00 P Unión de Pequeños Agricultores v Council of the European Union [2002] ECR I-6677 (“the Advocate General’s opinion”/“the ECJ’s judgment”). 24 Case T-177/01 Jégo-Quéré & Cie SA v Commission [2002] ECR II-2365 (“the CFI’s judgment”), on appeal Case C-263/02 P Commission of the European Communities v Jégo-Quéré & Cie SA [2004] ECR I-3425 (“the Advocate General’s opinion”/“the ECJ’s judgment”). 25 For two examples: F Ragolle, “Access to justice for private applicants in the Community legal order: recent (r)evolutions” [2003] ELRev 28(1), 90; CC Kombos, “The Recent Case Law on Locus Standi of Private Applicants under Article 230(4) EC: A Missed Opportunity or a Velvet Revolution?” European Integration online Papers (EIoP) Vol 9 (2005) No 17. 22 5 2.3.1. Act 1: The order of the Court of First Instance in UPA In 1966, the Council passed a Regulation organizing a common market for oils and fats; this was structured around a system of guaranteed prices and production aid. This Regulation obviously came to apply to Spain following the country’s accession to the EEC (as it then was) in the mid-Eighties. In 1998, however, the original Regulation was amended and the common market in oil was reformed. Among the reforms was a new emphasis on storage schemes in lieu of market intervention; aid to small producers was to be discontinued as from May 1998. Needless to say, many small producers of olive oil in Spain were affected by this. The new Regulation did not need to be implemented, that is, the withdrawal of aid would take place automatically, without any action needing to be taken at Member State level. The Unión de Pequeños Agricultores (“UPA”), a trade association which represented and acted in the interests of small agricultural businesses in Spain, and which had its own legal personality, attempted to challenge the 1998 Regulation before the Court of First Instance. UPA argued that the Regulation was not a legislative act, and that, even if it were, it could still show individual concern à la Codorniu.26 In support of the latter contention, the association mentioned the fact that the lack of aid was causing its members to go bankrupt, thus depleting its membership and weakening its own negotiating position, and the fact that the procedure followed in adopting the Regulation had been flawed. It also mentioned, importantly, that, since there was no Spanish implementing law which it could challenge domestically, a finding of inadmissibility by the European Court would leave it with no effective judicial protection. Lastly, UPA argued, it could not await the outcome of a preliminary reference under (what was then) Article 177 EC, even if a case could somehow be brought in a national court, as this would take too long. The Court of First Instance started by examining the nature of the Regulation. This, it held, amended the mechanisms for the common organization of the oils and fats market, and its field of application was defined in a general and abstract manner; it was, in other words, generally applicable. This finding was not vitiated by the fact that some economic operators in the sector were affected more than others. The operators in question were objectively determined, and the Regulation applied to all of them. The Regulation was thus legislative in nature, and could not be held to be a Decision in disguise. That said, UPA might still have standing under the Codorniu principle. However, the Court continued, its members could not satisfy the Plaumann test: clearly the Court’s view was that “anyone could produce olive oil”. Nor, in the CFI’s view, did UPA have any personal interest to speak of (as distinct from that of its members), and the argument based on the allegedly flawed procedure was a matter of substance, not admissibility. Finally, on the question of effective judicial protection, the Court held that the fact that no remedy existed for UPA at the national level was, to all intents and purposes, none of the European Court’s business. The duty of sincere 26 It should be noted that, according to long-standing jurisprudence of the Court of Justice, representative organizations could not normally have standing before the Court to challenge European legislation unless their individual members would also have had standing, acting separately. The case usually cited as authority for this, although not in fact the first to decide the point, is Case C-321/95 P Stichting Greenpeace Council (Greenpeace International) and Others v Commission of the European Communities [1998] ECR I-1651 (see Para. 14 of the Judgment). Exceptionally, the application of a representative organization might be held admissible despite its individual members’ lack of standing, if it could show “special circumstances”, such as the role it had played in the procedure which led to the adoption of the contested act: ibid., para. 15. In the case under discussion, UPA argued both positions – “individual interest” (see Para. 22 of the CFI’s order) and vicarious interest (ibid., Para. 23 et seq). 6 cooperation, under (what was then) Article 10 EC27, required Member States to provide such remedies, and whether or not a preliminary reference made by a national court under exArticle 177 would take too long was no justification for changing the system. UPA’s application was therefore inadmissible. 