Salisbury`s Bargain

advertisement

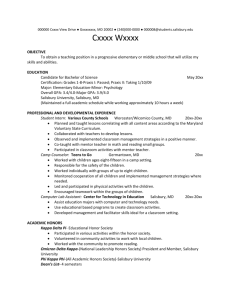

Cora Newsom 3/12/06 Dr. Strow Econ 467 Salisbury’s Bargain England, German East Africa and Germany June 1888 - July 1890 In the early summer of 1888, Lord Salisbury began discreetly entertaining notions of expanding British territory in Africa. He summoned Vice-Consul in the Niger delta Harry Johnston to the Foreign Office to explain his policy. Johnston was invited to Salisbury’s house party where they discussed Salisbury’s plans for extending the Empire. Salisbury hinted that the public should be informed of the whole African question by way of a newspaper article. Just weeks later The Times ran an article entitled “By An African Explorer,” leaking Lord Salisbury’s secrets. This article contained two proposals. “Cape-to-Cairo” was the plan to bridge the 3000mile gap between British South Africa and British-controlled Egypt. “Niger-to-the-Nile” was the plan to bridge the gap between North and West Africa. The “Cape-to-Cairo” plan wasn’t as vulnerable in Parliament because it didn’t require an exchange of territory. Originally, Salisbury agreed with Gladstone; British influence must be kept predominant in Egypt but that troops should be evacuated as soon as self-government was resumed. However, a negotiation with the Sultan at Constantinople fell through because France and Russia joined forces and threatened to invade the Ottoman Empire if the Sultan ratified the agreement. Salisbury was even more adamant at digging in at the Egyptian delta because “France is, and must always remain, England’s greatest danger.” Baring, stationed in Egypt, was also opposed to British withdrawal because he didn’t trust that the Khedive and his men could maintain a stable government and would be vulnerable to European exploit. External aggression also made British withdrawal from Cairo impossible. In addition, Baring thought it would be fatal for any 2 European power except Britain to control the upper Nile basin because, at the time, it was believed that Nile could be diverted from Egypt and thereby destroy its economy. Salisbury wanted to allow Baring and the British army to remain at Cairo and to reach the Equator, pushing 1400 miles, grabbing all territories on the White Nile to Lake Victoria. At the same time, Salisbury wanted to reach to the Equator from the south. Young diamond magnate Cecil Rhodes was pressing the British government for permission to push the power far to the north. Two things attracted the British government to Rhode’s scheme. He claimed to be “good for a million,” asking nothing from the British taxpayer; he just wanted a royal charter to establish the British South Africa Company. Also, his scheme complemented William Mackinnon’s; he had applied for a charter for British East Africa. The “Cape-to-Cairo” idea was being entertained as a way of meeting Britain’s strategic imperatives at the Canal and at the Cape. Despite his suspicions of Mackinnon, Salisbury recommended that the Queen sign the royal charter giving political responsibilities and commercial rights to the new Imperial British East Africa Company (IBEAC). Mackinnon was an idealist and romantic who had answered Livingstone’s call to open up Africa. Kirk had first encouraged him to try to open up the whole coast of East Africa; he failed due to Salisbury’s lack of confidence and the Germans. Then Mackinnon embarked on the Emin Pasha relief expedition. His plans to bring the “3 Cs” to the new British sphere involved Stanley who was lost and presumed dead in the African interior. Even so, he continued successfully with his plans and launched the IBEAC. The issue was quickly a sell-out with much due to the list of directors including Sir John Kirk. In Mackinnon, Kirk saw the only hope extending British control over the whole of East Africa. The main question was how to proceed, either cautiously inland from Mombasa or to race the Germans for territory in Uganda and Equatoria. 3 In the early summer of 1888, there was news that a group of German colonialists had commissioned Carl Peters to lead a new expedition beyond the German sphere, its objective to found a new colony and to induce Emin to bring Equatoria into the Kaiser’s new empire in Africa. Upon hearing the approval of the IBEAC, George Mackenzie was chosen to set up company headquarters at Mombasa. He then arranged for a large caravan to proceed up-country, ultimately led by Frederick Jackson. Jackson was to buy safe passage from the Masai and then to press on to the Nile and link up with Emin. Jackson was instructed to exploit Emin’s wealth in ivory, not to bring him arms, though nothing had been heard from him in eighteen months. Eventually Stanley got a message to Kirk saying that Emin’s men had mutinied and that the Mahdists had invaded. Despite protests from some of the Company’s directors of this leading to