Urban spatial development in Jerusalem after 1967

advertisement

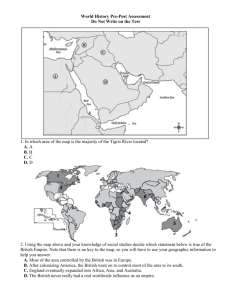

Geographic and Demographic in Jerusalem: General Look Rassem Khamaisi Jerusalem emerged from the old city which located in the top of the Al- Thuhoor hill overlooking the village of Silwan to the south-east of the Haram Al- Sharif . The old city is surrounded by the three valleys and this facilitates the task of defending it. The hill on which old Jerusalem was built represent the center of the Jerusalem mountains located in the middle of Palestine and which stretches from Marj Ibn Amen in the north to the Negave desert in the south. Jerusalem is located in the middle of this chain of mountains, at an altitude of 720-830 meters above the sea level. Jerusalem was a historical passage for convoys traveling between the African, European and Asian civilization. The central location give Jerusalem a unique status and made it a coveted place to in, as far back as the Stone Age which extends to about 12000 BC. This geographic location has an implication over the spatial development and expansion of Jerusalem. The geographic layout of any area is characterized by the topographic structure which include mountains, valleys and geological breaks, as well as result of human intervention through construction and destruction processes. Hence, the natural geographic layout of Jerusalem has affected its development, population distribution and economic activities. Most of the urban growth of Jerusalem between 139-1850 AD was concentrated inside the Old City walls. The Old City area underwent a process of demolition and reconstruction, therefore, it is comprised of layers of buildings that have been constructed and demolished as a result of natural causes like the earthquakes of 747 AD and 1066 AD or wars like those between 1077-1260 AD (Mustafa 1997, Cohen 1977).This development accelerated the population growth and made it impossible to confine urban expansion within the Old City walls. In 1872 the population of Jerusalem District was estimated at 58,000 residents but in 1922 it increased to about 148,000. Moreover, in 1872 the population of Jerusalem proper was estimated at 14,300 residents but in 1922 it increased to about 62,600 (Mustafa 1997). In order to absorb this growth of both the Arab and Jewish populations of Jerusalem it was necessary to establish new neighborhoods outside the walls. During the period between 1922 and 1947, the population of Jerusalem rose from 62,000 to 164,000, which actually means an increase of 165%. Jews increased by 192% during the same period while Arabs increased by 132%. for further details, see the following table: Table 1 : Population growth in Jerusalem between 1922 - 1947 2211 Year 2291 Arabs Jews Total % Arabs Jews Total % 2,6,61 96,,2 116191 ,951 ,,6,66 16966 ,,6666 1252 226926 116,,1 ,26119 ,951 ,26966 216666 2116966 1152 1126211 ,,6212 ,16616 266 Total -----9652 1,59 ,951 %of New City Source: Aref Al-Aref, 1961; Al-Dabagh, 1988. ,96266 226966 2,96966 266 9159 215, 1152 ------ National Group Old City New City According to the table, it is noticed that the new city formed 78% of the total population in Jerusalem in 1947. Moreover, most of the Jewish residents (97.6%) lived in the new city (Ben Areeh, 1990). This increase in population was accompanied by an increase in the number of houses, where houses increased from 21,403 homes in 1931, including 5,853 houses in the Old City to 40,000 homes in 1947 which were spread out over the 51% of the Jerusalem Municipality area at that time (Mustafa, 1997). Regarding the spatial distribution of the population, Jews were concentrated in the western part of Jerusalem, around the center of Jaffa road. As for Arabs, they were concentrated in the Old City and around it from all sides. The eastern region, which included al-Masharef mountain and the Mt. of Olives, was almost vacant. It should be noted that the spatial separation of population in Jerusalem on a national basis was the main platform for proposing ideas for dividing Jerusalem, similar to the proposal of dividing Jerusalem in 1945 by Sir W. Fitzgerald. As for the commercial center of Jerusalem, it was divided between the Old City and Jaffa Gate and New Gate towards Jaffa road until the Mahane Yehuda region, in addition to some small commercial centers distributed among the neighborhoods. During this period, industrial development was limited, therefore small craft workshops were distributed, part in the Old City and others in the New City. The spatial expansion and urban centralization in the city of Jerusalem coincided with the struggle between Arabs and Jews during the British Mandate. The struggle included control over local institutions, land ownership and urban expansion. The British control over the central administration contributed to offering Jews priorities in