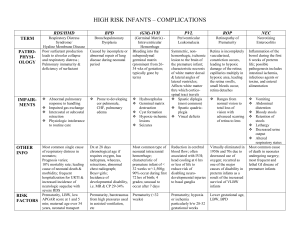

Persistent ductus arteriosus The ductus arteriosus is a blood vessel

advertisement

Persistent ductus arteriosus The ductus arteriosus is a blood vessel which links the pulmonary artery with the aorta during the foetal period. During the foetal period, the vessel is kept open by prostaglandins because circulation through the lungs is then not necessary. After the birth, the blood vessel closes quickly, usually during the first day, but the closure is often delayed in premature children. In Sweden, approx. 60 per cent of the extremely premature infants are treated for persistent ductus arteriosus (PDA) and the shorter the length of the pregnancy, the more common it is [4, 26]. When the flow resistance in the pulmonary circulation is reduced, with PDA there is a leakage of blood from the aorta to the pulmonary artery (known as a left-right shunt). If the shunt blood flow becomes significant, symptoms appear in the form of greater breathing and heart rates, a greater need for oxygen and sometimes respirator-dependent. The child can also suffer heart failure, apnoea (interrupted breathing), a drop in blood pressure, kidney failure and digestion problems. PDA has been associated with intraventricular brain haemorrhage (IVH), necrotising enterocolitis (NEC, inflammation of the bowel) and chronic lung disease (bronchopulmonary dysplasia, BPD) [64]. Although PDA is common and can have significant consequences for the child, the scientific support is unclear when it comes to the most suitable diagnostics and treatment [65]. As a rule, the diagnostics are based on ultrasound examinations of the heart (echocardiography) but there are no uniform criteria for when PDA becomes significant and must be treated [66, 67]. PDA can be closed pharmacologically or surgically, but the treatment has been questioned because spontaneous, delayed closure of PDA is common [64, 68]. Pharmacological treatment is also less effective among the extremely premature infants than in the more mature children [69]. Preventative measures The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare’s assessment o o The preventative measures for persistent ductus arteriosus (PDA) ought to include the treatment of pregnant women threatened with premature birth with corticosteroids because, as well as effects on lung immaturity, it also reduces the occurrence of significant PDA. Prophylactic closure of ductus arteriosus (with medicines or surgery) is not recommended. The assessment is based on systematic charting. In order to prevent significant PDA, intervention ought to begin before the birth or during the first day of life. Treatment with antenatal (administered CARE OF CHILDREN WHO ARE BORN EXTREMELY PREMATURELY THE NATIONAL BOARD OF HEALTH AND WELFARE 1 before the birth) corticosteroids is recommended for pregnant women threatened with premature birth because it has been shown to reduce the occurrence of significant PDA in children who are born prematurely, even if not all scientific studies have been able to show this effect [11, 70, 71]. Corticosteroids reduce the sensitivity to prostaglandins which otherwise keep the ductus arteriosus open [72-74]. Where extremely premature infants are concerned, prophylactic treatment with medicines has been shown to reduce the occurrence of significant PDA as well as reduce the need for surgical duct closure. However, there is a risk of side effects and unclear safety aspects. Nor has it been shown that prophylactic treatment lowers the mortality rate or improves the psychomotor development in the long term [75-78]. The treatment cannot therefore be recommended at the moment. Prophylactic duct ligation (within 24 hours of the birth) in children with an extremely low birth weight (less than 1 000 g) has not been well studied. Studies have shown that with the operation there was no difference in mortality, severe pre-maturity retinopathy (ROP) or serious IVH compared with the standard treatment. The occurrence of NEC did fall on the other hand. The scientific support as to whether prophylactic duct surgery is linked to the development of BPD is not unequivocal [79-82]. Not cutting the umbilical cord until 30-120 seconds after the birth and early CPAP treatment (continuous positive airway pressure) facilitate the circulation adaptation at the birth and both of these interventions have been shown to reduce such ill-health which is also linked with PDA [14]. PDA diagnostics The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare’s assessment o PDA diagnostics ought to take place using echocardiography where the first examination is done within one to three days. The assessment is based on consensus between the chairpersons of the expert groups. Echocardiography is the crucial diagnostic tool and all extremely premature infants ought to undergo an ultrasound of the heart to assess PDA, the first time within one to three days of the birth. The clinical picture and x-ray finds can also be important in terms of diagnosing and assessing PDA. Low diastolic blood pressure can be a sign of PDA, as can heart murmurs at the time of auscultation and brisk peripheral pulses, particularly early on in the course of events. The echocardiographic assessment is a qualified task requiring knowledge and experience. The size of the ductal shunt depends on the duct width as well as the pressure and resistance conditions in both the pulmonary and systemic circulation, which complicates the assessment. The examination conditions are also often difficult with very limited echocardiographic windows. An important 2 VÅRD AV EXTREMELY FÖR EARLYT WHO ARE BORN children SOCIALSTYRELSEN aspect of the diagnostics is also that a ductus-dependent heart defect needs to have been precluded before with any duct-closing treatment can be relevant. Despite a large number of studies within the field, both strong scientific support for or consensus surrounding the diagnostic criteria are absent [2, 4, 8]. However, the following echocardiographic criteria can be used as signs of haemodynamically significant PDA: • • • • Duct width exceeds 1.5 mm. Left atrium is enlarged, which can be measured using the diameter of the left atrium (LA = left atrial) and the aortic root (Ao = aortic). An LA/Ao quota greater than 1.5 is a sign of a significant shunt and values exceeding 2 indicate a severe shunt. The child has low or reversed diastolic blood flows in the descending aorta, mesenteric artery or cerebral artery (a strong indication). There is a diastolic forward flow in the pulmonary artery branches. An end-diastolic velocity exceeding 0.2 m/sec is a sign of a significant PDA, and a velocity exceeding 0.5 m/sec indicates a severe shunt. A duct examination usually also includes an assessment of the size of the left chamber. However, for the extremely premature infants, there is currently no information on the reliable normal values. In recent times, bio markers such as pro-BNP, a peptide that is excreted from the myocardium when loaded, have started to be used in the assessment [83]. However, experiences and the scientific support are currently insufficient to give any recommendation. Treatment of PDA The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare’s assessment • Early treatment of PDA ought to be considered for the occurrence of one or more echocardiographic criteria and clinical symptoms of significant PDA. If there is intervention, o pharmacological treatment with Ibuprofen should be used as a first choice for haemodynamically significant PDA; o surgical treatment (ligation of PDA) should be used restrictively, but can be considered if therapy fails, there is a late recurrence or if there is a contraindication for pharmacological treatment. The assessment is based on systematic charting and consensus between the chairpersons of the expert groups. PDA treatment means an intervention that usually begins 1-14 days after the birth and which aims to put an end to symptomatic PDA. Pharmacological or surgical closure of the ductus constitutes the basis of the treatment arsenal. The proportion of those who do not respond to pharmacological treatment is higher among children with a lower gestational age (level of maturity). The spontaneous PDA closure rate is also at its lowest in this group. CARE OF CHILDREN WHO ARE BORN EXTREMELY PREMATURELY THE NATIONAL BOARD OF HEALTH AND WELFARE 3 As well as pharmacological and surgical treatment, other interventions can also have an effect. CPAP treatment has low scientific support when it comes to closure of the PDA, but is supported by physiological knowledge and tried and tested experience. Fluid restriction has some support in observational studies and can be considered if it is possible to ensure adequate nutrition. Loop diuretics can impair ductus closure and these medicines ought therefore to be used only for children with clear clinical signs of over-circulation in the lungs and other signs of acute heart failure [84-87]. Blood transfusion also does not facilitate the closure of the PDA and therefore cannot be recommended [88]. Pharmacological treatment with cyclo-oxygenase inhibitors Pharmacological treatment of PDA currently takes place using non-selective cyclooxygenase inhibitors. Ibuprofen is recommended as the first choice preparation for PDA before Indomethacin, even if the preparation is comparable as regards the effect on the PDA (three out of four children respond with closure of the PDA), treatment failure, recurrence and PDA requiring surgery (approx. 