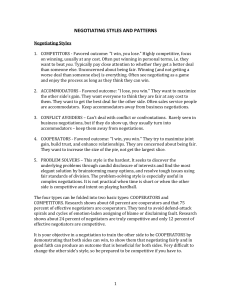

One can make different assumptions on the information players

advertisement