development. They were assisted and provided all necessary facilitation to find housing in Jerusalem as in other places in Palestine. The struggle an had impact on the emergence of separate ethnic residential quarters. The development of Jews towards the west was due to the following reasons: -2The moderate topographical structure which allows expansion without encountering any physical impediments. -1The connections Jews had with other Jewish areas in Palestine, such as Tel Aviv, Haifa and Tiberias. -,Transportation roads that connect Jerusalem with other developed centers in the west. -9Vacant areas where lands could be owned. Therefore, the spatial expansion in Jerusalem during that period was deeply rooted around and to west of the Nablus, Jerusalem and Bethlehem roads and especially around Jaffa road. As Jerusalem started to expand, the surrounding villages began expanding and developing to be connected later with Jerusalem. During that period, imported spatial samples began entering into Jerusalem’s urban space as part of the European and Jewish intrusion of Jerusalem. These samples started with concrete buildings during the period between 1850 - 1917 and increased to a point where they dominated over Jerusalem buildings. At the same time, urban and construction development started to be conducted according to the structural schemes and building constraints which included even in the Old City. The constraints stipulated that it was forbidden to build on a space of 2,500 meters from Damascus Gate without proper licensing. These planning constraints had an impact on the spread of buildings in Jerusalem and on the spread of new quarters according to the Garden City model. Due to the increase in population and the economic growth, especially among refugees, commercial centers began to emerge outside the Old City walls. At one point, the Old City was the center of economic, housing and administrative life in Jerusalem. Now however, the Old City has become a part or a quarter of the many quarters in the new Jerusalem which started to grow as a residential and administrative city. Attempts were made to renovate some of the important sites in it, such as Damascus Gate and the Citadel. The new city formed an economic administrative center for foreign communities in particular, while the Palestinian elite followed or accompanied the development of their residential sites according to the western models. As for the Old City, it kept its central role in housing the Arab residents as the most important residential, economic, cultural, religious and political center. The status of the Old City was considered as synonymous with the development of the Palestinian quarters, north and west of the Old City, such as al-Talbiyye and al-Baq’a Quarters, the German Quarter, the Greek Quarter, Herods Gate, Sheikh Jarrah and Wadi alJoz. Despite the rising competition between the Old City and the new city, the central status in terms of the housing, functional and administrative aspects was granted to the new city at the expense of the old, especially in terms of the constraints facing the expansion of the old city. This however, did not cause the Old City to lose its significance and importance. On the contrary, it remained the compass for planning and developing Jerusalem despite the selective immigration of the middle and upper classes to the new city. This situation contributed in the deterioration of its social, physical and economic conditions. Despite this, villages around Jerusalem were expanded until they became part of the city, especially from the southern side, such as the villages of Silwan and al-Thori. Urban spatial development in Jerusalem after 1967 Israel occupied the eastern sector of Jerusalem during the 1967 war including its West Bank tributary. This occupation / annexation caused the transformation of the divided city, between 1948 - 1967 into an open one. Israel announced its annexation and sovereignty over East Jerusalem and applied the Israeli law to it. The area which was annexed to Israel did not include only the areas which were part of the East Jerusalem Municipality (6,000 dunums), but covered approximately 70,000 dunums. This area was annexed to the sovereign area of the West Jerusalem Municipality which included around 108 dunums in 1968. It was later expanded to reach around 123,000 dunums (Choshen and Shahar, 1997). This administrative and spatial expansion was a basis for Israeli and Palestinian urban expansion in Jerusalem since the area of expansion included Palestinian villages such as Beit Haninah, Sur Baher, Isawieh, Kufur Aqab were not within the boundaries of Jerusalem. However, the Israeli government’s desire to create a reserve of vacant lands for Israeli architectural expansion inside Jerusalem was the main reason behind the annexation of these villages to its lands. Thus, expanding the new city was for strategic - demographic considerations (Kroyanker,1988). The considerations have guaranteed Israel’s total sovereignty over Jerusalem and rescuing it from the “siege” which it was under prior to 1967. This was achieved through: 1. Setting a political demographic formula which seeks to maintain the number of Palestinians in Jerusalem at less than 30% of the entire population of Jerusalem. 