10 per cent) [89]. The recommendation is based on Ibuprofen’s more favourable side effects profile (lower risk of NEC, oliguria and kidney impairment) [89-91]. Ibuprofen is given intravenously, usually for three days (one dose per day) [92, 93] and after this treatment, another round of treatment may be appropriate. There is some scientific support for a second round of treatment leading to the closure of the ductus arteriosus [94-96]. The clearance of Ibuprofen increases relatively rapidly with the child’s age and a higher dose may then be more effective [97-99]. Enteral (through the gastrointestinal tract Ibuprofen treatment appear to be just as effective as intravenous [89], but enteral administration can increase the risk of gastrointestinal haemorrhage [76]. Early pharmacological treatment of PDA (during the first day of life) has not been shown to be able to reduce serious neonatal morbidity such as BPD, NEC or ROP compared with later treatment (at five to seven days of age) [100]. Surgical treatment One in four children who were part of the EXPRESS study (extremely preterm infants in Sweden study) was operated on for PDA. The operation took place at a median age of 18 days after the birth, and the reason in 65 per cent of the cases was that pharmacological duct closure had failed. The remaining proportion of the children was operated on as the primary option. An examination of all children in EXPRESS who were treated surgically for PDA showed that the nutrition was inadequate at the time of the operation [101]. Surgical treatment of PDA can be considered if therapy fails or there is a recurrence following pharmacological treatment. Surgical treatment may also be appropriate if the child shows symptoms which mean that pharmacological treatment may be considered to be relatively or fully contraindicated (greater tendency to haemorrhage and recent or ongoing internal haemorrhage in the brain or the gastrointestinal tract) [64]. Where there is IVH grade I (milder haemorrhage), repeating the ultrasound examination of brain after one day is recommended and, if the haemorrhage remains unchanged, it is not considered to constitute a contraindication for pharmacological treatment. If blood is shown in the ventricular system, the assessment ought to be assessed more cautiously as regards 4 VÅRD AV EXTREMELY FÖR EARLYT WHO ARE BORN children SOCIALSTYRELSEN starting pharmacological treatment. A grade IV haemorrhage (larger haemorrhage) is judged to be a contraindication for pharmacological treatment. An impaired neurosensory capacity has been reported among children who have had an operation for PDA [102, 103]. However, available data is not sufficient to determine whether the link is due to the fact that the group who had operations were particularly ill and vulnerable, or due to the fact that there are risk factors that are specifically associated with the surgical intervention. Paralysis of the vocal cords (caused by damage to recurrent nerve) [104] and postoperative blood pressure drop [105] have also been shown to be common complications, and ductus surgery therefore ought to be carried out on a restrictive basis on extremely premature infants. CARE OF CHILDREN WHO ARE BORN EXTREMELY PREMATURELY THE NATIONAL BOARD OF HEALTH AND WELFARE 5 The immature brain The immature brains of extremely premature infants have a greater risk of being affected by damage and deviating development. During the neonatal care period, several factors can affect and disrupt the brain’s growth because it is in a dynamic development phase. This means that the children have a greater risk of being affected by neurological and cognitive function impairments as well as by neuropsychiatric condition such as ADHD and autism. These conditions are associated with complications that arise during the pregnancy and the neonatal period [106-108]. It has been shown that improved neonatal care reduces the brain injuries [3] and it is therefore extremely important for the initial care of these children to take place at hospitals that have substantial experience of and competence in neonatal specialist care. The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare’s assessment • • • • The care is of substantial significance to the risk of developing brain haemorrhages and damage in the brain’s white matter. It is therefore extremely important for the care to take place at units that have substantial experience of extremely premature infants. The brain ought to be continuously assessed to diagnose injuries and deviations as well as to inform the parents of the child’s condition and prognosis. The assessment ought to take place with the help of o clinical examinations; valid examination methods to detect brain injury, such as ultrasound, electroencephalography and magnetic resonance tomography. The businesses ought to draw up procedures to reduce risk factors that are linked to the development of brain injuries. Neurological and cognitive follow-ups ought to take place until school age in accordance with the national follow-up programme. The assessment is based on systematic charting and consensus between the chairpersons of the expert groups. Brain injuries The immature brains of extremely premature infants develop milder injuries such as haemorrhages and matter loss. The brain injuries which are diagnosed in the neonatal period in the first instance are known as intraventricular haemorrhages (IVH), which arise in an area from which nerve cells migrate [109-111]. In 90 per cent of the cases, IVH occur during the first week and usually already during the three first day of life. The size of the haemorrhage affects the prognosis where milder haemorrhages (IVH grades I-II) often do not lead to a great risk of a later impact, while larger haemorrhages 6 VÅRD AV EXTREMELY FÖR EARLYT WHO ARE BORN children SOCIALSTYRELSEN (IVH grades III-IV) involve a high risk of development of subsequent function impairments. Approx. 10-15 per cent of the extremely premature infants are also affected by haemorrhages in the cerebellum. The haemorrhages increase the risk of subsequent cognitive and motor function impairment. The risk of injuries in the brain’s white matter is also higher for these children. Cystic periventricular leukomalacia (cPVL) leads to a loss of matter in the brain which is linked to the development of motor and perceptual (the ability to perceive) function impairments. More diffuse white matter injury is also relatively common. Improved neonatal care, which is adapted to the very smallest children, has led to a fall in the occurrence of IVH grades III-IV and cPVL (and thereby also the risk of cerebral palsy), but 15-20 per cent of the extremely premature children [3] are still affected. Methods of detecting brain injuries Neurological assessment can be difficult to do on extremely premature infants. The child’s neurological function (such as muscle tone, activity, spasms, sleep and alertness) ought to be clinically assessed. Ultrasound examinations of the brain can give direct information on morphological injury. Both IVH and PVL can be detected, while substantial experience of haemorrhages in the cerebellum is required for them to be visible [109, 111, 112]. Ultrasound examinations ought to be performed on all of these children as a matter of routine within the first 3 days, after 3-7 days and after 14-21 days when the child has reached the estimated full term as well as in addition to that where necessary Where there is an increasing accumulation of cerebrospinal fluid (post-haemorrhagic ventricular dilation, PHVD) and the development of hydrocephalus (water on the brain), more frequent ultrasounds ought to take place and early contact be established with a neurosurgeon. The circumference of the child’s head ought to be routinely measured each week or more often if necessary. More diffuse white matter injury can be diagnosed using with magnetic resonance tomography (MR). After just one day, the brain activity registered with EEG (electroencephalography) or amplitude-integrated EEG (aEEG, a modified EEG), has been shown to predict a later prognosis. It shows the importance of the early brain injury’s role in the child’s future prognosis. EEG and aEEG examinations have also shown that subclinical (not fully developed) epileptic attacks are relatively common, primarily in children with IVH [109, 111, 112]. An ultrasound or MR of the brain ought to take place at full term or in the weeks before this. The injuries that can be seen at this time are often predictors of later problems but unfortunately, a normal examination does not always predict normal development. The examinations show that extremely premature infants, irrespective of whether or not there is a brain injury, have a lower brain volume when they have reached the full estimated term compared with full-term children. However, the scientific support for whether ultrasound [113, 114] or MR [115] gives the most suitable predictive information is not unequivocal. CARE OF CHILDREN WHO ARE BORN EXTREMELY PREMATURELY THE NATIONAL BOARD OF HEALTH AND WELFARE 7 Prevent brain injuries - risk factors There are no specific interventions to treat brain injuries that have arisen without focus being primarily on running the care in such a way that the children’s exposure to risk factors that are linked to brain injuries is minimised as far as possible. These risk factors include: • • • • • • • • • • • • • • inadequate and immature control of cerebral blood flow instable circulation unsuitable blood gas levels lung immaturity chronic lung disease interrupted