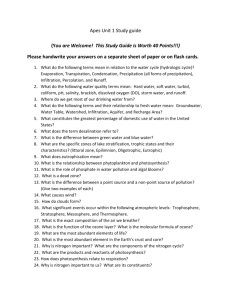

Sedimentation and Remote Sensing

advertisement

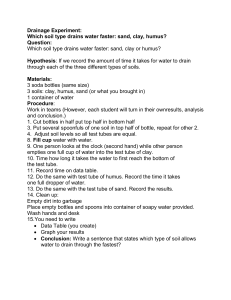

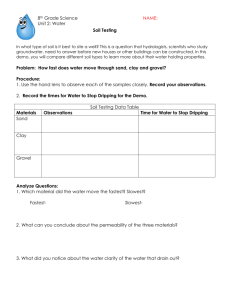

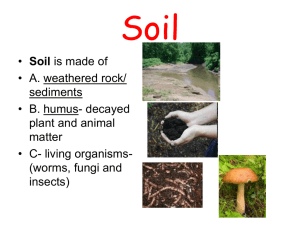

Sedimentation and Remote Sensing Introduction: A certain amount of released earth materials into water or the atmosphere is a natural occurrence; however, excessive sedimentation is of concern when environmental or commercial problems arise from the process. It is also of concern when the sedimentation is clearly the result of erosion, possibly due to urbanization, poor farming practices and industries such as mining. The tie to physical science is in the physics of soil processes such as infiltration, runoff and permeability. Infiltration is the rate of entry of precipitation into the surface of soil, runoff is the percentage of precipitation which does not enter the soil and permeability is the ease with which water can travel through the soil profile, usually measured as a rate as well. Infiltration rate is dependent upon several factors which are difficult to quantify, including soil type (textural), soil structure and slope. There is a dual nature to soil on a gradient and all of it is indeed “on a slippery slope.” If infiltration is not sufficient, runoff occurs and pulls soil particles with it in a steady stream. However, if infiltration is too great, massive earth movement called mudslides can occur. http://www.ent.iastate.edu/imagegal/practices/tillage/conventional/erosion.html U.S.G.S. Public Affairs Office, Menlo Park, CA. U.S.G.S Public Affairs Office Menlo Park, California Infiltration rate is lowest for clay particles in a massive structure on a steep slope. Clay profiles are characterized by a larger volume of pore space than sand, but all pores are much smaller than those for sand. Movement through the soil is not due to a gravitational gradient (as in sand) but is due to electrostatic attraction between hydrogen in water and electronegative elements in the soil (oxygen, silicon, etc.) The overall process is slow and there is usually not sufficient time for absorption due to rapid water flow on a steep grade unless there is sufficient vegetation to trap water for a longer time period. Clay or sand are soil textures; soil structure consists of a secondary organization of soil particles into “shapes” such as granular, cubic, columnar or one large mass (massive). The advantage of cubic or columnar shapes for infiltration is that channels exist in the soil which are larger than the individual pores and allow more rapid infiltration. http://nesoil.com/gloss.htm blocky structure of subsoil http://www.evsc.virginia.edu/~alm7d/soils/images/images1.html There are various equations for fluid flux through a permeable material; Darcy’s law is probably best known: q = -k (Pb – Pa)/ where q is fluid flux, k is permeability, Pb is pressure at base of fluid front, Pa is pressure at fluid head and is viscosity of the fluid. Flux is measured as m3/m2/s, which reduces to m/s. There are other equations which consider additional criteria, but all are dependent on permeability. One equation for hydraulic conductivity, which is similar to Darcy’s is: K = k / where K is hydraulic conductivity, k is permeability, is specific weight of water, and is viscosity of water. For “standard” conditions, hydraulic conductivity is very close to permeability. Hydraulic conductivity technically can vary with conditions of flow while permeability is a property of the soil itself. Permeability can be calculated with an equation: k = C d2 where k is permeability, C is a configuration constant and d is average pore diameter. Configuration constants can be estimated from texture and structure, but usually permeability is best measured empirically. Table 1. Size limits (diameter in millimeters) of soil separates in the USDA soil textural classification system. Name of soil separate Diameter limits (mm) Very coarse sand* 2.00 - 1.00 Coarse sand 1.00 - 0.50 Medium sand 0.50 - 0.25 Fine sand 0.25 - 0.10 Very fine sand 0.10 - 0.05 Silt 0.05 - 0.002 Clay less than 0.002 * Note that the sand separate is split into five