bankruptcy, Mackinnon and Kirk decided that Salisbury couldn’t be trusted; Peters would take Uganda unless Jackson got there first. Then due to Peters’ reckless advance, the Europeans feared the Arabs would unite and take them all out. The leader of the first uprising against the British was Abushiri. The Germans had negotiated with the Sultan; the Sultan leased the administration of the southern coastal strip to the German Company in return for a percentage and for them to act in his name and under his flag. Instead of acting in the Sultan’s name, the Germans threatened to invade and capture the Sultan. The Sultan fled. Later when he didn’t confirm his authority, Abushiri emerged as a leader of a militant faction. Abushiri persuaded the people to defy the Sultan’s wishes and to raise all the coastal towns against the Germans. A wild army of 20,000 men hunted the German agents; most managed to flee to German outposts. Abushiri then tried to open up a new front and take down one of the outposts; another 1000 men led by Suleiman tried to take out another outpost. Both failed against superior firepower and discipline. Abushiri called a truce with a 4 German admiral and then launched another attack at the German headquarters. Finally Bismarck intervened with a naval blockade of the coast with the help of Lord Salisbury. The German East Africa Company’s charter was cancelled. And in part of the agreement with Salisbury, Peters was dismissed and ordered not to set foot on German territory. Kaiser Wilhelm I died, and ultimately his son Kaiser Wilhelm II who had always sided with the Bismarcks took the throne. The new Kaiser didn’t react well to not being listened to and developed a secret new policy of deposing Bismarck. Bismarck then tried to form a defensive alliance against France with Britain. Since Salisbury knew this was no longer in Britain’s best interests, Bismarck proposed a territory swap of German territory in Africa for British territory in Europe (Heligoland) that would aid Germany in the event of a Franco-German war. News was received that the rebels had been defeated, but Abushiri was still free. Also, Peters had broken the blockade and landed in East Africa carrying the German flag. Peters landed in Zanzibar, defied orders, and used tricks to make his way inland. By doing this Peters was left with a small army and no goods to trade for peaceful transit, so a policy of terror was adapted. They killed everyone in their way and burned the villages. Their guns made them invincible, so Peters made it through the Masai and on to Busoga. Finally the news of Emin abandoning Equatoria and retreating with his rival Stanley reached Peters. Then he found out that King Mwanga was in need of help. Offering the British a protectorate, Mwanga asked Stanley and Jackson fro aid, but both refused on the grounds that they were too weak to intervene in the civil war in Buganda. Peters was determined to rescue King Mwanga with his smaller army and try to establish a German protectorate over Buganda. Lord Salisbury resumed his negotiations with Germany for a settlement. The Chancellor of Exchequer was set against imperial expansion, thus the Treasury refused to dole out the 5 millions needed to extend British supremacy over South Africa. So Salisbury recommended the Queen sign Rhodes’ charter allowing him to prevent the Boers, Germans, and Portuguese from gaining control of that vital region. Salisbury then appointed Johnston to be HM Consul at Mozambique; Johnston was to explore the disputed area north of the Zambezi, plying the local chiefs with lavish presents and blank treaty forms. Again the Treasury couldn’t be persuaded to fund the extra expense, but Rhodes stepped in and wrote a check to cover the expense. Salisbury ran into problems when Bismarck was forced to sign a letter of resignation and vanished from the scene. Percy Anderson went to Berlin to take up negotiations with Bismarck’s successor. Terrifying Mackinnon, the Foreign Office in Berlin reneged on Bismarck’s assurance that Uganda and Equatoria were beyond the German sphere. Then Mackinnon found out that Emin had blown off the British and was heading for his old province of Equatoria on behalf of the Germans. Mackinnon also found out that after Peters helped put Mwanga back on the throne, the King had signed an agreement that gave Germany a protectorate over Uganda. Britain offered Heligoland and four huge demands. The Kaiser accepted with a couple of minor concessions from Salisbury. In total Britain exchanged three square miles of a European island for at least 100,000 square miles of Africa (Zanzibar, Uganda, and Equatoria). A month later Salisbury began to end the estrangement between Britain and France that began eight years earlier with Britain occupying Egypt. France was given their own “sphere of influence” -- several million square miles of the Sahara.