Public Protests, Private Contracts: Confidentiality In ICSID Arbitration

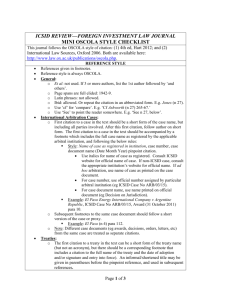

advertisement