breathing (apnoea) inadequate nutrition pain and stress surgical intervention persistent ductus arteriosus (PDA) transportation high bilirubin levels infection inflammation. Some of the injuries that arise can be related to the children’s relatively low and immature cerebral blood flow regulation. The child’s blood gas levels ought to be monitored continuously because high carbon dioxide levels lead to a greater risk of IVH while low levels increase the risk of cPVL and cerebral palsy [35]. Simple care measures such as changing nappies and adjusting the position of the tube can also affect the blood circulation and oxygenation of the brain. Lung immaturity and chronic lung disease are well-known risk factors for brain injury [116]. One of the most important results of giving mothers antenatal steroids so that the foetus’ lung function matures is that this also leads to a reduction in the risk of IVH. Both acute and more chronic nutrition problems are common in very premature children, and this increases the risk of injuries in and inadequate development of the brain. Hypoglycaemia is associated with impaired development, but moderate hyperglycaemia during the first day of life also involves a risk factor for white matter injury and death among these children [117]. A high sodium intake as well as the administration of hyperosmolar solutions have been shown to be linked with the development of IVH and ought therefore to be avoided [118]. Frequent pain and stress are linked to reduced brain growth and a change in cerebral organisation and can lead to both acute, physiological effects and permanent changes in the response to pain and the central nervous function [119, 120]. Painful measures should always be minimised. Surgical intervention and transportation also increase the risk of brain haemorrhages. High bilirubin levels can lead to brain injuries caused by kernicterus, although this is uncommon in Sweden. On the other hand, milder bilirubin encephalopathy (reversible brain damage) is more common and can, for example, express itself in terms of pronounced tiredness. The majority of extremely premature infants need light treatment to lower their bilirubin level, but it can be difficult to detect symptoms and see the characteristic yellow coloration of the skin in these children. 8 VÅRD AV EXTREMELY FÖR EARLYT WHO ARE BORN children SOCIALSTYRELSEN Infections Preventing infections is a key factor in all forms of care. It is particularly clear in the care of extremely premature infants because their defence against infections is underdeveloped. At the same time, the care of these children, like all intensive care, leads to considerable risks of infection, among other things through many invasive measures and the use of advanced technical equipment. The Healthcare and Medical Treatment Act (1982:763) requires care to maintain a good standard of hygiene and the hygiene requirement is also regulated in The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare’s provisions and general advice (SOSFS 2007:19) on basic hygiene within healthcare and medical treatment, etc. There is also a requirement regarding measures to prevent infection in The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare’s provisions and general advice (SOSFS 2011:9) on management systems for systematic quality work. Prevent the spreading of infections The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare’s assessment • • • Units that care for extremely premature infants ought to have safety procedures which aim to prevent the occurrence of infections and spreading of infection. Extremely premature infants are often cared for at several hospitals and the care providers therefore ought to coordinate their hygienic procedures and the information concerning the risks of infection. In the systematic quality work, it is necessary to register care-related infections with follow-up and feedback. The assessment is based on hygiene requirements in the Healthcare and Medical Treatment Act (1982:763) and The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare’s provisions (SOSFS 2007:19 and SOSFS 2011:9) as well as on knowledge bases and reports from The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare and recommendations from the Medical Products Agency. Care-related infections are a documented problem at several neonatal units. Shortcomings in care hygiene have been noticed particularly in connection with the spreading of multiresistant bacteria, including ESBL-forming gram-negative bowel bacteria [121]. Crowded care spaces can increase the risk of care-related infections, which is described in SOSFS (2011:9). The extremely premature infants ought to be cared for in appropriate premises, which is not always the case today. The technical medical equipment requires more room and the fact that parents assist with the care means that each child needs considerably more space than before. The parents’ assistance is an important and key part of Swedish neonatal care and the businesses must therefore have procedures to inform the parents of the hygiene rules that apply. Basic hygiene rules must always CARE OF CHILDREN WHO ARE BORN EXTREMELY PREMATURELY THE NATIONAL BOARD OF HEALTH AND WELFARE 9 be applied to point-of-care work to prevent the spreading of patient and hospital flora. Since an extremely premature child is cared for at several different hospitals, coordination is needed between different care providers’ hygiene procedures. The use of antibiotics within neonatal intensive care is extensive. Antibiotic treatment often starts before the suspicion of an infection is confirmed because serious infections are relatively common and the symptoms are usually difficult to interpret when the course of events starts. The Medical Products Agency has produced recommendations for the treatment of serious neonatal infections [122] where you can read things like: “antibiotic treatment must be designed optimally with regard to the choice of antibiotic and the period of treatment to minimise the risks of treatment failure and resistance development”. Read more Information from the Medical Products Agency: • • Recommendations for the treatment of neonatal sepsis (Neonatal sepsis - ny behandlingsrekommendation (English: Neonatal sepsis - new treatment recommendation). Information from the Medical Products Agency 2013; 24(3):1525). The importance of hygiene procedures to prevent infections and the reasonable use of antibiotics (Riesenfeld-Örn, I, Aspevall, O. Vårdrelaterade infektioner, antibiotika och antibiotikaresistens (English: Care-related infections, antibiotics and antibiotic resistance). Information from the Medical Products Agency. 2013; 24(3):77). Information from The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare: • • 10 Inventory of problems and proposed measures for the spreading of infection within Swedish neonatal healthcare (Smittspridning inom svensk neonatalsjukvård probleminventering och åtgärdsförslag. The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare; 2011). A knowledge basis for the prevention of care-related infections (Att förebygga vårdrelaterade infektioner - Ett kunskapsunderlag. The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare; 2006). VÅRD AV EXTREMELY FÖR EARLYT WHO ARE BORN children SOCIALSTYRELSEN Nutrition - a precondition for growth and development Extremely premature infants often have an inadequate nutritional intake and demonstrate inhibited postnatal growth, which can be explained partly by undernutrition [123]. The children are unique when it comes to the need for nutrition and the nutrition during the first months of life plays a major role. In order to achieve normal growth and development, premature children ought to grow in accordance with the curve for normal foetal growth [124]. Foetal growth is much faster than that of the newborn, which leads to extremely premature infants needing more nutrition than full-term children. A child who is born after 24 full weeks of pregnancy have passed and weighs around 700 g, for example, is expected to increase its body weight by five times over the next 3 ½ months of care in neonatal unit. The nutrition must not only result in normal growth, i.e. weight, height, head circumference and body composition, but also in normal growth and maturation of all organ systems. Nutritional intake and monitoring of the growth The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare’s assessment • • The child’s nutritional intake needs to be safeguarded through individual nutritional calculation and continuously assessed in order to detect a nutritional shortcomings, excess nutrition or disturbances to the metabolism. o Recommended nutritional intake is shown in Appendix 1. o the child’s weight ought not to drop by more than 5-10 per cent in the first three days of life. The child’s nutrition and growth ought to be followed up after discharge. The assessment is based on consensus between the chairpersons of the expert groups. Extremely premature infants are at great risk of being undernourished during the care period at a neonatal unit [123, 125]. In the short term, this is linked with poor growth and in the long term with severe complications such as vision impairment, development disorder and cardiovascular disease [6]. It is not possible to give any general recommendations for nutritional intake because the need for nutrition varies and depends on the week of pregnancy in which the child is born, postnatal age, state of health, weight, growth pattern, nutritional status and