Documentation of Good Adaptation Strategies and Practices

advertisement

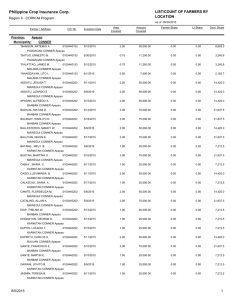

AWARENESS ON CLIMATE CHANGE AND ADAPTATION STRATEGIES OF VULNERABLE COMMUNITIES IN ISABELA, PHILIPPINES Eileen C. Bernardo Department of Environmental Science and Management College of Forestry and Environmental Management Isabela State University Cabagan, Isabela, Philippines ABSTRACT This study aimed to assess the awareness on climate change and adaptation strategies of vulnerable groups in the northern part of Isabela province in the Philippines. The data in this study were gathered from interviews with farmers residing in vulnerable areas in Northern Isabela. Results showed that the farmer respondents interviewed are aware of climate change issues and impacts. Most of them said that with the changing weather and climatic conditions, there are more frequent instances where their corn harvest has been affected. They also observed that there were more cold days about twenty to thirty years ago than in the recent years. In the past, the weather is predictable but recently, it is very unpredictable and that typhoons are becoming more frequent in Isabela. The adaptation strategies that are directly related to climate change as experienced by the farmers include the following: Use of multicropping or planting other crops in between cropping to increase soil quality; use of compost or organic fertilizer; changing the planting schedule; optimizing rice productivity with optimum use of fertilizers and other inputs; irrigation; planting drought-resistant varieties of corn; use of more disease-and-pest-tolerant crop varieties of rice; delay in planting until flood subsides; planting when there is still soil moisture, water harvesting, “forced” harvesting, and bayanihan among families. Results of the study showed that the respondents perform simple practices yet good local adaptation strategies to climate change. Key Words: climate change, awareness, adaptation strategies, vulnerable communities INTRODUCTION Climate change is a serious environmental challenge that could undermine the drive for sustainable development (The World Bank, 2008). Climate change is not only an environmental issue among others. It is by far the most serious environmental issue facing human kind. It is one of the biggest, social and economic threats that the world is currently experiencing. Climate change is presently a threat to development. Adaptive capacity of human systems is low and vulnerability is high in the developing countries of Asia including the Philippines. The Philippines is considered as one of the most vulnerable countries to climate change. With impacts ranging from extreme weather events and periodic inundation to droughts and food scarcity, climate change has been a constant reality that many Filipinos have had to face. Most affected are those living in coastal communities and the lower rung urban communities that lack awareness on proper disaster preparedness measures to take (http://wwf.org.ph/wwf3/climate/phils). Unlike other countries in the region, the Philippines is exposed to multiple hazards such as tropical cyclones, flood, landslides, and droughts. These natural hazards affect agricultural output. Since 34% of the country’s labor force is involved in agriculture, the livelihood of a large share of the population is at risk due to climate changes (Bordey et al, 2013). Based on the policy report of the Washington-based International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), Agriculture is extremely vulnerable to climate change. Higher temperatures eventually reduce yields of desirable crops while encouraging weed and pest proliferation. Changes in precipitation patterns increase the likelihood of short-run crop failures and long-run production declines. Climate change is more disastrous to the agricultural industry of the Philippines and its neighboring countries than in other parts of the world (Tacio, 2013). The country must act and respond now to the threats posed by climate change. According to the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MEA) published in 2006, climate change now poses one of the principal threats to the biological diversity of the planet, and is projected to become an increasingly important driver of change in the coming decades (CBD, 2007). Projections on climate change show that the global temperature is continuously increasing. Based on the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in 2001, the world average temperature will increase by 1.4 oC to 5.8oC between 1990 and 2100 if the current levels of emission are not reduced. This is mainly due to anthropogenic sources such as the use of fossil fuels especially in the developed countries. The Fourth Assessment Report of the IPCC (4AR 2007) observes that climate change is already happening. A further acceleration likely leads to a global temperature rise and related increase of extreme weather events. At the global level, human activities have caused and will continue to cause a loss in biodiversity. Changes in climate exert additional pressure and have already begun to affect biodiversity (IPCC, 2002). The potential impact of climate change on the