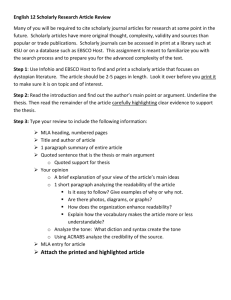

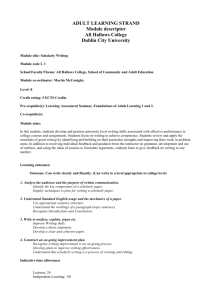

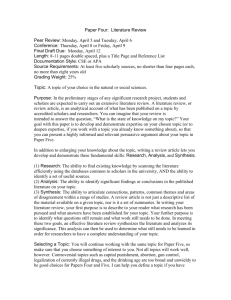

Research Paper Information

advertisement