the share of enteral (through the gastrointestinal tract) or parenteral (intravenous) nutrition. The nutritional intake ought therefore to be calculated on an individual basis at regular intervals. Recommended nutritional intake is presented in Appendix 1 [126-128]. The extremely premature infant will rapidly form substantial accumulated nutritional shortcomings if the prescribed nutritional intake is lower than that which is CARE OF CHILDREN WHO ARE BORN EXTREMELY PREMATURELY THE NATIONAL BOARD OF HEALTH AND WELFARE 11 recommended, and it is therefore necessary to think about the nutritional intake on a daily basis [129]. The nutritional intake is at its lowest during the first four weeks of life [123] and the weight loss at its fastest during the first week, but the children often demonstrate a progressive growth inhibition during the first four weeks where weight, height and head circumference are concerned. During this period, the children are usually given a combination of parenteral and enteral nutrition. Other undernutrition risk periods are at the time of surgery [101], when the child has been discharged from the neonatal unit and when the child changes from tube nutrition to nursing because that is when it becomes more difficult to estimate the nutritional intake. Nursing is important, however, and breast milk is the best food for the children. After going home, the follow-up and advice to the parents vary, and the rate of growth can fall rapidly if the child is not mature enough to regulate his own intake or has difficulties eating. In order to optimise growth and development, it is important for the children to be followed up at outpatient appointments within neonatal outpatient care or in cooperation with primary care or specialist clinics [130]. There are no evaluations of the effect of the upper limits for a safe intake of many nutrients. An unnecessarily high intake of iron (at the time of blood transfusions for example) which cannot be excreted from the body has been linked to impaired growth and an increase in the risk of infections and retinopathy of prematurity, among other things [131, 132]. Growth measurements Weight is measured on a daily basis if possible, while height and head circumference can be measured once a week. Any growth deviations are clarified by plotting the growth against the normal growth curve for healthy foetuses. During the first three days of life there will be an initial weight loss which ought to be no more than 5-10 per cent, but after that, the child is expected to grow in parallel with the intrauterine growth curve. Children who have full enteral nutrition and enjoy good and stable growth can be weighed every other day [133]. Blood tests During the first two weeks of life, the level of glucose and electrolytes as well as the acid base status in the blood need to be followed up. This applies in particular if the child is clinically unstable. Triglycerides, urea and creatinine also need to be followed up. The indication for a blood test must be weighed against the negative effects such as pain and anaemia. 12 VÅRD AV EXTREMELY FÖR EARLYT WHO ARE BORN children SOCIALSTYRELSEN Parenteral nutrition The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare’s assessment o Parenteral nutrition solution ought to be given as soon as possible (within a few hours) after the birth, along with an early start to an enteral supply of breast milk. The assessment is based on systematic charting. Parenteral nutrition is an invasive treatment which involves a high risk of complications (particularly care-related infections) and there should therefore be substantial experience, well-functioning procedures and careful monitoring of the treatment. The child’s rapid growth requires a very high supply of energy and nutrients already during the first hours of life. This can take place using a concentrated parenteral nutrition solution through a central vein along with a rapid increase in the enteral supply of breast milk [134, 135]. Fluid and salt balance The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare’s assessment o The fluid and salt balance ought to be carefully controlled, particularly during the first week of life. The assessment is based on consensus between the chairpersons of the expert groups. An adequate fluid and salt balance is necessary to avoid disorders such as dehydration, overhydration, electrolyte disorders and metabolic acidosis, which in turn can lead to a rise in mortality and morbidity [45]. In extremely premature infants, the body’s total fluid content corresponds to 90 per cent of the birth weight The children’s kidney function is immature, limited and borders on kidney failure levels. These special circumstances mean that there is a fine balance between fluid and salt; disorders are common and small imbalances can have major consequences, primarily during the first few weeks of life. An early supply of phosphate, calcium and magnesium ought to be given if possible. Low quantities of sodium and potassium can be tolerated in connection with satisfactory nutrition. The fluid and sodium chloride intake ought to be limited during the first three days of life (Appendix 1). Fluid sometimes also needs to be restricted later on for clinical reasons, and then it is particularly important to provide adequate nutrition by using sufficiently concentrated nutritional products. CARE OF CHILDREN WHO ARE BORN EXTREMELY PREMATURELY THE NATIONAL BOARD OF HEALTH AND WELFARE 13 Enteral nutrition The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare’s assessment • The businesses ought to have written procedures for the handling of breast milk and bank milk, as well as access to a breast pump. The giving of breast milk should o be the first choice for enteral nutrition o be enriched on an individual basis to optimise the nutrition o be encouraged in the form of nursing following discharge. The assessment is based on systematic charting. The gastrointestinal tract becomes functionally mature more quickly if the enteral supply is started early on, which also reduces the need for parenteral nutrition and thereby the risk of invasive infections [136, 137]. The enteral nutrition is escalated with the aim of achieving full enteral nutrition within 14 days of the birth. If possible, the child ought to be given drops of its mother’s colostrum or breast milk by mouth because it gives protection against infection and positively stimulates the sense of taste [138]. Breast milk is superior as nutrition for extremely premature infants, partly because it reduces the risk of developing necrotising enterocolitis (inflammation of the bowel) [139]. If the mother does not have her own milk, bank milk (donor milk) is the best alternative (following the parents’ consent) [139]. Only in the third instance can it be relevant to use infant formulas for children who are born prematurely. To promote nursing, it is good if the first milk is obtained within six hours of the birth if possible, as well as continuing with milkings at least six times a day [140]. Mother and child skin-toskin contact supports the production of milk and the child’s nursing behaviour [141]. The parents ought to be given information, preferably before the birth, on the importance of colostrum and breast milk as well as the importance of early milking. Rearing with non-fortified breast milk, primarily bank milk, involves a major risk of protein shortfall as well as lack of energy and various minerals. In order for the nutritional intake via breast milk to be sufficient, the milk needs to be analysed and almost always fortified [142, 143]. The fortification ought to be individualised because it reduces the risk of under and overnutrition. The easiest way of creating a suitable fortification is to regularly analyse the breast milk content for protein, fat and carbohydrates [144]. 14 VÅRD AV EXTREMELY FÖR EARLYT WHO ARE BORN children SOCIALSTYRELSEN Retinopathy of prematurity Extremely premature infants are at risk of being affected by the eye disease called retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) which is due to a change in the blood vessel development in the eye. The vascular disease can cure itself and the visual impairment can be prevented through timely laser treatment or cryotherapy. Approx. 