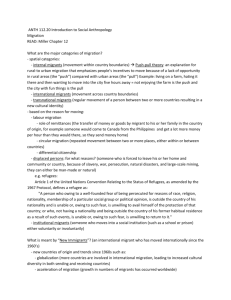

Full Text (Final Version , 618kb)

advertisement