(excerpted from the Report of the Area One Design Committee, 2/19

advertisement

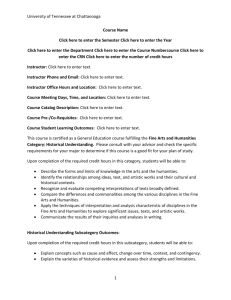

(excerpted from the Report of the Area One Design Committee, 2/19/97) RATIONALE OF THE AREA ONE PROGRAM LEGISLATION We recommend that Stanford's revised first-year Area One course sequence, Introduction to the Humanities, require students to study intensely -- from various perspectives in the humanities (the field being broadly defined) and in important texts from diverse sources and different times and places taught by diverse faculty members -- significant ideas, values, issues, intellectual traditions, problems, myths, imaginative constructs, and desires that resonate in human experience and history, in our dynamic modern American culture, and in this academic community. That means that the requirement will feature the study of works and subjects that have cultural importance by virtue of their influence, enduring heritage, power, relevance, representative significance, potential to shape the future, aesthetic appeal, and/or arresting mode of expression, and ability to inspire fresh scholarship from many perspectives. The Area One Requirement shall consist of a one-quarter, team-taught course providing a general introduction to humanistic inquiry, followed by two-quarter course sequences of more specialized study exploring particular themes, issues, forms of experience, modes of expression, and/or bodies of knowledge. With regard to the specific implementation of the program and the legislation we are proposing, we specifically recommend: 1) that the best and most dynamic teachers in the humanities continue to be encouraged and attracted to teach in the Area One course sequences and that even more University effort and resources be mobilized towards this goal (In the first quarter course, the process of putting it together would require faculty from different disciplines to discuss, agree, and set up particular goals for the course and plan, articulate and exchange ideas about how these goals might be reached; for the two-quarter sequence, the University must continue to recruit faculty in several departments or faculty from similar areas of interest and expertise); 2) that small group instruction, since it is so central to the program's success, must be increased from at least two hours per week (as is now mandated) to at least three hours per week in at least two meetings, and that the size of the sections should not exceed fifteen students; 3) that the discussion group leaders should all have earned the Ph.D., that their status should be upgraded to the standing of a three-year, term-limited Assistant Professor, with the possibility of a one-year reappointment, but no more, and that, following the 1 recommendation of the 1988 CIV legislation and the model of some present CIV tracks, these Ph.Ds, competitive in the job market, should be highly qualified, outstanding post-docs identified and chosen for their excellence, promise and productive capacities in a national search; 4) that the Freshman Writing Requirement should be integrated with the Area One Requirement whenever it can be done in accordance with the positive Proposal to the Provost from the Writing and Critical Thinking Program for "Linking the Writing Requirement with Area One and Freshman Seminars" (we find evidence that when both requirements are merged the potential academic and intellectual benefit for students is substantially increased); 5) that the Area One Governance Committee and its chair must be actively involved in recruiting faculty to teach courses for Area One; in implementing the requirement, legislation, and program; in working with departments in the hiring of post-docs; in evaluating courses and teachers; and in coordinating Area One with other segments of Stanford Introductory Studies. We believe a way to focus and implement the goals of Area One is to define the requirement as something even more inclusive than Cultures, Ideas, and Values (CIV) and at the same time possibly more manageable for practical instruction: namely, an introduction to the humanities and inquiries into the nature of human being. We support most of the goals and the spirit of the present CIV legislation (and specifically we support its aim of making students aware of the range of human experience and cultures), and we seek, by reforming the structure of the course sequence, to promote more opportunity for faculty creativity and innovation and more choice for the students in satisfying the requirement. For good or ill, many students at the end of the twentieth century ask, "why should I study the humanities or culture, ideas, and values?", "how should I study them?", "why study the history of the past, the history of thought, the origins of culture?", "why study the arts and literature?", "what is civilization?", and "what is human identity?" For them, these questions no longer have self-evident value or answers, do not seem worthwhile, and can even seem meaningless. That does not mean that this scholarly area and its subjects have become less vital; rather, student perceptions are changing, and the nature of