30 per cent of extremely premature infants develop serious ROP which requires acute treatment to prevent the retina from becoming loose and vision being lost (less than 1 per cent of the children are blind) [5]. The earlier the child is born, the greater the risk of being affected by ROP, which is due to the less-developed blood vessels in their retina. The supply of oxygen to these children ought to remain at a suitable and stable level because the children are sensitive to both high (hyperoxia) and low oxygen pressure in the blood. Hyperoxia and major fluctuations in the oxygenation early on in life are associated with a greater risk of ROP. The risk of ROP is reduced with lower exposure to oxygen, but too severe a restriction is associated with an increase in mortality [37]. A more detailed description of oxygen treatment is given in the guideline’s chapter on lung diseases and breathing support. Undernutrition and protein shortfall have been linked to an increase in the risk of ROP, and there is some scientific support for the fact that a high intake of iron also increases the risk [131, 132]. Diagnostics and treatment The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare’s assessment • • There ought to be procedures for regular ophthalmological examinations to diagnose retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) early on. Advanced ROP (stages 3-4) requires acute eye surgery (usually laser) and this is done under general anaesthesia. The assessment is based on the Swedish Ophthalmological Society’s guidelines and consensus between the chairpersons of the expert groups. Screening for ROP ought to include all extremely premature infants and be carried out in accordance with Sweden’s Ophthalmological Society’s guidelines [145]. The examination result ought to be registered in the national quality register (SNQ with its SWEDROP register) [146]. An eye examination for the assessment of ROP is a painful procedure and the pain is prevented through eye drops along with non-pharmacological support [147, 148]. CARE OF CHILDREN WHO ARE BORN EXTREMELY PREMATURELY THE NATIONAL BOARD OF HEALTH AND WELFARE 15 Read more • 16 “En kunskapsöversikt om prematuritetsretinopati” (English: A knowledge overview of retinopathy of prematurity) (Holmström, G. Retinopathy of prematurity, state of the art - document 2012. [quoted 201407-01]; Available from: http://swedeye.org/wp-content/uploads/ROP-2012.pdf). VÅRD AV EXTREMELY FÖR EARLYT WHO ARE BORN children SOCIALSTYRELSEN Treatment of pain Children who are born prematurely and who are cared for at neonatal intensive care units are often exposed to pain due to their immaturity, different states of health, complications and care procedures. The pain can have negative consequences in both the short and the long term because the immature child is in a sensitive period of strong growth and differentiation of the central nervous system. Therefore, the number of painful interventions ought to be minimised and painful conditions be treated. Pain ought in the first instance to be dealt with using non-pharmacological treatment, but there are circumstances when the pharmacological treatment of pain is necessary. The majority of the medicines used are not fully tested and documented (effect, safety and dose) for extremely premature infants, so the treatment is based largely on tried and tested experience rather than scientific support. The fact that medicines lack an approved indication need not mean that the knowledge is inadequate since there is often good clinical experience of them. Extremely premature infants ought to be ensured a pain-free existence as far as possible, despite the fact that they have other physiological conditions to react to and express their pain compared with full-term children. The risks of treatment with medicines (toxic effect and side effects) must be weighed against the pain the child perceives without pharmaceutical painkillers and also against the injuries that can arise due to the pain. This is a difficult but very important fine line to walk and modern neonatal treatment of pain is therefore based on a balanced, multimodal strategy [149]. This strategy involves regular pain assessment, individualist behaviour support (nonpharmacological) treatment and, if necessary, pharmacological treatment as well. Pain assessment The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare’s assessment • For pain diagnostics, pain ought to be assessed with the help of valid instruments (adapted according to age, level of maturity and type of pain) as far as possible. The assessment is based on Swedish guidelines from the Swedish Child Pain Society and guidelines drawn up by an international consensus group. Both international and national guidelines and procedures recommend that all units which care for newborn children must have procedures that include a structured pain assessment model [150, 151]. It is fundamental for an objective pain assessment to be able to provide adequate and safe treatment of pain for these children. There is no golden rule for objective pain assessment, but different observational scales are usually used. However, it is urgent to CARE OF CHILDREN WHO ARE BORN EXTREMELY PREMATURELY THE NATIONAL BOARD OF HEALTH AND WELFARE 17 choose valid instruments that have been designed for the child’s level of maturity and type of pain, such as acute procedural pain or continuous pain and stress (for example through respirator treatment or postoperative care). Appendix 2 shows the pain assessment instruments that are often used and which are recommended in today’s neonatal care. Non-pharmacological treatment of pain The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare’s assessment • • The number of painful interventions ought to be minimised. Extremely premature infants ought always to be given non-pharmacological, individualised care to reduce the perception of pain and stress. This may include o thinking through and optimising the care environment, calm for example; o the participation of the parents; o the use of skin-to-skin care and supportive cohesion; o ensuring that the child is replete, dry and warm before procedures; o ensuring that the child is lying comfortably; o ensuring that the child is given the option of something non-nutritive on which to suck. The assessment is based on Swedish guidelines from the Swedish Child Pain Society and guidelines drawn up by an international consensus group. Children who are cared for at neonatal units undergo a large number of measures that are painful to a greater or lesser extent on a daily basis. The very smallest and youngest patients are the most sensitive and can also experience nappy changing or turning over as painful. The basic principle is that the number of painful interventions should always be minimised. There are several non-pharmacological strategies that can reduce the child’s pain reaction and have a calming effect. The care environment ought to be optimised, including by minimising disruptive visual and audible impressions. An example of this is subdued direct lighting, particularly to start with when the child is especially sensitive. The child ought to be replete, dry and warm before painful procedures. The child ought also to be assisted with something non-nutritive on which to suck, which means that the child sucks on something such as a dummy, a hand or a finger (its own or that of the parent) [152]. If possible, the parents ought always to be engaged in the treatment of pain, partly so that they can report the child’s pain and partly because they will be able to offer supportive measures such as skin-to-skin care (HMH) or supportive cohesion [153]. 18 VÅRD AV EXTREMELY FÖR EARLYT WHO ARE BORN children SOCIALSTYRELSEN Pharmacological treatment of pain The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare’s assessment • • Each unit ought to have well designed pharmacological pain treatment procedures which are also suitable for acute situations. The procedures ought to cover pain in situations such as: o procedural pain, including intubation o postnatal and postoperative pain o treatment of continuous pain and stress during respirator treatment. Pharmacological treatment ought to be administered in good time before painful procedures and ought always to be supplemented with non-pharmacological support. The assessment is based on Swedish guidelines from Swedish Child Pain Society and guidelines drawn up by an international consensus group. More painful intervention, such as pinpricks, the insertion of a central venous catheter or of drainage, intubation, operation and respirator treatment, usually requires pharmacological treatment of pain in addition to the non-pharmacological treatment which always constitutes the basis of the pain treatment strategy. The pharmacological treatment can include both analgesics (painkillers) and sedatives (calming or soporific medicines) which have been selected on the basis of how painful the condition or measure actually is. There is clinical experience of which preparations ought to be used for extremely premature infants, but the scientific support is limited. Medicines ought to be prescribed using a conscious strategy. Each unit ought to have procedures with proposed treatments that are well-established, that are safe to use even in an emergency situation, and that are carefully documented and followed up. For mild to moderate pain, a painkilling effect can often be achieved by administering sweet solutions (concentrated glucose or sucrose) by mouth to newborn children [154]. The positive effects have also been seen in extremely premature infants, even though the scientific support is limited [155]. Premedication ought always in principle to be given prior to intubation as well as directly after the birth or in other acute situations when there is no intravenous access. Postoperative pain and painful conditions such as necrotising enterocolitis should always be treated pharmacologically. With respirator treatment, non-pharmacological support may be sufficient if there is no other reason for the pain such as a painful condition or during postoperative care. However, treatment with medicines may be relevant as age and treatment time increase because the perceived stress of respirator treatment can then increase [156]. Medicines ought to be administered in good time before a painful procedure. Where there are combinations of medicines, they should be given sequentially based on time of onset, properties and effect. Preparations with a rapid time of onset and short duration of effect are considered to be ideal for a short-term and acute procedure such as intubation [157]. For CARE OF CHILDREN WHO ARE BORN EXTREMELY PREMATURELY THE NATIONAL BOARD OF HEALTH AND WELFARE 19 sedation, the child