2. Guaranteeing the political and administrative centralization of Jerusalem through transferring and concentrating all administrative and government institutions in Jerusalem including East Jerusalem. The “government village” was established beside the Hyatt Regency which strengthened the connection between the Jewish quarters of western Jerusalem and the Hebrew University on the Masharef mountain and at the same time breaking the continuation of Arab development on the Nablus - Jerusalem axis. 3. Establishing a belt of Israeli settlements on the outskirts of the borders of the expanded Jerusalem to form support and nurturing for the heart of Jerusalem. The belt was established on two phases: the first through building quarters such as the French hill, Ramat Ashkol and Givat Hamiftar and later, establishing a belt on the outskirts such as Ramot Nevi Yacoub, Gilo and Ramot and also constructing a belt of settlements outside the city of Jerusalem which included the settlements of Ma’le Adumim, Pisgat Ze’ev, Avir Yacoub, Gosh Etzion.. etc. 4. Reinforcing and deep-rooting this settlement belt by connecting them by convenient roads and guaranteeing its urban continuation while cutting off Palestinian architectural expansion at the same time. 5. Deep-rooting the Jewish presence in the Old City through demolishing and evicting the residents of al-Magharbeh and al-Sharaf quarters, establishing new Israeli buildings, and housing Jews instead of Palestinians. This is in addition to confiscating and buying residential buildings inside the Muslim quarter of Jerusalem by using underhanded and fabricated methods in order to penetrate the Old City and assume control over it. 6. Israeli expansion in different directions in Jerusalem and increasing the Jewish population in Jerusalem to reach 421.2 thousand Jews in 1996, constituting 9.2% of the Jewish population in Israel. Thus, Jerusalem was transformed into the biggest city in Israel. 7. Limiting and cutting off Palestinian architectural expansion so it may not constitute an urban ethnic unit, and to insure that the percentage of Palestinians in Jerusalem is less than 30% of the population of Jerusalem (180.9 thousands of Arabs in 1996). Israel taking power into its own hands and exploiting its strength and control to create a new urban reality in Jerusalem was one characteristic in this epoch. Israel confiscated Arab lands in the area which it annexed after 1967. This area was approximately 25,000 dunums and some 15 new neighborhoods were established on which Jews only could reside. In 1993, the number of apartments in these neighborhoods was estimated at 45,000. Despite this, the urban structure of Jerusalem is still divided to Palestinian quarters or sections and other Israeli sections. The Palestinian rejection to be subjected to Israeli control led to the formation of dual or bilateral functional commercial centers. These centers served to increase of the population of Jerusalem which increased by 122% as the following table demonstrates:Table No. 2: the increase of Arab population in Jerusalem between 1967 and 1996 according to the population groups (thousands). Year 1967 1996 Rate of increase Arabs 68.9 180.9 163 Jews 197.7 421.2 113 Total 266.3 622.1 126 Source: Choshen & Shahar, 1998. It is clear from the table that throughout 29 years, the population of Jerusalem was increased by one and one-fifth times, while the number of Arab Palestinians increased by one and three- fifths. This reality led to the creation of an urban vocational structure characterized by the following points:1. The expansion of the city according to the model of a central city with a central historic heart and residential outskirts which include secondary centers. 2. Urban continuation which starts from Bethlehem and ends in Ramallah on the north-south axis of the city, starting from Lifta and Deir Yassin to the west until the Khan al-Ahmar region to the east. This urban extension covers around 60,000 dunums with different densities and with various usage of land. Map No. 4: division of Jerusalem quarters according to ethnic structure in 1997 inside the municipality borders of the expanded Jerusalem. 