2.3.1.1. Acts 2 and 3: The Opinion of the Advocate General in UPA, and the Judgment of the Court of First Instance in Jégo-Quéré Although UPA relied on four pleas in its appeal before the Court of Justice, Advocate General Jacobs chose to concentrate on one only: that UPA’s fundamental right to effective judicial protection had been violated. In the event that recourse to the preliminary reference procedure was impossible owing to a lack of domestic measures to challenge, ran the argument, the Court should grant standing as a means of protecting this right. This led the Advocate General to begin his Opinion with a section questioning the assumption that the preliminary ruling procedure could in any event provide full and effective judicial protection “against general Community measures”. In his view, this assumption was “not correct”28 for, inter alia, the following – extremely abbreviated – reasons: A preliminary reference was not made as of right, but depended entirely on the discretion of the referring court; The questions were not drafted by the applicant; Use of the preliminary reference procedure led to increased delay; The referring court might not grant interim measures to protect the applicant in the meantime; The preliminary reference procedure excluded the author institution, at least in the early stages, and lacked a full exchange of pleadings; and There were no temporal restrictions on a preliminary reference, as there were on a direct action, meaning that an invalid act might remain in force longer than was necessary and leading to a reduction in legal certainty.29 Advocate General Jacobs next considered the approaches favoured by the two parties to the action. UPA’s favoured approach was, as mentioned above, that standing should automatically be granted, despite a failure to establish individual concern, where the applicant would otherwise be denied effective judicial protection. The Advocate General disagreed with this, inter alia on the grounds that it would involve the Court in a constant assessment of national laws, procedures and remedies, which, apart from going beyond the Court’s remit as set out in the Treaty, was something which it generally was not “well placed”30 to do. The Commission’s favoured approach was to leave it up to the Member States to provide a judicial avenue for the applicant at national level, such that he or she could have the benefit of a preliminary ruling in due course. The Advocate General disagreed with this approach as well, inter alia on the grounds that it would not address any of the arguments mentioned in the bullet points above, and might compel the Commission to monitor Member States’ provision or otherwise of said avenue under (what is now) Article 258 TFEU; in the event that an infringement action were brought before the Court, the same competence problems would arise as discussed in relation to UPA’s solution. 27 Now Article 4(3) TEU. Case C-50/00 P UPA, the Advocate General’s Opinion, Para. 35. 29 It is stressed that this is a highly condensed and incomplete summary of the reasons given by Advocate General Jacobs, which should not be substituted for a reading of the Opinion itself. 30 Case C-50/00 P UPA, the Advocate General’s Opinion, Para. 52. 28 7 Finally, then, the Advocate General unveiled his own preferred approach to the problem, which was to reinterpret the notion of individual concern, effectively decoupling it from the Plaumann test. The Advocate General’s new test took as its starting point the degree of adverse effect which the contested measure had or might have on the applicant. The more people affected by a measure, the Advocate General noted, the less likely they were to be able to distinguish themselves in the manner required by the Court in Plaumann, and yet the fact that the measure had such widespread impact was, in his opinion, a reason for making it susceptible to challenge, not a reason for immunizing it against challenge31. According to the new test, “a person is to be regarded as individually concerned by a Community measure where, by reason of his particular circumstances, the measure has, or is liable to have, a substantial adverse effect on his interests.”32 Among the advantages of the new test, Advocate General Jacobs mentioned the following: Individuals would never be without a remedy, thus addressing the effective judicial protection point; The challenge would take place in the best forum and pursuant to the best procedure, thus addressing the fifth concern in the earlier list; The fourth concern in the earlier list would also be addressed, as the Court of First Instance would be able to order effective, Europe-wide interim relief; Clarity, legal certainty and the quality of legal advice would increase; The number of preliminary references would decrease; and By affording private applicants all round Europe a single venue for potential challenges, the new test would promote the uniformity of EU law. Rejecting a number of predictable objections, Advocate General Jacobs concluded that the time was right for a new test for individual concern, and recommended that the Court of Justice find in favour of UPA. Just over a month after this Opinion was delivered, the Court of First Instance was due to give its