sizes (very coarse sand, coarse sand, etc.). The size range for sands, considered broadly, comprises the entire range from very coarse sand to very fine sand, i.e., 2.00-0.05 mm. edis.ifas.ufl.edu/SS169 We are going to equate infiltration with permeability although they are technically different. Infiltration is dependent on permeability but also soil surface conditions. Permeability is typically measured under saturated flow conditions, which we will emulate in the laboratory, but infiltration rate can vary widely due to incoming rate of water. In the following laboratory, we will measure permeability for two soils- a clay and a sand- and look at permeability for these soils on a slope. Laboratory procedure: 1. Set up a canister with holes on the bottom, lined with filter paper (thin) and fill with sand about the one-fourth of the canister height. 2. Position the canister on a ringstand or other upright apparatus and clamp a hose or buret above the canister. A ring with a wire gauze between the hose and soil will help disperse the water over the soil. 3. Place another empty canister (without holes) below the soil canister (diagram A). 4. Slowly saturate the soil, then one student must adjust the faucet or buret flow until the rate produces ponding water and then back off to a flow where no ponding occurs. 5. Measure the leached water height in cm after about ten minutes and then divide this value by 10 to get permeability flow rate in cm/min. 6. For soil on a slope: Remember the faucet speed used in setup A and use this in setup B. The only difference here is that the soil canister will be put on a slope of about 10 degrees. 7. Repeat the same procedure as for setup A (at the same flow rate) and collect leached water in the lower canister for 10 minutes. Calculate permeability in cm/min. 8. Note rate of runoff as well. After 10 minutes, collect the water accumulated on the downward side of the surface with a pipet and place this into a canister of the same size as the others and note height in cm. Divide this by 10 to get runoff rate in cm/min. (If there is no runoff, increase the steepness of the soil until there is runoff and run the experiment again with measurements. Note the angle of inclination in your notebook.) 9. Repeat the entire process for a clay soil. If there is time, repeat the process for clay with plants “planted” in the soil. A slightly loose hose dispersed water well. A buret was somewhat more precise in pinpointing necessary flow rate. Using a protractor to measure slope Questions: 1. List permeability for the following: Sand, flat: 0.1 cm/min Pipetting runoff from soil at 10-degree incline Sand, tilted: 0.06 cm/min Clay, flat: 0.02 cm/min Clay, tilted: 0.005 cm/min Clay, tilted, with vegetation: 2. The rate of flow for the flat soils actually represents infiltration rate which is just below the ponding rate. Any type of ponding is considered to be potential runoff and erosive even when on a “flat” surface, due to imperfections in terrain. Which soil tolerated a higher rate of “precipitation” without ponding? sand 3. For the same angle, which type of soil produced more runoff, sand or clay? clay 4. What was the nature of the runoff water? (Did it contain soil, etc.) Contained small particles of soil 5. See if the following relationship tentatively worked out in class is a good predictor of runoff rate in cm/min: sinx(permeability rate on 0-degree slope) Where: is the angle of slope for the canister Permeability is the rate at 0-degree slope in cm/min For sand at no slope, permeability was 0.1 cm/min Calculated runoff for sand at 10-degree slope: Sin(10) x 0.1 = 0.017 cm/min Actual runoff rate for sand at 10-degree slope: 0.016 cm/min 6. a. Determine the gravitational acceleration on a discrete particle of water at the top of a slope which is 14.7 m long at an inclination of 20 degrees. a. Determine the velocity of this particle of water at the bottom of the incline. b. How much time will it take the water to reach the bottom of the slope? 7. a. For a sphere of water of 0.0042 cm3, calculate its mass and gravitational force it possesses on this slope. 