world’s biological resources has become a priority and was most recently highlighted in relation to global food shortages, food price rises, and disease and vector transmission. The importance of climate change in biological diversity issues was further highlighted when the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) urged the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) to take all possible action to reduce the effects of climate change on ecosystems and natural resources. To deal with negative effects of climate change there are a number of adaptation strategies that can be adopted in different situations. Adaptation to climate change refers to adjustment in natural or human systems in response to actual or climatic stimuli or their effects, which moderates harm or exploits beneficial opportunities (IPCC, 2002). It is a process through which people reduce the adverse effects of climate on their health and well being and take advantage of the opportunities that environment provides (Chakeredza, 2009). Research studies on climate change adaptation have been done (Tiksay, 2008) and some of the adaptation strategies include the implementation of policies, and integration of policies in the major curricula in educational institutions. Other adaptation strategies include capacity-building to integrate climate change into sectoral development plans involving local communities in adaptation activities, and raising public awareness. This study aimed to assess the awareness on climate change of farmers in vulnerable barangays (villages) in the northern part of Isabela province, Philippines. It is also aimed to determine their climate change adaptation strategies and practices. METHODOLOGY Location of the Study This study was conducted in vulnerable barangays (villages) in the municipalities of Cabagan, Santo Tomas, Delfin Albano, San Pablo, and Santa Maria in Northern Isabela, Philippines. The villages are flood-prone areas. Gathering of Data The primary data in this documentation study were obtained through interviews with thirty six (36) farmer respondents using purposive sampling. There were 15 respondents from Cabagan, six (6) respondents from Santo Tomas and five (5) each from Delfin Albano, San Pablo and Santa Maria. The secondary data were obtained from the Provincial Planning and Development Office in Ilagan City, Isabela. Previous data in the study of Bernardo and Ramos (2009) obtained from the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA), Region 2, in Tuguegarao City, Cagayan and from the provincial office of the Department of Agriculture in Ilagan, Isabela were also utilized. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION Description of the Study Area The Philippines is composed of 7,107 islands 1,000 of which are inhabited. It has a total land area of 300,176 square kilometers, 47% of these is agricultural land. Twothirds of the population depends on agriculture for livelihood. One half of the labor force is engaged in agricultural activities. The Philippines has a forest cover of about 7M hectares and the coastal area is 36,289 kilometers, roughly equivalent to the Earth’s circumference. The coral cover is about 26,000 square kilometers, second largest coral cover in the world. The country consists of sixteen (16) regions. The regions are geographically combined into the three island groups of Luzon, Visayas, and Mindanao. A region is an administrative subdivision in the Philippines. Regions are generally organized to group provinces that have the same cultural and ethnological characteristics. The provinces are actually the primary political subdivision. They are grouped into regions for administrative convenience. The province of Isabela is strategically located right at the heart of the Cagayan Valley region (Region 2) in Northern Luzon. It has a total land area of 10,665.4 sq. km. Isabela is the second largest province in the Philippines. It is an agricultural province and is the rice and corn granary of Luzon due to its plain and rolling terrain. Isabela has a population of 1,401,495. Figure 1 shows the map of the Philippines and the province of Isabela. This study was conducted in the municipalities of Cabagan, Santo Tomas, Delfin Albano, San Pablo, and Santa Maria. These municipalities are located at the northern part of Isabela province. Cabagan is a first class municipality. Cabagan has a population of 48,350. It has a total land area of 430.4 square kilometers (43,040 hectares). It occupies about 2.43% of the land area of the province. It includes the Sierra Madre mountain range on the eastern and western parts of the municipality. Cabagan is subdivided into 26 barangays (villages). Cabagan is about 34 kilometers away from Tuguegarao City in the province of Cagayan, the regional center of Region 2, and about 50 kilometers away from Ilagan, the capital town of Isabela province. Cabagan is approximately 460 kilometers north of the City of Manila. Santo Tomas is a fourth class municipality. According to the 2012 census, Santo Tomas has a population of 22,172 in 3,854 households. It has a total land area of 150.0 square kilometers (15,000 hectares). Santo Tomas is politically subdivided into 27 barangays. Delfin Albano