judgment in another case: Jégo-Quéré. Here, the Commission, in a bid to save dwindling stocks of hake, had passed a Regulation which, amongst other things, set new minimum mesh sizes for fishing nets, and even prohibited some types of net in certain waters. Jégo-Quéré was a fishing company established in France. This company habitually fished for whiting off the coast of Ireland, which was one of the locations covered by the Regulation. However, fishing for whiting required a net with a mesh size smaller than that now authorized, which prompted Jégo-Quéré to attempt to challenge some provisions of the Regulation before the Court of First Instance. The parties’ arguments were predictable enough. The Commission argued that the application was inadmissible, as Jégo-Quéré could not show individual concern. The Regulation was a measure of general application, applying to objectively determined situations, and producing legal effects vis-à-vis classes of persons envisaged in a general and abstract manner; it was, in short, a legislative measure, not an administrative one. For its part, Jégo-Quéré argued that it could distinguish itself as the largest fishing company 31 “The fact that a measure adversely affects a large number of individuals, causing wide-spread rather than limited harm, provides however to my mind a positive reason for accepting a direct challenge by one or more of those individuals” (Ibid., Para. 59). 32 Ibid., Para. 60. 8 operating off the Irish coast, and the only one fishing for whiting (in large vessels, anyway). In the company’s view, the Regulation was not general, but a “conglomeration of individual decisions” within the meaning of such cases as International Fruit Company, discussed above. Finally, Jégo-Quéré asserted that, as the Regulation required no implementing measures on the part of France, there was no act for it to challenge at local level; a finding of inadmissibility would thus leave the company without access to a court, in breach of its rights under Article 6 of the European Convention on Human Rights. What was perhaps less predictable was the Court of First Instance’s ruling. The Court began by noting that the contested provisions were “addressed in abstract terms to undefined classes of persons”33 and were therefore of general application. In considering whether Jégo-Quéré could nevertheless challenge them under the principle laid down in Codorniu, the Court held that, while the company could show direct concern, it could not pass the Plaumann test for individual concern; in the CFI’s view, fishing for whiting was something anyone could do, and the company were unable to distinguish themselves to the requisite degree. Nor did Jégo-Quéré’s involvement in the procedure leading up to the adoption of the Regulation make any difference, in the absence of specific procedural guarantees. However, the CFI did observe that the company risked being denied a legal remedy altogether if standing were not accorded before the European Court. Taking up the gauntlet thrown down by Advocate General Jacobs, it therefore decided that the time was ripe for a new test for individual concern, which it phrased as follows: “[I]n order to ensure effective judicial protection for individuals, a natural or legal person is to be regarded as individually concerned by a Community measure of general application that concerns him directly if the measure in question affects his legal position, in a manner which is both definite and immediate, by restricting his rights or by imposing obligations on him. The number and position of other persons who are likewise affected by the measure, or who may be so, are of no relevance in that regard.”34 As Jégo-Quéré satisfied this new test, the Court concluded that it did have individual concern, and that its application should therefore be admissible. 2.3.1.2. Acts 4, 5 and 6: The Judgment of the Court of Justice in UPA, and the Advocate General’s Opinion and Judgment in Jégo-Quéré But hot on the heels of the CFI’s dramatic coup in Jégo-Quéré came the Court of Justice’s ruling in the case which had started it all: UPA. The ECJ refused to follow its Advocate General, and implicitly admonished the junior Court in the process. Having reviewed the CFI’s Order in UPA, which, it will be remembered from Act 1, ruled the application of the olive-growers’ association inadmissible, the Court noted that the appellant was not challenging the CFI’s findings in relation to the legislative nature of the Regulation, the inability of its members to show distinguishing features in the Plaumann sense, or its own failure to demonstrate an individual interest. In fact, UPA’s sole argument (albeit divided into four pleas) was that the CFI had erred in its appreciation of UPA’s lack of an effective judicial remedy. The Court of Justice reiterated that, in the absence of individual concern, a private applicant may never proceed against a Regulation. It accepted that private applicants were entitled to effective judicial protection, and indeed that this was a general principal of Union 33 34 Case T-177/01 Jégo-Quéré, the CFI’s judgment, Para. 23. Ibid., Para. 51. 