0.0042 g; F = 0.0042 x 3.35 = 0.014 N a. The sphere of water will only be able to move a soil sphere of equal size or smaller (due to contact). Assume a coefficient of friction for the soil sphere of 0.9 and a density of 2.65 g/cm3. What is the radius of the largest sphere the water will move? What classification is it? (sand, silt, clay). Assume the gravitational force Fp of the water on this slope is translated into the lesser horizontal force Fh = Fp (cos 20) once it reaches the bottom: Fp = 0.014 N Fh = 0.013 N Assume Fh is equal to frictional force Ff to produce movement of constant velocity (not acceleration). This corresponds to the largest soil particle which can be moved. Ff= Fn 0.013 = 0.9Fn where Fn is the weight of the soil particle Fn = 0.0144 N The mass of the particle = 0.0144 N/9.8 = 0.00147 g 2.65 g/cm3 = 0.00147 g/x x = 0.000556 cm3 Vol of sphere = 0.000556 = 4/3 r3 r = 5.1 x 10-2 cm; Medium sand Relating sedimentation to remote sensing: Sedimentation can benefit agriculture by depositing nutrients on flood plains and extending delta land, but also costs humans in terms of flood damage, waterway clogging, poor water quality, and recreational site damage. Of late it is of increased concern due to effects on environments which are fragile: estuaries, wetlands, coral reefs and continental shelves. Erosion is increased soil loss and sedimentation due to poor supervision of human activities. The main causes of erosion include lack of vegetation on agricultural land, overgrazing, deforestation and mining operations. View the following satellite images and see if you can identify the location and find the sedimentation source: Image of the Ganges River delta and the Bay of Bengal acquired by the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS). This image shows the massive amount of sediments delivered to the Bay of Bengal by the Ganges River, sediments that are derived from erosion of the Himalayan mountain range to the north. Click on this image to see a large high-resolution version that includes the Himalayan range. Mt. Everest, the highest point in the world, is located in the upper right corner of the high-resolution image. http://daac.gsfc.nasa.gov/oceancolor/scifocus/oceanColor/sedimentia.shtml SeaWiFS image of the U.S. East Coast acquired one week after the passage of Hurricane Floyd (see image below). The sediments generated by the flood waters of rivers in North Carolina are seen entering the Gulf Stream off of Cape Hatteras. Also note the increased turbidity in the sounds and river estuaries and persistent sediment suspension southward along the coast. http://daac.gsfc.nasa.gov/oceancolor/scifocus/oceanColor/sedimentia.shtml SeaWiFS image of Italy and the Adriatic Sea. The Balkans to the west and the snow-covered Alps to the north are also visible. The Po River valley is the hazy brown area just south of the Alps. The plume of sediments carried by the Po River is seen on the western side of the far northern Adriatic Sea. http://daac.gsfc.nasa.gov/oceancolor/scifocus/oceanColor/sedimentia.shtml A large sediment plume enters the Mozambique Channel south of the resort town of Beira. (Satellite photo courtesy NASA) http://www.star.le.ac.uk/edu/Probes.shtml Conjectured water channels on the red planet. Here are a few interesting pictures of wind erosion as well: See if you can identify the location and the extent of wind-blown debris. http://www.msmedia.homestead.com Assignment: 1. Find erosion statistics for North Dakota: How much soil is lost per year by water erosion and by wind erosion? What is the tolerable limit set forth by the USDA? Source: USDA-NRCS Most sources list 5 tons/acre per year as the tolerable limit. 2. Find satellite images of sedimentation in rivers in the Midwest (North Dakota if possible.) The 1997 Red River flood might be a good case study, if satellite images are available. The following images show Red River flooding in 1997; although only water levels are shown, the amount of sedimentation from the event can be surmised. March 1997 before flood Red is snow cover; yellow is cloud cover April 1997 during flood May 1997 after flood www.math.montana.edu/.../rrf/flood_pics.html