inquiry in the humanities, is developing and growing more complex as it deals with proliferating materials, new approaches to knowledge, and new forms of experience. We think, therefore, that the relevance and expanding nature of the humanities must be explicitly taught to all Stanford students in challenging courses of new design combined with the effective modes of the present program. We see the need to promote and teach awareness 2 of the analytical, aesthetic, and ideological issues that the developing study of the humanities involves. The dictionary definition of the "humanities" this century has evolved from "learning or literature concerned with human culture, a term including various branches of polite scholarship, as grammar, rhetoric, poetry, and esp. the study of ancient Latin and Greek classics," through "the study of literature, philosophy, art, etc., as distinguished from the social and physical sciences" to the most recent definition in Merriam Webster "the branches of learning that investigate human constructs and concerns as opposed to natural processes," a definition which certainly includes anthropology, feminist studies, religious studies, ethnic studies, and political theory as well as literature, art, classics, and history. Our proposal recognizes the changes in the field of the humanities. Students need to confront directly the problems and the power of the developing humanistic enterprise in modern culture. Like CIV, the revised Area One courses will focus on the need to understand the complexities of human interaction as represented and expressed in compelling language; the need to focus on evolving and shifting ways of looking at human constructs and texts and see how humanistic inquiry makes them relevant to a culture and its various peoples; and a need to teach and make students understand the relevance of the past and how the past is constituted in the present. It will also directly address what it often treats implicitly or tangentially now: the need for a general introduction to the traditions and developing functions of humanistic inquiry and the subject matter of the humanities; the need for explicit inquiry into and knowledge of humanistic ways of looking at experience; and the need to study the motives and aims of various peoples engaged in the work of the humanities. The revised Area One Requirement must stress the need and importance of teaching entering college students to read complex and significant works closely, carefully, and patiently. Again and again, in the survey on CIV we conducted of graduating seniors, the gist of this remark appears: "Close readings of texts should be further emphasized even at the expense of the number of texts read." The opinion motivating that statement was almost universal in the respondents. Here is just a small sample of typical answers to our question on "how to make CIV better": "Fewer texts to be studied in depth," "fewer works in more depth," "CIV needs to focus on fewer, more important works," "by about the middle of the 2nd quarter, students give up on reading it all -- it would be better for the faculty to select the more important readings & assign only those." That is why we recommend focusing instruction on intensive, various readings of a limited number of important texts in the first quarter of Area One. We favor for the three-quarter Area One Requirement the "one-quarter, two-quarter" pattern because this structure offers basic grounding in the study of the humanities from 3 multiple perspectives, followed by a variety of course sequences in major subjects and concerns in the humanities. It allows the process of instruction to move from the general to the particular and thematic in humanistic inquiry. It offers close, common focus on a few representative texts, chosen from different traditions, interpreted in light of key, but different disciplinary approaches in the humanities (e.g., aesthetic, historical, and philosophical) and then it moves to more diversified subjects studied from more specific approaches. And students would have some choice during autumn quarter in selecting their two-quarter course sequence for Winter and Spring. The principle that guides the introductory course is the principle of beginning with close reading from various points of view and for multiple purposes: If students can read thoroughly, from many perspectives, a single rich and complex work, they can learn to do the same thing with other texts. The point of an introductory humanities or CIV course ought not be illusory coverage, but really learning how to approach, see and feel the radiating qualities of a significant work and then applying that knowledge to new texts and subjects. The great humanist Henry David Thoreau wrote "Time is but the stream I go a- fishing in," and -- to continue the metaphor -- the principle of this requirement is not to give the students examples of each and every kind of nourishing fish, but to teach them the art of fishing, the reason for fishing, the means of recognizing and judging fish, and then to take them out fishing. Once the rationale of a "culture" or "civ" course was to read particular works