Background

advertisement

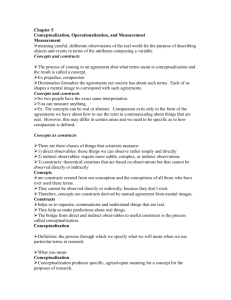

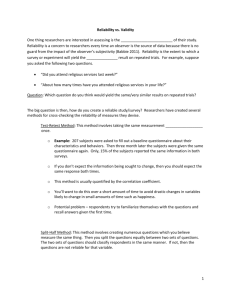

Background Conceptualization is the process by which researchers specify precisely what they mean when they use particular terms. The process begins with the clarification of abstract mental images. Concepts are the words or symbols in language that we use to represent those mental images. The end product of the conceptualization process is the specification of a set of indicators of what we have in mind, indicating the presence or absence of the concept we are studying. Dimensions are specifiable aspects of a concept. Although the researcher’s observations and experiences are real, concepts are only mental creations. The terms associated with concepts are merely devices created for communication. The process of regarding as real things that are not is called reification. Great care must be taken here since the researcher must discover what real meanings exist and what constitutes a genuine measurement of them. The design and execution of criminal justice research require clearing away the confusion over concepts and reality. Three kinds of definitions are distinguished: real, conceptual, and operational. A real definition is a statement of the essential nature and attributes of an entity. A conceptual definition is a working definition specifically assigned to a term. An operational definition spells out precisely how the concept will be measured. Describing how to obtain actual empirical measures begins with operationalization: the process of developing operational definitions. The next step is to make the measurements. Measurement is the process of assigning numbers or labels to units of analysis in order to represent conceptual properties. One way to think of measurement is to compare the process with scoring. The conceptualization and operationalization processes can be seen as the specification of variables and the attributes composing them. Every variable should have two important qualities. First, the attributes composing each variable should be exhaustive, meaning that researchers must be able to classify every observation in terms of one of the attributes composing the variable. Second, attributes composing a variable must be mutually exclusive, meaning that researchers must be able to classify every observation in terms of one and only one attribute. Variables may represent different levels of measurement. Variables whose attributes have only the characteristics of exhaustiveness and mutual exclusiveness are nominal measures (examples: gender, race, city of residence, college major). Variables whose attributes may be logically rank-ordered are ordinal measures (examples: occupational status, crime seriousness, fear of crime). When the actual distance that separates the attributes composing some variables does have meaning, the variables are interval measures (example: standardized intelligence tests). In ratio measures, the attributes that compose a variable, besides having all the structural characteristics mentioned previously, are based on a true zero point (examples: age, number of prior arrests, length of sentence). In your text, the Putting It All Together feature, “What’s a Police Activity,” provides an excellent illustration of the efforts to develop a measure (police activity), including the execution of conceptualization, conceptual definition, operational definition, and making observations in the field. The key standards for measurement quality are reliability and validity. Reliability is a matter of whether a particular measurement technique, applied repeatedly to the same object, will yield the same result every time. Measurement reliability is often a problem with indicators used in criminal justice research. Consequently researchers employ a number of techniques for dealing with it. The test-retest method highlights the advantages of making the same measurement more than once. Researchers must also be aware of interrater reliability: It is possible for measurement unreliability to be generated by research workers, such as interviewers and coders. The split-half method highlights the value of making more than one measurement of any subtle or complex social concept (such as prejudice or fear of crime). Validity means that an empirical measure adequately reflects the meaning of the concept under consideration: Are researchers really measuring what they say they are measuring? Researchers have a variety of ways of dealing with the issue of validity. Face validity “makes sense,” and there are many concrete agreements among researchers about how to measure certain basic concepts. Content validity refers to the degree to which a measure covers the range of meanings included within the concept. Criterion-related validity compares a measure to some external criterion. Construct validity is based on the logical relationships among variables. Composite measures are frequently used in criminal justice research. The FBI crime index is a good example of a composite measure of crime. Researchers combine variables in different ways to produce different composite measures. The simplest of these is a typology, sometimes called a taxonomy.