ought to have stable blood pressure because this always leads to some risk of a drop in blood pressure. Sedation with benzodiazepines is not advised for extremely premature infants [158]. Medicinal substances are usually absorbed and eliminated more slowly in newborn children, which is much more the case in extremely premature infants. If several medicines are used simultaneously, an effective combination of as few medicines as possible needs to be found because combinations can be risky. However, in some cases, primarily when using opioids, it can be advantageous to use combinations of several different medicines where the effects of the different preparations fortify one another, which means that the strength of the doses can be reduced and thereby also the side effects of each individual medicine. This applies to postoperative care, for example, when treatment with Paracetamol, opioids and Clonidine may be appropriate. The time to discontinue certain analgesics such as opioids ought to be individualised. The time depends on the dose that the child has received as well as the length of time for which the treatment has lasted. First of all there ought to be a gradual reduction in the size of the dose followed by a reduction in the number of doses. Abstinence symptoms may be difficult to interpret in extremely premature infants but if symptoms do arise, the original dose should be used and the dose not continue to be reduced until the child is abstinencefree. Read more • • 20 Businesses that must produce procedures can obtain support from guidelines from a workgroup within the Swedish Child Pain Society. Nationella riktlinjer för prevention och behandling av smärta i nyföddhetsperioden (English: National guidelines for the prevention and treatment of pain in the neonatal period), revised 2013 [quoted 04/07/2014]; Available from: http://www.svenskbarnsmartforening.se/svenskbarnsmartforening/docum ent/Nationalriktlinjer-2013.pdf). There is information from the Medical Products Agency on pharmacological preparations for full-term children which may also give some guidance for the care of extremely premature infants (Behandling av barn i samband med smärtsamma procedurer i hälso- och sjukvård - kunskapsdokument (English: Treatment of children in connection with painful procedures in healthcare and medical treatment – knowledge document). Information from the Medical Products Agency 2014; 25(3):922). VÅRD AV EXTREMELY FÖR EARLYT WHO ARE BORN children SOCIALSTYRELSEN Nursing The care of extremely premature infants concentrates on saving lives but also on promoting the child’s long-term health and development. Right from the birth and onwards throughout the care period, the nursing ought to be adapted to the child’s relevant level of development so that stimuli are as beneficial as possible and negative effects of stress and pain as small as possible. High quality nursing ought to be individualised, support development and be centered around the family. Care centered around the patient and the family The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare’s assessment • The care of extremely premature infants ought to be organised so that it is centered around the patient and the family. This means that the care should be: o o o o o individualised support development offer family care offer integrated care actively involve and inform the parents. The assessment is based on systematic charting and consensus between the chairpersons of the expert groups. Care centered around the patient and the family is an approach whereby the care is not limited to just being disease-orientated but is extended to cover other needs of the child, parents and any siblings. The UN’s Children’s Convention forms the basis for the child’s rights as an individual and as part of the family [159, 160]. There are also specific policy documents for family-centered [161, 162] and neonatal nursing [163, 164]. Care centered around the patient and the family involves the following: • • • • • Family care is offered, which means that parents and children are not separated The care ought thereby to offer accommodation for the parents to stay at the newborn’s unit. Mothers with their own medical needs ought as far as possible to be integrated into the care with the child at the newborn unit. The family’s individual needs being respected as far as possible. The parents’ sensitive needs being noted. The parents ought to be offered psychosocial support and support in the bonding and the anaclytic process, which also includes nursing support (see also the chapter on nutrition). The parents being encouraged to take responsibility themselves for the child’s nursing. The development benefits from parents being present for a lot of the time and from early interventions focusing on the interaction between the child and the parents. CARE OF CHILDREN WHO ARE BORN EXTREMELY PREMATURELY THE NATIONAL BOARD OF HEALTH AND WELFARE 21 • • All information is shared with the parents if there is no obstacle in doing so in the Public Access to Information and Secrecy Act or Chap. 6, Sections 3 and 4 of the Parental Code. Facilitating the cooperation between parents and personnel. Care centered around the patient and the family is key to successful bonding and the anaclytic process between children and parents. The anaclytic process is crucial to the development of the brain and the child’s ability to handle stress, which in turn affects the child’s general development and its future health. A good anaclytic process is also important so that the parents can feel secure in their parental role [165]. However, the short pregnancy period can make this difficult because the parents may have a natural crisis reaction and because the anaclytic process has to be developed during the neonatal care period. Extremely premature infants also give weak signals and often have behaviour that is different and more difficult to interpret compared with full-term children [166, 167]. It is therefore essential that the units have competence to read the premature child’s signals. Development-supporting nursing Development-supporting care is based partly on the medical treatment but also on sociology and behavioural science The basis is the competence to understand the child’s behaviour, to support the child’s autoregulation (of the nervous system, alertness and interaction with the surroundings, for example) as well as benefitting the parents’ and the care personnel’s interaction with the child. Individually-adapted, development-supporting care ought to be offered since the care gives positive short-term effects and increases the child’s well-being during the neonatal care period, even though the long-term effects have weaker scientific support. Adapting the care to the individual and striving for calm surroundings increases the possibilities of undisturbed sleep and a more beneficial development for the child. The lower the lower level of maturity, the clearer the positive effects on the child’s development. There are different intervention programmes that can be used within the care of extremely premature infants. NIDCAP (newborn individualised developmental care and assessment programme) is a programme that can be carried out throughout the care period, starting directly after the birth, which is significant from a neurobiological development perspective [168]. A key moment in NIDCAP is the individual assessment of the child’s responsiveness to and capacity to handle stimuli. Other elements include the positioning of the child, adaptation of the surrounding environment as well as conduct at the time of specific care measures. There is some scientific support to show that NIDCAP has positive short-term effects on the more serious forms of bronchopulmonary dysplasia as well as reducing the incidence of necrotising enterocolitis and improving the situation for the families. The studies also showed positive long-term effects on the children’s behaviour and motor skills [163, 169]. Other studies have shown that NIDCAP has a positive impact on the maturity of the brain and on the cognitive development [170, 171] as well as leading to shorter care periods [172]. Many neonatal units use modified NIDCAP care which works towards the same target with the same means but do not fully include all observational elements. The methods MITP (mother infant transaction programme) and IBAIP (infant behavioural assessment and intervention programme) are based on the same theoretical basis as NIDCAP. The methods are primarily intended to 22 VÅRD AV EXTREMELY FÖR EARLYT WHO ARE BORN children SOCIALSTYRELSEN be used following discharge and aim to strengthen the communication between children and parents. MITP has been shown to reduce the level of stress in the parents during the child’s first year and a beneficial effect was seen on the child’s cognitive development at five years of age [173, 174]. IBAIP has also been shown to improve the motor development for children with a birth weight of less than 1 500 g and, at the five-year follow-up, showed better cognition (performance IQ) as well as the ability to coordinate visual impression and movement patterns (visual-motor integration) [175, 176]. One method that is often used and which ought to be offered 24 hours a day is skinto-skin care (HMH, also called kangaroo mother care, KMC). The method is based on the fact that the child has direct skin contact with a parent or a close family member. The scientific support for the positive effects of the method is found mainly in the low income