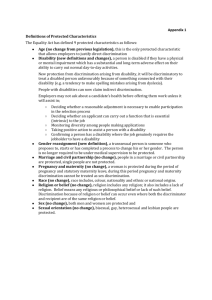

The law, judiciary and religion - Australian Human Rights Commission

advertisement