9 law. However, it continued, with Articles 263 and 277 TFEU (as they are now) on the one hand, and Article 267 TFEU (as it is now) on the other, the Treaty had created “a complete system of legal remedies designed to ensure judicial review of the legality of acts of the institutions”.35 The ECJ agreed with the lower court’s ruling that it was up to the Member States, pursuant to the duty of sincere cooperation, to ensure effective judicial protection. Nor did the Court seem keen on the idea – referred to by Advocate General Jacobs in his Opinion - that it might have to investigate the inner workings of the relevant Member State’s justice system every time a private applicant alleged that there was no national remedy of which it could avail itself. Finally, the Court held that it was “for the Member States, if necessary, in accordance with Article 48 EU [concerning the procedures for amending the Treaties], to reform the system currently in force”36. Having poured cold water on troublesome olive oil, the Court of Justice still had to rule on the appeal brought by the Commission in Jégo-Quéré. First, it fell to Advocate General Jacobs, once again, to deliver the Opinion. Describing the ECJ’s decision in UPA as “unsatisfactory”37, he nevertheless accepted that it was “unavoidable”38, and that, “as the law now stands”39, the Commission had to succeed in its appeal. He also gave short shrift to a cross-appeal by the fishing company, that the CFI had been wrong to hold that it lacked individual concern; it had not been wrong, said the Advocate General. All that remained now was for the ECJ itself to give judgment. In a near-facsimile of its decision in UPA, the Court repeated its comments about the “complete system of legal remedies”40 provided for under the Treaty, and restated its view that effective judicial protection was a job for the Member States. Thus, even if the private applicant in question must breach domestic law to gain access to the national court, it still had no standing to bring a direct action before the European Court41. It concluded that the Court of First Instance’s interpretation of the relevant provision “has the effect of removing all meaning from the requirement of individual concern in the fourth paragraph of Article 230 EC [Article 263 TFEU as it is now].”42 The Court of Justice thus found for the Commission. With a swift dismissal of the fishing company’s cross-appeal, the CFI’s prize catch was thrown back into the sea. 2.4. The scene is set for the new wording What was becoming clear was that, amongst all possible private challengers of all possible EU measures, one group was particularly vulnerable. Defining this group is itself problematic, as one is forced to work with the same blunt descriptive tools as the Court, but in basic terms, it is the group of those private applicants wishing to challenge a general legislative act or a general non-legislative act, where the act concerned requires no 35 Case C-50/00 P UPA, the ECJ’s judgment, Para 40. Ibid., Para 45. 37 Case C-263/02 P Jégo-Quéré, the Advocate General’s opinion, Para 46. 38 Ibid. 39 Ibid., Para 47 40 Case C-263/02 P Jégo-Quéré, the ECJ’s judgment, Para 30. 41 Assuming it could not show direct and individual concern, of course. Ibid., Paras 33 and 34. 42 Ibid., Para 38. 36 10 implementation at Member State level.43 The members of this group find themselves in a double bind, owing, firstly, to the fact that the act is general and they have no means of individualizing themselves à la Plaumann, and, secondly, to the fact that it requires no implementing measures, leaving them with nothing to challenge before the Member State’s own courts, a challenge which could then have been used as a springboard to bring the matter before the ECJ via the preliminary reference procedure. Their only alternative, to force themselves before the national judge by breaking domestic law, is both unpalatable in societies governed by the rule of law, and risky, given that a reference may not be made to Luxembourg or may be unsuccessful, leaving them with possible civil or criminal liability on top of the usual cost implications of failed litigation. However, in 2002, the very year of the Advocate General’s Opinion in UPA, the CFI’s judgment in Jégo-Quéré and the ECJ’s judgment in UPA, the Convention on the future of Europe had begun work on producing a draft Treaty establishing a Constitution for Europe. Accepting the challenge set by the ECJ in UPA to “reform the system”, this Convention set about drafting a new provision to govern standing requirements for private applicants, which resulted in the adoption by the Convention of the new wording set out in section 2.1 above. Although signed by the Heads of State and Government on 29 October 2004, the Constitutional Treaty was later scrapped following negative referenda in France and the Netherlands. After a “period of reflection”, a new “Reform” Treaty was drawn up, which was formally signed and adopted on 13 December 2007, and, after a shaky ratification process, came into force in December 2009. The Reform Treaty, also known as the Treaty of Lisbon, merely reformed the existing Treaties (the EC Treaty now being renamed the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (“TFEU”)), rather than attempting to create a brand new instrument, as the Constitution had done. Nevertheless, in its judicial review provision – now Article 263(4) TFEU – the Treaty duplicated the wording selected by the Convention. The question was – what difference would this new wording make to the vulnerable applicants described above? 