countries [177-179]. Studies have shown that HMH contributed to lower mortality, fewer serious infections and other medical conditions, better temperature regulation as well as shortened care periods. The method has also been shown to act as a pain alleviator [152, 180, 181] and to have a positive effect on the child’s growth, the mothers’ satisfaction and bonding with the child following discharge [182], the mother’s milk production and the child’s nursing behaviour [141]. In turn, a longer nursing period has a positive effect on the child’s cognitive development [182]. CARE OF CHILDREN WHO ARE BORN EXTREMELY PREMATURELY THE NATIONAL BOARD OF HEALTH AND WELFARE 23 The dilemma surrounding life support treatment • Healthcare and medical treatment must offer all children good healthcare and medical treatment on the same terms as the general population. All living premature children must be given a chance of survival, irrespective of age, as long as this is compatible with science and tried and tested experience. The care of extremely premature infants is complicated. It includes forming opinions concerning suitability for life beyond the foetal stage and decisions to refrain from or turn off life support treatment. The national study EXPRESS (extremely preterm infants in Sweden study) showed that 40 per cent of the children who had survived at least 24 hours but who later died during ongoing neonatal intensive care died following a decision to stop life support measures. EXPRESS showed that there were major differences in the care between children who are born in the 22nd and 23rd week of pregnancy: neonatal care (48 compared with 83 per cent), intubation at the time of the birth (59 compared with 81 per cent) as well as the survival rate upon birth and admission to the neonatal intensive care department (38 compared with 81 per cent) [4]. The handling must not be based solely on the basis of the duration of the pregnancy because the care must not discriminate against a patient on the basis of age, which is shown by the Healthcare and Medical Treatment Act (1982:763) (HSL) and the Discrimination Act (2008:567). Such handling is also limited by the accuracy of the pregnancy dating and by individual variations in level of maturity and risk factors. Forming opinions It is impossible to give detailed guidance that can be applied in all different situations. The care personnel must use their professional knowledge to make the medical assessments (Chap. 6 of the Patient Safety Act [2010:659] (PSL) as well as Chapters 2 and 3 of The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare’s provisions and general advice [SOSFS 2011:7] on life support treatment). One condition for the care personnel’s work is that the care provider must ensure that there is a management system that is used to systematically and continuously develop and secure the quality of the activity (Chap. 3, Section 1 of The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare’s provisions and general advice [SOSFS 2011:9] on management systems for systematic quality work). Situations that are not clear and are difficult to assess will always arise, and it is sometimes necessary to consider whether it is compatible with science and tried and tested experience to provide life support treatment if there are no further cures that can be offered (the principles are based on 6 Chap. of HSL, PSL, SOSFS [2011:7] and The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare’s handbook, Om att ge eller inte ge livsuppehållande behandling - Handbok för vårdgivare, verksamhetschefer och personal (English: To give or not give life support treatment - Handbook for care providers, operations managers and personnel) [183]). It is an obvious thing to avoid or stop those measures that are doing more harm than good. In some situations and following an individual assessment, 24 VÅRD AV EXTREMELY FÖR EARLYT WHO ARE BORN children SOCIALSTYRELSEN the doctor responsible may assess that life support treatment must not be started even if the child shows signs of life when born. • • • “Before forming an opinion not to introduce or continue life support treatment, the permanent care contact must consult at least one other registered professional. The permanent care contact should also consult other professionals who are taking part or have taken part in the patient’s care” (Chap. 3, Section 2 of SOSFS [2011:7]). “If no doctor has yet been appointed to be responsible for the planning for the patient, a responsible consultant or second on call must apply the regulations...” (Chap. 3, Section 4 of SOSFS [2011:7]). The patient must be offered palliative care with as good a quality of life and symptom-alleviating powers as possible [183]. Feedback consultations and informative talks with the parents or close relatives must be given (HSL and SOSFS [2011:7]). The participation of the parents It is vital that the parents are informed of the child’s condition and chances of survival as early as possible. According to Swedish Law, the guardian is the legal representative of patients under the age of 18 and must decide on the child’s personal affairs. The parents’1 wishes regarding the child’s care must be respected as long as this can be seen to benefit the child’s interests and right to a life of value as well as well as being compatible with expert and scrupulous care that satisfies the requirements regarding science and tried and tested experience (Chap. 6 of PSL, Chap. 6, Section 11 of the Parental Code [ 1949:381] and The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare’s handbook on life support treatment [ 183]). A doctor cannot be forced to carry out a measure that would not benefit the patient but it can sometimes be important to give parents or close relative time, provided that this does not lead to suffering for the child, to digest the bleak prognosis of the condition before treatment is stopped. If a parent does not want life support treatment to begin, it is important for the care contact to ensure that he or she comprehends the information, is able to realise and survey the consequences of not starting or continuing the treatment, has had sufficient time to consider matters and is firm in his or her opinion (Chap. 4, Section 1 of SOSFS 2011:7). Documentation One way of ensuring the child’s and the parents’ moral and legal rights, as well quality assuring the care, is to individualise the forming of opinions and to improve the documentation on decisions to refrain from or stop life support treatment for extremely premature infants. Good documentation, procedures and a clear allocation of responsibility makes it easier to examine different courses of events in the care, such as if a decision regarding life support treatment is subsequently questioned. Requirements regarding documentation are set in Chap. 3 of The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare’s provisions and general advice (SOSFS 2008:14) on handling information and keeping records in healthcare and medical treatment as well as in Chap. 3, Section 3 of SOSFS (2011:7) where it says: “The permanent care contact must document in the patient record 1 25 Translator’s note: it is assumed that this is what was intended rather than the typo in the Swedish. CARE OF CHILDREN WHO ARE BORN EXTREMELY PREMATURELY THE NATIONAL BOARD OF HEALTH AND WELFARE 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 26 his or her opinion on life support treatment, when and on which grounds he or she has made said opinion, when and which professional he or she has consulted, at which times consultation with the patient has taken place, if consultation with the patient has not been possible and, if so, the reason for this, when and in which manner the patient and close relative have received individuallyadapted information in accordance with Section 2 b of the Healthcare and Medical Treatment Act (1982:763), and which opinion on the life support treatment the patient or close relative expresses” CARE OF CHILDREN WHO ARE BORN EXTREMELY PREMATURELY THE NATIONAL BOARD OF HEALTH AND WELFARE Follow-up of the children The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare’s assessment • Businesses caring for extremely premature infants ought to follow up the children in the short and long term. The assessment is based on consensus between the chairpersons of the expert groups. The increase in survival rate among premature children and changes to treatment methods lead to greater knowledge of the long-term and often complex consequences of premature birth. To increase the knowledge and further improve the work, a structured follow-up system is required which includes several different professions and which follows the children up to school age. The Swedish Neonatal Society will facilitate an equivalent follow-up of neonatal infants at risk in Sweden and the Society is therefore in the process of producing national recommendations for such a structured follow-up [184]. The objective of such a follow-up is to identify and diagnose deviations in the individual child at an early stage and thereby provide conditions for early treatment and appropriate support for the child and its family. By collecting and compiling follow-up data, it is also possible to follow up the quality and scientifically assess the neonatal care and the treatment. Swedish follow-up data is also needed to be able to inform parents who have recently had very sick children of the future prognosis their child. The Swedish neonatal quality register (SNQ) is an important source