is a 4th class municipality in the province of Isabela. The municipality is formerly known as Magsaysay, Isabela. According to the 2012 census, it has a population of 24,899 people in 4,825 households. The Municipality of Delfin Albano is located at 38.0 kilometers northwest of Ilagan, the capital town of the Province of Isabela. Delfin Albano occupies a total land area of 189.0 square kilometers (18,900 hectares), which is further subdivided among the 29 barangays. The total land area contains varied land use, which were developed in response to population and economic growth of the total land area, to wit: agriculture (59.04%), built-up areas (2.74%), forest (4.74%), open grasslands (30.15), and road and water bodies (3.33%). San Pablo has a total land area of 63,790 hectares which is subdivided among 17 barangays. It has a population of 24,420 in 4,136 households. Santa Maria has a total land area of 14,000 hectares which is distributed to 20 barangays. It has a population of 20,695 in 3,280 household. Table 1 shows the List of municipalities and vulnerable barangays where the study was conducted, and the land area, population, and number of households. Climate Variability in the Cagayan Valley region The climate of Northern Isabela falls under two distinct types - Type III and Type IV. Type III is characterized by no pronounced maximum rain periods, dry season lasts from one to three months. The area is partly sheltered from the northeast monsoon and trade winds but open to the southwest monsoon or at least to frequent storms. Type IV, on the other hand, is characterized by the even distribution of rainfall throughout the year. The most common air currents in the country are northeast monsoon (from the higher pressure of Asia), the trade winds (from the Pacific), and the southeast monsoon (from the southern hemisphere). The general direction of the winds from these sources are from north to east (October to January) from the east to the southeast (February to April) and southerly (from May to September). Figure 2 shows the estimated corn production in metric tons per hectare of farmland planted with corn, and mean annual rainfall data. Figure 3 shows the estimated yield in metric tons per hectare of farmland planted with corn, and mean annual rainfall data. Based on Figs. 2 and 3, the highest mean annual rainfall was registered in 2005. It can be seen in Fig. 3 that the yield in 2005 is low. This confirms that one of the impacts of climate change is decrease in yield or low agricultural productivity. Low agricultural productivity will consequently affect food security and the health of the people. Figures 2 and 3 were taken from the paper of Bernardo and Ramos (2009) and on climate change adaptation strategies and practices by farming communities in Cabagan, Isabela. It is a part of the PATLEPAM (Philippine Association of Tertiary Level Educational Institutions for Environmental Protection and Management) - GIZ (Deutsche Gesellschaft fur International Zusammenarbeit) Project on Documentation of Good Adaptation Strategies and Practices to Climate Change by Selected Higher Education Institutions. Awareness of Farmers on Climate Change The farmer respondents were interviewed on climate change awareness. Most (83 percent) of those interviewed believe that there is cause for concern when it comes to climate change. According to 15 respondents, they have observed that with the changing weather and climatic conditions, there are more frequent instances where their corn harvests has been affected and decreased in yield. Three respondents, whose ages are 77, 72 and 68 years old, said that there were more cold days about twenty to thirty years ago than in the recent years. They also mentioned that in the past 50 years, they seldom experienced major calamities in the past but these days, they are frequently experiencing a lot of major calamities such as typhoons and flooding. They also observed that there are more pests now than in the past. Ten respondents mentioned that in the past, the weather is predictable but recently, it is very unpredictable and that typhoons are more frequent in Northern Isabela. One respondent commented that farmers need to learn to adapt to climate change. He suggested that technicians from the Department of Agriculture should disseminate information to the farmers the impacts of climate change. The respondents are knowledgeable of the following climate change topics: El Niño, La Niña, climate change adaptation, impacts of climate change and climate change risks. Adaptation Strategies of the Respondents Droughts and floods are a part of the Filipinos’ lives. Typhoons are hitting the country more frequently. In the Philippines, the sector most affected by climate change, so far, is agriculture and food security (Amadore, 2005). In this study, there were thirty (36) farmer respondents interviewed. Table 2 shows the local adaptation strategies of the farmer respondents. These farmer respondents include farm owners, tenants and farm laborers. In this study, the tenants are those that till the land of the farm owners while the farm laborers are those hired by the farm owners. In many cases, the farm owners also work as farm laborers in their own