forming the core of Civilization, but with the assault on cultural parochialism and superficiality, a better one seems to us a broad-gauged study of what constitutes the humanities, how and why they matter and change, and what humanistic inquiry is. Popular conceptions of "culture" or "civilization" courses now suffer from two opposite stereotypes, both ultimately shallow: that such a course tends to feature the out-of-date literature of an oppressive white patriarchy ("dead white males"), or, alternatively, that such a course should present the indispensable authors of Western Civilization -- or "civilization" generally -- who form a -- or "the" --" canon" and/or our cultural history. Our committee, then, is alive to three basic criticisms of our proposal: 1), that our recommendations, because they eschew some of the prescriptive language of the 1988 legislation (SenDoc#3307) and set up a set of broadly based criteria that the Area One Requirement should meet, might be misconstrued as an abandonment of the opening to diversity and a return to a course with a prescribed canon that supposedly constitutes culture; 2), that, from an another point of view, in failing to prescribe the content of the course and a common core of texts, we are abandoning the heritage of the past and the responsibility of teaching the foundations of civilization and culture that an educated person needs to know; 3), that, in the "1 + 2" structure, we will lose continuity, historical focus, and a comprehensive sense of human development. 4 To the first criticism, we say that we strongly support the opening to study cultural breadth and a new inclusiveness enacted in the Area One Requirement, and we can not conceive of, and would not sanction, an introductory course sequence in humanistic study that didn't include, for instance, multicultural perspectives, attention to gender, race, religion, social identities, and significant texts by women and men of various cultures and ethnicities. We charge the Area One Governance Committee to note carefully the language of the new legislation and to insure that the spirit and principle of inclusiveness established by the 1988 Area One Requirement is maintained. To the second objection we say that by recommending an introduction to, and forms of, inquiry into the humanities, we intend the teaching -- through representative texts, chosen carefully by individual faculty members under the oversight of the Area One Committee, for the significance of their content, rather than through a flurried attempt to choose and cover "the" great books and "our" or "others'" cultural history -- of precisely the foundations of culture that an educated person at the end of this century needs. We mean to ensure that the wording of the legislation, the judgment of the faculty, and the oversight of the Area One Governance Committee will insure the study of major texts of enduring influence, power, and pedagogical relevance that help make students aware of their complex cultural and humanistic heritage. In the present stage of humanistic inquiry, reducing civilization -- or the humanities -- to a single book list (think how many "great," "seminal," "indispensable" books there are) seems both arbitrary and impossible. The committee intends to move away from the specification of content in so far as possible. In this, we aspire to something analogous to the science requirements, in which the University does not specify, say, statistics or calculus, but math; not biology or physics or chemistry but natural science. Thus, while we certainly need to provide examples of potential courses, we have decided that the specifications need to be put in more general terms in order to give the faculty freedom to engage significant issues as they see them and to respond to changing needs on the part of the students. With freedom goes responsibility and trust in colleagues to do a good job as they devise courses to meet the specifications and live up to the spirit of the requirement. To the third criticism, we say that we hope the benefits of basic instruction in humanistic inquiry outweigh any loss in continuity, but that sequences can be designed with continuity; that historical focus can be stressed in some courses, that historical focus in the present CIV varies greatly, as it will in the new Area One; and that whether comprehensiveness is illusory or not, the grounding in modes of humanistic inquiry can certainly be an effective way to study human development and the relationship of past and present. It is time to redefine the core of an introduction-to-the-humanities, "CIV"-type course: It is not a fixed content, a token core list of authors and works that nobody can quite agree on, or "the common intellectual experience of broadening students' understanding of 5 culture, cultural diversity and the process of cultural interaction" (though it could and should foster such experience), but the study of the making and manifold understanding of important articulations and expressions -- significant in the historical and aesthetic memory that makes the future -- of what it is, and how many ways there are, to be human. 6