3. Models of buildings and various styles of quarters in terms of structure, density and height. There is a clear discrepancy between the Israeli and Palestinian quarters since the Israeli quarters were established by a governmental initiative whereas Palestinian quarters creepingly expand depending on private initiatives. According to the available data on utilized lands in Jerusalem, 60% of the influential area of Jerusalem is utilized. The following is a table which demonstrates the division utilized lands which form the urban spatial structure of Jerusalem. Table No. 3: utilization division for land usage in Jerusalem in 1995 according to the Israeli definition of the Jerusalem municipality borders Usage Housing Industry & handicrafts Institutions Usage of joint lands Hotels and tourism Public gardens & parks Private usage Total (lands) utilized Open and agricultural areas Total sum Area in dunums 42,804 4,059 5,166 2,583 738 16,113 3,813 75,276 47,724 123,000 % 34.8 3.3 4.2 2.1 0.6 13.1 3.1 61.2 38.8 100 Graph No. 1: division of the utilization of lands in Jerusalem according to the Israeli definition of the Jerusalem municipality borders Land use distribution in Jerusalem* (Percentages) Joint land usage 2 Agricultural and open 38 Housing 37 Private usage 3 Institutions 4 Open and agricultural 38 Public gardens and par 13 Hotels and public park 3 *according to the definition of Israeli municipal boundaries It can be noted from the table and graph that there are still vacant areas which equal half of the sovereign area within the Jerusalem borders. It was possible for some areas to be developed while others were left as green areas. This division of the urban structure of Jerusalem concentrates on the total current division of lands of which one-third of the area of Jerusalem is currently being used for housing while two-fifths of the city’s area remains undeveloped. These areas include agricultural areas, valleys and wild areas. As for the division of usage of land in East Jerusalem which was annexed to the Jerusalem municipality in 1967 and whose area covers 70,400 dunums, 37,348 dunums were outside the zoning area, and approximately 23,548 dunums were confiscated to establish Jewish quarters on it. The remaining 9,504 dunums were allocated for Arab construction, constituting only 13.5%. This period of urban development in Jerusalem was characterized by quick and directed development in order to create an urban, political and demographic reality which would ensure Israeli sovereignty and Palestinian subordination. This urban reality was created on the basis of action and reaction and not according to logical planning, which guides and is directed to the needs of the population. Both sides struggled for existence in Jerusalem. However, the difference was that the Israelis struggled for existence, although that they possess the power, resources and control. In this way, they initiated in developing the urban space to struggle for existence and maintain control over the future of Jerusalem whereas Palestinians do not possess the power or control. Therefore their struggle for existence depended on reactions and was on a short term basis to confront Israeli control. There is no doubt that the presence of financial resources and the economic growth between Palestinians and Israelis contributed to the growth of Jerusalem. Both grew and were brought up in Jerusalem despite the struggle and competition which accompanied this development and urban extension. In Jerusalem There are a three social and national groups which have a different demographic structure and spatial distribution: Palestinian, Secular Israeli and Orthodex Israeli. This different come as a result of natural increase rate which high beside the Palestinian 33 per 1000 in 1996, while among the Jews the comparable figure is 21 per 1000 in Jerusalem. The population growth in Jerusalem and the villages and towns which surrounding Jerusalem, create an urban spatial which extant from Ramalla in the north to Bet Lehem in the south which began to functional as metropolitan area that suffer from demographic and geographic structure different that base on the national belonging, which the next article will elaborate and analyse. BIBLIOGRAPHY: Dabbagh, M. (1988), Encyclopedia of our Homeland, Palestine, Dar al-Hadi, Kufr Qare’. Aref, A. (1961), The Particulars of the History of Jerusalem, al-Ma’aref printers, first edition, Jerusalem. Ben Arieh, Y. (1990), The Old and New City in the 19th Century, in Cohen, I. (Edited), Jerusalem, Studies in History of Jerusalem, Yad Yitzhaq Ben Tsvi - Jerusalem. Drouri, I. (1990), Jerusalem in the Mamluk Period, Cohen, A. (Edited), Jerusalem, Studies in History of the City, Yad Yitshaq Ben Tsvi, Jerusalem, pp. 102 - 105. Cohen, A. (1990), Jerusalem; Studies in the History of the City, Yad Yitshaq Ben Tsvi, Jerusalem. Kroyonger, D. (1988), Jerusalem - The Struggle over the City’s Structure and Characteristics, issued by Cater and Jerusalem Institute for Israel’s Research, Tel Aviv. Mustafa, W. (1997), Jerusalem, Population and Architecture, Jerusalem Media and Communications Center, Jerusalem.