farms. Based on Table 2, seven farmers or 19% of the respondents mentioned that planting other crops in between crops is the strategy that they employ. These farmers plant mungbean and peanuts. The farmer respondents said that they practice this intercropping/multicropping strategy to improve the quality of the soil. Three farmers or 8% plant tobacco after the first cropping season. Five of the 36 farmer respondents or 14% mentioned the use of organic fertilizer and/or compost as a strategy. These farmers said that organic fertilizers are cheaper than inorganic, hence, more affordable. One of them said, he uses organic fertilizer to “reduce the negative reaction of soil to inorganic fertilizer and to improve the soil condition.” Another respondent uses organic fertilizer that is provided by the local government. The other farmer respondents do not use organic fertilizer because of the following reasons: non-availability of organic fertilizer in their area; it is difficult to apply, not popular among farmers, and crop yield is low. Four farmer respondents or 11% revealed that they have no fertilizer inputs in order to lessen the amount of money at risk. These poor farmers said that they do not want to take risks and therefore, will not use fertilizer at all. Four farmers or 11% altered application of nutrients/fertilizers. They never follow the recommended amount of fertilizer. Ten farmer respondents or 28% mentioned the following: Optimizing rice productivity and optimum use of fertilizers and other inputs. Twenty-seven farmers or 75% mentioned that adjusting the plant calendar is a good option. As explained by some of the respondents, they now change the planting schedule. As an example, many of the corn farmers explained that in the past, the planting season was in April and in October, however, in recent years, there is drought in April and typhoons hit the province in the months of October and November. In October 2009 and 2010, and in September 2011, two typhoons in each month and year, respectively, hit the province of Isabela. Recently, the farmers plant the first cropping in May and the second in either November or December. Others plant in June and in January. Fourteen corn farmers or 38% said they plant drought-resistant varieties of corn. Twelve farmers or 33% use more disease and pest-tolerant crop varieties. Seven farmers or 19% irrigate their farm using deep/pump wells. Ten farmers (28%) plant when there is still soil moisture. Nine respondents (25%) said that when there is a typhoon forecast, they harvest their crops immediately (“forced” harvesting). Twelve mentioned bayanihan among families. This is a Filipino tradition which shows the cooperative effort among family members during planting and harvesting seasons. Family members volunteer to help in planting and harvesting. The activities done by the farmers are simple practices, yet these are actually good adaptation strategies to climate change. Figures 4 shows rice fields in Villaluz, Delfin Albano and Fig. 5 shows a corn field in Cabagan, Isabela. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS Climate change is one of the biggest challenges the world is facing at the moment. In fact, many would consider it the most serious emergency the human race has ever faced (Mcdonagh, 2007). Farmers in Northern Isabela, Philippines are aware of climate change and they perform simple practices to minimize its effects yet these practices are good local adaptation strategies to climate change. There is an urgent need for an effective and sustained program to enhance the level of climate change awareness among policy/decision makers, the various stakeholders, the media, students and the academe, and the general public, for their own empowerment (Amadore, 2005). The Philippines has to intervene to minimize these risks and to prepare adaptive measures that would anticipate social and economic consequences which cannot be mitigated. Adaptation efforts must be prioritized in communities where vulnerabilities are highest and where the need for safety and resilience is greatest. The agriculture sector is vulnerable to climate change. Various agencies have climate change adaptation and mitigation programs. The challenge is for the Philippine government to consolidate these efforts and move in one direction so that the country will have a coherent and integrated policy and action framework to mitigate, and adapt to, climate change (www.doe.gov.ph/cc/c&c.htm) Adapting to climate change will entail adjustments and changes at every level – from community to national and even international. Communities must build their resilience, including adopting appropriate technologies while making the most of traditional knowledge, and diversifying their livelihoods to cope with current and future climate stress. Local adaptation strategies and traditional knowledge need to be used in synergy with local and government interventions. The choice of adaptation interventions depends on national circumstances. To enable workable and effective adaptation measures, governments, institutions and also non-government organizations, must consider integrating climate change in planning and budgeting in decision making (UNFCC, 2007). ACKNOWLEDGMENT The author would like to thank EEPSEA for the financial support to present the paper to the EEPSEA Conference on Economics of Climate Change in Siem Reap, Cambodia. References Amadore, Leoncio A. 2005. Crisis or Opportunity: Climate Change Impacts in the Philippines. Greenpeace. www.greenpeace.org/seaasia/en/asia-energy-revolution/ climate-change/ Philippines-climate-impacts. Bernardo, E. C. and M. T. Ramos. Documentation of adaptation strategies to climate change by corn farmers in Cabagan, Isabela. Poster Presentation. 