of knowledge for this. CARE OF CHILDREN WHO ARE BORN EXTREMELY PREMATURELY THE NATIONAL BOARD OF HEALTH AND WELFARE 27 Project organisation Project management Lars Björklund lung diseases expert group chairperson and responsible for the taking into care section Dr. of Med. and consultant, Skåne University Healthcare Mats Eriksson nursing, treatment of pain and brain expert group chairperson, as well as scientific advice at The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare senior lecturer at Örebro University and specialist nurse at University Hospital Örebro Lena Hellström Westas scientific advice at The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare and expert group convenor Professor at Uppsala University and consultant at Akademiska sjukhuset Stellan Håkansson transportation expert group chairperson, senior lecturer and consultant, Norrland University Hospital Mikael Norman PDA expert group chairperson Professor at Karolinska Institutet, and operations manager and consultant at the Astrid Lindgren Children’s Hospital Staffan Polberger nutrition expert group chairperson senior lecturer and consultant, Skåne University Healthcare project manager (2014), The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare Eleonora Björkman Charlotte Fagerstedt Anette Richardson project manager (2013-2014), The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare unit manager, The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare Michael Soop project manager (2010-2011), The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare Andor Wagner project manager (2012), The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare Participants in the lung diseases expert group 28 Thomas Abrahamsson Veronica Berggren Dr. of Med. and consultant at the University Hospital in Linköping registered children’s nurse at the Astrid Lindgren Children’s Hospital Kajsa Bohlin Kristina Bry Dr. of Med., Karolinska Institutet, and consultant at the Astrid Lindgren Children’s Hospital Professor and consultant at Drottning Silvia’s Children’s Hospital Johanna Dalström Aijaz Farooqi paediatrician at Falu General Hospital Dr. of Med. and consultant, Norrland University Hospital CARE OF CHILDREN WHO ARE BORN EXTREMELY PREMATURELY THE NATIONAL BOARD OF HEALTH AND WELFARE Ola Hafström Dr. of Med., consultant and head of section at Skåne University Healthcare Baldvin Jönsson senior lecturer at Karolinska Institutet and consultant and head of section at the Astrid Lindgren Children’s Hospital Kenneth Sandberg senior lecturer and reg. doctor at Drottning Silvia’s Children’s hospital Richard Sindelar Dr. of med. and consultant at Akademiska barnsjukhuset Participants in the transportation expert group Uwe Ewald Anders Adj. Professor and consultant at Akademiska sjukhuset Fernlöf Barbara hospital engineer at Akademiska sjukhuset Graffman paediatrician and neonatologist at the University Hospital in Linköping Boubou Hallberg Dr. of Med. at Karolinska Institutet and consultant and head of section at the Astrid Lindgren Children’s Hospital Tova HannegårdHamrin specialist doctor in anaesthesia and intensive care, senior registrar at the Astrid Lindgren Children’s Hospital Elisabeth Hentz Dr. of Med. and consultant at Drottning Silvia’s Children’s hospital Sven Johansson Johan Robinson Bo Selander Johannes van de Berg consultant at Ryhov County Hospital consultant at Norra Älvsborg County Hospital consultant at the Central Hospital in Kristianstad Ulf Westgren senior lecturer at Lund University, and consultant at Helsingborg General Hospital nurse, deputy lecturer and transport manager at Norrland University Hospital Participants in the PDA expert group Anna-Karin Edstedt Bonamy Dr. of Med. and assistant consultant at Sachsska Children’s Hospital Ola Hafström see above Stellan Håkansson see above David Ley Professor and consultant at Skåne University Healthcare Per Winberg Dr. of Med. and consultant at the Astrid Lindgren Children’s Hospital CARE OF CHILDREN WHO ARE BORN EXTREMELY PREMATURELY THE NATIONAL BOARD OF HEALTH AND WELFARE 29 Participants in the immature brain, treatment of pain and nursing expert group Lena Hellström Westas see above Ann-Sofi Ingman specialist nurse and NIDCAP trainer at the Astrid Lindgren Children’s Hospital Elisabeth Dr. of Med. and consultant at Skåne University Healthcare Norman Mats Blennow Professor at Karolinska Institutet and consultant at the Astrid Lindgren Children’s Hospital Björn Westrup Dr. of Med. at Karolinska Institutet and consultant at the Astrid Lindgren Children’s Hospital Participants in the nutrition expert group 30 Magnus Domellöf lecturer and unit manager, Umeå University Ann Dsilna Lindh Dr. of Med., Karolinska Institutet, and specialist nurse at the Astrid Lindgren Children’s Hospital Uwe Ewald Renée see above Flacking Dr. of Med. and lecturer at Högskolan Dalarna and senior research fellow at the University of Central Lancashire in the UK Elisabeth Olhager Dr. of Med., consultant and operations manager at Skåne University Healthcare Mireille Vanpée Dr. of Med. at Karolinska Institutet and consultant and Specialist Director of Studies at the Astrid Lindgren Children’s Hospital Inger Öhlund Dr. of Philosophy and paediatric dietician at Norrland University Hospital CARE OF CHILDREN WHO ARE BORN EXTREMELY PREMATURELY THE NATIONAL BOARD OF HEALTH AND WELFARE Appendix 1. Recommended nutritional intake Nutrient (kg/d)a Liquid (ml) Energy (kcal) Protein/aa (g) Carbohydrates (g) Glucose (mg/kg/min) Fat (g) DHA (mg) Arachidonic acid (mg) Na (mmol) P (mmol) Cl (mmol) Ca (mmol) P (mmol) Mg (mg) Fe (mg) Zn (mg) Cu (Mg) Se (Mg) Mn (Mg) I (Mg) Vit A (RE) (IE) Vit D (IE) Vit E (TE) (mg) Vit K (Mg) Vit C (mg) Thiamine B1 (Mg) Riboflavin B2 (Mg) Pyridoxine B6 (Mg) Niacin (NE) (mg) Pantethine (mg) Biotin (Mg) Folate (Mg) Vit B12 (Mg) Day 0b Day 4c EN full dosed TPN full dosee 80-100 130-160 135-200 135-180 50-60 105-125 115-135 90-115 2-2.4 3.5-4.5 4.0-4.5 3.5-4 7-10 11-16 9-15 13-17 5-7 9-12 1.0-1.5 4-6 5-8 3(-4) 12-60 11-60 18-45 14-45 0-1 2-4 3-7 3-7 0-1 1.0-2.5 2-3 2-3 0-1 2-4 3-7 3-7 0.5-1.5 2.2-2.7 3.0-3.5 1.5-2 0.5-1.5 1.7-2.5 2-3 1.5-1,9 0-4 6-11 8-15 4,3-7,2 0 2-3 0,1-0.2 1-1.5 1.5-2.5 0.4-0.45 70-110 120-200 20-25 2-5 2-7 2-5 0-4 1.0-7.5 0-1 10-30 10-50 10 1 000-2 300 1 300-3 300 700-1 500 220-600 400-1 000 40-160 2.2-7 2.2-11 2.8-3.5 4.4-20 4.4-28 4.4-16 13-35 11-46 15-25 140-300 140-300 200-350 150-300 200-400 150-200 45-250 45-300 150-200 0.4-7,0 0.4-5,5 4-7 0.3-2,0 0.3-2,1 1-2 1.7-12,0 1.7-16,5 5-8 35-90 35-100 35-80 0.1-0.6 0.1-0/77 0.1-0.5 Reference: [126-128] a Per kilo body weight and day for all units. The relevant weight is used for body weight except for the first few days when the birth weight is used until it has been achieved and passed. b Here, day 0 is defined as the date of the birth, i.e. from the birth until the morning of the next day. The recommendation applies to a full day and needs to be individually adjusted down depending on the time when the child is born c The child ought to be given a full dose of nutrition at least as of the fourth day of life (but still with some fluid restriction). The recommendation in this column is approximate and is based on 50 per cent enteral and 50 per cent parenteral nutrition. The exacta targets (which must be individually calculated) depend on the proportions of the parenteral supply of the nutrient in question, so the target will be slightly lower than stated if the 3 1 child receives a greater share of parenteral nutrition for example. d Recommended intake for full enteral nutrition (EN). e Recommended intake for total parenteral nutrition (TPN). 3 2 Appendix 2. Examples of pain assessment instruments Pain assessment instrument Reference Astrid Lindgren and Lund children's hospitals pain [185] ALPS-Neo and stress assessment scale for preterm and sick newborn infants Astrid Lindgren children's hospital pain ALPS 1 assessment scale for term neonates Behavioural Indicators of Infant Pain [186] [187] [188] NFCS E'chelle Douleur Inconfort Nouveaune Neonatal Facial Coding System NIPS Newborn Infant Pain Scale [191] N-PASS Neonatal Pain, Agitation, and Sedation Scale Premature Infant Pain Profile Premature Infant Pain ProfileRevised [192] BIIP COMFORTneo EDIN PIPP PIPP-R [189, 190] [193] [194] Dimensions Behaviour: facial expression, level of consciousness, activity and tone in extremities. Physiological: breathing Behaviour: facial expression, level of consciousness, activity and tone in extremities Physiological: breathing Behaviour: facial expression, hand activity, sleep Behaviour: facial expression, level of consciousness, movement and tone in extremities, crying Emphasis Continuous Procedure Continuous 23-32 weeks 24-43 weeks Behaviour: facial expression, body movements, quality of sleep, contact, consolability Behaviour: facial expression Continuous 34-37 weeks Continuous Procedure and Continuous Procedure Behaviour: facial expression, breathing patterns, extremity movements, level of consciousness, crying Behaviour: crying, level of consciousness, facial expression, extremity tone Procedure and Physiological: heart rate, breathing rate, blood pressure, oxygen saturation Continuous Behaviour: facial expression Procedure Physiological: heart rate, oxygen saturation Context: gestational age, level of consciousness CARE OF EXTREMELY PREMATURE INFANTS THE SWEDISH NATIONAL BOARD OF HEALTH AND WELFARE 33 Validated for gestational age < 42 weeks, cared for at a neonatal unit directly after the birth Full-term until one month old 23-40 weeks 24-48 weeks 3 4