3. The situation after Lisbon 3.1. The provenance of the new wording One innovation of the Constitution had been the establishment of a new hierarchy of norms such as had not existed previously in EU law44. The three existing legal instruments – Regulations, Directives and Decisions – were to be replaced by four new ones - European laws, European framework laws, European regulations and European decisions. A discussion of the meaning of these terms will not be embarked upon here, as ultimately they were abandoned. However, what is important for the purposes of this paper is to note that 43 Some might argue that only those private applicants wishing to challenge a general non-legislative act, where the act concerned requires no implementation at Member State level, were vulnerable. However, that would exclude companies in the same market position as Codorniu, say, but not in possession of pre-existing intellectual property rights. It is submitted that such companies are also unfairly locked out of court under the present rules. But of course opening up the standing rules for private applicants to include general legislative acts might go too far, allowing not just those wine-producers using the word “cremant” on their labels (with or without IP rights) to challenge a Regulation reserving that word to producers in France and Luxembourg, but anyone else as well. That is why Advocate General Jacobs’ “substantive adverse effect” test has a lot to commend it, as it retains at least some element of filtration. 44 Bieber and Salomé were in fact calling for an “increased degree of hierarchy” amongst the different acts recognized by European law some fifteen years ago: R Bieber and I Salomé, “Hierarchy of norms in European Law” 1996 CMLRev 33(5) 907, 924. This is a fascinating article, pointing out some of the advantages of, but also some of the difficulties caused by, “the rather obscure systematic structure of European law”: ibid., 921. 11 the new “European regulations” were not the equivalent of the old-style Regulations. If the old-style Regulation had an equivalent in the new regime, that equivalent was the new European law. The new European regulation, however, was defined as: “a non-legislative act of general application for the implementation of legislative acts and of certain provisions of the Constitution. It may either be binding in its entirety and directly applicable in all Member States, or be binding, as to the result to be achieved, upon each Member State to which it is addressed, but shall leave to the national authorities the choice of form and methods.”45 If one considers Figure 1 below, a table of relevant adjectives used to describe legal instruments by the Court and by commentators, one can see that the word “regulation” under the Constitution would now be better described by those adjectives under Column 2, than by those adjectives under Column 1. Column 1 Legislative Normative Column 2 Non-legislative Administrative Figure 1: Relevant adjectives used to describe legal instruments by the Court and by commentators One of many layers of complexity in this story is the fact that, during the summit of mid-2007 after the so-called “period of reflection”, when the Constitution was turned into the Lisbon Treaty, some provisions retained their Constitution-era wording, while others reverted to their pre-Constitution state. In other words, some of the new jargon was kept in place, while other parts were junked. The significance of this for the present essay is that, while the fourth paragraph of the judicial review provision kept its “new” phraseology, the part of the Treaty dealing with legislative measures – the very things which were to be reviewed – returned to its original nomenclature, that is, Regulations, Directives and Decisions. The Heads of State and Government had thus left the code, but taken away the code-book. The key phrase, “a regulatory act which is of direct concern to them and does not entail implementing measures”, was admittedly still difficult to decipher even before the downfall of the Constitution. As Arnull pointed out at the time, “Although Part I of the draft Constitution contains an elaborate hierarchy of acts, the crucial term “regulatory act” is nowhere defined.”46 However, that was nothing as compared to the difficulty facing those trying to decipher the phrase once it had been transplanted into the Reform Treaty, where the “hierarchy of acts”, if it could even be called a hierarchy, was the same one from 1957. Critically, the noun “Regulation” was back in its old home47, invoking legislation and, for that matter, generality as it had always done, so that its adjectival form – regulatory – should now by rights be a synonym, not an antonym, of “legislative” and “general”. Put simply, the Regulation had returned from column 2 to column 1. 45 Article I-33(1), fourth paragraph, of the Treaty establishing a Constitution for Europe [2004] OJ C310/1. A Arnull, “A Constitutional Court for Europe?” [2003-4] 6 Cambridge Yearbook of European Legal Studies 1, 28. The same point is made by Lenaerts and Corthaut: K Lenaerts and T Corthaut, “Judicial Review and European Constitutionalsim” in T Tridimas and P Nebbia (eds), European Union Law for the Twenty-first Century: Volume 1 - Constitutional and Public Law/ External Relations (Hart, Oxford 2004) 43. 