6th CVPED International Conference on Environment and Development. June 1-5, 2009. Isabela State University, Cabagan, Isabela, Philippines. Bordey, F. H. 2013. Linking Climate Change, Rice Field and Migration: The Philippine Experience. Convention on Biological Diversity. 2007. CBD: Biodiversity and Climate Change. International Day for Biological Diversity. Accessed on line at www.biodiv.org Chakeredza, S. et al. 2009. Mainstreaming Climate Change into Agricultural Education: Challenges and Perspectives. African Network for Agriculture, Agroforestry and Natural Resources Education (ANAFE) and World Agroforestry Centre. Accessed on line at www. anafeafrica.org. IPCC (2001-WGI): Climate Change 2001: Synthesis Report, Working Group I Technical Summary, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Secretariat. IPCC. IPCC (2002-WGII): Climate Change and Biodiversity. Technical Paper V. Working Group II Technical Support Unit. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). April 2002. Accessed on line at www. IPCC. Climate Change 2007. Synthesis Report of Working Groups I, II and III to The Fourth Assessment Report. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Jabines, A. 2006. Philippines www.philippinestoday.net. Losses Billions to Climate Change. McDonagh, S. 2007. Climate Change: The Challenge to all of us. Claretian Publications. Quezon City, Philippines. Presidential Task Force on Climate Change. 2007. Climate Change: The Philippine Response. www.doe.gov.ph/cc/ccp.htm. The World Bank. 2008. Biodiversity, Climate Change, and Adaptation: Nature-Based Solutions from the World Bank Portfolio. Tacio, H. D. http://www.sunstar.com.ph/weekend-davao/2013/12/08/climate-changeimperils-agriculture-317651 Ticsay, M. V. and L. P. Arbolleda (Eds.) 2008. Realizing Challenges, Exploring Opportunities. Proc. of the Intl. Conference-Workshop on Biodiversity and Climate Change in Asia: Adaptation and Mitigation. 19-20 February 2008. Pasay City, Philippines. UNFCC. 2007. Climate Change: Impacts, Vulnerabilites and Adaptation in Developing Countries www.canada.com/technology/environment www.doe.gov.ph/cc/c&c.htm Table 1. List of municipalities and vulnerable barangays (village), their land area, population, and number of households (2012 Census) Municipality (No. of Barangay)/ Area Population No. of Vulnerable Barangays (Hectares) (2012) Households Delfin Albano (29) Calinaoan Sur Villaluz Santo Tomas (27) Amugauan Bagutari Cabagan (26) Balasig Pilig Abajo San Pablo (17) Auitan San Jose Santa Maria (20) Mozzozzin San Rafael 18,900 24,899 4,825 15,000 22,172 3,854 43,040 48,350 9,404 63,790 24,420 4,136 14,000 20,695 3,280 Table 2. Local adaptation strategies of the farmer respondents No. Local Adaptation Strategies Planting other crops such as mungbean and peanuts in between cropping (Intercropping/ multicropping) 2 Planting tobacco after the first cropping season (Crop rotation) 3 Use of organic fertilizer/compost 4 Altered application of nutrients /fertilizers 5 Not applying fertilizer at all 6 Optimizing rice productivity and optimum use of fertilizers and other inputs. 7 Changing the planting schedule 8 Planting droughtresistant varieties of corn. 9 Use of more disease and pesttolerant crop varieties 10 Irrigating the farm using deep wells/ pump wells 11 Planting when there is still soil moisture 12 Rainwater harvesting and storage 12 “Forced” harvesting 13 Bayanihan among families. n = number of respondents Cabagan n = 15 Municipalities Santo Delfin San Tomas Albano Pablo n=6 n=5 n=5 Santa Maria n=5 Tot al % 1 4 1 0 0 2 7 19 2 1 0 0 0 3 8 2 2 1 0 0 5 14 1 2 0 1 0 4 11 1 2 0 1 0 4 11 3 1 5 1 0 10 28 8 4 5 5 5 27 75 1 2 1 5 5 14 38 2 2 2 1 5 12 33 0 0 5 1 1 7 19 5 2 1 1 1 10 28 4 3 2 1 1 11 31 2 1 1 0 5 9 25 4 2 1 1 4 12 33 Figure 1. Maps of the Philippines and the province of Isabela 250 28.00 Rainfall 27.00 150 26.50 100 26.00 25.50 50 Temperature 27.50 200 Rainfall Temperature 25.00 24.50 19 93 19 94 19 95 19 96 19 97 19 98 19 99 20 00 20 01 20 02 20 03 20 04 20 05 20 06 20 07 0 Year Figure 2. Mean Annual Rainfall (mm) and Temperature (oC) data from 1993-2007 (Source: PAG-ASA, Tuguegarao City, Cagayan. Taken from Bernardo and Ramos, 2009) 4.5 190 4.0 170 3.5 150 130 3.0 110 2.5 90 2.0 70 Rainfall Estimated Production 1.5 19 93 19 94 19 95 19 96 19 97 19 98 19 99 20 00 20 01 20 02 20 03 20 04 20 05 20 06 20 07 50 Estimated Production (Tons/Ha) Ammount of Rainfall (Mm) 210 Year Figure 3. Estimated corn production in tons per hectare (Source: Bureau of Agricultural Statistics, Ilagan, Isabela. Taken from Bernardo and Ramos, 2009) Figure 4. Rice fields in barangay Villaluz in Delfin Albano, Isabela Figure 5. Corn fields in Cabagan, Isabela