47 The second paragraph of Article 288 TFEU, formerly Article 249 EC, and before that Article 189 EC. 46 12 As will by now be clear, what this story boils down to is a number of sets of antithetical labels – general versus individual, legislative versus non-legislative, State-executed versus selfexecuting. The allocation of these labels amongst the four new legal instruments under the Constitution – European laws, European framework laws, European regulations and European decisions – was already problematic as a different result seemed to be reached for every set, for example, European laws and European framework laws might have been considered legislative, while European regulations and European decisions might have been considered non-legislative, but European framework laws, European decisions and European regulations might all have been considered as State-executed, while only European laws would have been considered as self-executing. This difficulty of matching labels to laws has only been exacerbated by the return to the Treaty of Rome’s original trio of legal instruments – the Regulation, the Directive and the Decision. As the Commission put it in another context, there are “serious problems of demarcation”48. Biernat offers a nice account of the genealogy of the provision, as it moved through the various stages of the Convention, although unfortunately her account ends before the Lisbon generation. She confirms that the Constitutional judicial review provision (Article III-365(4) in the final version, although Article III-270(4) when she was writing) was intended to tally with the provisions detailing the different types of legislative instrument (Articles I-32 to I-36, later I-33 to I-37): “The Convention has chosen words “regulatory act” to reflect the new hierarchy of legal acts of the Union to be established by the Constitution. The question of amendment of Article 230(4) is closely linked with this reform, introducing the distinction between legislative and non-legislative acts.”49 Tridimas, also writing in the days of the Constitution, is of the opinion that the original wording of the fourth paragraph did not provide sufficient legal protection for the individual, but describes the new wording as only a “limited liberalisation” 50; he regrets the use of the term “regulatory act” and thinks that the requirement for individual concern should be dropped for all types of act. Of his proposed formula, he comments: “It avoids, in particular, arguments as to whether an act is, or should be, regulatory rather than legislative in nature. As Article 270(4) currently stands, it encourages argument that an act which has been adopted in the form of a legislative act is, in fact, a regulatory one. The new formulation re-introduces uncertainties similar to those which marred the case law in the 1960s when the distinction between a legislative and administrative acts [sic] was perceived important for the purposes of locus standi.”51 The terms “legislative” and “regulatory” are used as antonyms here; “regulatory” means “administrative”. But herein lies the crux of the problem. The term “regulatory” cannot mean “legislative” and “non-legislative” at the same time. The fact therefore has to be faced that the meaning of this word has shifted, from being a synonym of “legislative” in the days 48 Case C-101/01 Criminal proceedings against Bodil Lindqvist [2003] ECR I-12971, at Para. 36. E Birenat, The Locus Standi of Private Applicants under article 230(4) and the Principle of Judicial Protection in the European Community (Jean Monnet Working Paper 12/03, NYU School of Law, New York 2003) 52, Biernat’s emphasis, footnotes omitted. 50 T Tridimas, “The European Court of Justice and the Draft Constitution: A Supreme Court for the Union?” in T Tridimas and P Nebbia (eds), European Union Law for the Twenty-first Century: Volume 1 - Constitutional and Public Law/ External Relations (Hart, Oxford 2004) 123. 51 Ibid., 125 (Tridimas’ emphasis). 49 13 before the Constitution, to being an antonym of it in the Constitution itself. The question that leaves is, what does it mean today? With the Lisbon Treaty having one foot in the Constitution and one foot out, the question is not easy to answer. 3.2. The meaning of “regulatory” Dashwood and Johnston, for example, seem uncharacteristically confused52. After giving the new wording of the fourth paragraph, they continue: “This is a welcome recognition of the possibility that even a genuine Regulation can nevertheless have an impact upon the position of individuals such that it can be challenged in an action for annulment, even if the measure is one of “general application” and without the need to satisfy the test of individual concern.”53 This would seem to be a clear assertion that, in their opinion, the term “regulatory act” means, to all intents and purposes, “Regulation”. However, as they proceed to analyse the Constitution’s provisions describing the different types of legislative act, they appear to talk themselves out of this. Under the Constitution, they correctly note, the new name for what were traditionally known as “Regulations” was to be “European laws”, while the term “European regulation” was thenceforth to refer to “a non-legislative act of general application for the implementation of legislative acts”54. Thus, they deduce: “the key question for assessing the impact of the new wording… is what scope will be given to the category of measures that correspond to the term “regulatory acts” (which presumably can only include European regulations under Art I-33(1), 4th subpara). This formulation clearly excludes the possibility of individual challenges to European laws…”55 The use of the fourth paragraph by non-privileged applicants to challenge old-style “genuine Regulation[s]”56, but now without needing to show individual concern, was thus ruled out, not in.57 De Witte takes the term “regulatory act” to mean non-legislative acts, that is, “acts not adopted in accordance with the ordinary or special legislative procedure”58: “The Court will thus probably still require direct and individual concern for legislative acts of general application, while individual concern will no longer have to be shown 52 A Dashwood and A Johnston, “The institutions of the enlarged EU under the regime of the Constitutional Treaty” Common Market Law Review 2004, v. 41, n. 6, December, 1481. 53 Ibid., 1508. 54 These matters were dealt with at Article I-33(1) of the Treaty establishing a Constitution for Europe [2004] OJ C310/1. 55 Dashwood and Johnston, supra n 52, 1509 (emphasis added). 56 Ibid, 1508. 57 It would be otherwise if Dashwood and Johnston had meant by the phrase “genuine Regulation” on 1508 the new type of regulation envisaged by the Constitution. But this is unlikely given that the phrase “genuine Regulation” is so firmly rooted in the pre-Constitution case law, where of course the issue was whether a given Regulation was “genuine”, or a Decision in disguise. Further, why, if they were referring to a brand new type of instrument never considered judicially before, would the reworded paragraph represent a “welcome recognition” of anything at all? 58 F de Witte, “The European Judiciary after Lisbon” 15 MJ 1(2008) 43, 47. 14 by applicants for whom no alternative national remedy exists and who are thus obliged to infringe national law before an executive Union act can be challenged.”59 This contrasts with Girón Larrucea, who holds that “Regulatory acts have a general character, as a result of which they should not directly affect an addressee, except for the sole reason that they are one of the participants in a certain area of activity for the general regulation of which the act was adopted.”60 On Girón Larrucea’s logic, an applicant like Mr Plaumann would no longer fall at the individual concern hurdle, since regulatory acts are now attackable on the sole condition that the challenger can show direct concern. In Plaumann itself, the Court never expressed a view on direct concern, by dealing with individual concern – which it of course found absent in Mr Plaumann’s case – first. However, Advocate General Roemer was of the opinion that Mr Plaumann also failed the direct concern test, Member States having to avail themselves of the authorization in question before an importer such as Mr Plaumann became involved, thus breaking the chain of causation between the Commission and the applicant. If the Court were to follow the Advocate General on this, a future Mr Plaumann would apparently be no better off. Meanwhile, on De Witte’s logic, a future Mr Plaumann would be in exactly the same position as his predecessor was in 1963. But the real concern should perhaps not be that this linguistic confusion may allow too few private challengers to succeed, but too many. If one takes the example of a company like Codorníu, affected by a generally applicable Council Regulation perhaps to the point of having its very business threatened, and wishing to challenge this under Article 263(4), into which class – using the schemata in section 2.1. above – would the contested measure now fall? Under the old wording, Regulations having been specifically referred to in the text of the provision, only class (1c) would have been in the running. Ordinarily, the applicant would have needed to show (in addition to direct and individual concern) that the Regulation was a disguised Decision to bring it within class (1c), although of course in the Codorníu case itself, for the reasons explained above, this requirement was dispensed with. What is the position under the new wording? On the one hand, if the phrase “regulatory act” is simply taken to mean “Regulation”, then class (2c) would seem to be the obvious choice, only this time the applicant would only need to show direct concern to succeed in his challenge. A company like Codorníu would now succeed even if it did not have pre-existing intellectual property rights in the words “gran cremant”. This new wording thus goes beyond a mere codification of Codorníu by not only allowing true Regulations to be attacked, where individual concern could be shown, but also where it could not. And if one assumes – arguendo – firstly, that all Regulations clear the direct concern hurdle by their very nature, and, secondly, that no Regulation requires implementing measures, then this would certainly seem to throw the doors of the Court very wide open indeed. To return to the argument made earlier, the subjective element within the class has been removed: all Regulations are challengeable, by anyone. 59 Ibid., footnote omitted, De Witte’s emphasis. JA Girón Larrucea, El sistema jurídico de la Unión Europea: la reforma realizada en el Tratado de Lisboa (Tirant lo Blanch, Valencia 2008) 267 (author’s own translation). Although “addressee” is the only definition given for “destinatario” in the Collins Spanish-English dictionary, this author suspects that, since a general act by its very nature is unlikely to have been addressed to any natural or legal person in particular, Girón Larrucea meant this more in the sense of “the party who is, or finds themselves, bound”. 60 15 On the other hand, if the term “regulatory act” does not mean Regulation, or at least not automatically, then the choice of class is more difficult. The replacement of the old word “decision” with “act” means that the second of the classes – class (2b) – is now a contender in a way its earlier counterpart – class (1b) – could not be. Regulations are addressed to the Member States, which counts as “another person” in the existing case-law. The company could therefore attack the (true) Regulation, as before under class (1c), Codorníu version, if it could show direct and individual concern. The doors opened in the previous paragraph would close again. But this would mean that the new third class – class (2c) – was intended for some other purpose. Perhaps it was intended to be a fluid and flexible class to aid the “vulnerable” applicants identified in section 2.4. above, who – assuming “regulatory” now means something along the lines of “non-legislative” or “administrative” – would be in a Jégo-Quéré/UPA-type situation, unable to challenge an administrative act on the part of the executive (precisely the sort of act which judicial review provisions should enable to be challenged), simply because of its generality and the problems that that brings with it under the Plaumann doctrine. And yet that description could well cover the hypothetical company under consideration too. Which class should the Court then opt for – the one that obliges the challenger to show individual concern, or the one that does not? If the Court adopts a species of the German günstigkeitsprinzip (principle of advantage, or favourability principle), allowing the challenger to take advantage of the more favourable of the two options, then the second class – class 2(b) – loses, if not all, then at least some of its purpose, and the floodgates start to reopen.61 If not, the Court may still face the unenviable task of explaining to a frustrated private applicant that a Regulation is not regulatory. 4. Conclusion Perhaps the last word should be given to Konrad Schiemann, who, as British judge at the Court of Justice, is almost certainly going to be among the first to interpret the new provision. In 1990, then a judge at the English High Court, he wrote a very interesting piece weighing up the advantages and disadvantages of a more open approach to locus standi. Among other things, he commented: “There is in my mind no self-evident necessity to have the same locus standi rules, nor indeed the same purpose behind the locus standi rules, in all branches of litigation. The task of formulating general principles becomes more complex the more you seek to embrace by one rule, particularly if the rule has different objectives in different cases. That problem can only be solved by making the rules very complex or very vague. The problem is side-stepped to a degree by having different rules, if thought desirable, in different branches of litigation. Further, there is no particular reason why the rules as to locus standi in judicial review proceedings should be identical whatever the relief sought. I see nothing necessarily wrong in giving someone standing for the purpose of a declaration but not giving him standing for the purpose of mandamus.”62 61 It should be noted that, in Germany, the principle only applies in the context of employment law, allowing employees to have the benefit of terms in an employment contract where these are more favourable than regulations laid down in higher-ranking norms of law. A similar principle may be found in UK employment law, for example, if an employee has a contractual right to paternity leave as well as his statutory right, he may take advantage of whichever is the more favourable. However, variations on the principle can be seen in many branches of law all over the world. An interesting example is in the area of energy law: s. 10(7) of the Energy Charter Treaty. The principle has been mentioned by an Advocate General at the Court of Justice, although strictly within its employment law context: Case C-271/08 European Commission v Federal Republic of Germany (ECJ 15 July 2010) – see Opinion of AG Trstenjak, footnote 113. 62 K Schiemann, “Locus standi” P.L. 1990, Aut, 342, 343. 16 This plea for flexibility is extremely wise, and it is a shame that the EU’s legislative draughtsperson did not take such a creative, variegated approach to the redrafting of the fourth paragraph. As things stand, it appears that the case of the mystery measures is still a long way from being closed. 17